Adductor Canal Block for Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Review of the Current Evidence

Neil A. Hanson, Francis V. Salinas

Affiliation

Anesthesiologist, Virginia Mason Medical Center, United States

Corresponding Author

Stanley C. Yuan, Department of Anesthesiology, Virginia Mason Medical Center 1100 9th Avenue, Seattle, Washington, 98101, USA United States,Tel: (206) 223-6980; E-mail: Stanley.yuan@virginiamason.org

Citation

Yuan, S.C., et al. Adductor Canal Block for Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Review of the Current Evidence. (2016) J Anesth Surg 3(2): 199- 207.

Copy rights

© 2016 Yuan, S.C. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Adductor canal block; Total knee replacement; Femoral nerve block

Abstract

The positive impact of regional anesthesia on surgical outcome has continued to evolve. In recent years, the focus of acute pain management strategies following total knee arthroplasty has shifted from femoral nerve block to adductor canal block. We systematically analyzed the safety and efficacy of adductor canal blocks by reviewing 78 peer-reviewed publications, including 13 randomized controlled trials. There are a number of studies supporting the adductor canal nerve block as a viable alternative for postoperative analgesia after total knee arthroplasty. This novel block has been consistently demonstrated to have equivalent analgesic efficacy compared to femoral nerve block, while simultaneously reducing quadriceps weakness significantly less than femoral nerve block, thus facilitating earlier active mobilization. With focus on early rehabilitation, adductor canal block may be considered a contributory factor preventing complications such as deep vein thrombosis and joint rigidity from the lack of early mobilization. These advances could potentially result in a reduction of total length of hospital stay and therefore a reduction in associated health care costs. Based on the current evidence, we recommend that an adductor canal block could replace a femoral nerve block as the primary regional analgesic following total knee arthroplasty.

Introduction

In the United States alone, over 600,000 total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) are performed annually[1]. The estimation for primary TKA surgery is projected to increase to over 3 million per year by 2030 and knee joint revision procedures are estimated to increase by 600% between 2005 and 2030[2]. While the per capita number of primary TKA surgeries has doubled from 31 to 62 per 10,000, the length of hospitalization stay has decreased drastically[3]. Such a reduction in length of hospitalization may be due to a combination of less invasive surgical approaches, widespread implementation of enhanced recovery clinical pathways (“fast-track” programs), and novel perioperative analgesic techniques[4,5].

Conventional systemic opioid therapy has previously been the primary modality to control pain after TKA. However, post-operative analgesia has evolved over the past decade due to perioperative multimodal medications[6-8], local infiltration analgesia[9], and the advancement of regional anesthetic techniques. The focus of peripheral nerve blocks has shifted the acute pain management strategies following TKA from continuous lumbar epidural analgesia[10], to single injection or continuous Femoral Nerve Block (FNB)[11], and more recently, to the Adductor Canal Block (ACB)[12].

Anatomical considerations

The adductor canal, (also known as the sub-sartorial or the Hunter’s canal) is located within the middle third of the anterior-medial thigh and extends from the apex of the femoral triangle to the adductor hiatus. The apex of the femoral triangle is where the medial border of the sartorius muscle crosses over the medial border of the adductor longus muscle, while the adductor hiatus is an opening in the aponeurotic distal insertion of the adductor magnus muscle. In cross-section, the adductor canal is a triangular-shaped intermuscular channel bounded by the sartorius muscle (anteromedial), vastus medialis muscle (anterolateral), and both the adductor longus as well as the adductor magnus (posteromedial) muscles[13,14]. The roof of the adductor canal is formed by the subsartorial fascia, which extends across the adductor canal from the medial border of the vastus medialis to the lateral border of the adductor longus proximally and adductor magnus distally. The distal aspect of the subsartorial fascia is also known as the vastoadductor membrane[15,16].

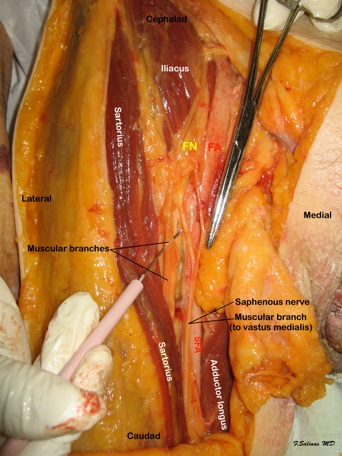

Within this triangular space, the contents of the adductor canal have traditionally been described as the femoral artery and vein, two fascicular branches of the femoral nerve; the saphenous nerve and the nerve to the vastus medialis, and the articular contribution of the obturator nerve, which enters the distal adductor canal just proximal to the adductor hiatus[17]. However, a recent detailed anatomical study indicates that while the nerve to the vastus medialis courses distally along the anteromedial border of the vastus medialis muscle in close proximity to the adductor canal and parallel to the saphenous nerve (Figure 1), it may not actually be located within the adductor canal proper[15]. Furthermore, the nerve to the vastus medialis muscle is contained within a bilayer fascial tunnel that lies between the adductor longus and vastus medialis muscles, separated from the adductor canal[18]. The saphenous nerve initially is located lateral to the femoral artery, then courses anteriorly and eventually located medial to the femoral artery in the distal aspect of the adductor canal. The saphenous nerve exits through the vastoadductor membrane where the femoral vessels course deeper into the distal thigh passing through the adductor hiatus to become the popliteal vessels. The descending path of the saphenous nerve, most consistently found within the adductor canal, has been well described by Mansour[19].

Figure 1: Dissection of the adductor canal at mid thigh level. The sartorius muscle is retracted laterally to expose the adductor canal contents. The saphenous nerve and the nerve to the vastus medialis course laterally to the superficial femoral artery (SFA). FN- Femoral nerve; FA- Femoral artery

Research Methods

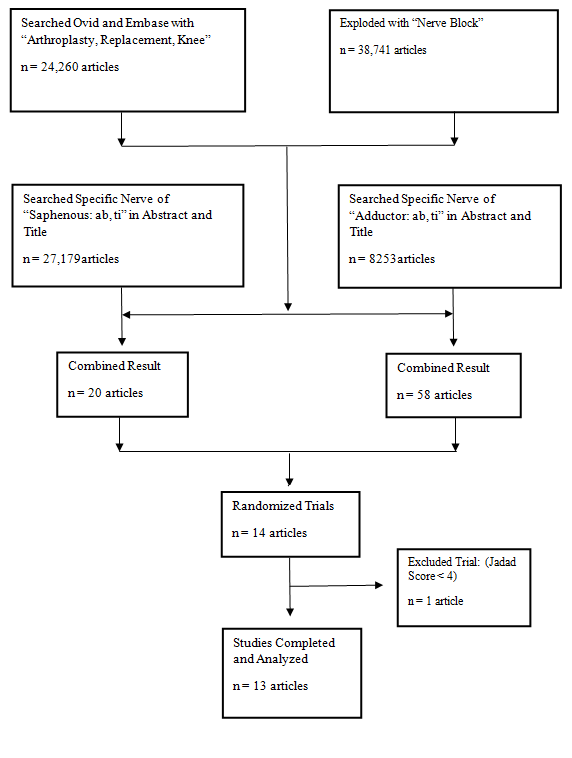

We performed a systematic review of all contemporary relevant publications on Medline and Embase (Figure 2). Population search MeSH terms included the following: “Replacement,” “Arthroplasty,” and “Nerve Block” with combined of specific nerves “saphenous,” and “adductor”. In addition, date range from 2009 to November 2015 was used to identify a total of 78 abstracts. A search prior to 2009 showed no revelant abstracts to the purpose of this article. All articles were reviewed, which included 13 randomized controlled trials Tabel with Jadad scores ≥ 4[20].

Figure 2: Flow diagram of the literature search.

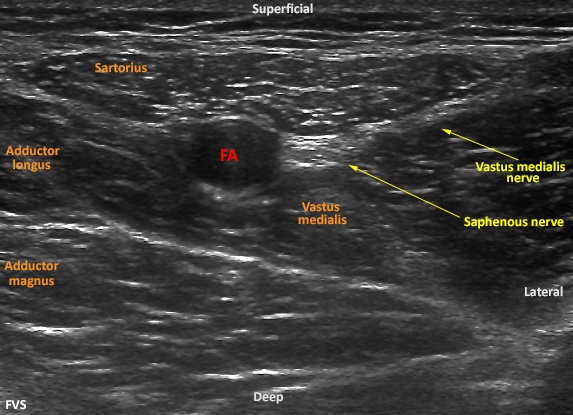

Ultrasound-guided technique for performing adductor canal block

To perform an ultrasound-guided ACB, patients are typically placed in the supine position. The operative extremity is abducted and externally rotated with the skin prepped and draped over the middle third of the anteromedial thigh. Typically, a high frequency linear array ultrasound transducer is used to identify the target location where the Superficial Femoral Artery (SFA) can be identified deep to the middle third of the sartorius muscle (Figure 3). The hyperechoic saphenous nerve is usually located anterior-lateral to the pulsatile anechoic SFA. After obtaining the appropriate short-axis view of the target anatomical structures, a block needle is then advanced in-plane immediately inferior to the saphenous nerve, and local anesthetic is incrementally injected to achieve perinenural distribution within the adductor canal. Most published studies report an initial bolus volume of 30 milliliters (mL)[21] but others have been successful with as little as 15 mL of local anesthetics[22]. A catheter may also be deployed at this location for a continuous infusion or an intermittent bolus technique[23]. To date, there is no rigorous evidence to support either the optimal minimum local anesthetic volume and concentration or perineural distribution to achieve a successful adductor canal block. Confirmation of successful adductor canal block after total knee arthroplasty should be confirmed with sensory loss along the medial lower leg (distribution of the distal sartorial sensory branch). Testing sensory loss in the infrapatellar sensory distribution may be hampered by the presence of bandages around the knee, as well as a high percentage of postoperative hypoesthesia in the infrapatellar distribution due to surgical trauma[24,25].

Figure 3: Ultrasound imaging of short-axis view of middle of the thigh. Superficial femoral artery (FA) is identified deep to the sartorius muscle. The hyperechoic saphenous nerve is located anterior-lateral to the artery. A branch of the vastus medialis nerve is shown laterlaly as it courses to the vastus medialis muscle.

Analgesic efficacy

The knee joint is primarily innervated by the femoral, the obturator, and the sciatic nerves[17,26,27]. Although, minimally invasive surgical techniques have resulted in less tissue trauma, the question remains regarding to the optimal postoperative analgesic regimen. With recent insurance reimbursement model changes[28,29], attention has shifted to focus even more on the further improvement of analgesia for patient satisfaction[30] and in efforts to decrease the length of hospitalization.

The approach to anesthetize the saphenous nerve within the adductor canal has been long entertained to provide analgesia to the medial aspect of the ankle and foot[31]. However, the concept of using this block for TKA is a fairly recent innovation. In 2011, Lund et al. were the first to image the spread of a 30 mL local anesthetic bolus within the adductor canal through magnetic resonance imaging[21]. The authors believed that the administration of local anesthetic into this canal may be an effective adjunct to postoperative analgesia for TKA. One year later, this hypothesis was tested in a proof-of-concept RCT in patients with established severe knee pain within 30 minutes after emergence from general anesthesia for TKA[12]. There was no significant reduction in dynamic (45-degree active knee flexion after ACB with 30 mL either of ropivacaine 0.75% or saline placebo) VAS pain scores. The lack of difference in immediate active VAS scores may have been influenced by the relatively large amounts of systemic opioids (200 - 225 micrograms fentanyl and 12 - 13.5 mg morphine) administered to the patients 30 minutes prior to emergence from anesthesia. However, there was a significant reduction in active VAS scores between 30 minutes and 360 minutes (secondary outcome) after ACB was measured by area under the curve[12]. To model the effect of a continuous infusion, Jenstrup et al. reported results in a subsequent RCT using a continuous ACB (initial loading dose of 30 mL ropivacaine 0.75%, followed by intermittent bolus of 15 mL of either ropivacaine 0.75% ropivacaine or saline) at time intervals of 6, 12, and 18 hour postoperatively)[32]. In this trial, both cumulative morphine consumption at 24 hours (primary outcome) and dynamic analgesia pain scores were significantly improved compared to placebo. The authors postulated that intermittent boluses, as opposed to a true continuous infusion, may have resulted in a wider spread of local anesthetic and contributed to the improved analgesic efficacy. This benefit of an intermittent bolus regimens has been demonstrated in labor analgesia[33,34] and continuous interscalene analgesia[35].

Many have previously questioned whether a continuous adductor canal infusion can provide satisfactory analgesia after TKA. Hanson et al. investigated the opioid-sparing effect of a continuous infusion of 0.2% ropivacaine versus sham catheter (placed in the sartorius muscle) with saline in TKA patients who initially received a single-injection femoral nerve block[23]. Of the 76 patients, cumulative 48-h postoperative morphine consumption, the primary outcome, was recorded. Although pain scores were different only during the first 30 hours, total morphine used was significantly reduced by 16.7 mg, with the greatest effect noted between 16 - 48hrs, presumably when the analgesic effects of the single injection femoral block had dissipated.

In a different study design, patients undergoing TKA with a standardized multimodal analgesic regimen (oral multimodal medications, a single 8-mg dose of intravenous dexamethasone, and high local infiltration analgesia with 200 mg ropivacaine) were randomized to continuous adductor catheters initially bloused with 15 ml of ropivacaine 0.75% followed by twice daily 15 mL dosing (8:00 AM and 8:00 PM) with either ropivacaine 0.75% or saline placebo through the evening of postoperative day 2[36]. The authors reported that a continuous ACB provided significantly improved resting and dynamic analgesia, but only in the evening of the day of surgery. Although this study did not show any benefit of continuous ACB beyond the day of surgery, the true analgesic benefits may have been underestimated due to scheduled acetaminophen and extended-release opioids (20 mg sustained-release morphine daily total) and high incidence of catheter dislodgement from the adductor canal.

Further studies also supports the analgesic efficacy of ACB after TKA[37,38]. In one trial, continuous adductor canal catheters with intermittent bolus dosing of ropivacaine 0.75% or saline after revision TKA reported significant reduction in dynamic pain only at 4 hours after the initial loading dose. All other postoperative VAS (resting and dynamic) scores and opioid requirements over the first 48 hours were not significantly different[38]. However, this study was likely to be influenced by type-2 errors due to a large dropout rate (thus falling short of the minimum sample size requirement), the high incidence (60% of all patients in both groups) of chronic preoperative opioids, and the heterogeneous surgical population (with more than 50% in each group presented for either 2nd or even 3rd revision TKA). However, positive results were also conveyed in two other RCTs where pain scores and opioid consumption (secondary outcomes) with ACBs were not inferior to FNBs[39,40]. Most recently, Memtsoudis and colleagues have shown there was no significant difference in VAS scores between FNB and ACB groups during rest and passive movement[41].

Early postoperative functional outcome

Inpatient falls are considered hospital-acquired events and categorized as “never events” by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services[42]. These falls cost an average of $4000 per incident and are usually not reimbursed by Medicare[43,44]. Recently, FNBs have fallen out of favor in many lower extremity surgeries due to the potential fall risk from quadriceps weakness[45,46]. The risk of fall with FNBs has been quoted as high as 7 percent[47,48], but Memtsoudis et al. argued that this association may not completely be anesthesia related. In this large analysis of 191,570 patients from a national insurance database, they reported a fall incidence of only 1.6% after TKA, and the only two independent risk factors were advanced age and high comorbidity[42]. These findings highlight that one must remain cautious in assuming that lower extremity peripheral nerve blocks are the sole cause of inpatient falls after TKA. In fact, despite a comprehensive fall prevention program, the incidence of inpatient falls in the setting of continuous FNBs was still as high 2.7%[49]. Quadriceps muscle weakness after TKA may be likely due to confounding factors such as soft tissue trauma and interstitial edem[50].

ACB has been consistently shown to preserve the majority of Quadriceps Motor Strength (QMS) and may enhance objective measures of functional mobility to facilitate earlier ambulation and attainment of functional milestones[51-53]. In two volunteer RCTs[53,54], ACBs and FNBs were directly compared using a randomized crossover sequence design. Both trials demonstrated significantly less reduction of QMS in the ACB groups. However, because the volunteer subjects did not actually undergo TKAs, the authors cautioned that a definitive correlation should not be extrapolated to TKA patients. Nevertheless, targeting healthy volunteers eliminated confounding variables such as pain response, opioid consumption, surgical dressing, and psychosocial issues related to surgery and hospitalization.

The first double-blinded RCT comparing ambulation function with either continuous ACB or continuous FNB after TKA was performed by Jaeger et al[40]. The authors demonstrated that postoperative QMS (measured as percentage of baseline Quadriceps Maximal Voluntary Isometric Contraction [Q-MVIC]) was significantly higher in the ACB than the FNB group (52% vs. 18% of baseline Q-MVIC, P = 0.004). However, this study failed to show any significant difference between the two groups in terms of mobility testing (Timed-Up-and-Go test and the 10-point mobility scale). Subsequent RCTs provided further evidence that ACBs (single-injection or continuous technique) preserved QMS and enhanced measures of functional mobility after TKA, directly as compared to placebo[23], and to FNBs[39,55,56]. Additionally, recent retrospective cohort studies also provided evidence that ACB enhanced early ambulation, while maintaining equivalent analgesic efficacy[51,52]. However, none of these studies demonstrated a reduction in hospital length of stay.

Despite the advantages of QMS preservation and early enhanced mobility with ACB, a recently published RCT demonstrated that while a continuous ACB (48hr duration) provided significantly better analgesia compared to a single-injection, there was no difference between the techniques in terms of time to attain functional milestones (time to ambulation with a walker, staircase competency, or ambulation distance and maximal flexion at discharge)[57]. Thus, the optimal delivery of ACB and its role in enhancing early recovery and discharge within established clinical TKA pathways merits further clinical investigation.

Adverse effects

The incidence of nerve injury with peripheral nerve blocks depends on the particular definition of injury. Reported frequency of permanent neuropathy ranged between 1.5/10,000 to 9/10,000[58,59], while this incidence was reported to be higher with continuous catheters[60,61]. Henningsen et al. followed 97 patients after ACB catheter and found no definitive saphenous nerve injury related to the block itself. But 84% of the patients had signs of injury to the infrapatellar branch in the anatomical distribution of the surgical incision[24], which may attributed to surgical injury.

A unique effect to the ACB is the potential cephalad spread of local anesthetic within the adductor canal, with potential blockade of the more proximal femoral motor nerve branches within the femoral triangle. Such spread patterns were previously described in two reports of single injection[62,63] and continuous infusion in vivo[64]. This phenomenon has been well described in cadaveric dye studies[15,65]. Rarely, unrecognized cephalad spread of local anesthetic can lead to substantial quadriceps weakness. Gautier et al. reported a case where continuous ACB was performed with initial bolus of local anesthetic for anterior cruciate ligament repair and resulted in dorsiflexion weakness of the foot[66]. Subsequently, contrast was injected into the catheter and computer tomography revealed there was spread into the popliteal fossa and contacted the sciatic nerve[66]. However, Yuan et al. have demonstrated that contrast injection under controlled pressure did not routinely reach the lesser trochanter, or the location of the common femoral nerve[67]. In this study, sixty percent of subjects had contrast spread within either the same sector as the catheter tip, or one sector distally. This study demonstrated that there was limited catheter infusion spread within the adductor canal in both cephalad and caudad direction. However, the potential cephalad spread of local anesthetic within the adductor canal may place the patient at risk of quadriceps muscle weakness and fall.

Anatomically, much of the space in the adductor canal is occupied by the femoral vessels. Hence, there is a potential risk for unintended vascular puncture during the placement of ACB. Recent data shown the risk of vascular puncture decreases with ultrasound guidance, but significant bleeding and serious complications can still occur due to the inability to recognize and compress the source of bleeding[68]. Any uncooperative patient may not be a candidate for this block due to the surrounding vascular structure. Finally, the adductor canal is bounded by intermuscular compartments. Although no published report currently exists, leaking of local anesthetic from the potentially fenestrated vastoadductor membrane or the migration of catheter tip outside of the adductor canal can result in possible delayed myositis or even local anesthetic systemic toxicity[14]. There has been one report of a patient developing a hematoma around the adductor canal injection site after catheter removal, who subsequently developed saphenous distribution neuropathy that required 4 months of gabapentin treatment before resolution of symptoms[36].

Future directions

The search for the optimal postoperative analgesic regimen for TKA continues. Perhaps one day we may discover a highly selective local anesthetic which targets only the sensory fibers while completely sparing motor function[69]. In a way, the ACB may already provide this goal by primarily blocking the predominant afferent sensation from the knee without significant effect on QMS[70]. For further improvement of clinical outcomes, we must focus our attention on the optimal anatomical approach and technique for adductor canal catheter placement, as well as the optimal delivery and duration of continuous infusions in order reduce to the potential block-related complications and retain the demonstrated analgesic benefits. As of yet, only a few studies have compared various approaches of the ACB, but none with clinically meaningful primary outcomes[71,72]. Additionally, while both continuous infusion and intermittent bolus techniques have been demonstrated to provide analgesic efficacy, there is a lack of evidence of which is the ideal method. Furthermore, the optimal volumes and concentrations for either continuous or intermittent bolus techniques require further investigation in quality RCTs.

Conclusion

The positive impact of regional anesthesia on surgical outcome has continued to evolve, most recently with the introduction of the ACB for TKA. It has enhanced patient recovery by not only providing analgesia that is non inferior compared to FNB, but has done so while preserving, and in some instances, actually improving QMS due to blunting of the well-known pain-mediated quadriceps dysfunction from TKA. In summary, the evidence supports that in the setting of varied comprehensive preoperative multimodal analgesic regimens (LIA, oral NSAIDs, acetaminophen, gabapentinoids, and opioid analgesic), ACB has been consistently demonstrated to provide non inferior analgesic efficacy compared to FNB. Furthermore, ACB minimizes the efferent motor weakness associated with FNB. Based on current evidence to date, we conclude that ACB could replace FNB, as the first option for peripheral regional anesthetic technique after TKA.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Table 1:

| Author Year | Methodology | Primary Outcome | Significant Secondary Outcomes | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jenstrup et al.[32] 2012 | 71 patients. ACB placed in PACU. 30 mL loading dose followed by intermittent boluses via AC catheters with either 15 mL R 0.75% or NS every 6hr. at 6, 12, 18 and 24 hr. |

Morphine consumption significantly decreased with R vs. NS (40 ± 21 vs. 56 ± 21 mg) for 1st 24 hr., P = 0.006. | Active VAS scores lower with R (P = 0.01), but not at rest (P = 0.06). Ropivacaine group performed ambulation and TUG tests at 24 hr. better. No difference in PONV. | First RCT to demonstrate analgesic efficacy of ACB. VAS scores decreased and TUG improved significantly in NS group after receiving R bolus @ 24 h. |

| Jæger et al.[12] 2012 | 41 patients. ACB placed in PACU. Injected 30 ml of R 0.75% or NS. |

Active VAS score (45o active knee flexion) were not improved with R = 58 (22) mm vs. NS 67 (29) mm, P = 0.23. | Significant difference of VAS scores (AUC) between R vs. NS from 1 to 6 hr. (P = 0.02). No difference in resting VAS pain and morphine consumption. |

Results may have been blunted due to large amount of IV fentanyl (200 - 225 mg) and MSO4 (12 - 13.5 mg) given in both groups. Post-hoc analysis revealed significant reduction in VAS score at 2 hr. post -block. |

| Andersen et al.[36] 2013 | 40 patients. High volume intraoperative local infiltration analgesia (R 0.2%). AC catheters were placed postoperatively with 15-mL boluses of either R 7.5% or NS twice daily for 2 days. |

Worst pain scores significantly reduced in R group during movement (3 vs. 5.5, P < 0.050) and at rest (2 vs. 4, P = 0.032) on the day of surgery. | Ropivacaine also improved sleep and ambulation. No difference in VAS scores beyond POD0, morphine consumption, PONV, or LOS. | No analgesic benefit (vs. placebo) beyond POD1. High incidence of catheter dislodgement by POD2 (may be related to leg movements). One patient had 4-month duration of saphenous neuropathy. |

| Jæger et al.[54] 2013 | 11 volunteers studied on 2 separate days. (Crossover study). Day 1: ACB in one leg and FNB in opposite leg: R 0.1% (30 mL) or NS (30 mL). Day 2: reversed order from day 1. |

Mean Q-MVIC was significantly reduced (by 8%) with ACB R vs. placebo (5.0 ± 1.0 vs. 5.9 ± 0.6, P = 0.02) | Q-MVIC was also reduced with FNB vs. placebo (P = 0.0004), and FNB vs. ACB (P = 0.002). No difference in adductor strength MVIC between ACB vs. FNB, and ACB vs. placebo. |

Most important finding was that ACB only decreased Q-MVIC by 8% vs. FNB by 49% compared to baseline. Performance in mobilization tests (TUG test, 10m walk, 30s chair stand) reduced after FNB compared with ACB. |

| Kwofie et al.[53] 2013 | 16 patients. ACB performed in one leg and FNB in opposite leg. 15 mL of 3% 2-chloroprocaine or NS was injected. |

Q-MVICs were 95.1 ± 17.1% baseline in ACB group and 11.1 ± 14.0% baseline in FNB group (P < 0.0001) 30 minutes after block placement | Berge balance scores were significantly impaired after FNB vs. no impairment after ACB. | ACB does not result in a clinically relevant decrease in Q-MVIC. Volunteer study, therefore cannot assess results in patients undergoing TKAs. |

| Jæger et al.[40] 2013 | 48 patients received both AC and FN catheters (one catheter with 30 mL bolus R 0.75%, followed by continuous R 0.2% @ 8 mL/h vs. sham infusion in other catheter) for 24 hr. | Q-MVIC at 24hr was significantly higher with continuous ACB 52% (9% - 92%) vs. FNB 18% (0 - 69%), P = 0.004. | No difference in postoperative resting or dynamic VAS scores, morphine consumption, or mobility testing. | Continuous ACB preserved quadriceps motor strength better than continuous FNB after TKA, while providing non-inferior analgesic efficacy. Lack of improvement in mobility may have been influenced by use of full wheel walker in all patients. |

| Kim et al.[39] 2014 | 93 patients. TKAs under combine spinal-epidural. ACB: low adductor canal approach with 15 mL bupivacaine 0.5%. FNB: 30 mL bupivacaine 0.25%. Q-MVIC assessed @ baseline, 6 to 8, 24, 48 hr. after surgery. |

At 6 to 8 hr. after surgery, ACB group had significantly higher median quadriceps strength versus FNB (6.1 kgf vs. 0 kgf, P < 0.0001) ACB was not inferior to FNB in terms of either VAS scores or opioid consumption. | At 24 and 48 hr., there was no difference in quadriceps strength, pain scores, or opioid consumption between ACB and FNB groups. | Confounding factor may have been the use of CLEA through evening of POD1. However, CLEA was used in both groups and quadriceps strength was preserved equally in the non-operative leg. |

| Hanson et al.[23] 2014 | 76 patients. Received either AC catheters with 0.2% ropivacaine or sham infusion (in Sartorius muscle with NS). All patients received a preoperative single-injection FNB (20 mL R 0.5%) |

48-hr cumulative IV morphine consumption significantly decreased with continuous ACB (46.7 mg) vs. no ACB (63.4 mg), P = 0.013. | Continuous ACB improved quadriceps strength (P = 0.010) and ambulation (P = 0.034) on beginning on POD2. | Morphine consumption decreased (26%) with continuous ACB and notably separated starting at 16 - 48 hr. with resolution of single injection FNB. Quadriceps strength increased from 55% to 77% of preoperative baseline from POD1 to POD2 with continuous ACB vs. no improvement without continuous ACB. |

| Grevstad et al.[37] 2014 | 50 patients with established severe dynamic pain after TKA on POD1 or POD2. Group A: AC injection with 30 ml of R 0.75% after obtaining pre-block VAS score (T-0) followed by 30 mL NS AC injection 45 minutes later (T-45). Group B: AC injection with NS at T-0 and 30 mL of R0.75% at T-45. |

Dynamic VAS pain score significantly decreased (32 mm difference) with ACB vs. no ACB (P < 0.0001) at T45. | Resting VAS pain score also significantly improved (15 mm difference) with ACB vs. no ACB at T-45. No difference in VAS scores 45 minutes after second injection (T-90). |

Only included patients with established severe dynamic knee pain despite a comprehensive postoperative multimodal analgesic regimen. Established analgesic efficacy of a “rescue” ACB by initial difference at after 1st block, followed by equivalent analgesia between groups at T90 after Group B received an ACB. |

| Shah et al.[56] 2014 | 100 patients. Continuous AC catheters vs. continuous FN catheters. 30 mL initial bolus dose R 0.75%, followed by intermittent repeat boluses of 30 mL R 0.25% every 4 hr. through morning of POD2. |

Ambulation ability significantly better with CACB vs. CFNB (TUG test: 51 (7.9) vs. 180 (67); 10-m walk test: 67s (7.3) vs. 274s (103); and 30-sec chair test: 5.25 repetitions (0.7) vs. 1.5 repetitions (0.8). | Functional milestones also (straight leg raise, quad-stick ambulation, staircase competency, and ambulation distance) all improved with CACB. No difference in maximal knee flexion, VAS scores, or rescue analgesic requirements with tramadol. |

No significant difference in pain control between the two groups. ACB was neither superior nor inferior to FNB in terms of analgesic efficacy. Trend to decrease in hospital LOS of 3.08 vs. 3.92 (P < 0.001) with CACB vs. CFNB (study not powered LOS outcome). |

| Jæger et al.[38] 2014 | 30 patients. AC catheter with either 30 mL of R 0.75% or NS bolus followed by an infusion of R 0.2% or NS beginning 6 hrs after bolus. |

Significant difference dynamic pain scores with knee flexion; 52 (22) mm with R and 71 (25) mm with NS (P = 0.04) only at 4hr after initial block. | No significant difference in either resting or dynamic area under the curve analgesia through 1st 24 hr. | Underpowered study due to a large dropout rate. Heterogeneous population with about 50% in each group presenting for 2nd or 3rd TKA revision; and 60% in each group on chronic preoperative opioid therapy. |

| Memtsoudis et al.[41] 2015 | 60 patients. Combined spinal epidural anesthesia for bilateral TKAs. Single-injection of FNB (30 ml bupivacaine 0.25%) and single-injection ACB (15 ml bupivacaine 0.25%), side to side, in the same patient. |

No significant differences in VAS scores between FNB and ACB group at rest or continuous passive movement (P = 0.4154). | No differences between the extremity with ACB vs. the extremity with FNB in decline in postoperative quadriceps motor strength or physical therapy milestones. | Question contribution of epidural analgesia to bilateral quadriceps weakness, as well as the effects of pain, swelling, and physiological impact of bilateral TKAs vs. unilateral TKA. |

| Grevstad et al.[55] 2015 | 50 patients with established severe dynamic pain after TKA on POD1 or POD2. Group ACB: Single-injection ACB with 30 mL R 0.2% and single injection FNB with 30 mL NS. Group FNB: single-injection of ACB with 30 mL NS and single –injection FNB with 30 mL of R 0.2%. |

Two hr. after blocks performed, Q-MVIC increased to 193% from baseline in the ACB group vs. a decline to 16% of baseline values for the FNB group (P < 0.0001). | No significant difference in either resting, dynamic, or “worst” VAS between ACB vs. FNB. 7 of 25 in the FNB group vs. 0 of 25 in the ACB group were unable to perform TUG test post-block. ACB group performed TUG test significantly faster (mean difference 20 seconds) vs. FNB group. |

Only included patients with established severe dynamic knee pain. 1st clinical study to demonstrate that ACB can actually increase quadriceps strength (almost doubled from baseline pre-block strength). Further confirmation that ACB and FNB seem to have similar analgesic efficacy. |

| Shah et al.[57] 2015 | 97 patients. Single-injection ACB vs Continuous ACB: Initial 30 mL loading dose of R 0.75% via catheter followed by intermittent 30 mL NS every 4 hr. through morning POD2. |

Postoperative resting and dynamic pain scores decreased in CACB (mean difference 4-7/100 mm difference at rest and 7-10/100 with activity) through POD2. | No significant difference in ambulation ability (TUG test, 10-m walk test, 30-s chair test), achievement of functional milestones, or hospital LOS. | All patients received single injection LIA with 20 mL 0.25% bupivacaine + 40 mg triamcinolone acetate. |

References

- 1. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.

- 2. Kurtz, S., Ong, K., Lau, E., et al. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. (2007) J Bone Joint Surg Am 89(4): 780-785.

- 3. Cram, P., Lu, X., Kates, S.L., et al. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991-2010. (2012) JAMA 308(12): 1227-1236.

- 4. Ibrahim, M.S., Khan, M.A., Nizam, I., et al. Peri-operative interventions producing better functional outcomes and enhanced recovery following total hip and knee arthroplasty: an evidence-based review. (2013) BMC Med 11: 37.

- 5. Kehlet, H., Thienpont, E. Fast-track knee arthroplasty - status and future challenges. (2013) Knee 20 (S1,S29): 33.

- 6. Clarke, H.A., Katz, J., McCartney, C.J., et al. Perioperative gabapentin reduces 24 h opioid consumption and improves in-hospital rehabilitation but not post-discharge outcomes after total knee arthroplasty with peripheral nerve block. (2014) Br J Anaesth 113(5): 855-864.

- 7. Huang, Y.M., Wang, C.M., Wang, C.T., et al. Perioperative celecoxib administration for pain management after total knee arthroplasty - a randomized, controlled study. (2008) BMC Musculoskelet Disord 9: 77.

- 8. Backes, J.R., Bentley, J.C., Politi, J.R., et al. Dexamethasone reduces length of hospitalization and improves postoperative pain and nausea after total joint arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. (2013) J Arthroplasty 28(Suppl 8): 11-17.

- 9. Andersen, L.O., Kehlet, H. Analgesic efficacy of local infiltration analgesia in hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. (2014) Br J Anaesth 113(3): 360-374.

- 10. Choi, P.T., Bhandari, M., Scott, J., et al. Epidural analgesia for pain relief following hip or knee replacement. (2003) The Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD003071.

- 11. Hadzic, A., Houle, T.T., Capdevila, X., et al. Femoral nerve block for analgesia in patients having knee arthroplasty. (2010) Anesthesiology 113(5): 1014-1015.

- 12. Jaeger, P., Grevstad, U., Henningsen, M.H., et al. Effect of adductor-canal-blockade on established, severe post-operative pain after total knee arthroplasty: a randomised study. (2012) Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 56(8): 1013-1019.

- 13. Tank, P.W. Grant's Dissector. (2005)13 edition Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- 14. Tubbs, R.S., Loukas, M., Shoja, M.M., et al. Anatomy and potential clinical significance of the vastoadductor membrane. (2007) Surg Radiol Anat 29(7): 569-573.

- 15. Andersen, H.L., Andersen, S.L., Tranum-Jensen, J. The spread of injectate during saphenous nerve block at the adductor canal: a cadaver study. (2015) Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 59(2): 238-245.

- 16. Cowlishaw, P., Kotze, P. Adductor canal block-or subsartorial canal block? (2015) Reg Anesth Pain Med 40(2): 175-176.

- 17. Gardner, E. The innervation of the knee joint. (1948) Anat Rec 101(1): 109-130.

- 18. Ozer, H., Tekdemir, I., Elhan, A., et al. A clinical case and anatomical study of the innervation supply of the vastus medialis muscle. (2004) Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 12(2): 119-122.

- 19. Mansour, N.Y. Sub-sartorial saphenous nerve block with the aid of nerve stimulator. (1993) Reg Anesth 18(4): 266-268.

- 20. Olivo, S.A., Macedo, L.G., Gadotti, I.C. Scales to assess the quality of randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. (2008) Phys Ther 88(2): 156-175.

- 21. Lund, J., Jenstrup, M.T., Jaeger, P., et al. Continuous adductor-canal-blockade for adjuvant post-operative analgesia after major knee surgery: preliminary results. (2011) Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 55(1): 14-19.

- 22. Hanson, N.A., Derby, R.E., Auyong, D.B., et al. Ultrasound-guided adductor canal block for arthroscopic medial meniscectomy: a randomized, double-blind trial. (2013) Can J Anaesth 60(9): 874-880.

- 23. Hanson, N.A., Allen, C.J., Hostetter, L.S., et al. Continuous ultrasound-guided adductor canal block for total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind trial. (2014) Anesth Analg 118(6): 1370-1377.

- 24. Henningsen, M.H., Jaeger, P., Hilsted, K.L., et al. Prevalence of saphenous nerve injury after adductor-canal-blockade in patients receiving total knee arthroplasty. (2013) Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 57(1): 112-117.

- 25. Laffosse, J.M., Potapov, A., Malo, M., et al. Hypesthesia after anterolateral versus midline skin incision in TKA: a randomized study. (2011) Clin Orthop Relat Res 469(11): 3154-3163.

- 26. Kennedy, J.C., Alexander, I.J., Hayes, K.C. Nerve supply of the human knee and its functional importance. (1982) The American journal of sports medicine 10(6): 329-335.

- 27. Horner, G., Dellon, A.L. Innervation of the human knee joint and implications for surgery. (1994) Clin Orthop Relat Res 301: 221-226.

- 28. Froimson, M.I., Rana, A., White, R.E., et al. Bundled payments for care improvement initiative: the next evolution of payment formulations: AAHKS Bundled Payment Task Force. (2013) J Arthroplasty 28(8 suppl): 157-165.

- 29. Rana, A.J., Bozic, K.J. Bundled payments in orthopaedics. (2015) Clin Orthop Relat Res 473(2): 422-425.

- 30. Gupta, A., Lee, L.K., Mojica, J.J., et al. Patient perception of pain care in the United States: a 5-year comparative analysis of hospital consumer assessment of health care providers and systems. (2014) Pain Physician 17(5): 369-377.

- 31. Manickam, B., Perlas, A., Duggan, E., et al. Feasibility and efficacy of ultrasound-guided block of the saphenous nerve in the adductor canal. (2009) Reg Anesth Pain Med 34(6): 578-580.

- 32. Jenstrup, M.T., Jæger, P., Lund, J., et al. Effects of adductor-canal-blockade on pain and ambulation after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized study. (2012) Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 56(3): 357-364.

- 33. George, R.B., Allen, T.K., Habib, A.S. Intermittent epidural bolus compared with continuous epidural infusions for labor analgesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. (2013) Anesth Analg 116(1): 133-144.

- 34. Kaynar, A.M., Shankar, K.B. Epidural infusion: continuous or bolus? (1999) Anesth Analg 89(2): 534.

- 35. Fredrickson, M.J., Abeysekera, A., Price, D.J., et al. Patient-initiated mandatory boluses for ambulatory continuous interscalene analgesia: an effective strategy for optimizing analgesia and minimizing side-effects. (2011) Br J Anaesth 106(2): 239-245.

- 36. Andersen, H.L., Gyrn, J., Moller, L., et al. Continuous saphenous nerve block as supplement to single-dose local infiltration analgesia for postoperative pain management after total knee arthroplasty. (2013) Reg Anesth Pain Med 38(2): 106-111.

- 37. Grevstad, U., Mathiesen, O., Lind, T., et al. Effect of adductor canal block on pain in patients with severe pain after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized study with individual patient analysis. (2014) Br J Anaesth 112(5): 912-919.

- 38. Jaeger, P., Koscielniak-Nielsen, Z.J., Schrøder, H.M., et al. Adductor canal block for postoperative pain treatment after revision knee arthroplasty: a blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled study. (2014) PloS One 9(11): e11195.

- 39. Kim, D.H., Lin, Y., Goytizolo, E.A., et al. Adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block for total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. (2014) Anesthesiology 120(3): 540-550.

- 40. Jaeger, P., Zaric, D., Fomsgaard, J.S., et al. Adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block for analgesia after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind study. (2013) Reg Anesth Pain Med 38(6): 526-532.

- 41. Memtsoudis, S.G., Yoo, D., Stundner, O., et al. Subsartorial adductor canal vs femoral nerve block for analgesia after total knee replacement. (2015) Int Orthop 39(4): 673-680.

- 42. Memtsoudis, S.G., Danninger, T., Rasul, R., et al. Inpatient falls after total knee arthroplasty: the role of anesthesia type and peripheral nerve blocks. (2014) Anesthesiology 120(3): 551-563.

- 43. Cui, Q., Schapiro, L.H., Kinney, M.C., et al. Reducing costly falls of total knee replacement patients. (2013) Am J Med Qual 28(4): 335-338.

- 44. Inouye, S.K., Brown, C.J., Tinetti, M.E. Medicare nonpayment, hospital falls, and unintended consequences. (2009) N Engl J Med 360(23): 2390-2393.

- 45. Feibel, R.J., Dervin, G.F., Kim, P.R., et al. Major complications associated with femoral nerve catheters for knee arthroplasty: a word of caution. (2009) J Arthroplasty 24(6 Suppl): 132-137.

- 46. Sharma, S., Iorio, R., Specht, L.M., et al. Complications of femoral nerve block for total knee arthroplasty. (2010) Clin Orthop Relat Res 468(1): 135-140.

- 47. Ilfeld, B.M., Duke, K.B., Donohue, M.C. The association between lower extremity continuous peripheral nerve blocks and patient falls after knee and hip arthroplasty. (2010) Anesth Analg 111(6): 1552-1554.

- 48. Atkinson, H.D., Hamid, I., Gupte, C.M., et al. Postoperative fall after the use of the 3-in-1 femoral nerve block for knee surgery: a report of four cases. (2008) J Orthop Surg 16(3): 381-384.

- 49. Pelt, C.E., Anderson, A.W., Anderson, M.B., et al. Postoperative falls after total knee arthroplasty in patients with a femoral nerve catheter: can we reduce the incidence? (2014) J Arthroplasty 29(6): 1154-1157.

- 50. Holm, B., Kristensen, M.T., Bencke, J., et al. Loss of knee-extension strength is related to knee swelling after total knee arthroplasty. (2010) Arch Phys Med Rehabil 91(11): 1770-1776.

- 51. Mudumbai, S.C, Kim, T.E., Howard, S.K., et al. Continuous adductor canal blocks are superior to continuous femoral nerve blocks in promoting early ambulation after TKA. (2014) Clin Orthop Relat Res 472(5): 1377-1382.

- 52. Perlas, A., Kirkham, K.R., Billing, R., et al. The impact of analgesic modality on early ambulation following total knee arthroplasty. (2013) Reg Anesth Pain Med 38(4): 334-339.

- 53. Kwofie, M.K., Shastri, U.D., Gadsden, J.C., et al. The effects of ultrasound-guided adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block on quadriceps strength and fall risk: a blinded, randomized trial of volunteers. (2013) Reg Anesth Pain Med 38(4): 321-325.

- 54. Jaeger, P., Nielsen, Z.J., Henningsen, M.H., et al. Adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block and quadriceps strength: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy volunteers. (2013) Anesthesiology 118(12): 409-415.

- 55. Grevstad, U., Mathiesen, O., Valentiner, L.S., et al. Effect of adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block on quadriceps strength, mobilization, and pain after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, blinded study. (2015) Reg Anesth Pain Med 40(1): 3-10.

- 56. Shah, N.A., Jain, N.P. Is continuous adductor canal block better than continuous femoral nerve block after total knee arthroplasty? Effect on ambulation ability, early functional recovery and pain control: a randomized controlled trial. (2014) J Arthroplasty 29(11): 2224-2229.

- 57. Shah, N.A, Jain, N.P., Panchal, K.A. Adductor Canal Blockade Following Total Knee Arthroplasty-Continuous or Single Shot Technique? Role in Postoperative Analgesia, Ambulation Ability and Early Functional Recovery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. (2015) J Arthroplasty 30(8): 1476-1481.

- 58. Auroy, Y., Benhamou, D., Bargues, L., et al. Major complications of regional anesthesia in France: The SOS Regional Anesthesia Hotline Service. (2002) Anesthesiology 97(5): 1274-1280.

- 59. Sites, B.D., Taenzer, A.H., Herrick, M.D., et al. Incidence of local anesthetic systemic toxicity and postoperative neurologic symptoms associated with 12,668 ultrasound-guided nerve blocks: an analysis from a prospective clinical registry. (2012) Reg Anesth Pain Med 37(5): 478-482.

- 60. Capdevila, X., Pirat, P., Bringuier, S., et al. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in hospital wards after orthopedic surgery: a multicenter prospective analysis of the quality of postoperative analgesia and complications in 1,416 patients. (2005) Anesthesiology 103(5): 1035-1045.

- 61. Borgeat, A., Blumenthal, S., Lambert, M., et al. The feasibility and complications of the continuous popliteal nerve block: a 1001-case survey. (2006) Anesth Analg 103(1): 229-233.

- 62. Chen, J., Lesser, J.B., Hadzic, A., et al. Adductor canal block can result in motor block of the quadriceps muscle. (2014) Reg Anesth Pain Med 39(2): 170-171.

- 63. Zhang, W., Hu, Y., Tao, Y., et al. Ultrasound-guided continuous adductor canal block for analgesia after total knee replacement. (2014) Chin Med J 127(23): 4077-4081.

- 64. Veal, C., Auyong, D.B., Hanson, N.A., et al. Delayed quadriceps weakness after continuous adductor canal block for total knee arthroplasty: a case report. (2014) Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 58(3): 362-364.

- 65. Davis, J.J., Bond, T.S., Swenson, J.D. Adductor canal block: more than just the saphenous nerve? (2009) Reg Anesth Pain Med 34(6): 618-619.

- 66. Gautier, P.E., Lecoq, J.P., Vandepitte, C., et al. Impairment of sciatic nerve function during adductor canal block. (2015) Reg Anesth Pain Med 40(1): 85-89.

- 67. Yuan, S.C., Hanson, N.A., Auyong, D.B., et al. Fluoroscopic evaluation of contrast distribution within the adductor canal. (2015) Reg Anesth Pain Med 40(2): 154-157.

- 68. Abrahams, M.S., Aziz, M.F., Fu, R.F., et al. Ultrasound guidance compared with electrcial neurostimulation for peripehral nerve blocks: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. (2009) Br J Anaesth 102(3): 408-417.

- 69. Ilfeld, B.M., Yaksh, T.L. The end of postoperative pain--a fast-approaching possibility? And, if so, will we be ready? (2009) Reg Anesth Pain Med 34(2): 85-87.

- 70. Mariano, E.R., Perlas, A. Adductor canal block for total knee arthroplasty: the perfect recipe or just one ingredient? (2014) Anesthesiology 120(3): 530-532.

- 71. Adoni, A., Paraskeuopoulos, T., Saranteas, T., et al. Prospective randomized comparison between ultrasound-guided saphenous nerve block within and distal to the adductor canal with low volume of local anesthetic. (2014) J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 30(3): 378-382.

- 72. Head, S.J., Leung, R.C., Hackman, G.P., et al. Ultrasound-guided saphenous nerve block-within versus distal to the adductor canal: a proof-of-principle randomized trial. (2015) Can J Anaesth 62(1): 37-44.