A Systematic Review for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Sonia Binte Wahed1*, Philip Boughton1,Tania Binte Wahed2, Md. Shahriar Hossain3, Enamul Haque3,4*,Andrew Ruys1

Affiliation

- 1Biomedical Engineering Design Lab, School of Aerospace Mechanical and Mechatronic Engineering, University of Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2Department of Pharmacy, Jahangirnagar University, Bangladesh

- 3ISEM, Australian Institute for Innovative Materials, University of Wollongong, NSW, Australia

- 4School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, The University of Sydney, NSW, Australia

Corresponding Author

Enamul Haque, ISEM, Australian Institute for Innovative Materials, University of Wollongong, NSW, Australia , School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, The University of Sydney, NSW, Australia, E-mail: enamul.haque@sydney.edu.au,

Sonia Binte Wahed, Biomedical Engineering Design Lab, School of Aerospace Mechanical and Mechatronic Engineering, University of Sydney, NSW, Australia, E-mail: sbin6815@uni.sydney.edu.au

Citation

Haque, E., et al. A Systematic Review for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. (2016) J Anesth Surg 3(1): 119-127.

Copy rights

© 2016 Haque, E. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Anterior cruciate ligament; Ligament graft; Scaffold; Biomaterials; Polymer

Abstract

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the major ligaments in human knee. ACL can be injured from mild to severe and once it ruptured it doesn’t heal itself because of its complex structure. Many studies have been done for the reconstruction of ACL according to their structures and mechanical properties but none has fulfilled all the requirements. In this review structure of ligament, ligament injuries, synthetic ligaments, design requirements everything has been discussed.

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament rupture is more common nowadays and it can lead to cartilage degeneration and osteoarthritis[1]. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is frequent[2] and one of the challenging work in tissue engineering[3]. Anterior cruciate ligament is important for maintenance of knee movement[4]. ACL do not heal itself because of its intrinsically poor healing potential and surgical mediation is usually required[5,6]. Allograft and autograft were used for ACL reconstruction[7,8]. Due to several drawbacks of allograft and autograft synthetic grafts are the main option for ACL reconstruction[9].

Ligaments are made of bands of strong collagenous connective tissue. These paralleled collagen bundles attached to each other by crosslinking[10]. Mesenchymal cells produce this type of tissue; it can differentiate into fibroblast cells. These fibroblast cells again differentiate into fibrocytes cells. After maturation of fibrocytes they become inactive and produce ligaments. Ligaments attach two bones together at a joint, prevent dislocations of the joints, and restrain the movements of the joints.

Ligaments contain two-thirds water and one-third solid. Collagen is the solid component of the ligament basically collagen types I and rests of the types are III, VI, XI and XIV. To maintain a considerable range of mechanical and biological properties of soft tissues, related organ systems, and bone collagen plays a vital role[11].

Structure of ACL

ACL is not isometric[12]. ACL is made of collagen bundles which are paralleled and cross linked to each other. These bundles vary the tension among the fibers of the ligament[13]. Fibroblasts are joined to the bundles individually. It can produce new collagen and remove old collagen by enzymatically break down process. These collagen fibers give high tensile strength to the ACL. The linear modulus, maximum stress, and strain energy density to maximum stress of the ACL were significantly less than similar properties for patellar tendons[14]. Its role is essential for normal movement and assures joint stability[15]. Age, weight, and activity level are the key factors to influence the mechanical properties of ACL[16]. Injury of the ACL frequently occurs in the young and physically active population and is responsible for a loss of mobility and life’s comfort[17].

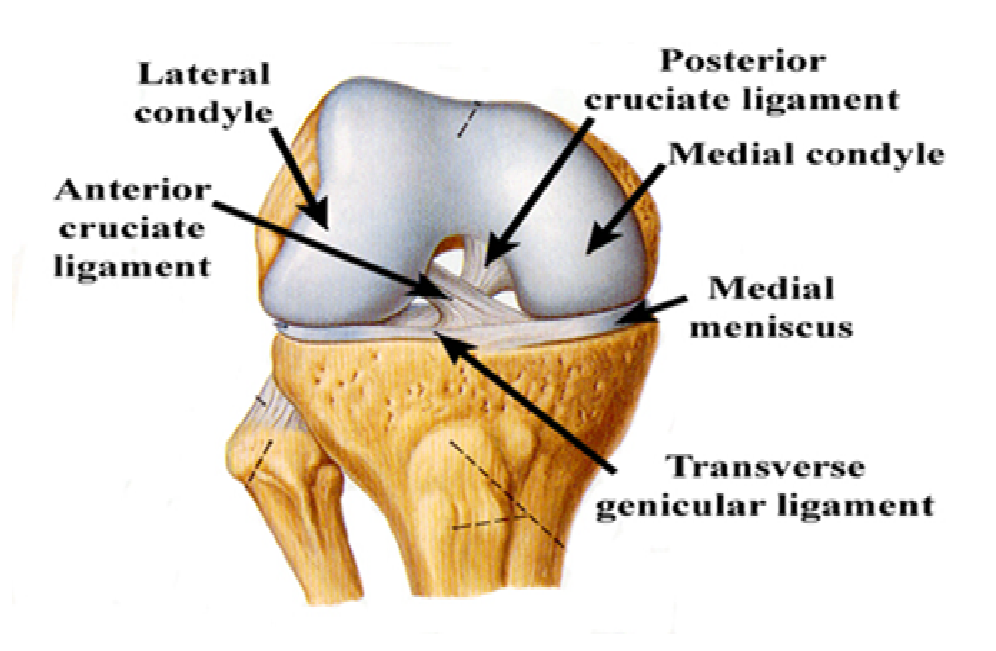

Figure 1: Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) of a normal ligament.

Clinical Problems Related to ACL Injury

ACL injury more commonly causes knee instability that does injury to other knee ligaments. Injuries of the ACL range from mild such as small tears to severe when the ligament is completely torn. ACL can be torn in many ways. ACL injuries are common in soccer, floor ball and downhill players.8 9 ACL rupture can be examined by Lachman test and Pivot shift test[18]. The anterior drawer test is performed on a patient in a supine position, hip flexed at 45º and the knee flexed at 90º, foot is then stabilized and tibia is pushed forward on the femur. In Lachman test patient should be on supine position but the knee flexed at 30º. The third test is pivot shift test.

Zantop et al studied that around 56% of the patients suffered from complete rupture of two bundles at same location, for some patients PL can stay intact but all AM bundles had ruptured. The frequency of injury depends on mechanism of injury: medial meniscus tear (25 - 31%), lateral meniscus tear (2 - 41%), medial collateral ligament injury (15 - 50%), lateral collateral injury (4 - 8%).

Treatment of ACL Rupture

MRI has chosen the best option for the diagnosis of ACL rupture. The sensitivity of MRI for acute ACL rupture is 90%. Many research has been done to restore the activity and function of ACL. Among them surgery with allograft, autograft, and synthetic grafts are gold standard for ACL treatment[19].

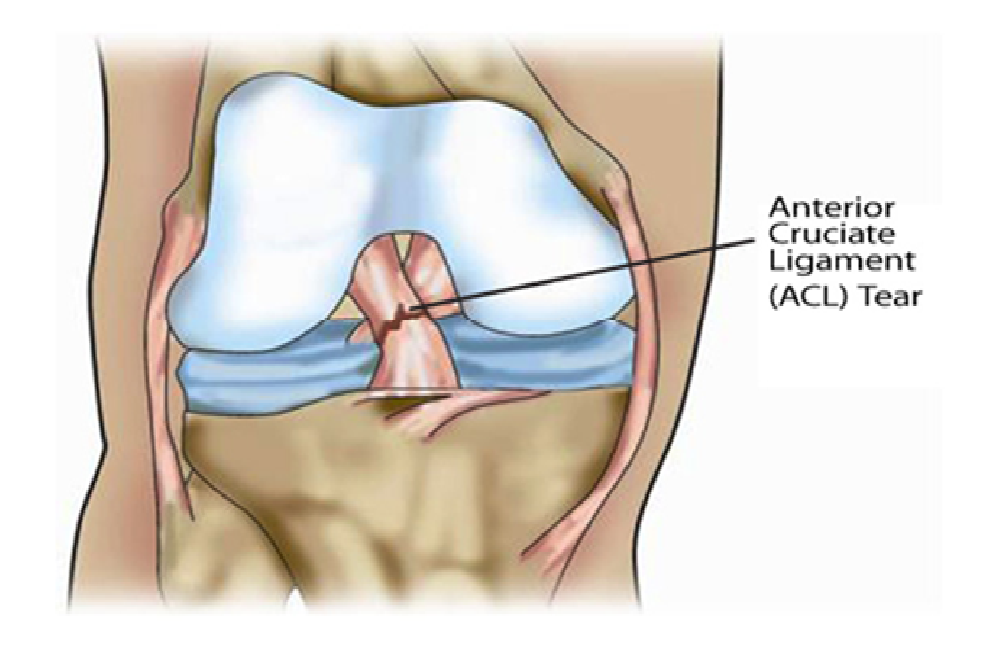

Figure 2: Rupture of ACL after injury.

Autografts

Most surgeons have preferred autograft and the most two common autografts are Bone-Patellar-tendon-bone (BPTB) and HTs[20]. Less risk of donor site morbidity, superior mechanical properties autografts are preferred to allograft[21].

BPTB is the most commonly used autograft for young and active populations. The graft is generally chosen from the middle one third of patellar tendon, its better incorporation and faster healing promises it as a desired graft for ACL reconstruction[22].

Quadruple strand Hamstring tendons has the similar characteristics like BPTB[23-25]. Due to donor site morbidity, anterior knee pain, and increased risk of patellar fracture some surgeons suggest to use HT than BPTB graft[26]. Besides the good performance HT also has some drawbacks like weakness of remaining hamstrings[27 - 30], internal rotator musculature[31], and isokinetic knee flexor torque was higher in BPTB than HT[32].

Quadriceps tendon with or without a patellar bone block is getting popularity besides BPTB and HT[33]. This graft preserves hamstring function and avoid complications associated with BPTB and HT[34]. There are several disadvantage of this graft include difficulty during graft harvest and curved proximal patellar surface etc[35].

Allograft

Allograft could avoid donor site complications such as patellar fracture, muscle weakness and knee pain[36,37]. Several types of allograft can be used, including patellar tendon, quadriceps tendon, Achilles tendon, tibialis anterior tendon, tibialis posterior tendon, hamstring tendon, and fascia lata[38].

Achilles tendon is an option because of its favorable mechanical properties[39,40], no concern for graft tunnel length mismatch[1], graft diameter is easily matched to the patients, more cylindrical than patellar graft, has a greater cross- sectional area which gives better strength[41,42]. Tibialis anterior allografts have similar strength to quadrupled hamstring graft[43,44].

Allograft undergo a similar process of incorporation like autograft[45]. Autograft can cause donor site morbidity, including various complications like anterior knee pain, pain when kneeling, patellar fracture[46], patellofemoral crepitation[47], numbness caused by damage of the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve, and possible loss of quadriceps strength[48].

Allograft is expensive and delayed graft incorporation in compared with autograft[49]. Due to the drawbacks of Allograft and auto grafts synthetic ligament graft is now the main attraction for ACL reconstruction. Auto graft can cause donor site morbidity and allograft may cause blood bone diseases to the patients[50]. Currently, motion limitations are the most common complications of ACL reconstructions for augmented devices. Early rehabilitation have been invented to minimize these types of problems but when the biological graft is very weak this increased activity takes place during the early post-operative period. Throughout the early rehabilitation excessive stress on graft could cause damage to the graft tissue, resulting rupture of the graft. Thus, in the non-augmented graft, the advantage of early rehabilitation to improve range of motion must be balanced against the risk of overloading the weak postoperative graft[51].

Synthetic ligament

Synthetic ligament is an artificial ligament device for joining the ends of two bones. The device composed of a multilayered or tubular woven ligament having an extra-articular region, at least one bend region, at least one end region. Each region should be woven to give support and flexibility to the particular types of stresses[52].

Some other advantages of synthetic ligament graft: (i) shorter operation times, (ii) lesser patient morbidity, (iii) economically efficient treatment, and (iv) lower risk of postoperative infection[53].

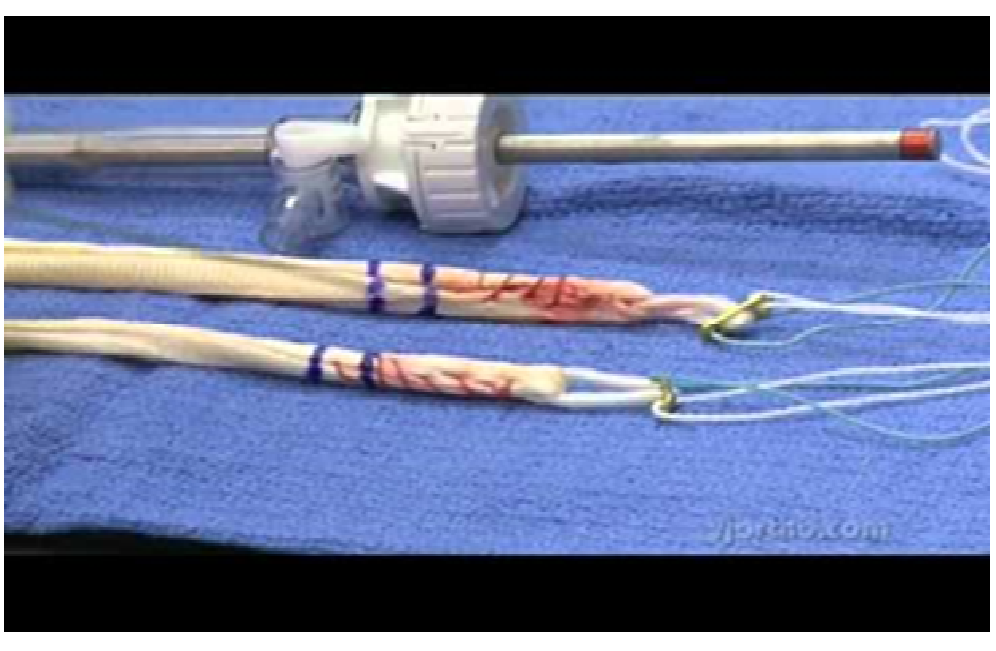

Figure 3: Artificial ligament devices for joining the ends of two bones.

Characteristics of Ligament Graft

• Graft must be strong but have just the right stiffness to match the compliance of a normal ACL.

• Provoke a minimal degree of inflammation or toxicity in vitro.

• Controlled biodegradability to aid the formation of new tissue

• Ligament should have good resistance to abrasion against bones and joints[54].

Tissue Engineering and Scaffold

Tissue engineering is clarified as the application of biological, chemical and engineering principles toward the repair, restoration or regeneration of living tissues, which must have the following criteria[55].

Porosity

Porosity is one of the major requirement of a scaffold, it allows cell seeding or resettling throughout the materials and pore size is important for tissue ingrowth, it determines the internal surface area available for cell attachment[56]. A large surface area is essential for high number of cells, sufficient to rehabilitate organ function, can be cultured[57,58]. Porosity can regulate the performance and cellular response of the implant[55].

Mechanical Properties

Mechanical properties of the scaffold are often of critical importance especially when regenerating hard tissues such as ligament, tendon, cartilage, and bone. Artificial ACL perfectly mimics all the characteristics of a normal ACL in terms of strength, compliance, elasticity and durability without any side effects[59].

Biocompatibility

Zigang Ge published that in ligament tissue engineering cells and materials are two important fundamental, and so the interactions between them are important. Materials could interfere with cells adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation[60]. Cells could adhere to material surface by direct adhesion or by pre-absorbed protein[61]. Recently to modify the materials to improve their biocompatibility two common methods are used (i) coating with “biocompatible materials” (ii) graft modification with bio scaffold.

Table 1: Mechanical properties of materials for synthetic grafts compared to normal ACL

| Materials | Ultimate tensile strength(N) | Stiffness(N/mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Human ACL | 1730 | 242 |

| Human hamstring graft | 3790 | 776 |

| Human patellar-tendon graft | - | 685 |

| Carbon fibers | 660 | 230×109 |

| Gore-Tex prosthesis | 5300 | 322 |

| Dacron | 3631 | 420 |

| Twisted silk matrix | 2337 | 354 |

| Parallel silk matrix | 1740 | 2214 |

| KLAD | 280 | 1500 |

| Trevira | 68.3 | 1866 |

| Leeds Keio | 270 | 2000 |

| Braided PLGA | 907 | - |

| PLLA fiber | 175 | - |

Scaffolds Manufacturing Process

Scaffolds can be manufactured in many forms to give their required characteristics for specific applications. Fibres and fibre scaffolds are commonly made of natural polymers such as silk, collagen and synthetic polymers such as PLA, PLLA, PGA, PLGA, or glass[62,63].

Silk

Silk has been chosen from other synthetic and natural proteins[64-66] because (i) Silk has similar mechanical properties like ACL (ii) Biocompatible[67] (iii) Avoids Bioburdens (iv) in vitro in tissue culture conditions it can maintain mechanical tensile integrity. (v) In vivo it shows slow degradation[68]. A wire-rope silk fiber was successfully designed in case of biocompatibility of this fiber and matrix stiffness and strength to match the whole geometry of ACL[69]. For ACL reconstruction another Silk Fibroin knitted sheath with braided core (SF-KSBC) structure was prepared to perform different tasks, such as porous core structure to give strong mechanical support and the sheath structure to prevent the wear and to permit cell adhesion, proliferation, and migration towards the core[70,71]. A novel silk/TCP/PEEK scaffold (silk ACL scaffold blended onto the TCP scaffold and fixed with a PEEK anchor) was developed to mimic the human platelar- bone-tendon-bone autograft and it may hold promise as a good synthetic ACL graft[72]. By maintaining ligament matrix and gene expression and collagen fibril assembly knitted silk and collagen sponge scaffold can develop not only structural and functional ligament repair[73]. but also protects articular cartilage and meniscus from degeneration[74].

Collagen

Some researchers have invented a scaffold which is three dimensional and made of type I collagen[75]. This collagen is extracted from bovine submucosa and intestine or rat tails. It should be treated to separate foreign antigens, to halt the degradation rate cross linking should be done, and to develop its mechanical strength[76]. Tensile strength of collagen fibers can be increased by decreasing the fiber diameter. Another study a collagenous ACL prostheses were developed by embodying a 225 reconstitute collagen type I fibers in type I collagen matrix and placing polymethymethacrylate bone fixation plugs on the ends[77].

Synthetic Polymers

A polymer mesh of polycaprolactone and polyester urethane urea was fabricated to induce ligament regeneration[78]. Polycaprolactone and chitosan blends has been invented for the production of collagen in ligament regeneration[79]. A composite scaffold of knitted structure and aligned PLCL microfibers were invented for ligament regeneration[17]. Efficacy of UHMWPCL over normal PCL, UHMWPCL degrades more slowly, allowing the fibres to grow longer[80].

PGA and PLLA are the two main synthetic polymers[81]. Poly-lactic-co-gyclide (PLGA) and poly-L-lactic (PLLA) are isoforms of these products. This polymers have a wide range of physical and mechanical properties appropriate for tissue integration when it degrades by hydrolysis or enzymatic activity[82]. Twisted fiber architectures composed of silk matrix and PLA fibres can promote ligament tissue regeneration. PGA has the highest strength Compared to PLLA and PLAGA but it degrades more quickly[83]. Sahoo et al. studied that a novel biodegradable nano microfibrous PLGA scaffold had been invented in order to provide a large surface area for cell attachment[84].

Table 2: Advantages and disadvantages of some common biomaterials

| Biomaterial | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen[85-87] | Biocompatible, major component of native ACL | Lacks mechanical strength, immunogenic |

| Hyaluronic acid[88] | Biocompatible ECM component; can be in sponge or hydrogel form | Lacks mechanical strength. |

| Silk[89] | Good tensile strength | Limited cell adhesion. Sericin coating is immunogenic. |

| Alginate[90-91] | Biocompatible, can encapsulate cells, can be in sponge or hydrogel form | Lacks mechanical strength. |

| Chitosan[92-93] | Biocompatible, chemically modifiable | Limited cell adhesion and lacks mechanical strength |

| PGA[94] | Common FDA-approved suture material. | Rapid degradation and loss of mechanical Strength, biologically inert. Acidic degradation By product |

| PDS[95] | Common FDA-approved suture material Easily manufactured into different forms. | Rapid loss of mechanical strength. |

| PLGA[96] | Degradation rate can be changed. Easily manufactured. | Biologically inert, Acidic degradation by product |

| PCL[97] | Common FDA approved suture material, Easily manufactured. | Very slow degradation rate, biologically inert. |

| PLLA[98] | Slow degradation rate, better cell adhesion than PLA or PLGA. Easily manufactured. | Biologically inert, Acidic degradation by |

| PET[99] | Nondegradable, biocompatible, mechanically strong properties | Insufficient hydrophilicity and bioactivity |

ACL Reconstruction by Using Prostheses

Stryker/Dacron ligament

Between 1989[100] and 1997[101] ten case series published to report the use of Stryker/Dacron ligament for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction[87-91,101-105]. The graft is composed of a central core of four tightly woven tapes encased by a sheath of loosely woven velour, it was hoped that it can improve functional scoring and objective stability with long term follow up but there was a high objective failure rate[92,106]. H. Pinar studied that mechanical characteristics of a knitted 8mm Dacron tube was used as augmentation for patellar tendon strips was analysed and compared with LAD tendon strips, composite was stiffer than LAD[93,107].

ABC Surgicraft

The surgicraft ABC prosthetic ACL has carbon and polyester fibres combined in a partial braid by a zigzag assembly,which possess the mechanical characteristics suitable for ACL replacement[54]. but after surgery it appears to be associated with high failure rate[94,108].

Guidoin et al. published that ABC surgicraft prostheses were well encapsulated by collagenous tissue which penetrated to the core of the ligament but after surgery it appears to be associated with high failure rate. The graft was implanted by two different techniques and studies have shown that there is no significant difference between two graft replacements[95,109]. synovitis and stiffness problem was noticed due to particulate debris[96,97,110,111].

Gore-Tex

A synthetic ligament was invented by W.L. Gore and associates in the 1970s[98,112]. Gore-Tex/autogenous composite graft was developed to combine the advantages of the immediate stability of a synthetic with the long term stability of an autograft[99,113]. The Gore-Tex ligament is made of poly tetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) or Teflon fibre in a single stranded braided chain. Inert nature and high tensile strength are main reasons behind its application as a graft material[100-102, 114-116] developed a three dimensional expanded (e PTFE) poly (lactic co glycolic acid) PLGA scaffold for tissue engineering. The main drawback was the nondegradable behaviour of e PTFE[103,117].

Leeds-Keio ligament

Leeds-Keio ligament (LK) open weave polyester ligament (neoligaments Ltd, UK) is a synthetic ligament substitute for ACL reconstruction which has been widely used in the 1980s and early 1990s[104,118]. It’s strength, relatively low stiffness, and biological inertness are the main attraction for choosing it as an ACL replacement[105,119]. The type LK ligament is designed to act as a scaffold for capturing by soft tissue, which will mature and grow fibres capable of sharing load with the scaffold. ACL reconstruction augmented with LK.

LARS ligament

This synthetic non-absorbable ligament is made of terepthalic polyethylene polyester fibres and due to its immediate great stability, strong mechanical properties[107,121], reduced rehabilitation time and, quicker return to pre-injury function LARS ligament became one of the most preferable choice for ACL reconstruction[108,122]. Several research was undertaken to understand the work efficiency of this graft as ACL substitute but due to its insufficient surface hydrophilicity and bioactivity it loses its attraction as an synthetic ACL graft after implantation[109,110,123,124]. Different types of materials have been used to alter the surface of PET[111,125] grafts beneficial to increase their surface bioactivity, including polymers and bio ceramics[112,113,126,127]. LARS also incorporated with hamstring tendon graft for better performance[114,128].

KLAD

In the 1970’s John Kennedy of Canada was developed the Ligament Augmentation Device for the augmentation of Marshall/McIntosh reconstruction. LAD is a braided polypropylene fabricated as a continuous fibre and heat sealed at both ends to avoid failure[115,116,129,130]. The LAD is meant to protect the biological graft during the endangered phase when the graft undergoes a phase of degeneration and loss of strength before being incorporated[117,130]. Splitting of polypropylene braid augmented can cause foreign body synovitis[118,119,131,132].

UHMWPE/PHP

Food and Drug Administration approved the proplast device in 1973, and by the mid-1970s, the original Kennedy prosthesis made from Hercules 1900 ultra-high-molecular weight polyethylene also known as high-performance polyethylene became commercially available as (i) Braided PHP ligament (ii) Raschel or knitted PHP ligament[120,132].

Guidoin et al. studied that ligaments were condensed by thick collagenous tissue which partly penetrated the outer layers of the prosthesis in braided structure. This collagen penetration caused an expansion and separation of the multifilament yarns into individual fibers but for knitted structure the devices were encapsulated by thin collagenous tissue without any significant infiltration into the structure. A hollow braided construct was designed where a core of parallel PVA cord is wrapped by a diamond braided structure of UHMWPE threads to develop the better mechanical performance[121,135].

Table 3: Some commercial ACL reconstruction materials

| Commercial name | Manufacturer | Class | Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stryker | Stryker, Michigan, USA | Woven/Knitted | PET |

| ABC Surgicraft | Surgicraft,Redditch, UK | Braided | PET/PET-C |

| Gore-Tex | WL core &Associates, Arizona, USA | Braided | PTFE |

| Leeds-Keio | Neoligamnet Ltd, UK | Woven | PET |

| LARS | Structural instruments and Devices, Arc-sur-Tille, France. | Loose/Knitted | PET |

| Kennedy-LAD | 3M, Minnesota, USA | Braided | POLYPROPYLENE |

| Proflex | Protek, France | Braided | PET |

| Lygeron | Orthogroup, France | Woven | PET |

| Ligastic | Orthomed, France | Knitted | PET |

| Ligaid | Porth-Aid, France | Twisted | PAA |

| Raschel | Cendis medical, France | Knitted | UHMWPE |

| Braided PHP | Cendis Medical, France | Braided | UHMWPE |

Biomaterials for Graft Modification

Chitosan a naturally derived polysaccharide has been used for modification of synthetic graft[122,123,136,137]. Chitosan-Hyaluronic composite had a positive effect for promoting new bone formation at the graft bone interface[124,125,138,139] because of its biodegradability, biocompatibility, anti-infectional activity, and property to accelerate wound healing[127,128,140,141].

C.Vaquette et al studied that Polystyrene sodium sulfonate can improve the osteointegration and that’s why it has been used for surface modification of synthetic graft[128,142].

Bioactive glass stimulates the angiogenic growth factors[129,130,143,144]. Bioactive glasses are a unique compositional range of dense, amorphous calcium, sodium phosphosilicate (CSPS) materials that develop strong chemical bonds with the collagen of living tissues[131,132,145,146]. The composition of 45S5 bio glass is 45% SiO2, 24.5% CaO, 24.5% Na2O, and 6% P2O5[130,133,143,147]. Bioactive glasses when come in contact with simulated body fluid it can dissolve slowly. Some reactions take place on the surface of the glass[134,148].

i) Ions are released due to the ion exchange between the solution and surface of the glass but other components of the glass remain intact[135,149].

ii) H+ ions attacked the silica network as a result Si-o-Si bond breaks down and new Si OH and Si (OH)4 groups are formed at the surface of the glass.

iii) A soluble porous silica rich layer formed on the surface of the glass due to the condensation and re polymerization.

iv) A calcium phosphate rich layer formed on the of the Si rich layer due to the migration of Ca2 + and (PO4)3- ions

v) Polycrystalline apatite layer formed on the surface of the bio glass.

Collagen fibres can attach to the surface of the bioactive glass. Pure silica rich layer can induce precipitation of HCA layer. Interactions between bio glass and collagen fibres occur and it gets stronger when HCA precipitation increases[131,145]. Surface modifier plays an important role to help osteogenesis and bone anchorage of synthetic graft[150].

Conclusion

In summary, all research based on ligament regeneration are useful for clinical practise, allograft, autograft and even though synthetic graft everything has some beneficial characteristics to recover anterior cruciate ligament. All the studies which have been mentioned above are essential for clinical practise of ligament to design a new implant for anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Tissue engineering has advanced a lot nowadays. Besides allograft and autograft synthetic grafts are the pioneer of recent ligament regeneration although have some disadvantages. Lots of promising work is going on to mitigate the problem of synthetic ligament design. Ligament regeneration is a challenging work due to the complex structure of ACL ligament. To date, there is no standard gold model for ACL reconstruction but we expect that upcoming design structure will fulfil all the requirements for ACL reconstruction.

References

- 1. Hasegawa, A., Otsuki, S., Pauli, C., et al. Anterior cruciate ligament changes in the human knee joint in aging and osteoarthritis. (2012) Arthritis Rheum 64(3): 696-704.

- 2. Pujol, N., Colombet, P., Cucurulo, T., et al. Natural history of partial anterior cruciate ligament tears: A systematic literature review. (2012) Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 98(8): S160-S164.

- 3. Shelbourne, K.D., Urch, S.E. Treatment Approach to Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. (2009) Oper Tech Sports Med 17(1): 24-31.

- 4. Laurencin, C.T, Freeman, J.W. Ligament tissue engineering: An evolutionary materials science approach. (2005) Biomaterials 26(36): 7530-7536.

- 5. Loudon, J.K., Jenkins, W., Loudon, K.L. The relationship between static posture and ACL injury in female athletes. (1996) J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 24(2): 91-97.

- 6. Laurencin, C.T., Ambrosioa, M., Borden, M.D., et al. Tissue engineering: orthopedic applications. (1999) Annu Rev Biomed Eng 1:19-46.

- 7. Iosifidis, M.I., Tsarouhas, A. Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Rehabilitation. (2012) Sports Injuries 421-430.

- 8. Jackson, D.W., Grood, E.S., Goldstein, J.D., et al. A comparison of patellar tendon autograft and allograft used for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the goat model. (1992) Am J Sports Med 21: 176-185.

- 9. Legnani, C., Ventura, A., Terzaghi, C., et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with synthetic grafts. A review of literature. (2010) Int Orthop 34: 465-471.

- 10. Chang, P-C., Liu, B-Y., Liu, C-M., et al. Bone tissue engineering with novel rhBMP2-PLLA composite scaffolds. (2007) J Biomed Mater Res A 81: 771-780.

- 11. Caves, J.M., Kumar, V. A., Wen, J., et al. Fibrillogenesis in continuously spun synthetic collagen fiber. (2010) J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 93(1): 24-38.

- 12. Chambat, P. ACL tear. (2013) Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 99: 43-52.

- 13. Zantop, T., Petersen, W., Sekiya, J.K., et al. Anterior cruciate ligament anatomy and function relating to anatomical reconstruction. (2006) Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 14(10): 982-992.

- 14. Butler, D.L. Kappa Delta Award paper. Anterior cruciate ligament: its normal response and replacement. (1989) J Orthop Res 7(50): 910-921.

- 15. Ventura, A., Terzaghi, C., Legnani, C., et al. Synthetic grafts for anterior cruciate ligament rupture: 19-year outcome study. (2010) Knee 17(2): 108-113.

- 16. Woo S.L.Y., Adams, J., Daniel., et al. Knee Ligaments: Structure , Function , Injury , and Repair. (2015).

- 17. Vaquette, C., Kahn, C., Frochot, C., et al. Aligned poly (L-lactic-co-e-caprolactone) electrospun microfibers and knitted structure: A novel composite scaffold for ligament tissue engineering. (2010) J Biomed Mater Res - Part A 94(4): 1270-1282.

- 18. Prins, M. The Lachman test is the most sensitive and the pivot shift the most specific test for the diagnosis of ACL rupture. (2006) Aust J Physiother 52(1): 66.

- 19. Monajem, A. Functional Anterior Anatomy of the Ligament. (1991) J Bone Jt Surg 73: 260-267.

- 20. Foster, T.E., Wolfe, B.L., Ryan, S., et al. Does the Graft Source Really Matter in the Outcome of Patients Undergoing Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction? An Evaluation of Autograft Versus Allograft Reconstruction Results: A Systematic Review. (2010) Am J Sports Med 38(1): 189-199.

- 21. Chehab, E.L., Flik, K.R., Vidal, A.F., et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using achilles tendon allograft: an assessment of outcome for patients age 30 years and older. (2011) HSS J 7(1): 44-51.

- 22. Bak, K., Jørgensen, U., Ekstrand, J., et al. Reconstruction of anterior cruciate ligament deficient knees in soccer players with an iliotibial band autograft. A prospective study of 132 reconstructed knees followed for 4 (2-7) years. (2001) Scand J Med Sci Sports 11(1): 16-22.

- 23. Steadman, J.R., Matheny, M., Briggs, K.K., et al Patient-Centered Outcomes and Revision Rate in Patients Undergoing ACL Reconstruction Using Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone Autograft Compared With Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone Allograft: A Matched Case-Control Study. (2015) Arthroscopy 31(12): 2320-2326

- 24. Beard, D.J., Anderson, J.L., Davies, S., et al. Hamstrings vs. patella tendon for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A randomised controlled trial. (2001) Knee 8(1): 45-50.

- 25. Graft, Q.H. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Using Quadruple Hamstring. (1999) 9(4): 264-272.

- 26. Biau, D.J., Tournoux, C., Katsahian, S., et al. Bone-patellar tendon-bone autografts versus hamstring autografts for reconstruction of anterior cruciate ligament: meta-analysis. (2006) BMJ 332(7548): 995-1001.

- 27. Adachi, N., Ochi, M., Uchio, Y., et al. Harvesting hamstring tendons for ACL reconstruction influences postoperative hamstring muscle performance. (2003) Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 123(9): 460-465.

- 28. Ageberg, E., Roos, H.P., Silbernagel, K.G., et al. Knee extension and flexion muscle power after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon graft or hamstring tendons graft: A cross-sectional comparison 3 years post surgery. (2009) Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 17(2): 162-169.

- 29. Yip K, Y.E., Chan, W.L., Lie W, H.C., et al. Isokinetic Quadriceps and Hamstring Muscle Strength After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Comparison Between Single-bundle and Double-bundle Reconstruction. (2013) J Orthop Trauma Rehabil 17(2): 71-76.

- 30. Elmlinger, B.S., Nyland, J.A., Tillett, E.D. Knee Flexor Function 2 Years after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction With Semitendinosus-Gracilis Autografts. (2006) Arthroscopy 22(6): 650-655.

- 31. Armour, T., Forwell, L., Litchfield, R., et al. Isokinetic Evaluation of Internal/External Tibial Rotation Strength after the Use of Hamstring Tendons for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. (2004) Am J Sports Med 32(7): 1639-1643.

- 32. Lautamies, R., Harilainen, A., Kettunen, J., et al. Isokinetic quadriceps and hamstring muscle strength and knee function 5 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Comparison between bone-patellar tendon-bone and hamstring tendon autografts. (2008) Knee Surgery Sport Traumatol Arthrosc 16(11): 1009-1016.

- 33. Stäubli, H.U., Schatzmann, L., Brunner, P., et al. Mechanical tensile properties of the quadriceps tendon and patellar ligament in young adults. (1999) Am J Sports Med 27(1): 27-34.

- 34. Howe, J.G., Johnson, R.J., Kaplan, M.J., et al. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction using Quadriceps Patellar Tendon graft Part.1. Long-term Follow-Up. (1991) Am J Sports Med 19(5): 447-457.

- 35. Victor, J., Bellemans, J., Witvrouw, E., et al. Graft selection in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction--prospective analysis of patellar tendon autografts compared with allografts. (1997) Int Orthop 21(2): 93-97.

- 36. Kapoor, B., Clement, D.J., Kirkley, A., et al. Current practice in the management of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the United Kingdom. (2004) Br J Sports Med 38(5): 542-544.

- 37. Marx, R.G., Jones, E.C., Angel, M., et al. Beliefs and attitudes of members of the American Academy of orthopaedic surgeons regarding the treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injury. (2003) Arthroscopy 19(7): 762-770.

- 38. Cohen, S.B., Sekiya, J.K. Allograft safety in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. (2007) Clin Sports Med 26(4): 597-605.

- 39. Qu, J., Thoreson, A.R., An, K.N., et al. What is the best candidate allograft for ACL reconstruction? An in vitro mechanical and histologic study in a canine model. (2015) J Biomech 48(10): 1811-1816.

- 40. Wei, J., Yang, H.B., Qin, J.B., et al A meta-analysis of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autograft compared with nonirradiated allograft. (2015) Knee 22(5): 372-379.

- 41. Linn, R.M., Fischer, D., Smith, J.P., et al. Achilles tendon allograft reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. (1993) Am J Sports Med 21(6): 825-831.

- 42. Shino, K., Nakata, K., Horibe, S., et al. Quantitative evaluation after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Allograft versus autograft. (1993) Am J Sports Med 21(4): 609-616.

- 43. Haut Donahue, T.L., Howell, S.M., Hull, M.L., et al. A biomechanical evaluation of anterior and posterior tibialis tendons as suitable single-loop anterior cruciate ligament grafts. (2002) Arthroscopy 18(6): 589-597.

- 44. Pearsall, A.W., Hollis, J.M,, Russell, G.V., et al. A Biomechanical Comparison of three Lower Extremity Tendons for Ligamentous Reconstruction about the Knee. (2003) Arthroscopy 19(10): 1091-1096.

- 45. Carter, T., Rabago, M. Allograft ACL Reconstruction in Patients Under 25 Years of Age. (2014) Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg 30(6): e9.

- 46. Fu, F.H., Bennett, C.H., Lattermann, C., et al. Current Trends in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Part 1 : Biology and Biomechanics of Reconstruction (1999) Am J Sports Med 27(6): 821-830.

- 47. Anderson, A.F., Snyder, R.B., Lipscomb, A.B. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. A Prospective Randomized Study of Three Surgical Methods. (2001) Am J Sports Med 29(3): 272-279.

- 48. Jansson, K.A., Linko, E., Sandelin, J., et al. A Prospective Randomized Study of Patellar versus Hamstring Tendon Autografts for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. (2003) Am J Sports Med 31(1): 12-18.

- 49. Sherman, O.H., Banffy, M,B. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: which graft is best? (2004) Arthroscopy 20(9): 974-980.

- 50. Leong, N.L., Petrigliano, F.A., McAllister, D.R. Current tissue engineering strategies in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. (2014) J Biomed Mater Res A 102(5): 1614-1624.

- 51. Craig L. iom anics of Synthetic Augmentation o en. (1994) 15: 23-27.

- 52. MATERIALS NEW.

- 53. Sorsa, T., Noponen, J., Kelloma, M., et al. Soft tissue reactions to bioactive glass 13-93 combined with chitosan. (2007) J Biomed Mater Res A 83(2): 530-537.

- 54. Potluri, P., Cooke, W., Lamia, A., et al. Designing the Carbon-Polyester Braids for Ligaments. (2003) Journal of Textile and Apparel Technology and Management 3(2): 1-12.

- 55. Cooper, J.A., Lu, H.H., Ko, F.K., et al. Fiber-based tissue-engineered scaffold for ligament replacement: Design considerations and in vitro evaluation. (2005) Biomaterials 26(13): 1523-1532.

- 56. Ge, Z., Goh, J.C., Lee, E.H. Selection of cell source for ligament tissue engineering. (2005) Cell Transplant 14(8): 573-583.

- 57. Chen, G., Kawazoe, N. Preparation of Polymer-Based Porous Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. (2016) Characterisation and Design of Tissue Scaffolds, Elsevier 105-125.

- 58. Brekke, J.H., Toth, J.M. Principles of Tissue Engineering Applied to Programmable Osteogenesis. (1998) J Biomed Mater Res 43(4): 380-398.

- 59. Ge, Z., Yang, F., Goh, J.C., et al. Review Biomaterials and scaffolds for ligament tissue engineering. (2006) J Biomed Mater Res 77(3): 639-652.

- 60. Massia, S.P., Hubbell, J. A. Covalently attached GRGD on polymer surfaces promotes biospecific adhesion of mammalian cells. (1990) Ann N Y Acad Sci 589: 261-270.

- 61. Park, K., Cooper, S.L., Mosher, D.F. Acute surface-induced thrombosis in the canine ex vivo model: Importance of protein composition of the initial monolayer and platelet activation. (1986) J Biomed Mater Res 20(5): 589-612.

- 62. Vats, A., Tolley, N.S., Polak, J.M., et al. Scaffolds and biomaterials for tissue engineering: A review of clinical applications. (2003) Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 28(3): 165-172.

- 63. Chen, Q.Z., Thompson, I.D., Boccaccini, A.R. 45S5 Bioglass®-derived glass–ceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. (2006) Biomaterials 27(11): 2414-2425.

- 64. Zhang, Q., Yan, S.Q., Li, M.Z. Porous Materials Based on Bombyx Mori Silk Fibroin. (2010) J Fiber Bioeng Informatics 3(1): 1-8.

- 65. Li, H., Wu, C., Chang, J., et al. Functional Polyethylene Terephthalate with Nanometer-Sized Bioactive Glass Coatings Stimulating In Vitro and In Vivo Osseointegration for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. (2014) Adv Mater Interfaces 1(5).

- 66. Panas, E., Gatt, J., Dunn, M.G. In Vitro Analysis of a Tissue-Engineered Anterior Cruciate Ligament Scaffold. (2009) IEEE 35th Annual Northeast Bioengineering Conference. 3-4.

- 67. Inouye, K., Kurokawa, M., Nishikawa, S., et al. Use of Bombyx mori silk fibroin as a substratum for cultivation of animal cells. (1998) Journal of Biochemical and Biophysical Methods 37: 159-164.

- 68. Greenwald, D., Shumway, S., Albear, P., et al. suture materials.

- 69. Altman, G.H., Horan, R.L., Lu, H.H., et al. Silk matrix for tissue engineered anterior cruciate ligaments. (2002) Biomaterials 23(20): 4131-4141.

- 70. Farè, S., Torricelli, P., Giavaresi, G., et al. In vitro study on silk fibroin textile structure for anterior cruciate ligament regeneration. (2013) Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 33(7): 3601-3608.

- 71. Li, X., Snedeker, J.G. Wired silk architectures provide a biomimetic ACL tissue engineering scaffold. (2013) J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 22: 30-40.

- 72. Li, X., He, J., Bian, W., et al. A novel silk-TCP-PEEK construct for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: an off-the shelf alternative to a bone-tendon-bone autograft. (2014) Biofabrication 6(1): 015010.

- 73. Chen, X., Qi, Y-Y., Wang, L-L., et al. Ligament regeneration using a knitted silk scaffold combined with collagen matrix. (2008) Biomaterials 29(27): 3683-3692.

- 74. Chen, J., Heng, B.C., Shen , W., et al. Long-term effects of knitted silk – collagen sponge scaffold on anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and osteoarthritis prevention. (2014) Biomaterials 35(28): 8154-8163.

- 75. Robayo, L.M., Moulin, V.J., Tremblay, P., et al. New ligament healing model based on tissue-engineered collagen scaffolds. (2011) Wound Repair Regen 19(1): 38-48.

- 76. Laflamme, M., Lamontagne, J., Guidoin, R. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Prostheses Using Biotextiles. (2015) Biomedical Textiles for Orthopaedic and Surgical Applications, Elsevier Ltd. 145-190.

- 77. Dunn, M.G., Avasarala, P.N., Zawadsky, J.P., et al. Optimization of extruded collagen fibers for ACL reconstruction. (1993) J Biomed Mater Res 27(12): 1545-1552.

- 78. Samavedi, S., Olsen, H.C., Guelcher, S.A., et al. Fabrication of a model continuously graded co-electrospun mesh for regeneration of the ligament-bone interface. (2011) Acta Biomater 7(12): 4131-4138.

- 79. Shao, H.J., Lee, Y.T., Chen, C.S., et al. Modulation of gene expression and collagen production of anterior cruciate ligament cells through cell shape changes on polycaprolactone/chitosan blends. (2010) Biomaterials 31(17): 4695-4705.

- 80. Leong, N.L., Kabir, N., Arshi, A., et al. Use of ultra-high molecular weight polycaprolactone scaffolds for ACL reconstruction. (2015) J Orthop Res

- 81. Athanasiou, K. A., Niederauer, G.G., Agrawal, C.M. Sterilization, toxicity, biocompatibility and clinical applications of polylactic acid/polyglycolic acid copolymers. (1996) Biomaterials 17(2): 93-102.

- 82. Athanasiou, K.A., Agrawal, C.M., Barber, F.A., et al. Orthopaedic applications for PLA-PGA biodegradable polymers. (1998) Arthroscopy 14(7): 726-737.

- 83. Lu, H.H., Cooper, J. A., Manuel, S., et al. Anterior cruciate ligament regeneration using braided biodegradable scaffolds: in vitro optimization studies. (2005) Biomaterials 26(23): 4805-4816.

- 84. Sahoo, S., Ouyang, H., Tay, T.E., et al. Characterization of a Novel Polymeric Scaffold for Potential Application in Tendon / Ligament. (2004) Tissue Engineering 12(1): 1-9.

- 85. Dunn, M.G., Liesch, J.B., Tiku, M.L., et al. Development of fibroblast-seeded

- 86. Bellincampi, L.D., Closkey, R.F., Prasad, R., et al. Viability of fibroblast-seeded ligament analogs after autogenous implantation. (1998) J Orthop Res 16 (4): 414–420.

- 87. Goulet, F. Tendons and Ligaments. In: Lanza R, Langer R, Vacanti J, editors. (2011) Principles of Tissue Engineering 911–9914.

- 88. Cristino, S., Grassi, F., Tonguzzi, S., et al. Analysis of mesenchymal stem cells grown on a three dimensional HYAFF-11 based prototype ligament scaffold. (2005) J Biomed Master Res A 73(3): 275-283.

- 89. Chen, J., Altman, G.H., Karageorgiou, V., et al. Human bone marrow stromal cell and ligament fibroblast responses on RGD-modified silk fibers. (2003) J Biomed Mater Res A 67(2): 559–570.

- 90. Masuko, T., Iwasaki, N., Yamane, S., et al. Chitosan-RGDSGGC conjugate as scaffold material for muscoskeletal tissue engineering. Biomaterials (2005) 26(26): 5339-5347.

- 91. Majima, T., Funakoshi,T., Isawaki, N., et al. Alginate and chitosan polyion complex hybrid fibers for scaffold in ligament and tendon tissue engineering. (2005) J Orthop sci 10(3): 302-307.

- 92. Hansson, A., Hashom, N., Falson, F., et al. In vitro evaluation of an RGD-functionalized chitosan derivative for enhanced cell adhesion. (2012) Carbohydr Polym 90(4): 1494-1500.

- 93. Shao, H.J., Chen, C.S., Lee, Y.T., et al. The phenotypic responses of human anterior cruciate ligament cells cultured on poly(epsilon-caprolactone) and chitosan. (2010) J Biomed Mater Res A 93(4): 1297-1305.

- 94. Lin,V.S., Lee, M.C., O’Neal, S., et al. Ligament tissue engineering using synthetic biodegradable fiber scaffolds. (1999) Tissue Eng 5(5): 443-452.

- 95. Buma, P., Kok, H.J., Blankevoort, L., et al. Augmentation in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction-a histological and biomechanical study on goats. (2004) Int Orthop 28(2): 91-96.

- 96. James, R., Toti, U.S., Laurencin, C.T., et al. Elecrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for engineering soft connective tissues. (2011) Methods Mol Biol 726: 243-258.

- 97. Peach, M.S., Kumbar, S.G., James, R., et al. Design and optimization of polyphosphazene functionalized fiber matrices for soft tissue regeneration. (2012) J Biomed Nanotechnol 8(1): 107–124.

- 98. Lu, H.H., Cooper, J.A., Manuel, S., et al. Anterior cruciate ligament regeneration using braided biodegradable scaffolds: In vitro optimization studies. (2005) Biomaterials 26(23): 4805-4816.

- 99. Alexis, V., John, C., Barrett, G.R., et al. A multicenter study on the results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using a Dacron ligament prosthesis in “salvage” cases. (1989) Am J Sports Med 17(3): 380-385.

- 100. Maletius, W. Long-term Results of Anterior Ligament Reconstruction with Prosthesis Cruciate a Dacron the Frequency of Osteoarthritis after Seven to Eleven Years. (1997) Am J Sports Med 25(3): 288-293.

- 101. Klein, W., Jensen, K. Synovitis and Artificial Ligaments. (1992) Arthoscopy 8(l):116-124.

- 102. Andersen, H.N., Bruun, C., Søndergård-Petersen, P.E. Reconstruction of chronic insufficient anterior cruciate ligament in the knee using a synthetic Dacron prosthesis. A prospective study of 57 cases. (1992) Am J Sports Med 20(1): 20-23.

- 103. Barrett, G.R., Line, L.L., Shelton, W.R., et al. The Dacron ligament prosthesis in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A four-year review. (1993) Am J Sports Med 21(3): 367-373.

- 104. Wredmark, T., Engström, B. Five-year results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with the Stryker Dacron high-strength ligament. (1993) Knee Surgery Sport Traumatol Arthrosc 1(2): 71-75.

- 105. Wilk, R.M., Richmond, J.C. Dacron ligament reconstruction for chronic anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency. (1993) Am J Sports Med 21(3): 374-379; discussion 379-380.

- 106. Richmond, J.C., Manseau, C.J., Patz, R., et al. Anterior cruciate reconstruction using a Dacron ligament prosthesis. A long-term study. (1992) Am J Sports Med 20(1): 24-28.

- 107. Pinar, H., Gillquist, J. Dacron Augmentation of a Free Patellar Tendon Graft : A Biomechanical Study. (1989) Anthroscopy 5(4): 328-330.

- 108. World Physical Therapy (2007) 93(supp1): S1-S802.

- 109. Beard, D.J., Kyberd, P.J., Fergusson, C.M., et al. Proprioception after rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament. An objective indication of the need for surgery? (1993) J Bone Joint Surg Br 75(2): 311-315.

- 110. Chardouvelis, C., Kouzoupis, A., Dermon, A., et al. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament using the polyester ABC ligament scaffold. (2006) J Bone Joint Surg Br 88(7): 893-899.

- 111. Amis, A.A., Kempson, S.A., Campbell, J.R., et al. Anterior cruciate ligament replacement. Biocompatibility and biomechanics of polyester and carbon fibre in rabbits. (1988) J Bone Joint Surgery Br 70(4): 628-634.

- 112. Johnson, D. Gore-tex synthetic ligament. (1995) Oper Tech Sports Med 3(3): 173-176.

- 113. Davldson, J.F.J., Collins, H.R., Campbell, E.D. Composite Gore-Tex and Autogenous Semitendinosus Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction : Long-Term Results and Historical Review. (1995) Oper Tech Sports Med 3(3): 177-181.

- 114. Virk, S.S., Kocher, M.S. Adoption of new technology in sports medicine: Case studies of the gore-tex prosthetic ligament and of thermal capsulorrhaphy. (2011) Arthroscopy 27(1): 113-121.

- 115. Thomson, L.A., Law, F.C., James, K.H., et al. Biocompatibility of particles of GORE-TEX cruciate ligament prosthesis: an investigation both in vitro and in vivo. (1991) Biomaterials 12(8): 781-785.

- 116. Shao, H.J., Chen, C.S., Lee, I.C., et al. Designing a three-dimensional expanded polytetrafluoroethylene-poly(lactic- co-glycolic acid) scaffold for tissue engineering. (2009) Artif Organs 33(4): 309-317.

- 117. Muller-Mai, C.M., Gross, U.M. Histological and ultrastructural observations at the interface of expanded polytetrafluorethylene anterior cruciate ligament implants. (1991) J Appl Biomater 2(1): 29-35.

- 118. Laflamme, M., Lamontagne, J., Guidoin, R. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Prostheses Using Biotextiles. (2013) Anterior cruciate ligament prostheses using biotextiles, Elsevier Ltd 590-639.

- 119. Macnicol, M.F., Penny, I.D., Sheppard, L. Early Results of Leeds-Keio anterior cruciate Replacement Ligament. (1991) J Bone Joint Surg Br 73(3): 377-380.

- 120. Ohtani, T. Reconstruction the of the the Apparatus Ligament of Knee Leeds-Keio. (1994) J Bone Joint Surg Br 76(2): 200-203.

- 121. Ranger, P., Renaud, A., Phan, P., et al. Evaluation of reconstructive surgery using artificial ligaments in 71 acute knee dislocations. (2011) Int Orthop 35(10): 1477-1482.

- 122. Mulford, J.S., Chen, D. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review of polyethylene terephthalate grafts. (2011) ANZ J Surg 81(11): 785-789.

- 123. Li, H., Ge, Y., Wu, Y., et al. Hydroxyapatite coating enhances polyethylene terephthalate artificial ligament graft osseointegration in the bone tunnel. (2011) Int Orthop 35(10): 1561-1567.

- 124. Dabirrahmani, D., ChristopherHogg, M., Walker, P., et al. Comparison of isometric and anatomical graft placement in synthetic ACL reconstructions: a pilot study. (2013) Comput Biol Med 43(12): 2287-2296.

- 125. Giol, E.D., Schaubroeck, D., Kersemans, K., et al. Bio-inspired surface modification of PET for cardiovascular applications: case study of gelatin. (2015) Colloids Surf Bio Biointerfaces 134: 113-121

- 126. Yang, J., Jiang, J., Li, Y., et al. A new strategy to enhance artificial ligament graft osseointegration in the bone tunnel using hydroxypropylcellulose. (2013) Int Orthop 37(3): 515-521.

- 127. Sambasivarao,S. V. NIH Public Access. (2013) 18(29): 1199-1216.

- 128. Hamido, F., Al Harran, H., Al Misfer, A. R., et al. Augmented short undersized hamstring tendon graft with LARS® artificial ligament versus four-strand hamstring tendon in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: preliminary results. (2015) Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 101(5): 535-538.

- 129. Hunter, R.E. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstructuon with a composite graft bone-patellar tendon-bone/ligament augmentation device. (1995) Oper Tech Sports Med 3(3): 5.

- 130. Hospital, K.C., Thuresson, P. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with the patellar tendon - augmentation or not? Scand J Med Sci Sports: 247-254.

- 131. Kumar, K., Maffulli, N. The ligament augmentation device: an historical perspective. (1999) Arthroscopy 15(4): 422-432.

- 132. Kim, S-J., Jeong, J-H., Ko, Y-G. Synovitic cyclops syndrome caused by a Kennedy ligament augmentation device. (2003) Arthroscopy 19(4): E38.

- 133. Dürselen, L., Häfner, M., Ignatius, A., et al. Biological response to a new composite polymer augmentation device used for cruciate ligament reconstruction. (2006) J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater 76(2): 265-272.

- 134. Guidoin, M-F., Marois, Y., Bejui, J., et al. Analysis of retrieved polymer fiber based replacements for the ACL. (2000) Biomaterials 21(23): 2461-2474.

- 135. Bach, J.S., Detrez, F., Cherkaoui,M., et al. Hydrogel fibers for ACL prosthesis: Design and mechanical evaluation of PVA and PVA/UHMWPE fiber constructs. (2013) J Biomech 46(8): 1463-1470.

- 136. Park, H., Choi, B., Hu, J., et al. Injectable chitosan hyaluronic acid hydrogels for cartilage tissue engineering. (2013) Acta Biomaterialia 9(1): 4779-4786.

- 137. Tan, H., Chu, C.R., Payne, K. A., et al. Injectable in situ forming biodegradable chitosan-hyaluronic acid based hydrogels for cartilage tissue engineering. (2009) Biomaterials 30(13): 2499-2506.

- 138. Correia, C.R., Moreira-Teixeira, LS, Moroni L, et al. Chitosan scaffolds containing hyaluronic acid for cartilage tissue engineering. (2011) Tissue Eng Part C Methods 17(7): 717-730.

- 139. Kojima, K., Okamoto, Y., Kojima, K., et al. Effects of chitin and chitosan on collagen synthesis in wound healing. (2004) J Vet Med Sci 66(12): 1595-1598.

- 140. Minagawa, T., Okamura, Y., Shigemasa, Y., et al. Effects of molecular weight and deacetylation degree of chitin / chitosan on wound healing. (2007) Carbohydrate Polymers 67: 640-644.

- 141. Obara, K., Ishihara, M., Ishizuka, T., et al. Photocrosslinkable chitosan hydrogel containing fibroblast growth factor-2 stimulates wound healing in healing-impaired db/db mice. (2003) Biomaterials 24(20): 3437-3444.

- 142. Vaquette, C., Viateau, V., Guérard, S., et al. The effect of polystyrene sodium sulfonate grafting on polyethylene terephthalate artificial ligaments on invitro mineralisation and invivo bone tissue integration. (2013) Biomaterials 34(29): 7048-7063.

- 143. Day, R.M. Bioactive glass stimulates the secretion of angiogenic growth factors and angiogenesis in vitro. (2005) Tissue Eng 11(5): 768-777.

- 144. Gerhardt, L-C., Boccaccini, A.R. Bioactive Glass and Glass-Ceramic Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. (2010) Materials (Basel) 3(7): 3867-3910.

- 145. Oréfice, R., Hench, L., Brennan, A., et al. Evaluation of the interactions between collagen and the surface of a bioactive glass during in vitro test. (2009) J Biomed Mater Res Part A 90(1): 114-120.

- 146. Wang, Y., Yang, C., Chen, X., et al. Development and Characterization of Novel Biomimetic Composite Scaffolds Based on Bioglass-Collagen-Hyaluronic Acid-Phosphatidylserine for Tissue Engineering Applications. (2006) Macromol Mater Eng 291(3): 254-262.

- 147. Fu, Q., Rahaman, M.N., Fu, H., et al. Silicate, borosilicate, and borate bioactive glass scaffolds with controllable degradation rate for bone tissue engineering applications. I. Preparation and in vitro degradation. (2010) J Biomed Mater Res Part A 95A: 164-171.

- 148. Valerio, P., Pereira, M.M., Goes, A.M., et al. The effect of ionic products from bioactive glass dissolution on osteoblast proliferation and collagen production. (2004) Biomaterials 25(15): 2941-2948.

- 149. Rahaman, M.N., Day, D.E., SonnyBal, B., et al. Bioactive glass in tissue engineering. (2011) Acta Biomater 7(6): 2355-2373.

- 150. Joanna, L., Ryskowska, Monika auguscik,Ann Sheikh, Aldo R.Boccaccini. Biodegradable polymer composite scaffolds containing Bioglass for bone tissue engineering.