Assessment of the Physicochemical and Thermal Characterization of Biofield Energy Treated Polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA)

Alice Branton1, Mahendra Kumar Trivedi1, Dahryn Trivedi1, Gopal Nayak1, Snehasis Jana2*

Affiliation

1 Trivedi Global, Inc., Henderson, USA

2Trivedi Science Research Laboratory Pvt. Ltd., Bhopal, India

Corresponding Author

Snehasis Jana, Trivedi Science Research Laboratory Pvt. Ltd., Bhopal, India, Tel: +91-022-25811234; E-mail: publication@trivedieffect.com

Citation

Alice Branton., et al. Physicochemical and Thermal Characterization of Biofield Energy Treated Polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA). (2019) J Anal Bioanal Sep Tech 4(1): 1- 6.

Copy rights

© 2018 Alice Branton. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Polylactic-co-glycolic acid; The Trivedi Effect®; Consciousness energy healing treatment; Complementary and Alternative Medicine; PXRD; PSA; DSC; TGA/DTG

Abstract

Polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) is a biodegradable copolymer. It has many applications in the pharmaceuticals and biomedical industries, but its degradation and stability is a major concern. The objective of this study was to evaluate the influence of the Trivedi Effect® on the physicochemical and thermal properties of PLGA using modern analytical techniques. The PLGA sample was divided into control and Biofield Energy Treated parts. The control sample did not obtain the Biofield Energy Treatment, whereas the treated PLGA was received the Trivedi Effect®-Consciousness Energy Healing Treatment remotely by a renowned Biofield Energy Healer, Alice Branton. The particle size values of the treated PLGA were increased by 8.97%(d10), 8.79%(d50), 4.72%(d90), and 6.61%{D(4,3)}; thus, the surface area of treated PLGA was significantly decreased by 6.84% compared with the control sample. The latent heat of evaporation and fusion of the treated PLGA were significantly increased by 29.60% and 230.93%, respectively compared with the control sample. The residue amount was significantly increased by 21.99% in the treated PLGA compared to the control sample. The maximum thermal degradation temperature of the treated PLGA was increased by 2.30% compared with the control sample. It was concluded that the Trivedi Effect®-Consciousness Energy Healing Treatment might have generated a new form of PLGA which may show better powder flow ability, thermal stability, and minimize the hydrolysis of the ester linkages of PLGA. This improved quality of PLGA would be a better choice for the pharmaceutical formulations (i.e., the drug like simvastatin, amoxicillin, and minocycline loaded PLGA nanoparticles) and manufacturing of biomedical devices, i.e., grafts, sutures, implants, surgical sealant films, prosthetic devices, etc., in the industry using it as a raw material.

Introduction

Polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) is a synthetic copolymer of two different monomers, lactic acid, and glycolic acid. It has a great deal of attention in research and development as an alternative biodegradable polymer which has constant biodegradation rate, mechanical resistance, and regular individual chain geometry[1]. PLGA on hydrolysis of its ester linkages in the presence of water releases the monomers. These two monomers under normal physiological conditions are the by-products of various metabolic pathways in the body, hence minimum systemic toxicity. Higher the content of glycolide units in the PLGA, lower the time required for degradation. PLGA is a choice in the manufacturing of biomedical devices, i.e., grafts, sutures, implants, surgical sealant films, prosthetic devices, micro and nanoparticles[2]. Specifically, PLGA is more useful for the designing of better pharmaceuticals formulations, i.e., the drug like simvastatin, amoxicillin, vancomycin, and minocycline loaded PLGA nanoparticles could be effective in sustaining drug release for a prolonged period[3-5]. The PLGA containing less than 50% glycolic acid units is soluble in most common organic solvents, such as chloroform, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, dioxane, acetone, and tetrahydrofuran. However, PLGA rich in glycolyl units 50% and higher is insoluble in most organic solvents[6,7]. In the absence of moisture, it has adequate heat stability[8]. The degradation and stability of PLGA is a major concern, which completely depends upon the monomer distribution pattern, chain-ends chemical composition, porosity, size, shape, and presence of additives (i.e., acidic/ basic compounds, plasticizers, or drugs), moisture, and temperature[9-11].

Many Scientific study on the Trivedi Effect® (Biofield Energy Healing Treatment) has been claimed to have the significant influence on the physicochemical, thermal, and behavioural properties (crystallite size, particle size, surface area, solubility, melting point, latent heat, etc.) of various object(s)[12-14]. The Trivedi Effect® is a natural and only scientifically proven phenomenon in which a person can harness this inherently intelligent energy from the Universe and transmit it anywhere on the planet through the possible mediation of neutrinos[15]. There is a unique para-dimensional electromagnetic field generated from the continuous movement of the electrically charged particles (i.e., ions, cells, etc.) inside the body. This electromagnetic field (A Putative Energy Field) exists around the body of every living organism known as the “Biofield”. The Biofield Energy Healers have the ability to harness the energy from the Universe and can transmit into any living or non-living object(s) around the earth. All over the world the Biofield based Energy Healing Therapies have been accepted and reported in many scientific journals with significant outcomes against various disease conditions[16,17]. The Biofield Energy Healing therapy has been recognized as a Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) health care approach by the National Center of Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) with other therapies, medicines and practices such as yoga, Tai Chi, Qi Gong, homeopathy, chiropractic/osteopathic manipulation, meditation, acupressure, acupuncture, healing touch, hypnotherapy, movement therapy, naturopathy, Ayurvedic medicine, cranial sacral therapy, traditional Chinese herbs and medicines, aromatherapy, Reiki, etc., that has been accepted by the most of the U.S. population[18,19]. The Trivedi Effect®-Consciousness Energy Healing Treatment (Biofield Energy Healing Treatment) also reported with their significant outcomes in different field of sciences i.e., material science[20,21], organic chemistry[22,23], nutraceutical/pharmaceutical sciences[24,25], biotechnology[26,27], microbiology[28,29], agriculture[30,31], and medical science[32,33]. Therefore, the study was designed to evaluate the influence of the Trivedi Effect®-Consciousness Energy Healing Treatment on PLGA using powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), particle size analysis (PSA), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analytical techniques, and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)/Differential thermogravimetric analysis (DTG).

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

The polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA, 70:30) powder was purchased from Changchun Hang Gai Biological Technology Co., Ltd., China. All other chemicals used during the experiments were of analytical grade available in India.

Consciousness Energy Healing Treatment Strategies

The test sample PLGA powder was divided into two parts. One part of the test sample was treated with the Trivedi Effect®-Consciousness Energy Healing Treatment remotely under standard laboratory conditions for 3 minutes and known as a Biofield Energy Treated PLGA sample. The Biofield Energy Treatment was provided through the healer’s unique energy transmission process by the renowned Biofield Energy Healer, Alice Branton, USA, to one part of the test PLGA sample. Subsequently, the other part of the test sample was considered as a control/untreated sample (Biofield Energy Treatment was not provided). Further, the control sample was treated with a “sham” healer for the comparison with the analytical results of the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA sample. The “sham” healer did not have any knowledge about the Biofield Energy Treatment. After all, the Biofield Energy Treated and untreated PLGA samples were kept in the sealed conditions and characterized using PXRD, PSA, DSC, and TGA analytical techniques.

Characterization

The PSA, PXRD, DSC, and TGA analysis of PLGA were performed. The PXRD analysis of PLGA powder sample was performed with the help of Rigaku MiniFlex-II Desktop X-ray diffractometer (Japan)[34,35]. The average size of crystallites was calculated from PXRD data using the Scherrer’s formula (1)

G = kλ/βcosθ (1)

Where G is the crystallite size in nm, k is the equipment constant (0.94), λ is the radiation wavelength (0.154056 nm for Kα1 emission), β is the full-width at half maximum, and θ is the Bragg angle[36].

The PSA was performed using Malvern Mastersizer 2000, from the UK with a detection range between 0.01 μm to 3000 μm using the wet method. Similarly, the DSC analysis of PLGA was performed with the help of DSC Q200, TA instruments. The TGA/DTG thermograms of PLGA were obtained with the help of TGA Q50 TA instruments[37,38].

The % change in particle size, specific surface area (SSA), peak intensity, crystallite size, melting point, latent heat, weight loss and the maximum thermal degradation temperature (Tmax) of the Biofield Energy Treated sample was calculated compared with the control sample using the following equation 2:

(2)

(2)

Results and Discussion

Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) Analysis

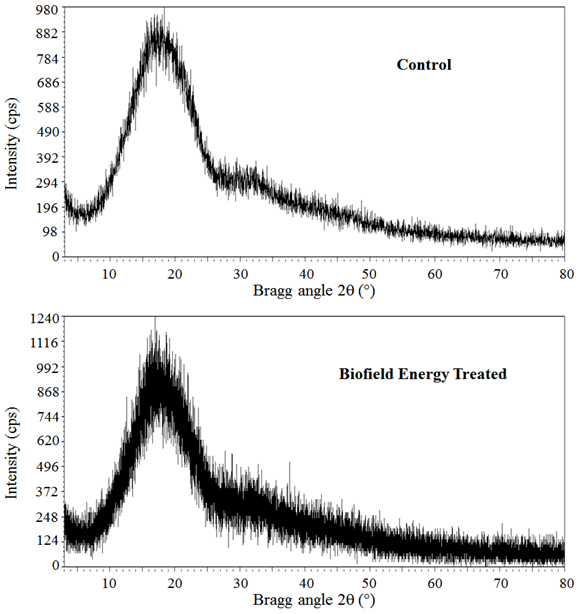

PXRD study of the control and Biofield Energy Treated PLGA was performed to determine the crystalline pattern of the samples. The PXRD experimental results of the control and Biofield Energy Treated PLGA samples did not show sharp and intense peaks in the respective diffractograms (Figure 1). Thus, it was concluded that both samples were amorphous in nature and the Biofield Energy Treatment might not affect the crystallinity and pattern of the PLGA.

Figure 1: PXRD diffractograms of the control and Biofield EnergyTreated polylactic-co-glycolic acid

Particle Size Analysis (PSA)

The PSA analysis of both the control and Biofield Energy Treated PLGA were performed, and the calculated results are presented in Table 1. The particle size values of the control sample at d10, d50, d90, and D(4,3) were 123.36 μm, 393.83 μm, 864.9 μm, and 451.581 μm, respectively. Similarly, the particle sizes of the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA at d10, d50, d90, and D(4,3) were 134.42 μm, 428.42 μm, 905.69 μm, and 481.43 μm, respectively. Hence, the particle size values in Biofield Energy Treated PLGA was increased by 8.97%, 8.79%,4.72%, and 6.61% at d10, d50, d90, and D(4,3), respectively compared to the control sample (Table 1). The specific surface area of the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA (0.0245 m2/g) was decreased by 6.84% compared with the control sample (0.0263 m2/g). Hence, it can be proposed that the Trivedi Effect®-Consciousness Energy Healing Treatment might reduce the internal molecular energy for increasing the particle size of PLGA sample. The increased particle size of a compound may help in enhancing the shape, appearance, and flow ability of that compound[39,40]. Thus, the Biofield Energy Treatment might improve the powder flow ability, the lower solubility of PLGA in the solvent. Lower solubility of the Biofield Energy Treated samplein water would be helpful to minimize the hydrolysis of the ester linkages in PLGA[2-5]. This improved quality would be a better choice for the pharmaceutical formulations and biomedical devices manufacturing industry using it as a raw material.

Table 1: Particle size distribution of the control and Biofield Energy Treated Polylactic-co-glycolic acid.

| Parameter | d10 (μm) | d50 (μm) | d90 (μm) | D(4,3)(μm) | SSA(m2/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 123.36 | 393.83 | 864.9 | 451.581 | 0.0263 |

| Biofield Treated | 134.42 | 428.42 | 905.69 | 481.43 | 0.0245 |

| Percent change* (%) | 8.97 | 8.78 | 4.72 | 6.61 | -6.84 |

d10, d50, and d90: particle diameter corresponding to 10%, 50%, and 90% of the cumulative distribution, D(4,3): the average mass-volume diameter, and SSA: the specific surface area.

*denotes the percentage change in the Particle size distribution of the Biofield Energy Treated sample with respect to the control sample.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Analysis

The thermal analysis of both control and Biofield Energy Treated samples has been performed to evaluate the impact of the Trivedi Effect® on the thermal behavior of PLGA. The thermograms of both the samples showed two endothermic peaks. The control PLGA sample showed the sharp endothermic peaks at 60.94°C and 335.11°C in the thermogram (Figure 2). Similarly, the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA sample showed the sharp endothermic peaks at 60.95°C and 328.4°C in the thermogram (Figure 2). The 1st endothermic peak was due to the evaporation of the trapped water molecule from the sample, whereas the 2nd large endothermic pick was due to the melting of PLGA. The observed DSC thermograms patterns were well matched with the literature data[1]. The evaporation and melting temperature of the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA were slightly altered by 0.02% and -2.00%, respectively compared with the control sample (Table 2). However, the latent heat of evaporation (ΔHevaporation) and latent heat of fusion (ΔHfusion) of the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA were significantly increased by 29.60% and 230.93%, respectively compared with the control sample (Table 2). Although the evaporation and melting temperature were altered, but the heat energy required by the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA for the evaporation and melting was significantly increased compared to the control sample. Therefore, it can be assumed that the thermal stability of the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA was increased compared to the control sample. Any change in the molecular chains, and the crystal structure influence the latent heat of fusion[41]. Therefore, Alice’s Biofield Energy Treatment could have disturbed the molecular chains and crystal structure of PLGA which lead to the increased thermal stability of the Biofield Energy Treated sample compared to the control sample.

Table 2: DSC data for both control and Biofield Energy Treated samples of Polylactic-co-glycolic acid.

| Sample | Melting point (°C) | ΔH(J/g) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Peak | 2nd Peak | Evaporation | Melting | |

| Control Sample | 60.94 | 335.11 | 5.54 | 66.54 |

| Biofield Energy Treated | 60.95 | 328.4 | 7.18 | 220.2 |

| % Change* | 0.02 | -2.00 | 29.60 | 230.93 |

ΔH: Latent heat of evaporation/fusion, *denotes the percentage change of the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA with respect to the control sample.

Figure 2: DSC thermograms of the control and Biofield Energy Treated Polylactic-co-glycolic acid.

Thermal Gravimetric Analysis (TGA)/ Differential thermogravimetric analysis (DTG)

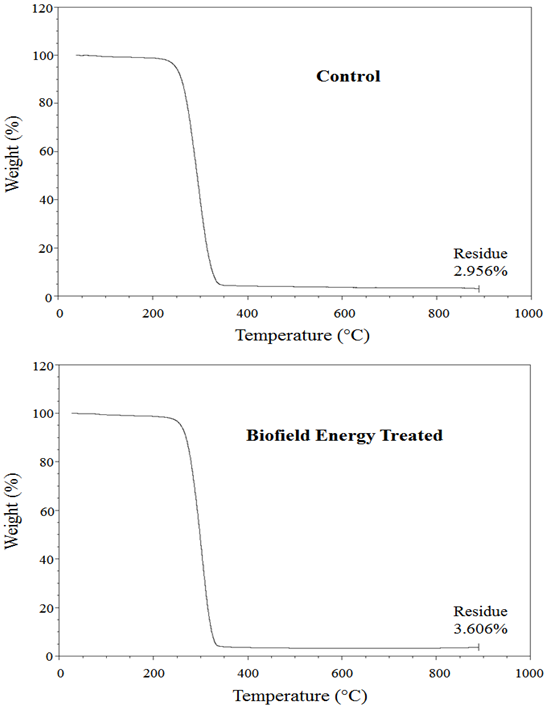

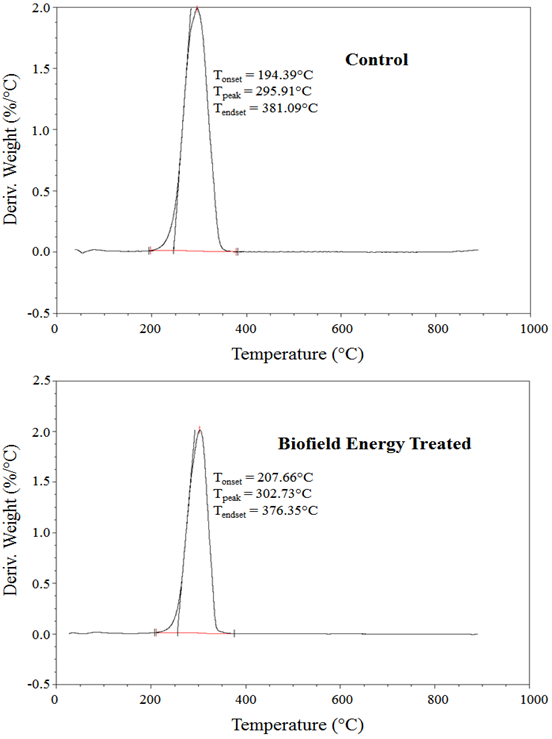

The TGA/DTG thermograms of the control and Biofield Energy Treated PLGA samples are displayed in Figures 3 and 4. Both the thermograms showed one step of the degradation process. The total weight loss in the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA (96.39%) was decreased by 0.67% compared with the control sample (97.04%). Therefore, the residue amount was 21.99% more in the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA compared to the control sample (Table 3).

Figure 3: TGA thermograms of the control and Biofield Energy Treated Polylactic-co-glycolic acid.

Figure 4: DTG thermograms of the control and Biofield Energy Treated Polylactic-co-glycolic acid.

Table 3: TGA/DTG data of the control and Biofield Energy Treated samples of Polylactic-co-glycolic acid.

| Sample | TGA | DTG Tmax (°C) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Total weight loss (%) | Residue % | ||

| Control | 97.04 | 2.96 | 295.91 |

| Biofield Energy Treated | 96.39 | 3.61 | 302.73 |

| % Change* | -0.67 | 21.99 | 2.30 |

*denotes the percentage change of the Biofield Energy Treated sample with respect to the control sample, Tmax = the temperature at which maximum weight loss takes place in TG or peak temperature in DTG.

Similarly, the DTG thermograms of the control and Biofield Energy Treated PLGA exhibited one sharp peak (Figure 4). The maximum thermal degradation temperature (Tmax) of the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA was increased by 2.30% compared with the control sample. Overall, TGA/DTG thermal analysis revealed that the thermal stability of the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA was increased compared with the control sample.

Conclusion

The Trivedi Effect®-Consciousness Energy Healing Treatment have a significant impact on the particle size, surface area, and thermal behaviors of PLGA. The particle size values of the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA powder sample at d10, d50, d90, and D(4,3) were increased by 8.97%, 8.79%, 4.72%, and 6.61%, respectively compared to the control sample. Therefore, the surface area of the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA was significantly decreased by 6.84% compared with the control sample. The ΔHevaporation and ΔHfusion of the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA were significantly increased by 29.60% and 230.93%, respectively compared with the control sample. The residue amount was 21.99% more in the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA compared to the control sample. The Tmax of the Biofield Energy Treated PLGA was increased by 2.3% compared with the control sample. The Trivedi Effect®-Consciousness Energy Healing Treatment might have introduced a new polymorphic form of PLGA which may show better powder flowability and minimise the hydrolysis of the ester linkages of PLGA. This improved quality of PLGA would be a better choice for the pharmaceutical formulations (i.e.,the drug like simvastatin, amoxicillin, vancomycin, and minocycline loaded PLGA nanoparticles) and manufacturing of biomedical devices, i.e., grafts, sutures, implants, surgical sealant films, prosthetic devices, micro and nanoparticles in the industry using it as a raw material.

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to Central Leather Research Institute, SIPRA Lab. Ltd., Trivedi Science, Trivedi Global, Inc., Trivedi Testimonials, and Trivedi Master Wellness for their assistance and support during this work.

References

- 1. Erbettan, C.D.C., Alves, R.J., Resende, J.M., et al. Synthesis and characterization of poly (d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) copolymer. (2012) J Biomater Nanobiotechnol 3: 208-225.

- 2. Pavot, V., Berthet, M., Rességuier, J., et al. Poly (lactic acid) and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) particles as versatile carrier platforms for vaccine delivery. (2014) Nanomedicine (London) 9(17): 2703-2718.

- 3. Shinde, A.J., More, H.N. Design and evaluation of polylactic-co-glycolic acid nanoparticles containing simvastatin. (2011) Int J Drug Dev Res 3(2): 280-289.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 4. Dissolvable plastic nanofibers could treat brain infections. Scientific Computing. (2013) Advantage Business Media. Retrieved 16-01-2018.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 5. Kashi, T.S., Eskandarion, S., Esfandyari-Manesh, M., et al. Improved drug loading and antibacterial activity of minocycline-loaded PLGA nanoparticles prepared by solid/oil/water ion pairing method. (2012) Int J Nanomedicine 7: 221-234.

- 6. Samadi, N., Abbadessa, A., Di Stefano, A., et al. The effect of lauryl capping group on protein release and degradation of poly (D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) particles. (2013) J Control Release 172(2): 436-443.

- 7. Jain, R.A. The manufacturing techniques of various drug loaded biodegradable poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) devices. (2000) Biomaterials 21(23): 2475-2490.

- 8. Gilding, D.K., Reed, A.M. Biodegradable polymers for use in surgery-polyglycolic/ poly(lactic acid) homo- and copolymers: 1. (1979) Polymer 20(12): 137-143.

- 9. Anderson, J.M., Shive, S.M. Biodegradation and biocompatibility of PLA and PLGA microspheres. (1997) Adv Drug Deliv Rev 28(1): 5-24.

- 10. Alexis, F. Factors affecting the degradation and drug-release mechanism of poly (lactic acid) and poly [(lactic acid)-co-(glycolic acid)]. (2005) Polym Int 54(1): 36-46.

- 11. Hyon, S.H., Jamshidi, K., Ikada, Y. Effects of residual monomer on the degradation of DL lactide polymer. (1998) Polym Int 46(3): 196-202.

- 12. Trivedi, M.K., Mohan, R., Branton, A., et al. Evaluation of biofield energy treatment on physical and thermal characteristics of selenium powder. (2015) J Food Nutr Sci 3: 223-228.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 13. Trivedi, M.K., Branton, A., Trivedi, D., et al. Fourier transform infrared and ultraviolet-visible spectroscopic characterization of biofield treated salicylic acid and sparfloxacin. (2015) Nat Prod Chem Res 3: 186.

- 14. Trivedi, M.K., Branton, A., Trivedi, D., et al. Mass spectrometric analysis of isotopic abundance ratio in biofield energy treated thymol. (2016) Frontiers in Applied Chem 1: 1-8.

- 15. Trivedi, M.K., Mohan, T.R.R. Biofield energy signals, energy transmission and neutrinos. (2016) Am J Modern Physics 5(6): 172-176.

- 16. Rubik, B., Muehsam, D., Hammerschlag, R., et al. Biofield science and healing: history, terminology, and concepts. (2015) Glob Adv Health Med 4(Suppl): 8-14.

- 17. Oschman, J. Energy Medicine in Therapeutics and Human Performance. (2003) Philadelphia: Butterworth Heinemann 1-12.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 18. Barnes, P.M., Bloom, B., Nahin, R.L. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. (2008) Natl Health Stat Report 12: 1-23.

- 19. Koithan M. Introducing complementary and alternative therapies. (2009) J Nurse Pract 5(1): 18-20.

- 20. Trivedi, M.K., Patil, S., Tallapragada, R.M. Effect of biofield treatment on the physical and thermal characteristics of Silicon, Tin and Lead powders. (2013) J Material Sci Eng 2:125.

- 21. Trivedi, M.K., Patil, S., Tallapragada, R.M. Effect of bio field treatment on the physical and thermal characteristics of vanadium pentoxide powders. (2013) J Material Sci Eng S 11: 001.

- 22. Trivedi, M.K., Branton, A., Trivedi, D., et al. Evaluation of isotopic abundance ratio in biofield energy treated nitrophenol derivatives using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. (2016) Am J Chem Engg 4(3): 68-77.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 23. Trivedi, M.K., Branton, A., Trivedi, D., et al. Determination of isotopic abundance of 13C/12C or 2H/1H and 18O/16O in biofield energy treated 1-chloro-3-nitrobenzene (3-CNB) using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. (2016) Sci J Anal Chem 4: 42-51.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 24. Trivedi, M.K., Branton, A., Trivedi, D., et al. Physical and structural characterization of biofield treated imidazole derivatives. (2015) Nat Prod Chem Res 3: 187.

- 25. Trivedi, M.K., Tallapragada, R.M., Branton, A., et al. Characterization of physical, spectral and thermal properties of biofield treated 1,2,4-triazole. (2015) J Mol Pharm Org Process Res 3: 128.

- 26. Nayak, G., Altekar, N. Effect of a biofield treatment on plant growth and adaptation. (2015) J Environ Health Sci 1: 1-9.

- 27. Trivedi, M.K., Branton, A., Trivedi, D., et al. Evaluation of plant growth regulator, immunity and DNA fingerprinting of biofield energy treated mustard seeds (Brassica juncea). (2015) Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries 4: 269-274.

- 28. Trivedi, M.K., Branton, A., Trivedi, D., et al. Assessment of antibiogram of multidrug-resistant isolates of Enterobacter aerogenes after biofield energy treatment. (2015) J Pharma Care Health Sys 2: 145.

- 29. Trivedi, M.K., Branton, A., Trivedi, D., et al. Antibiogram typing of biofield treated multidrug resistant strains of Staphylococcus species. (2015) Am J Life Sci 3: 369-374.

- 30. Trivedi, M.K., Branton, A., Trivedi, D., et al. Agronomic characteristics, growth analysis, and yield response of biofield treated mustard, cowpea, horsegram, and groundnuts. (2015) Int J Genetics Genomics 3: 74-80.

- 31. Trivedi, M.K., Branton, A., Trivedi, D., et al. Evaluation of plant growth, yield and yield attributes of biofield energy treated Mustard (Brassica juncea) and Chick pea (Cicer arietinum) Seeds. (2015) Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries 4: 291-295.

- 32. Trivedi, M.K., Patil, S., Shettigar, H., et al. The potential impact of biofield treatment on human brain tumor cells: A time-lapse video microscopy. (2015) J Integr Oncol 4: 141.

- 33. Trivedi, M.K., Patil, S., Shettigar, H., et al. in vitro evaluation of biofield treatment on cancer biomarkers involved in endometrial and prostate cancer cell lines. (2015) J Cancer Sci Ther 7: 253-257.

- 34. Desktop X-ray Diffractometer “MiniFlex+”. (1997) The Rigaku Journal 14: 29-36.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 35. Zhang, T., Paluch, K., Scalabrino, G., et al. Molecular structure studies of (1S,2S)-2-benzyl-2, 3-dihydro-2-(1Hinden-2-yl)-1H-inden-1-ol. (2015) J Mol Struct 1083: 286-299.

- 36. Langford, J.I., Wilson, A.J.C. Scherrer after sixty years: A survey and some new results in the determination of crystallite size. (1978) J Appl Cryst 11(2): 102-113.

- 37. Trivedi, M.K., Sethi, K.K., Panda, P., et al. A comprehensive physicochemical, thermal, and spectroscopic characte-rization of zinc (II) chloride using X-ray diffraction, particle size distribution, differential scanning calorimetry, thermogravimetric analysis/differential thermogravimetric analysis, ultraviolet-visible, and Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy. (2017) Int J Pharm Investig 7(1): 33-40.

- 38. Trivedi, M.K., Sethi, K.K., Panda, P., et al. Physicochemical, thermal and spectroscopic characterization of sodium selenate using XRD, PSD, DSC, TGA/DTG, UV-vis, and FT-IR. (2017) Marmara Pharm J 21(2): 311-318.

- 39. Mosharrof, M., Nystrom, C. The effect of particle size and shape on the surface specific dissolution rate of microsized practically insoluble drugs. (1995) Int J Pharm 122(1-2): 35-47.

- 40. Buckton, G., Beezer, A.E. The relationship between particle size and solubility. (1992) Int J Pharm 82(3): R7-R10.

- 41. Zhao, Z., Xie, M., Li, Y., et al. Formation of curcumin nanoparticles via solution-enhanced dispersion by supercritical CO2. (2015) Int J Nanomedicine 10: 3171-3181.