Calcium Chloride and Vitamin D Bioavailability from Fortified Beverages in Wistar Rats.

Mallorye D. Lovett and Jonathan C. Allen*

Affiliation

- Department of Food, Bioprocessing, and Nutrition Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA

Corresponding Author

Jonathan C. Allen, Department of Food, Bioprocessing, and Nutrition Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27695-7624, USA, Tel: 919-513-2257; E-mail: jon_allen@ncsu.edu

Citation

Lovett, M.D., et al. Calcium Chloride and Vitamin D Bioavailability from Fortified Sports Drink in Wistar Rats (2014) Int J Food Nutr Sci 1(1): 6-12.

Copy rights

© 2014 Allen, J.C. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Abstract

Calcium and vitamin D play a critical role in the prevention of metabolic diseases includingosteoporosis, osteomalacia, and stress fractures, butaverage intake is below the RDA. The objective of this study was to test a water-soluble form of vitamin D andcalcium chloride as fortifiers for sports drink solution using a rat bioavailabilityassay.Vitamin D fortifying ingredient was prepared as a spray-dried complexwith bovine beta-lactoglobulin. Flavored beverages were formulated with various ratios of calcium and vitamin D in a 4x4factorial design. Female Wistar rats were housed under incandescent lighting for a 4-week depletion phase, then given drink formulations with low calcium, low vitamin D diet for anadditional six weeks. Blood and femur bones were analyzed. The fortified drink solutions could be accurately formulated tocontain calcium chloride at 0, 1, 2 and 2.5 g Ca/L with palatability to rats. Serum vitamin D wassignificantly greater (p< .0001) in rats receiving the vitamin D-fortified drinks (10, 20, and 40 μg/L), but no dose-response was evident.Water-soluble vitamin-D can successfully fortify aqueous products with this fat-solublevitamin. Regular consumption of flavored sports drinkfortified with calcium and vitamin D may significantly increase dietary calcium and vitaminD.

Introduction

Vitamin D plays a critical role in the homeostatic control of calcium and phosphorus. Adequate intake of vitamin D increases the efficiency of intestinal calcium absorption by increasing intracellular calbindin D, which facilitates skeletal development[1]. Calcium and vitamin D prevent metabolic diseases including osteoporosis, osteomalacia, rickets, and the stress fracture component of the female athlete triad. Optimizing calcium and vitamin D intake are recommended components in treatment and prevention of the female athlete triad[2]. Epidemiological research indicates that average intakes of these nutrients are well below the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA), and greater intake has been correlated with a reduction in fractures, prevention of osteoporosis, and increased bone mass[3]. The vitamin D and calcium RDAs were established in 2010 at levels higher than earlier Adequate Intake (AI) values[4], but that generally has not translated to more vitamin D fortification or greater intake of calcium. For example, the vitamin D RDA was set to 15 μg/day for adults under 70 years, rather than the AI of 5 μg/day for adults under 50 years. Supplementation above the current RDA yielded a decrease in fractures[5-7]. These research studies lay the framework for more fortification of various food products with calcium and vitamin D. However, fortification of low fat food products or non-fat beverages with currently available forms of vitamin D often results in problems with stability of vitamin D in the food, binding of this lipophilic nutrient to plastic containers, or poor bioavailability from emulsions and suspensions. Our research program has aimed at reduction or elimination of these problems.

We have developed a method for creating a water-soluble fortifier for vitamin D[8]. Beta-lactoglobulin (BLG) has many functional properties including a transportation mechanism of molecules such as vitamins. BLG tightly binds to retinol (vitamin A), cholesterol and vitamin D[9]. Lipophilic vitamins structurally bind to the hydrophobic core of the BLG molecule. Previous studies suggest that BLG has a higher affinity for vitamin D compared to other lipophilic vitamins[10]. Spray drying is an application that can facilitate the binding of beta-lactogobul and lipophilic vitamins for use as a fortifier of low fat foods[11,12]. Because this complex can form a water-soluble form of vitamin D, it can be paired with calcium in aqueous solutions that use calcium chloride because of its highly ionized state that may promote calcium absorption. The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of the water-soluble form of vitamin D and calcium chloride as fortifiers for aqueous sports drink solutions with a rat bioavailability assay.

Materials and Methods

β-lactoglobulin and vitamin D complex preparation

BioPure β-lactogolubin was purchased from Davisco Foods International, Inc. (LeSueur, MN). Vitamin D3 (MW 384.65) and vitamin D2 (MW 396.65) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO) and Roche Vitamins Inc. (Nutley, NJ), respectively. Four hundred mL of 2% w/v of β-lactoglobulin (~8g) in DI water was prepared. The solution was mixed on a magnetic stirring plate at low speed (2) to prevent foaming until a homogenous clear solution was obtained. All work conducted with vitamin D was performed under dim yellow light and used amber containers or glassware enclosed in aluminum foil to prevent degradation of vitamin D from direct light exposure.

The complex was spray dried on a pilot scale dryer (Annhydro, Denmark). Prior experiments determined optimum drying conditions to protect both BLG and vitamin D to be 120°C inlet air temperature and 68-70°C outlet temperature. The system was flushed with deionized water via a MasterFlex peristaltic pump (Model 7518-10, Cole-Parmer Instrument Co., Vernon Hills, IL) to stabilize the unit before the solution could be added. The protein-vitamin stock solution was pumped into the machine at a flow rate ~2 mL/min while continuously monitoring the inlet and outlet temperatures to ensure that heat denaturation would not occur. The powder was weighed, placed in an amber vial with aluminum foil surrounding the exterior, flushed with nitrogen, and stored in the freezer (-20°C) for further analyses.

HPLC analysis for vitamin D content

The percent recovery was calculated for the vitamin D in the spray-dried powder. The vitamin D3 content of the β-lactoglobulin- vitamin D complex was determined by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) using vitamin D2 as internal standards as described by Liu[13]. HPLC analyses were performed on a Waters Millipore Automated Gradient Controller with UVIS linear detector and a manual loading injector (Waters Associates, Milford MA). Reversed-phase 4.6 x 250nm Vydac TP201 C18, 5 μm column with a guard column (Vydac, Hesperia, CA) was used with a mobile phase consisting of acetonitile/ ethyl acetate/chloroform (88:8:4; v/v/v) at a consistent flow rate of 1 mL/min. Methanol was used to wash and equilibrate the column before and after each sample injection. A wavelength of 264 nm was used to quantify the results and Dynamax Software Package (Waters Associates) was used to integrate the peak areas of vitamin D. Fifty μL of the extracted sample was injected into the HPLC system. Standards were injected before injecting the unknown samples. Area under the curve (AUC) was recorded for vitamin D2 and D3, respectively, where vitamin D2 AUC was used as an internal standard. The retention time was also obtained and recorded for the peak values under both vitamins.

Rat bioavailability assay

The North Carolina State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved the protocol for this study. Female Wistar rats (Charles River Laboratory, Raleigh, NC) were individually housed under incandescent lighting with no UV-B component with a 12- hour light/dark cycle. Rats were randomly divided into 16 treatment groups and 4 control groups. Immediately after arrival five of the weanling (4-week old) rats were sacrificed for baseline data. The remaining rats were made deficient in vitamin D for 4 additional weeks, by feeding a modified AIN-93G diet with normal calcium (5.0 g Ca/kg) level and lower vitamin D (0.11g/kg), as analyzed after the study concluded. After completion of the reduction phase, an additional five rats were sacrificed and serum was collected and stored for later measurement of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol (25-OH D3).

A 4X4 factorial design was utilized to divide the animals into subgroups for the drinking water supplementation. The concentrations approached or bracketed our estimate of intake from normal dietary AIN 93G diet, equivalent to 2.88 g Ca/L and 14.4 μg vitamin D3/L. These values indicate the estimated daily requirement (EDR) for calcium and vitamin D respectively, based upon previous research conducted in our laboratory that measured feed and water intake in rats of comparable ages that were fed AIN 93G diet with standard levels of vitamins and minerals. The rats received the fortified water for 6 weeks, or until approximately 14 weeks of age. The vitamin D contents of the sports drinks were formulated to be 0, 10, 20, or 40 μg/L. Calcium concentrations were 0, 1, 2, 2.5g/L as CaCl2(Tetra Technologies, The Woodlands, TX). The treatments were given identifying letters as shown in Table 1 with five rats in each treatment group. Fruit flavor and non-caloric sweetener was added to increase palatability. For the duration of the vitamin D repletion stage, animals' drink and food intake were recorded and weight was obtained twice per week. Calcium intake for the 6-week repletion period was calculated for food and water (weights of offering - refusals on weekly basis) x calcium content in food and water[11]. Rats were sacrificed with a ketamine (650 mg/100 g body weight) + xylazine (140mg/100 g body weight) anesthetic to achieve unconsciousness, followed by exsanguination. Blood was removed by cardiac puncture and serum vitamin D was determined by ELISA (Octeia 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D ELISA Kit, IDS Inc., Fountain Hills, AZ) as described below.

Bone assay for calcium analysis

The left femurs were weighed and measured. The right femurs were removed, ashed and analyzed for calcium content. All work pertaining to assay of bone was conducted under the fume hood. Prior to analysis of collected bones, test tubes, glass ware and crucibles were acid-washed to remove all foreign material and minerals. The left femur bones were cleaned manually by removing accessible excess tissue. The femurs were soaked overnight in a test tube containing 100% ethanol; solvent was discarded, then the bones were soaked in chloroform overnight to ensure that all lipid tissue material was removed from the femur bones. Solvent was discarded and the bones air-dried for approximately five minutes under the fume hood.

Table 1. Body weight, food and drink intake, and bone measurement parameters by treatment group1.

| Group | [Ca] in Drink (g/L) | [Vit.D]in Drink (µg/L) | Final Mean Body Weight (g) | Ashed bone weight (g) | Total Drink Intake (mL) | Total Food Intake (g) | Ca in Bone Ash (%) | Mid width (mm) | Joint width (mm) | Length (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 0 | 281.03 | 0.29 | 1,696 | 660 | 43.65 | 2.46 | 5.62 | 31.98 |

| B | 1.0 | 0 | 255.73 | 0.29 | 1,561 | 600 | 55.42 | 2.14 | 5.53 | 33.82 |

| C | 2.0 | 0 | 263.48 | 0.30 | 1,363 | 631 | 43.24 | 2.52 | 6.08 | 32.30 |

| D | 2.5 | 0 | 283.88 | 0.31 | 1,366 | 623 | 49.34 | 2.63 | 6.17 | 32.82 |

| E | 0 | 10 | 286.73 | 0.28 | 1,601 | 664 | 45.47 | 2.44 | 6.02 | 31.90 |

| F | 1.0 | 10 | 266.95 | 0.28 | 1,484 | 601 | 47.34 | 2.52 | 5.86 | 31.48 |

| G | 2.0 | 10 | 274.38 | 0.30 | 850 | 607 | 51.70 | 2.42 | 5.76 | 32.16 |

| H | 2.5 | 10 | 259.25 | 0.28 | 921 | 565 | 57.28 | 2.72 | 5.94 | 31.98 |

| I | 0 | 20 | 290.30 | 0.27 | 1,647 | 645 | 52.62 | 2.78 | 6.32 | 31.10 |

| J | 1.0 | 20 | 280.43 | 0.27 | 1,319 | 651 | 46.02 | 2.66 | 6.16 | 31.56 |

| K | 2.0 | 20 | 250.30 | 0.30 | 832 | 619 | 46.50 | 2.52 | 6.04 | 31.76 |

| L | 2.5 | 20 | 270.20 | 0.29 | 999 | 600 | 52.29 | 2.60 | 6.00 | 31.10 |

| M | 0 | 40 | 286.23 | 0.26 | 1,660 | 614 | 63.15 | 2.94 | 6.06 | 31.68 |

| N | 1.0 | 40 | 285.00 | 0.29 | 977 | 655 | 52.33 | 2.84 | 6.62 | 34.62 |

| O | 2.0 | 40 | 216.83 | 0.26 | 710 | 589 | 46.03 | 2.68 | 5.58 | 30.83 |

| P | 2.5 | 40 | 259.75 | 0.28 | 890 | 589 | 49.26 | 2.70 | 6.42 | 32.90 |

1Calcium and vitamin D intake from the fortified beverage and diet had no significant effect on any of the bone parameters as determined by one-way analysis of variance (overall P > 0.05).

The femurs were placed in pre-weighed, acid-washed, ceramic crucibles, weighed and ashed as follows. The bones were placed in the muffle furnace at 100°C for 8-12 h to remove excess moisture and cooled in desiccators. The dry weight was obtained and the cooled crucibles were placed back into the muffle furnace at 649°C for 24 h, and cooled 8 h. The crucibles containing the ash were re-weighed. The ashed material was transferred to a test tube and dissolved in 10 ml of 3 N HCl and diluted 1:1000 using 0.5% lanthanum in 0.1 N HCl. Atomic absorption spectrophotometry (Perkin Elmer Model 3100, Norwalk, CT) was utilized to obtain calcium content from the bone ash. Ash data were expressed as percent of dry defatted bone weight.

Bone strength test

Mechanical properties of the rats' femurs were determined with an Instron Universal Testing Instrument (Model 1122 Instron, Canton, MA). The right femurs were dissected from the body and visual soft tissue and muscle were removed from the bone. The bones were individually sealed in plastic bags and labeled and stored at -4°C until needed for strength testing. The femurs were thawed and three measurements (mid width, joint width, and length, all measured in millimeters) were ascertained with electronic calipers, and the three point bending test was performed.

Serum analysis for calcium and vitamin D

At the point of sacrifice, blood samples were collected in 4 ml Vacutainer tubes, coated with clot activator. The samples were allowed to rest for 30 minutes at room temperature and centrifuged at 760 x g for 15 minutes. The serum was collected in amber vials and stored at -20°C until analyzed. The serum samples were diluted 1:50 using 0.5% lanthanum in 0.1N HCl and calcium content was determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry. The Octeia 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D Elisa Kit (IDS Inc., Fountain Hills, AZ) used to analyze serum 25-OH vitamin D is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for analyzing 25-OH vitamin D status in humans. We verified reactivity in rat serum in a preliminary experiment. For this ELISA, 25 μl of each calibrator, control and sample were added to polypropylene test tubes. One mL of 25-OH D3 biotin solution was added. Each test tube was vortexed 10 seconds and 200 μL of each diluted calibrator; control and sample were added to the appropriate well of the antibody-coated plate in duplicate. The plate was the sealed and incubated at 18-25°C for 2 hours. Next, the plates were washed manually three times with 250 μL of buffer solution provided in the kit and emptied. Two hundred μL of enzyme conjugate was added to each well and incubated at 18-25°C for 30 minutes. The manual wash step was repeated, and 200 μL of tetramethylbenzidine substrate was added to each well using a multichannel pipette. The plate was again sealed and incubated at 18-25°C for 30 minutes. One hundred μL of 0.5 M HCl was added to each well with a multichannel pipette to stop the reaction. Within 30 minutes of adding the 0.5 M HCl the absorbency was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Electron Corporation, Vantaa, Finland).

Statistical methods

SAS software (Cary, NC) was used for the statistical analysis of the data. Correlation analysis compared calcium and vitamin D in water, calcium and vitamin D in food to other dependent variables. Differences among groups for measurement of nutrient intake were tested with one-way Analysis of Variance using an overall significance probability of α = 0.05. Rat serum data were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with Scheffe's post hoc test. Relying on the F-test in the ANOVA for analysis of the 4 x 4 factorial designs minimized the used of multiple comparison post hoc tests and use of individual treatment standard errors for unplanned comparisons and resulting Type 1 errors[14].

Results

Calcium and vitamin D intake

After spray drying, the vitamin D-protein complex was analyzed and quantified by HPLC analysis. The quantity of vitamin D measured in the protein vitamin complex was 102% of the theoretical value from the formulation. An average concentration of vitamin D in the BLG complex was calculated and used to design animal diets. Additionally, the vitamin D content of the diet was analyzed. The results showed that vitamin D was present in the normal diet at 0.32 mg/kg (compared to label specification of 0.25 mg/kg), and was also present in the vitamin D deficient diet at 0.11 mg/kg. The measured concentrations in the diets were used in the calculation of total vitamin D intake.

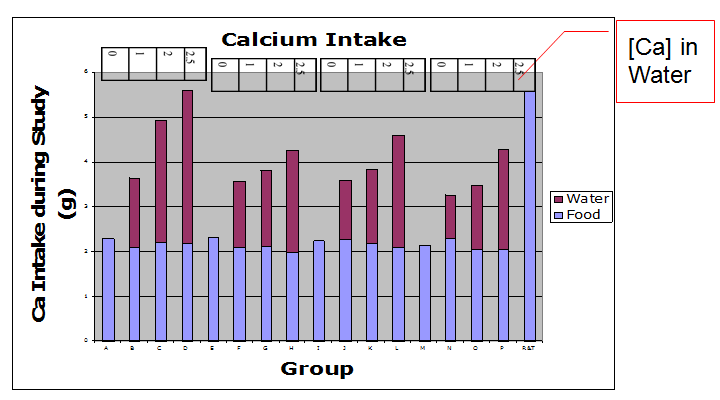

Calcium intake for the 6- week repletion period as calculated from food and water offerings minus refusals are shown in Figure 1. Groups R and T received the positive control diet and tap water. Group D (2.5 g/L Ca; 0 vitamin D in drink) consumed the greatest amount of calcium via beverage and diet consumption. Furthermore, the animals in the group D were able to consume an amount of calcium via beverage and diet equivalent to the positive control (calcium intake from feed only). The calcium via food intake was consistent among all treatment groups. The highest mean calcium intake from water was seen in treatment groups B, C, and D (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Calcium Intake: Calcium intake for the 6-week repletion period was calculated for food& water (weights of offering - refusals on weekly basis) x Ca content infood & water. Groups R and T received the positive control diet and tapwater. N = 5 rats per treatment group.

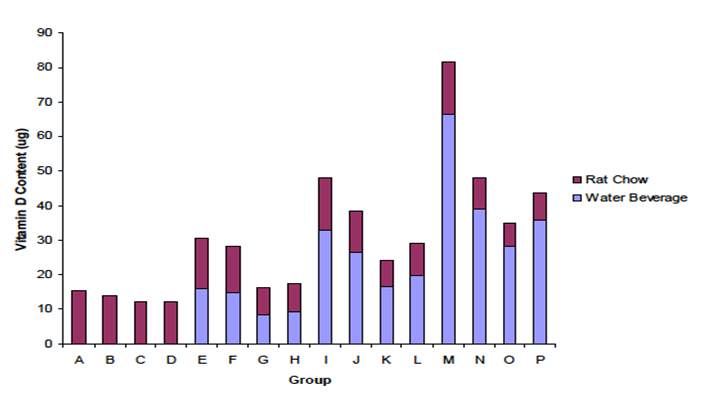

Vitamin D intake for the 6-week repletion period was calculated for water (weights of offering-refusals on weekly basis) x vitamin D content in water. Groups A, B, C, and D had no vitamin D from fortified sports drink (Figure 2). However, as previously mentioned, vitamin D was contained in the vitamin D deficient diet in the amount of 0.11 mg/kg.

Figure 2: Vitamin D Intake: Vitamin D intake for the 6-week repletion period was calculated for water (weights of offering - refusals on weekly basis) x vitamin D content in water. Group letters identification as in Table 1. N = 5 rats per treatment group.

Serum calcium, serum vitamin D and serum protein

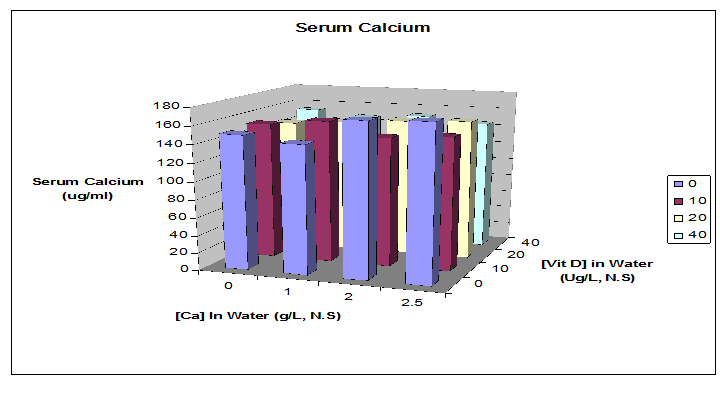

Serum calcium was analyzed by a 2-way ANOVA with calcium and vitamin D intakes as main effects. Data among all treatment groups were not significantly different from each other (Figure 3). Serum vitamin D concentration in all treatments was adequate to compensate for low Ca intake. The fact that serum Ca did not change suggests that there may be no treatment effects observed for other biological functions of calcium, such as maintaining bone mass or bone Ca content. Lower levels of vitamin D in the diet and serum might have lowered serum calcium concentration and bone Ca measurements.

Figure 3: Serum Calcium: Serum calcium (Ca & Vit D intakes) was analyzed by a 2-way ANOVA. Data show no significant differences between groups. Serum vitamin D in all treatments was adequate to compensate for low Ca intake. The fact that serum Ca did not change can also be used as the explanation for no treatment effects on bone mass or bone Ca. N = 5 rats per treatment group.

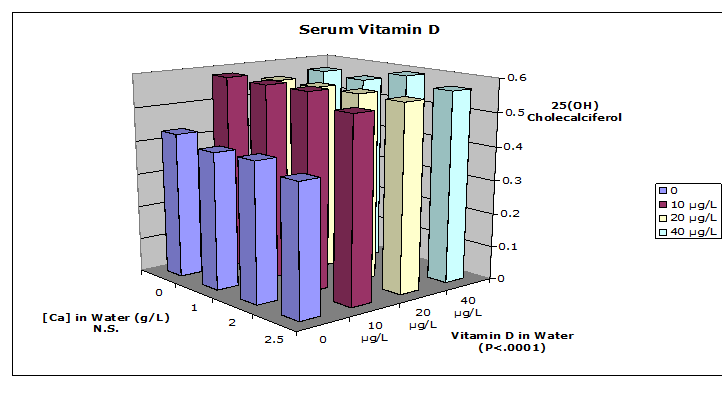

Serum 25-OH D3 analysis from competitive ELISA is shown in Figure 4. After the depletion phase the animals' serum 25-OH D3 values were reduced, but the concentration was restored to varying extents in the 6-wk repletion phase of the experiment. Groups receiving no vitamin D in water were significantly different from the other groups (P < 0.05). A dose response among treatments was not evident among the groups consuming drink with 10, 20 or 40 μg/L of vitamin D. The ELISA assay used recognizes vitamin D2 75% as effectively as vitamin D3, however the rats in this study were not fed any vitamin D2.

Figure 4: Serum 25-OH Vitamin D: Serum 25-OH vitamin D was analyzed by competitive ELISA (IDS Inc., Fountain Hills,AZ). Data were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with Scheffe's post hoc test. Groups receiving no vitamin D in water were significantly different from the other groups. N = 5 rats per treatment group.

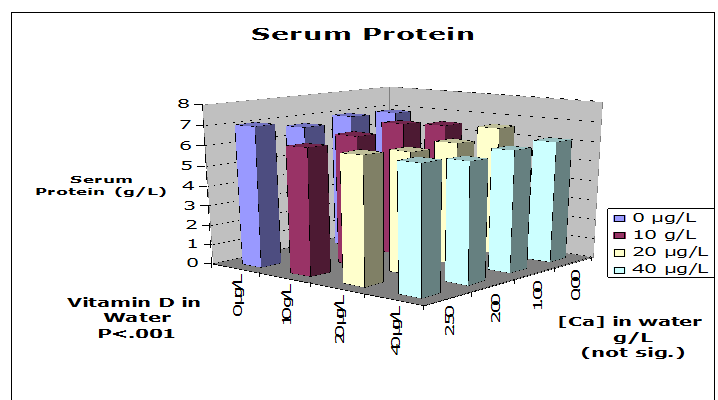

Serum protein was measured because total serum calcium concentration can be influenced by the quantity bound to protein, as well as the ionized calcium concentration that is controlled by vitamin D and parathyroid hormone. Figure 5 shows that serum protein was not significantly different among groups with various levels of vitamin D intake. However, the serum protein concentration of the rats tended to increase as the amount of vitamin D increased within the different levels of calcium.

Figure 5: Serum Protein: Serum protein was not significantly different among the various treatment groups. However, high concentration of vitamin D correlated with increased serum protein. N = 5 rats per treatment group.

Serum 25-OH D3 in rats fed control diet for 4 weeks was 55.24 ±15.24 nmol/L. Serum 25-OH D3 in rats fed low vitamin D3 diets for 6 weeks were 91.15 ± 9.26 nmol/L.

Bone parameters and correlations

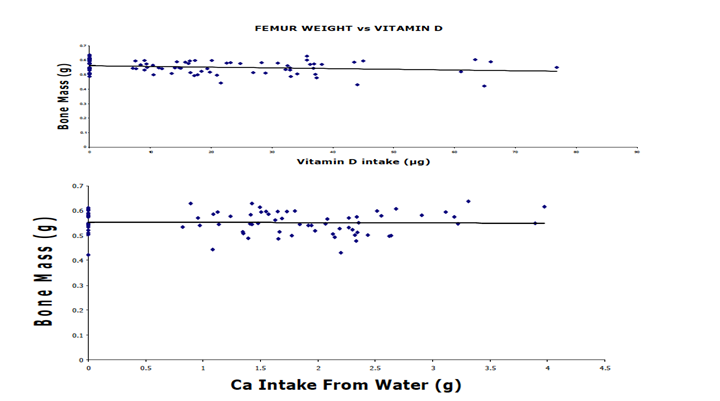

As illustrated in Table 1, the final mean body weights were not significantly different among all groups. Bone ash weight was derived from drying and ashing the femur bones of the rats. The average ash weights were not significantly different among the groups. Additionally, beverage intake was measured to determine the total intake of calcium and vitamin D. Water consumption was greatest among those groups whose water was composed of no or the lowest amount of CaCl2. The percent of Ca in the bone ash did not significantly differ among treatment groups. The total intake of Ca from fortified beverages did not correlate with percentage of Ca in bone (R = - 0.109). Furthermore, the femur mass did not correlate with the intake of either calcium or vitamin D (P > 0.05) (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Correlation between Bone Mass and Vitamin D (top panel) and Calcium (bottom panel) Intake among all rats: Femur weights were not significantly affected by the vitamin D content in water. Femur weights were not significantly affected by the ratio of calcium intake, regardless of vitamin D content in water. Low calcium intake of bone was compensated for by vitamin D. The slope of the regression line was not significantly different from zero in either panel. Each point represents an individual rat.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of a water-soluble form of vitamin D and calcium supplementation via an aqueous solution on various bone parameters in Wistar rats fed a vitamin D deficient diet. β-lactoglobulin has been shown to bind with vitamin D[9,10]. Vitamin D activity was maintained by using a carbohydrate carrier during spray drying[12,15]. This complex has been shown as an effective fortifier of aqueous solutions[15,16]. Previous research[16] also showed the calcium sensory threshold for humans to be 70 mg/L of CaCl2 (25 mg/L of Ca) in water, and about 10 fold higher in flavored water, which is less than the concentration used in all of the calcium fortified beverages in this study. The present data confirmed that proposed vitamin D concentration for flavored water or sport drink was achievable using the protein complex to make a water- soluble form of vitamin D.

The Wistar rat model system was used to determine the bioavailability of the vitamin D and calcium in such solutions. The experiment was designed to supply vitamin D only in the flavored drinking water, and reduce the calcium level in the diet to a point where vitamin-D dependent calcium absorption would be needed to maintain normal bone mass. However, the vitamin-D deficient diet was analyzed and found to have contained vitamin D. Thus, the baseline vitamin D intake from diet, although only one third as high as control diet, provided more vitamin D than the water in most treatments.

Bone strength has been correlated with bone mass and bone quality[17]. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation in a vitamin D deficient diet did not result in a stimulated increase of food or beverage intake as seen in other supplementation studies[18]. Supplementation with the fortified aqueous solution containing calcium and vitamin D did not result in a significant difference in live weight[19], contrary to other studies[20]. Moreover, supplementation with the fortified beverages had no significant treatment effect on serum calcium. The aqueous vitamin D supplementation significantly increased serum 25-OH vitamin D in this study (P < 0.01). However, the lack of dose-response among the different levels of vitamin D in the drink suggests that Wistar rats may have a homeostatic mechanism controlling serum 25-OH vitamin D concentrations. In humans, "Increasing intake of vitamin D results in higher blood levels of 25-OHD, although perhaps not in a linear manner"[4].

The low calcium intake via food and beverage may have resulted in an increased serum PTH and stimulated more efficient intestinal calcium absorption[18,21,22]. The adequate levels of serum calcium may also have facilitated consistent bone strength and length among the different treatment groups. Uchikura[23], reported that female Wistar rats' bone mass peaked at 10-12 months. Therefore, this study's duration may have not covered time periods when bone mass differences with greater sensitivity to dietary calcium or vitamin D might be observed in this particular species or strain.

Prevention of bone loss via supplementation with calcium and vitamin D was evident. The results of the present study suggest that calcium and vitamin D work synergistically to maintain bone mass in animals, as similarly seen in human studies[24,25]. Data from the present study clearly illustrate that calcium chloride and a soluble form of vitamin D could be used as fortifiers of flavored sports drink-type solutions. Furthermore, supplementation with calcium and vitamin D was able to maintain serum calcium and vitamin D levels to prevent negative impact on bone mass. Sufficient amounts of calcium and vitamin D via the diet are important to prevent degenerative bone diseases, such as osteoporosis and osteomalacia in the elderly and stress fractures in young athletes. Nevertheless, there is still limited research that investigates the use of a water-soluble form of vitamin D as a fortifier. Currently calcium and vitamin D are used as fortifiers in dairy products[26]. However, the water-soluble form of vitamin D and calcium chloride could be used in a multitude of food applications, even in the absence of fat. Adding these nutrients to sports drinks could target the young endurance athlete populations that might be susceptible to the bone microstructure problems of the female athlete triad and at risk for osteoporosis later in life[27].

Conclusion

This research has shown that the vitamin D and BLG complex is a good vitamin D carrier for use in aqueous solutions. A water-soluble form of vitamin D can be used to fortify aqueous products to improve vitamin D status and help facilitate the uptake of calcium. Moreover, in this experiment regular consumption of flavored sports drink fortified with calcium and vitamin D was shown to significantly increase dietary calcium and vitamin D intake. Even though the intakes varied significantly, there were no significant effects on serum calcium concentration or bone parameters. HPLC analyses of diet and serum 25-OH D3 suggests that all of the rat groups had enough vitamin D to adapt to low calcium intake. Nonetheless, the aqueous vitamin D significantly increased serum 25-OH D3, a primary indicator of vitamin D status, compared to groups that had no vitamin D in the drinking water.

References

- 1. Holick, M. F. The vitamin D epidemic and its health consequences. (2005) J Nutr 135(11): 2739S-2748S.

- 2. Nazem, T.G., Ackerman, K.E. The female athlete triad. (2012) Sports Health 4(4): 302-311.

- 3. Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A., Giovannucci, E., Willett, W.C., et al. Estimation of optimal serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D for multiple health outcomes. (2006) Am J Clin Nutr 84(1): 18-28.

- 4. Ross, C.A., Taylor, C. A., Yaktine, A. L., et al. Dietary Reference Intakes. Calcium, Vitamin D. (2011) Washington DC: National Academies Press (US).

- 5. Holick, M.F. Vitamin D requirements for humans of all ages: new increased requirements for women and men 50 years and older. (1998) Osteoporos Int 8(2): S24-S29.

- 6. Hollis, B.W., Wagner, C.L. Assessment of dietary vitamin D requirements during pregnancy and lactation. (2004) Am J Clin Nutr 79(5): 717-726.

- 7. Vieth, R., Bischoff-Ferrari, H., Boucher, B.J., et al. The urgent need to recommend an intake of vitamin D that is effective. (2007) Am J Clin Nutr 85(3): 649-650.

- 8. Swaisgood, H., Wang, Q., Allen, J. A Protein Ingredient for Carrying Lipophilic Nutrients in Low Fat Foods. (2001).

- 9. Kontopidis, G., Holt, C., Sawyer, L. Invited review: β-lactoglobulin: binding properties, structure and function. (2004) J Dairy Sci 87(4): 785-796.

- 10. Wang, Q., Allen, J.C., Swaisgood, H.E. Binding of vitamin D and cholesterol to β-lactoglobulin. (1997) J Dairy Sci. 80(6): 1054-1059.

- 11. Liu,Y., Shaw J.J., Swaisgood, H. E., et al. Bioavailability of oil-based and β-lactoglobulin-complexed vitamin A in a rat model. (2013) ISRN Nutr.

- 12. Ameri, M., Maa, Y.F. Spray drying of biopharmaceuticals: stability and process considerations. (2006) Drying Tech. 24(6): 763-768.

- 13. Lui, Y. Beta-lactoglobulin complexed vitamins A and D in skim milk: shelf life and bioavailability (PhD Dissertation) (2003) Raleigh, NC: North Carolina State University.

- 14. Saville, D.J. Multiple comparison procedures: The practical solution. (1990) Amer Statistician 44(2): 174-180.

- 15. Reynolds, R. Spray drying of β-lactoglobulin- vitamin A and β-lactoglobulin–vitamin D complexes (Masters Thesis). (2005) Raleigh NC: North Carolina State University.

- 16. Eledah, J.I. Calcium chloride-fortified beverages: threshold, consumer acceptability and calcium bioavailability (Masters Thesis). (2005) Raleigh NC: North Carolina State University.

- 17. Iwamoto, J., Takeda, T., Sato, Y. Menatetrenone (vitamin K2) and bone quality in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. (2006) Nutr Rev 64(12): 509-517.

- 18. Iwamoto, J., Yeh, J.K., Takeda, T., et al. Comparative effects of vitamin K and vitamin D supplementation on prevention of osteopenia in calcium-deficient young rats. (2003) Bone 33(4): 557-566.

- 19. Walter, A., Rimbach, G., Most, E., et al. Effect of calcium supplements to maize-soya diet on the bioavailability of minerals and trace elements and the accumulation of heavy metals in growing rats. (2000) J Vet Med 47(6): 367-377.

- 20. Major, G.C., Alarie, F., Doré, J., et al. Supplementation with calcium + vitamin D enhances the beneficial effect of weight loss on plasma lipid and lipoprotein concentration. (2007) Am J Clin Nutr 85(1): 54-59.

- 21. Bronner, F. Mechanisms of intestinal calcium absorption. (2003) J Cell Biochem 88(2): 387-393.

- 22. Heaney, R.P., Barger-Lux, M.J., Dowell, M.S., et al. Calcium absorptive effects of vitamin D and its major metabolites. (1997) J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82(12): 4111-4116.

- 23. Uchikura, C. Bone histoorphometry of the tibia in untreated females Wistar rats. (1999) J East Jpn Orthop Traumatol 11:109-115.

- 24. Boonen, S., Vanderschueren, D., Haentjens, P., et al. Calcium and vitamin D in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis- a clinical update. (2006) J Intern Med 259(6): 539-552.

- 25. Bowen, J., Noakes, M., Clifton, P.M. A high dairy protein, high-calcium diet minimizes bone turnover in overweight adults during weight loss. (2004) J Nutr 134(3): 568-573.

- 26. Murphy, S.C., Whited, L.J, Rosenberry, L.C., et al. Fluid milk vitamin fortification compliance in New York State. (2001) J Dairy Sci 84(12): 2813-2820.

- 27. Gibbs, J.C., Nattiv, A., Barrack, M.T., et al. Low bone density risk is higher in exercising women with multiple triad risk factors. (2014) Med Sci Sports Exerc 46(1): 167–176.