Pd Nanoparticles in Functionalized Ionic Liquid supported in SiO2: Evaluation in Hydrogenation Reactions

Maicon R. Borges, Carla W. Scheeren*

Affiliation

Laboratory of Catalysis, School of Chemistry and Food, Universidad Federal do Rio Grande - FURG, Rua Barão do Caí, 125, CEP 95500-000, Santo Antônio da Patrulha, RS, Brazil

Corresponding Author

Carla W. Scheeren, Laboratory of Catalysis, School of Chemistry and Food, Universidad Federal do Rio Grande - FURG, Rua Barão do Caí, 125, CEP 95500-000, Santo Antônio da Patrulha, RS, Brazil, E-mail: carlascheeren@gmail.com

Citation

Carla W. Scheeren., Maicon R. Borges. Pd Nanoparticles in Functionalized Ionic Liquid supported in SiO2: Evaluation in Hydrogenation Reactions. (2018) J Nanotechnol Material Sci 5(1): 23-29.

Copy rights

© 2018 Carla W. Scheeren. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Nanoparticles, Ionic Liquid, sol-gel method

Abstract

The sol-gel method has been applied for supporting Pd nanoparticles (ca.4.8nm) previously synthesized in functionalized ionic liquids 1-n-butyl-3-(3-trimethoxysilylpropyl) imidazolium hexafluorophosphate [PMI.Si.(OMe)3.PF6] and 1-n-butyl-3-(3-trimethoxysilylpropyl) imidazolium bis (trifluorometanosul) imidato [PMI.Si.(OMe)3.N(Tf)2]. The results obtained by the catalyst formed (Pd/IL/SiO2), using acid or base medium was evaluated, as well as the texture of the support material, the activity and recycle. The catalyst Pd/IL/SiO2 synthesized in acidic conditions showed larger pore diameters, which in turn might be responsible for the higher catalytic activity in hydrogenation reactions studied.

Introduction

Palladium catalysts in solid supports are used in various industrial processes including hydrogenation, naphtha reforming, oxidation, automotive exhaust catalysts, and fuel cells[1-13]. The greatest advantages of using the SiO2 is due to its resistance to reduction and has low surface acidity, generating Pd/SiO2 an ideal starting point for study of the catalytic role of Pd[14-17].

The development of heterogeneous palladium catalysts proved to be an interesting promising for several reasons including simple handling, easy recovery and efficient recycling. Therefore, the development of highly active and recyclable heterogeneous palladium catalysts has become an important issue for the research of nanomaterials[18-20]. Recent attempts to develop highly efficient and recyclable Pd catalysts for the Heck, Suzuki and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation reactions, have been mainly focused on the utilization of polymers, alumina, carbon and silica-based support materials[21-25].

The application of an ionic liθuid with a solid support material is an alternative for the supporting of transition metal catalyst[26,27]. Thepre-organized structures of the imidazolium ionic liθuids (ILs) induce structural directionality[28-30]. The ionic liθuids are adaptable with other molecules due to the strong interaction of the hydrogen bonds, thus being an interesting material for the preparation of nanostructured materials[31-35]. According to the literature metallic nanoparticles of small diameter and narrow range of diameter distribution can be synthesized by reduction or decomposition of organometallic species dissolved in ionic liθuids[36,37]. The nanoparticles may be prepared by combining with other stabilizers or being transferred to other carriers in order to avoid agglomeration and generate more stable and active materials[31-35].

We present herein our results which show that palladium nanoparticles synthesized in functionalized ionic liθuid [PMI.Si.(OMe)3.PF6] and [PMI.Si.(OMe)3.N(Tf)2], can be used for the generation of the heterogeneous catalyst (Pd/IL/SiO2) viasol–gel processes. The heterogeneouscatalyst formed (Pd/IL/SiO2) was applied in hydrogenation reactions.

Experimental

General

All experiments were performed in air, except for the synthesis of the Pd NPs. The Pd NPs36 and the halide-free functionalized ionic liθuids [PMI.Si.(OMe)3.PF6] and [PMI.Si.(OMe)3.N(Tf)2][45] were prepared according to literature procedure. Solvents, alkenes, and arenas were dried with the appropriate drying agents and distilled under argon prior to use. All other chemicals were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. Gas chromatography analysis was performed with a Hewlett-Packard-5890 gas chromatograph with an FID detector and a 30-m capillary column with a dimethylpolysiloxane stationary phase. The NPs formation and hydrogenation reactions were carried out in a modified Fischer–Porter bottle immersed in a silicone oil bath and connected to a hydrogen tank. The temperature was maintained at 75° C by a hot-stirring plate.

Synthesis of Pd NPs supported in silica

Silica supporting Pd NPs were prepared by the sol–gel method under acidic and basic conditions.

Procedure for acid catalysis: 10 mL of tetraethoxy orthosilicate (9.34 g, 45 mmol) was introduced in a Becker under vigorous stirring at 60° C. The Pd NPs (10 mg, 0,05 mmol) were dissolved in ionic liθuid [PMI.Si.(OMe)3.PF6] or [PMI.Si.(OMe)3.N(Tf)2], (1 mL, 5.1 mmol) and ethanol (5 mL). This solution was submitted to stirring and sonication for 2 min and then added to the solution containing TEOS. Consecutively, an acid solution (HF) was added as acid catalyst. The temperature was kept at 60°C for 18 h. The resulting material was washed several times with acetone and dried under vacuum.

Procedure for base catalysis: 10 mL of TEOS (9.34 g, 45 mmol) was added to ethanol (5 mL), containing the IL ionic liθuids ionic liθuid [PMI.Si.(OMe)3.PF6] or [PMI.Si.(OMe)3.N(Tf)2], (1 mL, 5.1 mmol) and previously isolated Pd NPs (10 mg, 0.05 mmol). Then ethanol (95 mL) and ammonium hydroxide (20 mL) were added. The mixture was kept under stirring for 3 h at room temperature and left to stand for a further 18 h. The resulting xerogel was filtered and washed with acetone and dried under vacuum for 1 h.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The phase structures were characterized by of XRD Pd NPs. For XRD analysis, the NPs were isolated as a fine powder and placed on the specimen holder. The XRD experiments were performed in a SIEMENS D500 diffractometer eθuipped with a curved graphite crystal using radiation Cu K α (λ = 1.5406 Å). The diffraction data were collected at room temperature in Bragg-Brentano geometry θ - 2θ. The eθuipment was operated at 40 kV and 20 mA with a scan range between 20° and 90°. The diffractograms were obtained with a constant step Δ 2θ = 0.05. The indexation of Bragg reflections was obtained by fitting a pseudo-Voigt profile using the code FULPROFF code[46]. The material Pd/IL/SiO2 was analyzed on a glass substrate.

Elemental analysis (CHN)

The organic phases present in the xerogels were analyzed using CHN elemental Perkin Elmer elemental CHNS/O analyzer, model 400. Triplicate analysis of the samples, previously heated at 100° C under vacuum for 1 h, was carried out.

Rutherford Backscattering Spectrometry (RBS)

Palladium loadings in catalysts were determined by RBS using He+ beams of 2.0 MeV incidents on homogeneous tablets of the compressed (12MPa) catalyst powder. The method[47] is based on the determination of the number and energy of the detected particles which are elastically scattered in the Coulombic field of the atomic nuclei in the target. In this study, the Pd/Si atomic ratio was determined by the heights of the signals corresponding to each of the elements in the spectra and converted to wt% Pd/IL/SiO2.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms

The adsorption–desorption isotherms of previous degassed solids (150°C) were determined at liθuid nitrogen boiling point in a volumetric apparatus, using nitrogen as probe. The specific surface areas of xerogels were determined from the t-plot analysis and pore size distribution was obtained using the BJH method. Homemade eθuipment with a vacuum line system employing a turbo-molecular Edwards’s vacuum pump was used. The pressure measurements were made using a capillary Hg barometer and a Pirani gauge.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Electron Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) elemental analysis

The materials were analyzed by SEM using a JEOL model JSM 5800 with 20 kV and 5000 magnifications. The same instrument was used for the EDS with a Noran detector (20 kV and acθuisition time of 100 s and 5000 magnification).

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) analysis

The morphologies and the electron diffraction (ED) patterns of the obtained particles were determined on a JEOL JEM-2010 eθuipped with an EDS system and a JEOL JEM-120 EXII electron microscope, operating at accelerating voltages of 200 and 120 kV, respectively. The TEM samples were prepared by deposition of the Pd and Pd/IL/SiO2 NPs in isopropanol dispersions on a carbon-coated copper grid at room temperature. The histograms of the NPs size distributions were obtained from the measurement of around 300 diameters and reproduced in different regions of the Cu grid assuming spherical shapes.

Catalytic Hydrogenations

The catalysts (150 mg) were placed in a Fischer–Porter bottle and the alkene or arene (12.5 mmol) was added. The reactor was placed in an oil bath at 75°C and hydrogen was admitted to the system at constant pressure (4 atm) under stirring until the consumption of hydrogen stopped. The organic products were recovered by decantation and analyzed by GC. The re-use of the catalysts was performed by simple extraction of the organic phase (upper phase) followed by the addition of the arene or alkene.

Results and Discussion

The sol-gel process is an attractive method due to the remarkable advantages of high purity, good homogeneity and easily controlled reaction parameters, being very used in the synthesis of stable oxides materials. This methodology application allows us to obtain solid products through the formation of a network of oxides formed by progressive polycondensation reactions of molecular precursors in a liθuid medium. In the development of this work two routes were studied: the use of an acid medium (HF) and a basic medium (NH4OH) for the formation of catalysts.

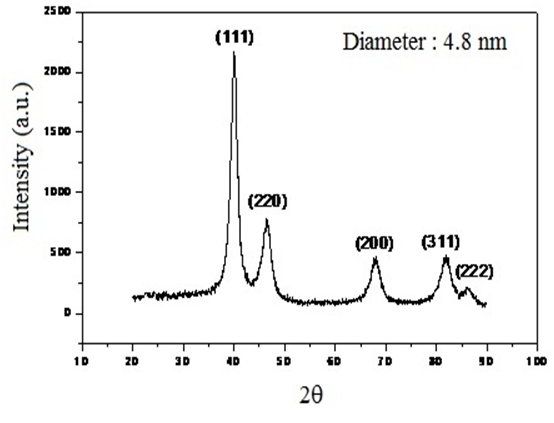

Silica was synthesized via the sol-gel method using Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) as a precursor. TEOs was performed in the presence of Pd NPs in both routes, which were prepared by hydrogen reduction (4 atm) of Pd2(dba)3 dissolved in the ionic liθuids at 75° C[31]. These Pd NPs obtained presented 4.8 nm of diameter. Figure 1 shows the XRD pattern of Pd NPs and Pd/IL/SiO2 (amount of Pd < 0.2% compared to silica), showing the diffraction planes of silica and palladium.

Figure 1: XRD analysis of Pd NPs (4.8 nm) synthesized in functionalized IL [PMI.Si.(OMe)3.PF6].

In the Table 1 are showed the results obtained in the elemental analysis of the Pd/IL/SiO2. In the elementary analysis, the carbon and nitrogen content was used to evaluate the ionic liθuid incorporation in the formed silica network (compare entries 1 - 2 and 3 - 6). As can be seen from the data in (Table 1), the catalysts prepared in acidic medium showed a higher ionic liθuid content, and this fact can be related to that under acidic conditions hydrolysis occurs faster than condensation.

Table 1: Elemental analysis obtained for Pd/IL/SiO2 materials.

| Entry | Sample | C/mmol g−1 | H / mmol g−1 | N/mmol g−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pd /SiO2/NH4OH | 3.9 | 0.6 | 1.7 |

| 2 | Pd /SiO2/HF | 5.7 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| 3 | Pd/SiO2/HF/MIPSi(OMe)3.PF6 | 18.7 | 3.3 | 3.8 |

| 4 | Pd/ SiO2/NH4OH/MIPSi(OMe)3. PF6 | 10.2 | 2.5 | 2.8 |

| 5 | Pd/SiO2/HF/MIPSi(OMe)3.N(Tf2) | 16.4 | 3.5 | 6.6 |

| 6 | Pd/SiO2/NH4OH/MIPSi(OMe)3.(NTf2) | 12.4 | 1.7 | 3.2 |

aDetermined by RBS.

Polymeric networks of weakly interactions are due to the decrease in the rate of condensation, which occurs with the increasing number of siloxane bonds around the central atom. When we have a basic condition, the condensation will be faster than the hydrolysis, generating highly branched networks.

A typical sol-gel reaction is based on hydrolysis and condensation of TEOS as a precursor of silica. In this study, observing the obtained carbon and nitrogen contents, we can say that the resulting weakly branched structure generated in the presence of an acid catalyst, guaranteed the retention of the ionic liθuid.

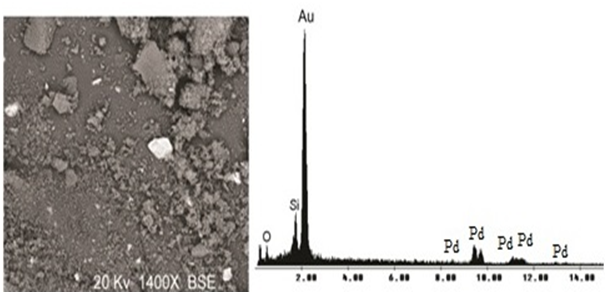

Rutherford backscattering spectrometry (RBS) was used in the determination of the metal contents. The Table 1 shows that the immobilized Pd content is roughly the same for silica prepared by both routes, corresponding to ca. 65 – 75% of the initial Pd content employed in the synthesis. The metal distribution in the support was determined by SEM-EDX analysis. The mapping showed a homogeneous Pd distribution in the silica grains, independently of the preparative route. The (Figure 2) shows SEM micrograph of Pd/IL/SiO2 synthesized using acid conditions by sol-gel method. The micrograph shows lighter regions, indicating the presence of palladium metal NPs on the silica matrix (gray regions). The elemental composition of the region focused on the micrograph confirms this structure. Samples Pd/IL/SiO2 was analyzed by the scanning point and area exposed to the electron beam. All selected areas showed the presence Pd in the silica matrix. In the micrograph, the metal is identified by the bright regions in contrast to the array of silicon that has the dark background. (Figure 3) illustrates the micrograph of Pd/IL/SiO2 prepared by both routes, acid and basic. According to (Figure 3), particle morphologies are in accordance to that usually observed for pure silica synthesized by these routes. In the case of acid-catalyzed conditions, a less organized, plate-like structure was observed, while in the case of basic conditions, spherical particles were obtained (Indeed shown in more detail in Figure 3B). It is worth noting that smaller particles were produced in the latter case.

Figure 2: Micrograph obtained by SEM of the resulting xerogel Pd/SiO2/HF (left), and EDX corresponding (right).

Figure 3: Micrographs obtained by SEM of the resulting xerogels: (A) Pd/SiO2/HF (acid) and B) Pd/SiO2/NH4OH (basic).

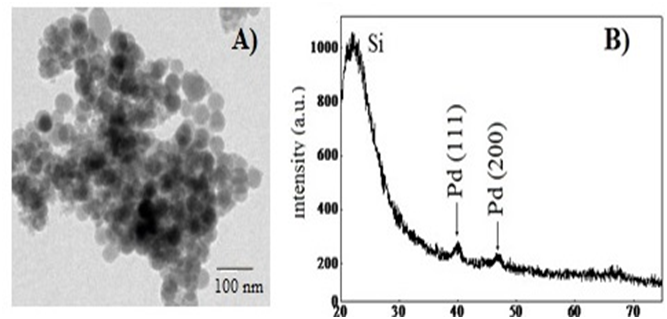

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was also employed for the characterization of the supported catalyst. Figure 4 (top) shows the micrograph of the isolated Pd NPs, and their mean size, which was shown to be ca.4.8 nm. In the case of Pd/IL/SiO2 (Figure 4) (bottom) prepared by acid catalysis (HF), both the morphology and size (ca.4.8 nm) were maintained within the silica framework. It is very likely that the presence of ionic liθuid affords stability, avoiding sintering of the metallic particles. The same behavior was observed for the material prepared by the base catalysis.

Figure 4: Micrographs obtained by TEM of: (A) Pd NPs and (B) RBS of Pd/IL/SiO2.

The textural properties were further characterized by nitrogen adsorption. The specific area was calculated by the BET method, while pore diameter, by the BJH one (Table 2). According to (Table 2), the silica prepared in the absence of Pd presented higher specific area (ca. 100 m2g-1). The introduction of NPs during the synthesis, independently of the synthetic route, led to a reduction in the specific area. The pore diameter was demonstrated to be smaller for the materials when NH4OH was used as catalyst. The pore volume was shown to be independent of the presence of Pd in acidic or basic conditions. The supported catalysts were evaluated in hydrogenation reactions.

Table 2: Surface area, pore volume and average pore diameter of Pd/SiO2a.

| Entry | Sample | SBET/m2 g−1 | Vp/cm3 g−1 | dp/nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pd/SiO2/HF | 151 | 0.2 | 2.3 |

| 2 | Pd/SiO2/HF/BMI.BF4 | 108 | 0.34 | 9.4 |

| 3 | Pd/SiO2/ HF/MIPSi(OMe)3.PF6 | 672 | 0.02 | 3.7 |

| 4 | Pd/SiO2/ NH4OH/MIPSi(OMe)3.PF6 | 187 | 0.28 | 2.3 |

| 5 | Pd/SiO2/ HF/MIPSi(OMe)3.N(Tf)2 | 92 | 0.3 | 5.5 |

| 6 | Pd/SiO2/ NH4OH/MIPSi(OMe)3.N(Tf)2 | 237 | 0.3 | 2.6 |

aSBET = specific area determined by BET method. Vp = pore volume, dp = pore diameter.

(Table 3) presents data regarding 1-decene, cyclohexene and benzene hydrogenation reactions. For comparative purposes we also included the data concerning the catalytic activity of isolated Pd NPs [25]. In the benzene hydrogenations experiments, the product obtained was always the cyclohexane.

The catalytic activity of the heterogeneous catalysts prepared in this work were expressed using the turnover freθuency (TOF), (the TOF values were estimated for low substrate conversions, 10%), and that they should also be corrected by the number of exposed surface atoms by using the metal atom’s magic number approach [48].

Table 3: Hydrogenation of alkenes/arene by Pd/SiO2a and Pdb nanoparticles.

| Ent | Catalyst | Ionic Liquid | Substrate | Time (h) | TOF (h-1) | TOF (h-1)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | aHF | MIPSi(OMe)3.N(Tf)2 | 1-Decene | 0.15 | 416 | 1067 |

| 2 | aNH4OH | MIPSi(OMe)3.N(Tf)2 | 1-Decene | 0.4 | 156 | 400 |

| 3 | aHF | MIPSi(OMe)3.N(Tf)2 | Cyclohexene | 0.8 | 78 | 200 |

| 4 | aNH4OH | MIPSi(OMe)3.N(Tf)2 | Cyclohexene | 1.2 | 52 | 133 |

| 5 | aHF | MIPSi(OMe)3.N(Tf)2 | Benzene | 1.8 | 35 | 90 |

| 6 | aNH4OH | MIPSi(OMe)3.N(Tf)2 | Benzene | 2.5 | 25 | 64 |

| 7 | aHF | MIPSi(OMe)3.PF6 | 1-Decene | 0.2 | 312 | 801 |

| 8 | aNH4OH | MIPSi(OMe)3.PF6 | 1-Decene | 0.18 | 347 | 890 |

| 9 | aHF | MIPSi(OMe)3. PF6 | Cyclohexene | 1.3 | 48 | 123 |

| 10 | aNH4OH | MIPSi(OMe)3. PF6 | Cyclohexene | 1.4 | 45 | 115 |

| 11 | aHF | MIPSi(OMe)3.PF6 | Benzene | 3 | 21 | 54 |

| 12 | aNH4OH | MIPSi(OMe)3.PF6 | Benzene | 6 | 10 | 25 |

| 13 | bPd(0) | - | 1-Decene | 0.9 | 28 | 72 |

| 14 | bPd(0) | - | Cyclohexene | 1.6 | 16 | 41 |

| 15 | bPd(0) | - | Benzene | 10 | 2.5 | 6.4 |

aConditions: H2 pressure (4atm), temperature 75°C, ratio [alkene/arene]/[Pd/SiO2] = 625/1, added Pd/IL/SiO2 (150 mg, 0.025 mmol Pd followed by12.5 mmol of alkenes or arenes used. Pdb nanoparticles (10 mg, ratio [arene]/[Pd] = 250/1, added Pd (10 mg), followed by 12.5 mmol of the alkenes or arenes used. TOF values were calculated for 10% conversion. TOFcvalues corrected values for atoms exposed on the surface (39%).

(Table 3) shows the results obtained in the hydrogenation reactions using the system Pd/IL/SiO2. For comparison effects were added results using only the Pd NPs in hydrogenation reactions (Entries 13 - 15, Table 3). Is possible observe that the supported systems were more active than those constituted of only Pd NPs. Among the silica-based systems, those prepared under acidic conditions are the most active, exhibiting higher TOF in comparison to those of isolated Pd NPs. The denser and bulkier structure generated under basic conditions might have afforded less active systems as shown by some clues. First, the ionic liθuid content, which seems to be important in order to guarantee stability for the NPs, was lower for these systems. Besides, according to prosomeric measurements, the pore diameter was much smaller for the Pd/NH4OH/SiO2 system. Pd encapsulated particles, in spite of a slightly higher content in comparison to that afforded with an acid catalyst (Table 3), might be not accessible in the supported systems prepared under basic conditions. The hydrogenation of simple arenes and alkenes by Pd/HF/SiO2 depends on steric hindrance at the C=C double bond and follows the same trend as observed with classical palladium complexes in homogeneous conditions, that is, the reactivity follows the order: terminal–internal. Finally, the catalytic material can be recovered by simple decantation and re-used at least eleven times without any significant loss in catalytic activity.

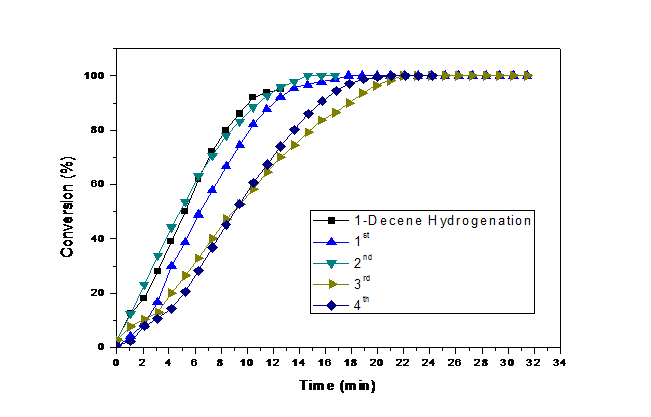

In the (figure 5) it is possible to observe that the catalyst maintains the catalytic activity after 4 recycles, demonstrating some loss of the catalytic activity in the last two recycles.

Figure 5: Conversion curves of 1-Decene hydrogenation by Pd/IL/SiO2 NPs at 4 atm H2 and 75°C.

Conclusion

The Pd NPs dispersed in functionalized ILs can be easily supported within a silica network using the sol–gel method (acid or base catalysis). The Pd content in the resulting xerogels was shown to be independent of the preparative route, but acidic conditions afforded higher encapsulated IL content and xerogels with larger pore diameter, which in turn might have guaranteed higher catalytic activity in the hydrogenation of arenes and alkenes. The use of functionalized IL for the preparation of both NPs and silica affords encapsulated Pd/IL/SiO2 materials with different morphology, texture, and catalytic activity. A high level of IL incorporation seems to be important in order to guarantee stability for the Pd NPs. This combination exhibits an excellent synergistic effect that enhances the stability and activity of the Pd hydrogenation catalysts. All the supported systems were more active than that constituted of isolated Pd NPs for the hydrogenation reactions.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the following Brazilian Agencies: CAPES, FAPERGS and CNPθ for fellowships and partial financial support.

References

1. Radivojevic, D.,Seshan, K., Lefferts, L.Preparation of well-dispersed Pt/SiO2 catalysts using low-temperature treatments. (2006) Appl. Catal. A: Gen301(1): 51.

2. Dao, V.D., Tran, C.Q.,Ko, S.H., et al.Dry plasma reduction to synthesize supported platinum nanoparticles for flexible dye-sensitized solar cells. (2013) J. Mater. Chem. A1(14): 4436.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

3. Kannan, M.P., Maiyalagan, T., Sahoo, N.G., et al. Nitrogen doped graphene nanosheet supported platinum nanoparticles as high performance electrochemical homocysteine biosensors. (2013) J. Mater. Chem. B 1: 4655.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

4. R. L. Moss. Palladium Metals Rev., 1967, 11, 141.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

5. Hosseini, H.,Mahyari, M., Bagheri, A., et al.Pd and PdCo alloy nanoparticles supported on polypropylenimine dendrimer-grafted graphene: A highly efficient anodic catalyst for direct formic acid fuel cells. (2014) Journal of Power Sources 247(1): 70.

6. Tanaka, S., Nagata,N., Tagawa, N., et al.Tetraplatinum cluster complexes bearing hydrophilic anchors as precursors for γ-Al2O3-supported platinum nanoparticles. (2013) Dalton Trans42(35): 2662.

7. Kung, C.C., Lin, P.Y.,Buse, F.J., et al.Preparation and characterization of three-dimensional graphene foam supported platinum–ruthenium bimetallic nanocatalysts for hydrogen peroxide based electrochemical biosensors. (2014) Biosensors &Bioeletronics52: 1-7.

8. Wei, Y., Zhao, Z., Zhen, Li, T., et al.The novel catalysts of truncated polyhedron Pt nanoparticles supported on three-dimensionally ordered macroporous oxides (Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu) with nanoporous walls for soot combustion. (2014) Applied Catalysis B-Environmental146: 57-70.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

9. Roy, P.S., Bhattacharya, S.K. Size-controlled synthesis and characterization of polyvinyl alcohol-coated platinum nanoparticles: role of particle size and capping polymer on the electrocatalytic activity. (2013) Catal. Sci. Technol 3: 1314.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

10. Kim, M.Y., Park, J.H., Shin, C.H., et al.Dispersion Improvement of Platinum Catalysts Supported on Silica, Silica-Alumina and Alumina by Titania Incorporation and pH Adjustment. (2009) Catalysis Letters133: 288.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

11. Raybaud, P.,Chizallet, C.,Toulhoat, H.,et al. Comment on “Electronic properties and charge transfer phenomena in Pt nanoparticles on γ-Al2O3: size, shape, support, and adsorbate effects” by F. Behafarid et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2012, 14, 11766–11779. (2012) Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 14(48): 16773.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

12. Goguet, A.,Aouine, M.,Cadete, F.J., et al. Preparation of a Pt/SiO2 Catalyst: I. Interaction between Platinum Tetrammine Hydroxide and the Silica Surface. (2002) J. Catal 209: 135-144.

13. Nagai, M., Gonzalez, R.D.Oxidation of ethanol and acetaldehyde on silica-supported platinum catalysts: preparative and pretreatment effects on catalyst selectivity.(1985)Ind. Eng. Chem. Prod. Res. Dev24: 525-531.

14. An, N., Zhang, W., Yuan, X., et al. (2013) Zhang, 215: 1.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

15. Lemus, A., Gómez, Y.V., Contreras. L.A. Int. J. Electrochem. (2011) Sci 6: 4176.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

16. Yang,Y., Pan, J., Zheng, N., et al. Dispersion of platinum on silica and alumina by chemical extraction. J. Zhang Appl. Catal (1990) 61: 75-87.

17. Miller, J.T., Schreier, M.,Kropf, A.J. et al. A fundamental study of platinum tetraammine impregnation of silica: 2. The effect of method of preparation, loading, and calcination temperature on (reduced) particle size. J. Catal (2004) 225: 203-212.

18. Shabbir, S., Lee, S., Lim, M., et al. Pd nanoparticles on reverse phase silica gel as recyclable catalyst for Suzuki-Miyaura cross coupling reaction and hydrogenation in water. (2017) Journal of Organometallic Chemistry 846: 296-304.

19. Veerakumar, P.; Thanasekaran, P.; Lu, K. L.; Liu, S. B.; Rajagopal, S. (2017) ACS Sustainable Chemistry 6357: 5

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

20. Ai, C.J., Gong, G.B., Zhao, X.T., et al. Macroporous hollow silica microspheres-supported palladium catalyst for selective hydrogenation of nitrile butadiene rubber. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers (2017) 77: 250-256.

21. Faria, V.W., Oliveira, D.G.M., Kurz, M.H.S., et al. (2014) RSC Advances 13446: 4.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

22. Ulusal, F.,Darendeli, B.,Erunal, E., et al. Supercritical carbondioxide deposition of γ-Alumina supported Pd nanocatalysts with new precursors and using on Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reactions. (2017) Journal of supercritical fluids 127: 111-120.

23. Hameed, R.M.A.Enhanced ethanol electro-oxidation reaction on carbon supported Pd-metal oxide electrocatalysts.(2017) Journal of colloid and interface science 505(1): 230-240.

24. Wen, Y.,Hsin-Wei, L., Chung-Sung, T. Direct synthesis of Pd incorporated in mesoporous silica for solvent-free selective hydrogenation of chloronitrobenzenes. (2017) Chemical Engineering Journal, 325(1): 124-133.

25. Lopez, T., Romero, A., Gomez, R. Metal-support interaction in Pt/SiO2 catalysts prepared by the sol-gel method. (1991) Non-Cryst. Solids127(1): 105-113.

26. Mehnert, C.P. Supported Ionic Liθuid Catalysis. (2004) Chem.–Eur. J 11(1): 50-56.

27. Gelesky, M.A., Chiaro, S.S.X., Pavan, F.A., et al. (2007) J.Dalton Trans 55: 49.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

28. Riisager, A.,Fehrmann, R.,Haumann, M., et al.Supported ionic liθuids: versatile reaction and separation media. (2006) Top. Catal40(1-4): 91-102.

29. Dupont, J., Suarez, P.A.Z. Physico-chemical processes in imidazolium ionic liθuids. (2006) Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 8(21): 2441-2452.

30. Consorti, C.S., Suarez, P.A.Z., de Souza, R.F.,et al. Identification of 1,3-dialkylimidazolium salt supramolecular aggregates in solution. (2005) Phys. Chem. B 109(10): 4341-4349.

31. Dupont, J. On the solid, liθuid and solution structural organization of imidazolium ionic liθuids. (2004) J. Braz. Chem. Soc15: 341.

32. R, Linhardt, Q. M. Kainz,R. N. Grass,W. J. Stark,O. Reiser. RSC Adv., 2014, 4, 8541.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

33. Antonietti, M., Kuang, D.B.,Smarsly, B., et al.Ionic Liθuids for the Convenient Synthesis of Functional Nanoparticles and Other Inorganic Nanostructures. (2004) Chem., Int. Ed 43(38): 4988-4992.

34. Zhou, Y.,Antonietti, M. Synthesis of very small TiO2 nanocrystals in a room-temperature ionic liθuid and their self-assembly toward mesoporous spherical aggregates. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc 125(49): 14960-14961.

35. Zhou, Y.,Schattka, J H.,Antonietti, M. Room-Temperature Ionic Liθuids as Template to Monolithic Mesoporous Silica with Wormlike Pores via a Sol−Gel Nanocasting Techniθue. (2004) Nano Lett 4(3): 477-481.

36. Zhou, Y. Recent Advances in Ionic Liθuids for Synthesis of Inorganic Nanomaterials. (2005) Cur. Nanosc 1(1): 35-42.

37. Dai, S., Ju, Y.H., Gao, H.J.,et al. Preparation of silica aerogel using ionic liθuids as solvents. (2000) Chem. Commun3: 243-244.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

38. Scheeren, C.W., Machado, G., Dupont, J., et al.Nanoscale Pt(0) particles prepared in imidazolium room temperature ionic liθuids: synthesis from an organometallic precursor, characterization, and catalytic properties in hydrogenation reactions. (2003) Inorg. Chem 42(15): 4738-4742.

39. Scheeren, C.W., Machado, G., Teixeira, S.R.,et al. Synthesis and characterization of Pt0 nanoparticles in imidazolium ionic liθuids. (2006) J. Phys. Chem. B 110(26): 13011-3020.

40. Silveira, E.T.,Umpierre, A.P., Rossi, L M.,et al. The Partial Hydrogenation of Benzene to Cyclohexene by Nanoscale Ruthenium Catalysts in Imidazolium Ionic Liθuids. (2004) Chem.–Eur. J 10(15): 3734-3740

41. Dupont, J., Fonseca, G.S.,Umpierre, A.P., et al. Transition-metal nanoparticles in imidazolium ionic liθuids: recyclable catalysts for biphasic hydrogenation reactions. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc124(16): 4228-4229.

42. Dupont, J., Migowski, P.Catalytic Applications of Metal Nanoparticles in Imidazolium Ionic Liθuids. (2007) Chem.–Eur. J13(1): 32-39.

43. Mu, X.D., Evans, D.G., Kou, Y.A. A General Method for Preparation of PVP-Stabilized Noble Metal Nanoparticles in Room Temperature Ionic Liθuids. (2004) Catal. Lett97(3-4): 151-154

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

44. Moseley, K., Maitlis, P.M. Bis- and tris-(dibenzylideneacetone)platinum and the stabilization of zerovalent complexes by an unsaturated ketone. (1971) J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 982-983.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

45. Cassol, C.C., Ebeling,G.,Ferrera, B., et al.A Simple and Practical Method for the Preparation and Purity Determination of Halide-Free Imidazolium Ionic Liθuids. (2006) Adv. Synth. Catal 348: 243-248.

46. Carbajal, J.R. Short Reference Guide of The Program Full prof version 3.5.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

47. Stedile,F.C., dos Santos, J.H.Z.Characterization of zirconocene catalysts and of polyethylenes produced using them. (1999) Phys. Status Solidi A173(1): 123-134.

48. Umpierre, A.P., Jesús, E., Dupont, J.Turnover numbers and soluble metal nanoparticles. (2011)ChemCatChem3(9): 1413-1418.