Can We Eat Better Spending Less? Economy and Priorities in the Shopping Basket

Salvador, G1, Manera, M1, Makhmalgi, L2, Soriano, A2, Serra-Majem, L.L3*

Affiliation

- 1Agencia de Salud Pública de Cataluña, Departamento de Salud

- 2Universidad de Barcelona, Campus de la Alimentación de Torribera

- 3Research Institute of Biomedical and Health Sciences, University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria & Nutrition Research Foundation (FIN), Barcelona, Spain

Corresponding Author

Serra-Majem, L.L, Research Institute of Biomedical and Health Sciences, University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria & Nutrition Research Foundation (FIN), Barcelona, Spain; Tel: (+34) 928453475; Fax: (+34) 928451416; E-mail: lluis.serra@ulpgc.es

Citation

Serra-Majem, L.L., et al. Can We Eat Better Spending Less? Economy and Priorities in the Shopping Basket. (2016) J Environ Health Sci 2(4): 1-5.

Copy rights

© 2016 Serra-Majem, L.L. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Food; Budget; Mediterranean diet; Healthy diet

Abstract

A healthy diet is essential to good health. The quality of food depends on food choices which are largely conditioned by the price, availability, culture, preferences, social environment and the level of training responsible for the acquisition and preparation of food, among others.

The increase in food prices, the strong economic crisis suffered in recent years and therefore the high level of unemployment have resulted, among other things, in a reduction in the budget for food in Spanish families. Some studies link the reduction of food expenditure with a lower nutritional quality diet, as well as with weight gain and an increased risk of cardio metabolic complications. The following article proposes a number of strategies to “eat well” (healthy, accessible and sustainable) by changing the shopping cart without increasing the budget, prioritizing the acquisition of plant-based foods and “star foods” (better nutritional value/ price) following the pattern of the traditional Mediterranean diet.

Introduction

Some beliefs suggest that following a healthy diet based on the Mediterranean diet pattern (MD) requires a higher budget on food than families currently spend. That is, to follow the MD is more expensive. Specifically, some studies correlate the budget reduction with a lower consumption of fruits and vegetables and an increased consumption in food with lower nutritional quality (fast -food, pastries, etc.), that may be related to weight gain and an increased risk of cardio metabolic complications in the future[1].

Both the increase in prices experienced in recent years[2] and the effect of the strong economic crisis and the decliningpurchasing power associated with high unemployment[3], have affected, among other factors, in a decrease in the budget allocated to food in Spanish households[4].

How much do we spend on food and what kind of food do we buy?

According to the household survey published by the National Statistics Institute (INE) for 2015[5] most of the average household expenditure was distributed in three main groups:

• Housing, water, electricity and fuels, with an average expenditure of 8,710 €, which represented 31.8 % of total household budget.

• Food and non-alcoholic beverages, which were 4,125 €, 15.1% of the budget.

• Transport, with an average expenditure of 3,158 €, 11.5% of the total.

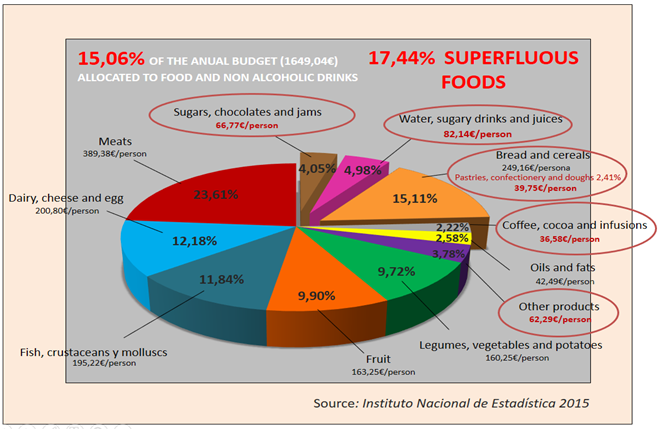

Graphic 1: Distribution of annual per capita expenditure on food and non-alcoholic beverages (INE, 2015).

Going into more detail in spending on food and beverages, 15.1% of total household budget represents about 1,649 € person/year (about 31.1 € person/week). Interestingly, 17.4 % (€ 287.53 person / year) of the investment is spent in food and drinks included in the food group of “occasional consumption”. That is, in foods that are concentrated in the top of the pyramid: soft drinks and juices, cocoa, pastries, cakes and biscuits, sugar, chocolates and jams, sauces, etc. (See “Healthy Eating Pyramids” from NAOS, SENC, ASPCAT)[6-8]

These figures do not include the budget for 2015 to alcoholic beverages, accounted for 71.44 € person/year[5]..

Strategies

1. Modify the distribution of the budget for the shopping cart.

Based on this information and on the recommendations of scientific societies on the desirability of reducing the consumption of foods of low nutritional value (high energy intake of saturated and trans fats, sugars and/or salt), individuals can consider a good strategy to improve the quality of the menus, without increasing the budget in the shopping cart. Invest 17.4 % for superfluous foods in other food groups, mainly low- processed plant-based, located at the base of the healthy eating pyramid (food considered for daily consumption).

2. Increase the proportion of plant-based minimally processed foods.

Currently, institutions and health organizations dedicated to promoting health through food, agree on the overall characteristics that dietary patterns should have, in order to promote the protection of health and prevent disorders caused by excesses, deficits and imbalances in the diet. In general, the healthiest food models are characterized by mass consumption of plant foods (in our environment: fruits, vegetables, legumes, bread, rice, pasta, nuts, olive oil), which are accompanied by small portions of fish, lean meats, eggs and dairy, and water to drink.

The World Health Organization (WHO)[9] recommends a varied diet based mainly on plant foods instead of animal, including especially bread, pasta and rice (whole grains) several times a day, as well as fruits and vegetables in abundant quantities daily. The same recommendations are done by American reference entities, such as the Public Health School at Harvard University[10] stating that the basis of a healthy diet are plantbased foods. The new Dietary Guidelines for Americans[11] state that a diet rich in plant foods, low in calories and in animal foods, promotes health and is associated with a lower environmental impact. In our environment, the Spanish Agency for Consumer Affairs, Food Security and Nutrition (AECOSAN), in the framework of the NAOS Strategy[12] considers as daily foods that have to form the basis of the diet: fruits and vegetables, grains, dairy products, bread and olive oil. According to the overall 2015 food budget, the meat group accounts for 23.6 %, 398.4€ per year, of which 160.9€ destine to charcuterie and 42.8€ to prepared meat. Only by halving this we would have the amount of 100€ a year to increase the purchase, for example, of legumes, high in protein and fiber and with a very low economic and environmental cost.

Although there are multiple eating patterns that meet the criteria of healthy eating, in our territory highlights undoubtedly the Mediterranean Diet. The health claims attributed to this diet are based on the finding that the incidence of cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome[13], Type 2 diabetes[14], cancer[15] and even some neurodegenerative diseases[16] is lower in populations who follow this dietary pattern. In addition, studies point to a possible role of the Mediterranean diet in the prevention of overweight and obesity[17]. Moreover, overall plant foods with minimal process are usually cheaper than those of animal origin.

3. Prioritize “star foods” of the Mediterranean Diet.

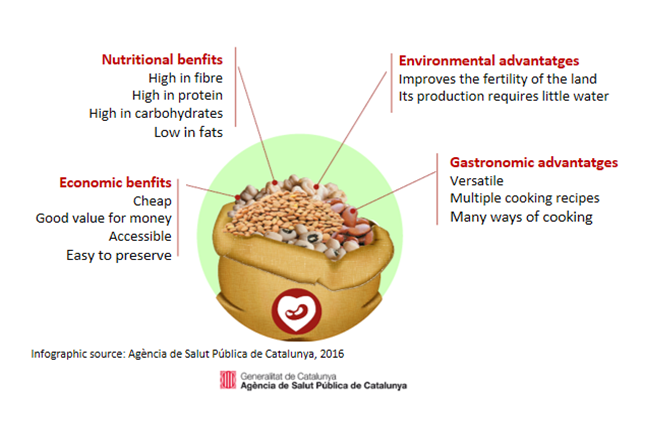

The Mediterranean diet, in addition to their nutritional and health protection qualities, is a cultural, historical, social, territorial and environmental heritage that has been passed from generation to generation for centuries and is closely linked to the lifestyles of the Mediterranean people. The traditional Mediterranean diet has less impact on water consumption, although to a lesser extent, on energy consumption than current Mediterranean and Western-globalized diets. The latter, are more based more on meat, processed meat consumption and dairy products consumption. Within the traditional Mediterranean diet pattern, we understand as “star foods” those which present an excellent nutritional quality / price. Star foods are: seasonal, local fruits and vegetables, some nuts such as hazelnuts, in the group of animal foods, eggs, among others. But the food whose nutritional quality / price ratio is higher is legumes. Legumes are a key element in the Mediterranean Diet[18]. For this reason, legumes are chosen to highlight all its properties. At the same time, its consumption is very low among the population.

Legumes: Mediterranean countries have the highest consumption of plant-based foods in Europe, with Spain leading the consumption in the region of southern Europe .Europe. However, in recent decades the trend in consumption of legumes has declined dramatically[19]. Currently, the consumption of legumes in Spain is around 3.1 Kg person / year, representing a per capita annual expenditure of € 5.15[4]. This represents a weekly consumption of legumes of approximately 100 g, equivalent to half of the weekly intake recommendations (the recommendation is 2 to 4 servings per week,, considering 1 serving between 60 to 80 g)[20-23].

With regard to the nutritional composition, legumes include contain both the beneficial nutrients containing (fiber, vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, proteins, carbohydrates), and by the failure to provide lack (or to provide containin very small amounts) not recommended of those nutrients not recommended (salt, saturated fat and sugars). In the healthy eating pyramid, legumes are represented both in the base, in the group of starchy foods (along with bread, pasta, rice and potatoes) and in the food group of weekly consumption (together with lean meat, fish and eggs), for its high content of carbohydrates and protein. They can be ideal substitutes for meat, which, in our environment, its consumption becomes excessive and expensive. In addition high animal protein intake, especially that from processed red meat, is positively associated with mortality[24]. For example, 100 grams of dried lentils contain 24 grams of protein, while 100 grams of beef steak or chicken breast provide 20 grams. Although legumes are poor in the essential amino acid methionine, this deficiency does not involve any problem in the context of a balanced diet, as it is offset by other foods containing methionine in greater proportion. For this reason, often, legume preparations can be excellent unique dishes or main courses (accompanied by salads, soups, fresh fruit, etc.), and are also the most economical source of protein that can be found.

The nutritional composition of legumes explains largely the many health benefits of consumption. Its high fiber content provides satiety and facilitates intestinal transit. Studies conclude that the regular intake of legumes lowers cholesterol, triglycerides, and some cancers and promotes cardiovascular health[25,26]. Pulses are very rich in nutrients important for a healthy diet and relevant to chronic disease issues of global significance including obesity, diabetes, heart disease and cancer. The intake of legumes is linked with lower risk for diabetes, due to its glucose- and lipid-lowering action possessed. Consumption of legumes are also beneficial in decreasing the risk factors for cardiovascular and renal disease[27]. Some studies also report benefit of increased vegetable protein consumption in relation to heart disease. Furthermore, there is existing research related to pulse consumption, satiety and weight management, and also related to the prevention of certain types of cancer[28].

In some cases, the consumption of pulses can cause flatulence because they contain indigestible fiber which reaches the colon, are fermented by bacteria, and generate gases and compounds beneficial to health.

In the dining area, legumes offer a wide range of culinary possibilities. Its versatility of colors, textures and flavors allows them to be part of winter recipes, such as classic dishes, stews and soups, and refreshing recipes such as salads, cold soups and pates[22,23].

What are the economic advantages of consuming legumes? Increased consumption of vegetables and reduce consumption of foods of animal origin may represent a significant savings on the food budget. Legumes, besides being nutritionally a very complete food, are also very cheap (one kilo of raw legume: 1.5 - 3.5 €, a kilogram of cooked canned legume: 1 - 3 €, and 1 kilo of cooked legume market : 4 - 5 €). This relationship between nutritional quality and price is what makes legumes a “star food.”

Legumes, for all its characteristics, nutritional, environmental, gastronomic, and affordability are the subject of numerous campaigns to promote health where the increase in their consumption is promoted. The Food and Agriculture Organization, FAO, has proclaimed 2016 as the International Year of Legumes[22].

However, is it clear that at a global level the consumption of fruit and vegetables is low worldwide, particularly in low income countries, and this is associated with low affordability? Policies worldwide should prioritize to enhance the availability and affordability of fruits and vegetables[29].

Table 1: Comparison of nutritional composition and price of vegetables and meat. Salvador G.

| FOOD | Nutritional composition for edible portion | Price per serving (€) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | Proteins (g) | Carbohydrates (g) | Fats (g) | Fibre (g) | ||||

| Saturated | Unsaturated | |||||||

| Raw meat (150 g) | Chicken breast | 208,7 | 25,0 | 0 | 3,3 | 7,7 | 0 | 0,92 |

| Loin of pork | 342,2 | 20,7 | 0 | 9,3 | 16,6 | 0 | 0,60 | |

| Veal breast | 164,2 | 25,9 | 0 | 2,7 | 3,3 | 0 | 1,10 | |

| Raw legumes (80 g) | Chickpeas | 298 | 15,5 | 44,0 | Traces | 4,2 | 12,0 | 0,12 |

| Lentils | 280 | 19,4 | 43,2 | 0,3 | 0,8 | 9,4 | 0,12 | |

| Beans | 279 | 15,2 | 42,0 | 1,2 | 20,3 | 0,12 | ||

Figure 1: Infographic: Legumes, a super food. Public Health Agency of Catalonia, 2016.

4. Tools to promote healthy and affordable food

Have information, skills, abilities and means to properly select foods and preparations that will shape our daily diet is essential both to improve the nutritional quality of menus and to adjust the budget. Economic insecurity is not the only cause of malnutrition. The lack of financial resources and a lack of skills and low knowledge of techniques for selection, handling and preparation of food is the ideal combination for a low quality dietary pattern.

Provide information and tools to improve the skills of buying and preparing food must also be public health priorities. (See document “Eating healthy with less money. 10 tips to get more out of your Euros ASPCAT, 2014”)[30].

Conclusion

Although in recent years the trend in relation to the budget for food in Spanish households has been downward, and that there is some evidence that lowering the investment the quality of the diet decreases, it is possible to follow a healthy diet in our environment without increasing the total budget. This requires promoting some measures, as described in this article, which focus on: 1-to change rates of purchase, reducing occasional consumption and low nutritional quality food purchases, 2-to increase the acquisition of plant-based food, following the Mediterranean diet pattern, 3-to give priority to foods from the Mediterranean diet with better nutritional quality/price, such as legumes, 4-to promote and facilitate training tools to plan the purchase and preparation of healthy menus. All of them should be integrated and promoted in policies of public health and community nutrition strategies.

References

- 1. Schröder, H., Serra-Majem, L., Subirana, I., et al. Association of increased monetary cost of dietary intake, diet quality and weight management in Spanish adults. (2016) Br J Nutr 115(5): 817-822.

- 2. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Evolución de la tasa de paro en España. (2016)

- 3. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta de presupuestos familiares. Evolución del IPC general e IPC de los alimentos y bebidas no alcohólicas. (2016)

- 4. Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente. Gobierno de España. Informe del consumo de alimentación en España. (2015).

- 5. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta de presupuestos familiares. Cantidades físicas consumidas y gasto.

- 6. Agencia Española de Consumo, Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición. NAOS. Pirámide de la Alimentación Saludable.

- 7. Sociedad Española de Nutrición Comunitaria, SENC. Pirámide de la Alimentación Saludable.

- 8. Agencia de Salut Pública de Cataluña. PAAS. Pirámide de la Alimentación Saludable.

- 9. World Health Organization. A Healthy Lifestyle. WHO Europe.

- 10. The Nutrition Source: Healthy Eating Plate & Healthy Eating Pyramid. Havard T.H.Chan.

- 11. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotions. Advisory report. (2015) DPHP

- 12. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales E Igualdad. Pirámide NAOS (2015).

- 13. Becerra-Tomás, N., Babio, N., Martínez-González, M.Á., et al. Replacing red meat and processed red meat for white meat, fish, legumes or eggs is associated with lower risk of incidence of metabolic syndrome. (2016) Clin Nutr S0261-5614(16)30005-X.

- 14. Salas-Salvadó, J., Guasch-Ferré, M., Lee, C.H., et al. Protective Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on Type 2 Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome. (2016) J Nutr

- 15. Verberne, L., Bach-Faig, A., Buckland, G., et al. Association between the Mediterranean diet and cancer risk: a review of observational studies. (2010) Nutr Cancer 62(7): 860-870.

- 16. Valls-Pedret, C., Lamuela-Raventós, R.M., Medina-Remón, A., et al. Polyphenol-rich foods in the Mediterranean diet are associated with better cognitive function in elderly subjects at high cardiovascular risk. (2012) J Alzheimers Dis 29(4):773-782.

- 17. Obesidad. Recomendaciones nutricionales basadas en la evidencia para la prevención y el tratamiento del sobrepeso y la obesidad en adultos (Consenso FESNAD-SEEDO). (2011) Revista Espanola de 10.

- 18. Pirámide de la dieta mediterránea: un estilo de vida actual. (2010).

- 19. Food Balances. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Statistic Division. (2015) FAOSTAT.

- 20. Sociedad Española de Nutrición Comunitaria (SENC), Sociedad Española de Medicina de Familia y Comunitaria (semFYC). Consejos para una alimentación saludable. Madrid: SENC, sem FYC; (2007).

- 21. Agencia de Salut Pública de Cataluña. Recomendaciones de alimentación saludable.

- 22. Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura, FAO. (2016) Año internacional de las legumbres.

- 23. Agencia de Salut Pública de Cataluña. Monogràfic sobre els llegums.

- 24. Song, M., Fung, T.T., Hu, F.B., et al. Association of Animal and Plant Protein Intake With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. (2016) JAMA Intern Med 176(10): 1453-1463.

- 25. Bazzano, L.A., Thompson, A.M., Tees, M.T., et al. Non-soy legume consumption lowers cholesterol levels: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. (2011) Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 21(2): 94-103.

- 26. Ha, V., Sievenpiper, J.L., de Souza, R.J., et al. Effect of dietary pulse intake on established therapeutic lipid targets for cardiovascular risk reduction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

- 27. Singhal, P., Kaushik, G., Mathur, P. Antidiabetic potential of commonly consumed legumes: A Review. (2014) Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 54(5): 655-672.

- 28. Curran, J. The nutritional value and health benefits of pulses in relation to obesity, diabetes, heart disease and cancer. (2012) Br J Nutr 108(Suppl 1): S1-S2.

- 29. Miller, V., Yusuf, S., Chow, C.K., et al. Availability, affordability, and consumption of fruits and vegetables in 18 countries across income levels: findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. (2016) Lancet Glob Health 4(10): e695-e703.

- 30. Agencia de Salut Pública de Catalunya. Comer sano con menos dinero.