Casr-Inhibitor Treatment Prevents Hypertension Induced Cardiac Fibrosis and Remodeling

Affiliation

Department of Cardiology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin150001, and Heilongjiang Province, China

Corresponding Author

Department of Cardiology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, No.23, You Zheng Street, Nan Gang District, Harbin 150001, Heilongjiang Province, China, Tel: 86 451 85555063; E-mail: yinxinhua5063@163.com

Citation

Yin, X., et al. Casr-Inhibitor Treatment Prevents Hypertension Induced Cardiac Fibrosis and Remodeling. (2018) J Heart Cardiol 4(1): 6- 10.

Copy rights

© 2018 Yin, X. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Calcium sensing receptor (CaSR); Hypertension; Cardiac fibrosis; Spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs); Cardiac remodeling

Abstract

Introduction: Myocardial fibrosis induced by hypertension results in cardiac remodeling and dysfunction. It has been demonstrated that calcium sensing receptor (CaSR) activation is involved in calcium overload during cardiac fibrosis. This study investigated the role of Calhex231, a CaSR inhibitor in preventing cardiac fibrosis in a model of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR).

Methods and results: Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats were used in this study as normotensive controls. Cardiac function, hypertrophy index and blood pressure were determined at the end of the study. The results showed that Calhex231 treatment reduced the blood pressure, cardiac fibrosis and extracellular matrix (ECM) secretion in SHRs. Moreover, western blot results showed that the elevated expression levels of CaSR, matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 (MMP-2 and -9) induced by hypertension were suppressed by Calhex231 administration.

Conclusions: We found inhibition of CaSR through decreasing the deposition of ECM can treat cardiac remodeling.

Introduction

Myocardial fibrosis, which is characterized by accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) and deposition of excessive collagen, develops to left ventricular (LV) diastolic dysfunction, myocardial remodeling and heart failure[1-3]. Studies have shown that the cardiomyocytes replaced by cardiac fibroblasts and pressure overload leading to ECM deposition are the two reasons of fibrosis[4]. Since the mechanism of fibrosis is complex, seeking protective effect of novel treatment is urgent.

Calcium sensing receptor (CaSR), is a Class C G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) involved in Ca2+ homeostasis[6,7]. Brown et al[8] have first discovered its expression in the parathyroid, and then its existence was found in different tissues[6]. Increased extracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]0) binds to CaSR, activating phospholipase C (PLC) signalling pathway, leading to accumulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphophate (IP3)[6]. A previous work demonstrated that CaSR promoted cardiac fibroblast proliferation via Ca2+ signaling involved in cardiac fibrosis through the PLC-IP3 pathway[9]. However, no evidence had shown that CaSR was involved in hypertensive cardiac remodeling at present. In this study, we aimed to explore the effects of Calhex231, the inhibitor of CaSR, on myocardial fibrosis by modulating ECM secretion in vivo.

Methods

Materials and reagents: 20 weeks old male Spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) and Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats were obtained from Vital River Laboratories (Beijing, China).All animal experimental procedures were complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of National Institutes of Health. Calhex231 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibody against CaSR was purchased from Alpha Diagnostic International Inc. (San Antonio, Texas, USA).Antibodies against MMP-2, MMP-9, α-SMA, TIMP-2and β-actin were from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA, USA). All secondary antibodies G were purchased from Rockland (PA, USA). Poly vinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes were acquired from what man (now part of GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Buckinghamshire, (UK).

Animal study: Twenty male spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) and ten age-matched male Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats were randomly divided into three groups: (1) WKY(n = 10), the 20-week-old Wistar-Kyoto rat group were intraperitoneal (i.p) injected with saline (2 mL/kg/day) for 4 weeks; (2) SHR (n = 10), the 20-week-old SHRs group were i.p. Injected with saline (2 mL/kg/day) for 4 weeks, and (3) SHR plus Calhex231 (n = 10,SHR+Calhex231), the 20-week-old SHRs were received a daily i.p injection of Calhex231 (10 μmol/kg) which was administered in saline for 4 weeks.

All animals were housed in separate cages under standard conditions with free access to food and water. The blood pressure of the rats was carried out by the caudal artery using the RBP-1 method in each rat once a week. Four weeks later, the rats were anesthetized before echocardiograms, and then the whole hearts were quickly removed and storaged at -80°C until western blot analyses.

Echocardiograph evaluation: Cardiac functions were obtained using a Vivid 7 Dimension echocardiography machine (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA). The rats were anaesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate at 0.3 ml/100 g body weight i.p and adjusted to the left lateral decubitus position self-breathing. The images and data were recorded for analysis.

Histological analysis: The hearts were fixed in 4% para formaldehyde at room temperature for 24 h and then embedded in paraffin, sliced into 4-μm thick sections, and stained with Masson’s trichrome reagent. Fibrosis tissue which was stained blue, quantified by Image-Pro Plus v4.0software.

Western-blot analysis of proteins in left ventricular tissues

Protein concentrations were determined using an enhanced BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, Nantong, China). The equal amounts of protein were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Then the samples were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore) and blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk dissolved in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were incubated at 4°C overnight with the primary antibodies anti- CaSR (1:500), anti-MMP-2 (1:1000), anti-MMP-5 (1:1000), anti-α-SMA (1:500), anti-TIMP-2(1:500), and anti-β-actin (1:1000). After washing with TBST, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies fluorescence-conjugated goat anti-rabbit oranti-mouse IgGs (1:5,000; Rockland) in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. Bands were scanned by an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR) and Odyssey v3.0 software. The results were analyzed with Image J software, and β-actin was used as an internal control for the normalized assay.

Statistical analysis: The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Graph Pad Prism 5.0 software was used for the data analyses. We use done-way ANOVA to compare more than two groups. For all analyses, values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Each experiment was repeated a minimum of three times.

Results

Effects of CaSR on myocardial function and cardiac fibrosisin spontaneously hypertensive rats

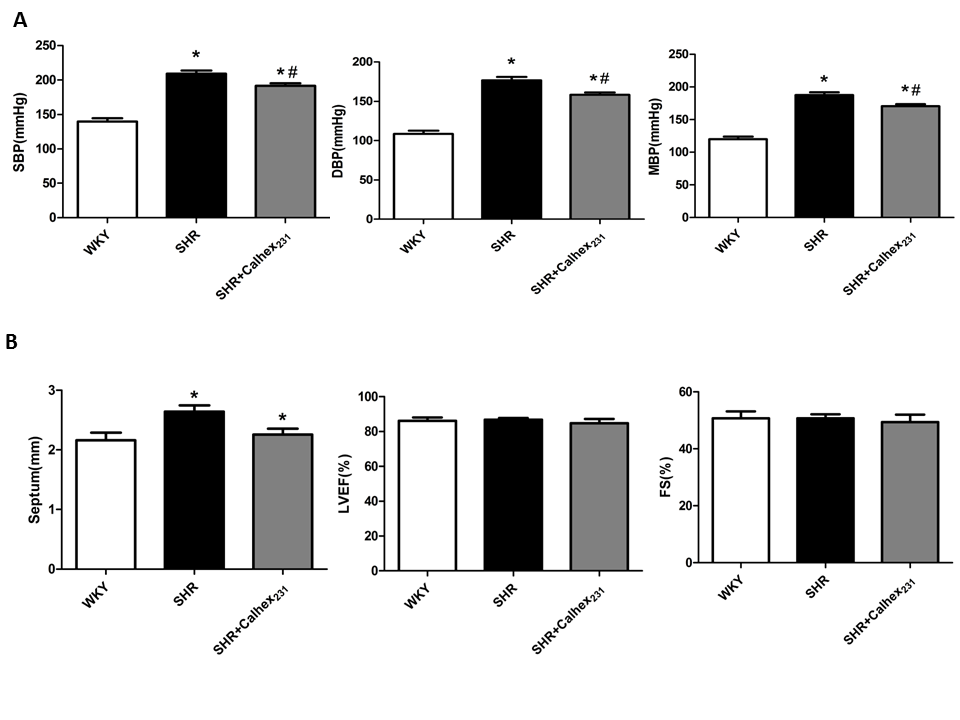

To investigate the effect of CaSR on myocardial fibrosis in the hypertensive heart, we used a model of SHRs to study the development of cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac remodelling. In the SHR and SHR + Calhex231 groups, systolic blood pressure , diastolic blood pressure and mean arterial pressure were significantly higher compared to the WKY group (P < 0.05); however, the elevated blood pressure was reduced by the treatment of Calhex231 compared with that in the SHRs group (P < 0.05, Figure.1A).

Figure 1: Effect of Calhex231 on the blood pressure and cardiac function in SHRs. WKY: normo tensive age-matched control rats, SHR: 24 week-old SHRs, SHR + Calhex231: 24 week-old SHR treated with Caldex231 for 4 weeks. (A) Calhex231 treatment influences the blood pressure in SHRs.SBP: systolic blood pressure, DBP: diastolic and blood pressure, MBP: mean arterial blood pressure. Values are presented as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 versus the WKY group. #P < 0.05 versus the SHR group. n = 7 per group. (B) Effect of Calhex231 on cardiac function in SHRs heart. The data are detected by echocardiography. Septum: thickness of septum, EF: ejection fraction, FS: fractional shortening. Values are presented as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 versus the WKY group. n = 7 per group.

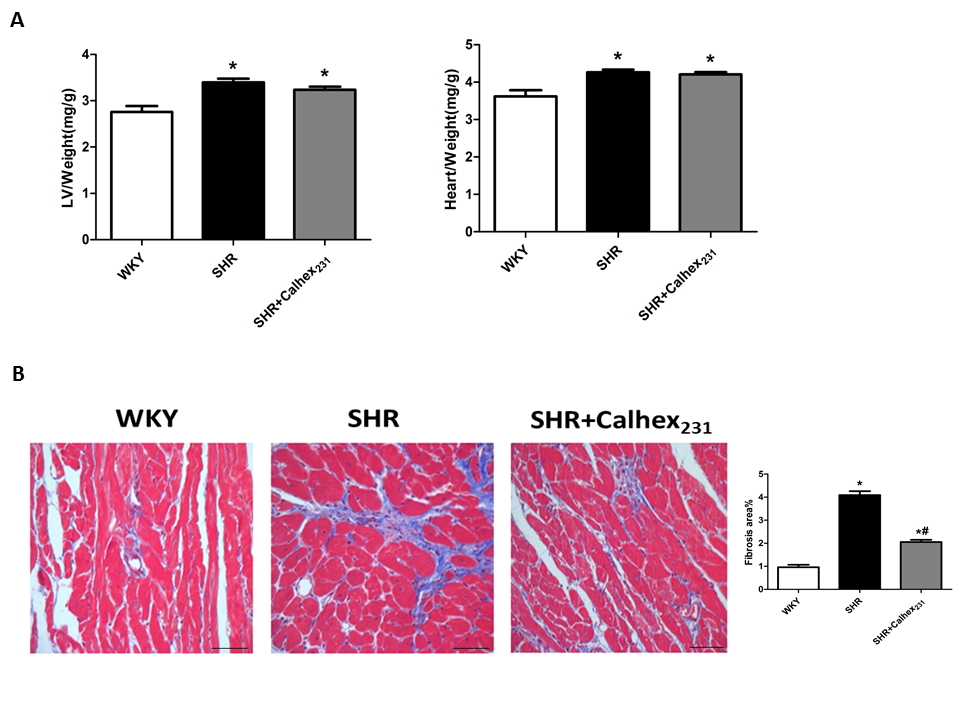

Echocardiography results showed myocardial function. Compared with the WKY group, the thickness of the septum was increased in the SHR group (P < 0.05, Figure.1B). As shown in Figure.1, no differences were observed in LV systolic functions (EF and FS) between the three groups at 24 weeks of age. The degree of hypertrophy were determined by HW/BW (heart weight to body weight ratio) and LVW/BW (left ventricular weight to body weight ratio).Our results showed that SHR shad an increased HW/BW ratio compared to the control WKY rats (all P < 0.05, Figure.2A). Similar result was observed in LVW/BW ratio (P < 0.05, Figure.2A) .These results show the presence of hypertrophy but not congestive heart failure in the SHR group.

Masson’s staining was to detect the collagen deposition in the cardiac tissue. SHRs presented a remarkable increase in the muscle fibres compared with the WKY group (P < 0.05). Moreover, Calhex231 treatment ameliorated cardiac fibrosis induced by hypertension compared with the SHR group (P < 0.05, Figure.2B).

Figure 2: Effect of Calhex231 on gravimetric parameters and cardiac fibrosis of SHRs. (A) LVW: weight of left ventricle, HW: heart weight, BW: body weight. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 versus the WKY group. n = 7 per group. (B) Calhex231 treatment decreased the deposition of interstitial collagen in SHRs heart. Sections of cardiac tissue were observed by Masson staining, magnification: 400, Scale bar: 25 µm. The bar graph presents statistical analysis of myocardial fibrotic area. Values are represented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus the WKY group; #P < 0.05 versus the SHR group. n = 6 per group.

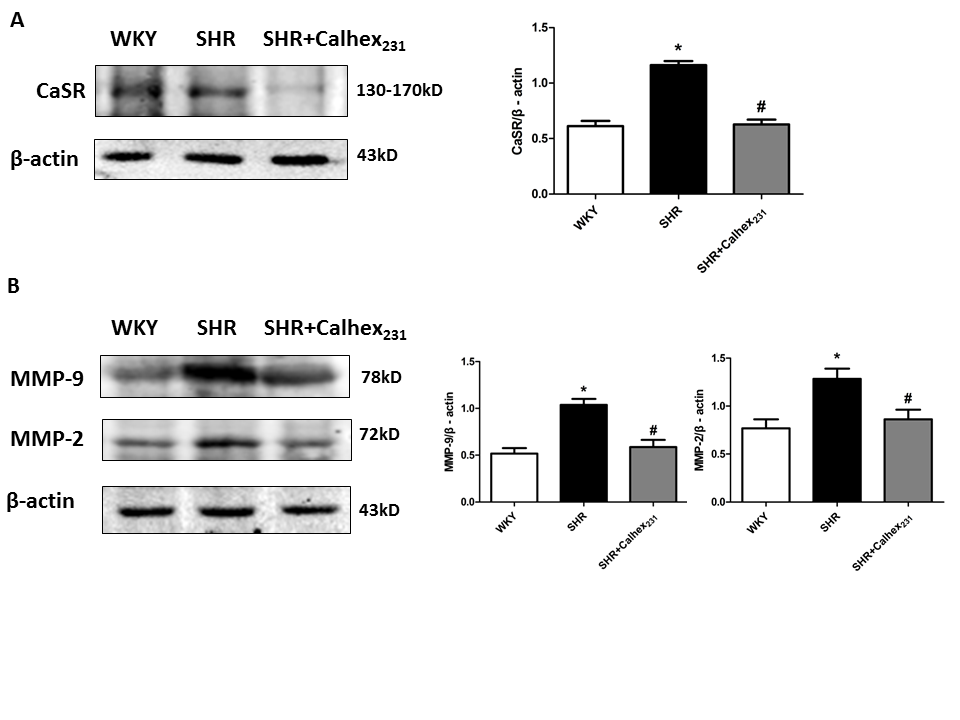

Expression of CaSR protein

Western blot analysis showed that the expression of CaSR was increased in the SHR group, compared to the WKY group (Figure.3A). Moreover, the increase was reduced after Calhex231 treatment (P < 0.05, Figure.3A).

Figure 3: Protein expression of CaSR and MMPs in rat heart tissues was determined by western blot analysis. (A) Western blots analysis and summarized data of CaSR. Protein levels were normalized to β-actin. Values represent mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 versus the WKY group. #P < 0.05 versus the SHR group. n = 6 per group. (B) Western blots analysis and summarized data of MMP-9 and MMP-2. Protein levels were normalized to β- actin. Values represent mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 versus the WKY group. #P < 0.05 versus the SHR group. n = 6 per group.

Western blot analysis of indicator of cardiac fibrosis

We performed Western blot to explore the protein levels of indicators of myocardial fibrosis for the three groups. The expression of MMP-9 and MMP-2 were increased in the SHR group compared to the WKY group (P < 0.05, Figure.3B). But Calhex231 treatment decreased the protein levels of these proteins (P < 0.05, Figure.3B).

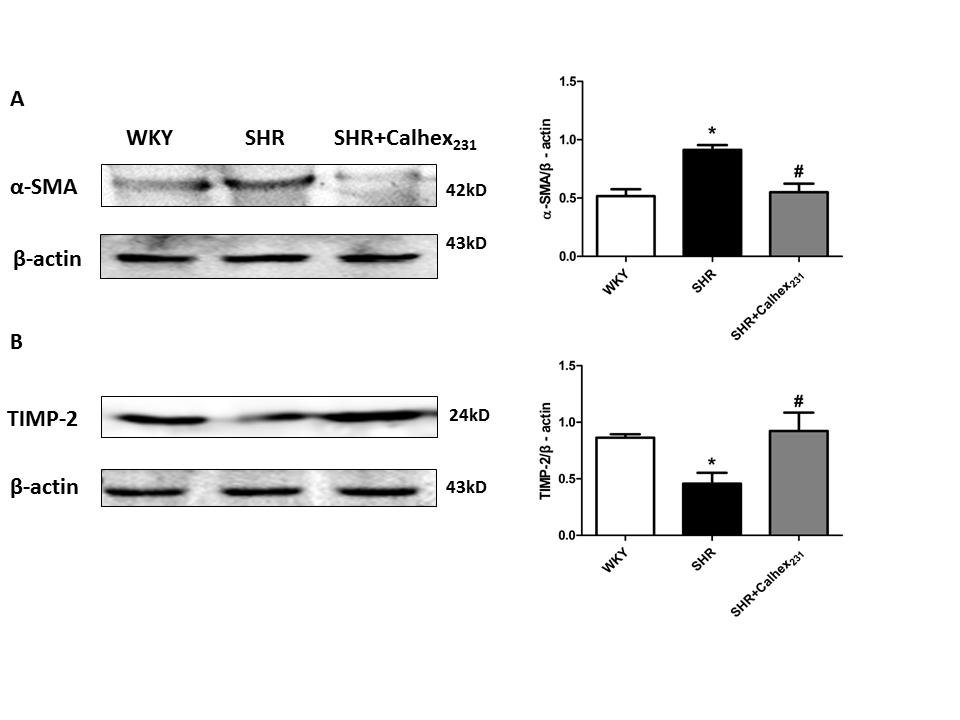

The expression of α-SMA (alpha-smooth muscle actin) wasincreased in the SHR groupcompared to the WKY group and Calhex231 treatment decreased the protein level of α-SMA (P < 0.05, Figure.4A). Our result showed that TIMP-2 expression was significantly decreased in the SHR group compared to the WKY group, but was elevated in SHR + Calhex231-treated group (P < 0.05, Figure. 4B).

Figure 4: The effect of Calhex231 on extracellular matrix production in SHRs. (A) Western blot analysis and summarized data of α-SMA. Protein levels were normalized to β-actin. Values represent mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 versus the WKY group. #P < 0.05 versus the SHR group. n = 6 per group. (B) Western blots analysis and summarized data of TIMP-2. Protein levels were normalized to β-actin. Values represent mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 versus the WKY group. #P < 0.05 versus the SHR group. n = 6 per group.

Discussion

Calcium sensing receptor (CaSR) distributes primarily on the parathyroid glands, regulating the release of the calcium-retaining hormone, parathyroid hormone (PTH)[6]. The significant role of CaSR is regulating intracellular calcium homeostasis through Ca2+ signaling pathways[10]. Studies have observed the existence of CaSR in cardiovascular system, like neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs)[11], rat cardiac fibroblasts[9] and vascular smooth muscle[12]. Moreover, CaSR plays an important role in many diseases, such as hypoxia/reoxygenation[13], cardiomyocyte apoptosis[11], myocardial infarction[14], cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure[15].

Previous studies have also reported that the activation of CaSR induces the release of PTH which lowers blood pressure[7,8,16]. However, Schluter et al noted that inhibition of CaSR maybe not reduce the release of PTH[17]. And Sutherland found that low level of [Ca2+]o could stimulate the secretion of parathyroid hypertensive factor (PHF) in parathyroid gland organ cultures[18]. There are many factors involving the regulating the blood pressure, such as effect of the Ca2+ or CaSR on vascular tone, secretion of hormonal (like renin, PTH and so on) and the drug’s pharmacological effects[19]. So, the mechanism of CaSR in the regulating blood pressure needs further investigation in the following study.

In human cardiac fibroblasts, people found that calcium homeostasis is regulated by IP3 receptor (IP3R)[20]. A study revealed that extracellular calcium activated of CaSR increasing intracellular Ca2+ [Ca2+]i levels through the PLC-IP3 pathway and promoted proliferation and migration of neonatal cardiac fibroblast and ECM remodeling[9]. Our study showed that Calhex231 was able to suppress myocardial fibrosis in SHRs. This result demonstrates that CaSR is involved in the hypertension induced cardiac remodeling. So we hypothesizes that activation of the CaSR promotes cardiac fibrosis through the PLC-IP3 pathway.

Because of the longtime increased workload, the heart progresses to hypertrophy, fibroblast proliferation and ECM secretion[21]. And the fibroblasts cooperate with the collagen network influencing myocardial relaxation and contractility[22]. In our present study, Masson staining results showed an obvious increase in collagen deposition in the SHRs group, whereas Calhex231 diminished collagen area of myocardial fibrosis. The expression of MMP-2, MMP -9 and α-SMA were elevated in SHRs group indicating of fibrotic tissue remodeling, and treatment with Calhex231 decreased the expression levels of these proteins. And Calhex231 unregulated the decreased expression of TIMP-2 in SHRs. Moreover, MMPs have a significant role in the ECM remodeling. During repairing of the damage, MMPs destroy the network of the collagen and promote inflammatory cell gathering, leading to releasing of cytokines. Then it results in fibroblast proliferation and excessive deposition of ECM[23]. Additionally, studies showed that many factors, including inflammatory cytokines, hormones and mechanical stretch can affect proliferation, migration and gene expression of fibroblasts[24,25]. Our data prove that CaSR can be involved in the mechanism of cardiac remodeling mentioned above.

Conclusion

The study demonstrated that CaSR is involved in cardiac fibrosis induced by hypertension. For the first time, we provide experimental evidence for treating cardiac remodeling by inhibition of CaSR through decreasing the deposition of ECM. The present study could provide novel approaches for the preventing cardiac fibrosis.

Acknowledgments: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570437, 81370319).

References

- 1. Broberg, C.S., Burchill, L.J. Myocardial factor revisited: The importance of myocardial fibrosis in adults with congenital heart disease. (2015) Int J Cardiol 189: 204-210.

- 2. Donekal, S., Venkatesh, B.A., Liu, Y.C., et al. Interstitial fibrosis, left ventricular remodeling and myocardial mechanical behavior in a population-based multiethnic cohort: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) study. (2014) Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 7(2): 292-302.

- 3. Lorell, B.H., Carabello, B.A. Left ventricular hypertrophy: pathogenesis, detection, and prognosis. (2000) Circulation 102(4): 470-479.

- 4. Weber, K.T. Cardiac interstitium in health and disease: the fibrillar collagen network. (1989) J Am Coll Cardiol 13(7): 1637-1652.

- 5. Berk, B.C., Fujiwara, K., Lehoux, S. ECM remodeling in hypertensive heart disease. (2007) J Clin Invest 117(3): 568-575.

- 6. Brown, E.M., MacLeod, R.J. Extracellular calcium sensing and extracellular calcium signalling. (2001) Physiol Rev 81(1): 239-9.

- 7. Wang, R., Xu, C., Zhao W., et al. Calcium and polyamine regulated calcium sensing receptors in cardiac tissues. (2003) Eur J Biochem 270(12): 2680-2688.

- 8. Brown, E.M., Gamba, G., Riccardi, D., et al. Cloning and characterization of an extracellular Ca (2+)-sensing receptor from bovine parathyroid. (1993) Nature 366(6455): 575-580.

- 9. Zhang, X., Zhang, T., Wu, J. et al. Calcium sensing receptor promotes cardiac fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix secretion. (2014) Cell Physiol Biochem 33(3): 557-568.

- 10. Tu, C.L., Chang, W., Bikle, D.D. The role of the calcium sensing receptor in regulating intracellular calcium handling in human epidermal keratinocytes. (2007) J Invest Dermatol 127(5): 1074-1083.

- 11. Sun, Y.H., Liu, M.N., Li, H., et al. Calcium-sensing receptor induces rat neonatal ventricular cardiomyocyte apoptosis. (2006) Biochem Biophys Res Commun 350(4): 942-948.

- 12. Smajilovic, S., Hansen, J.L., Christoffersen, T.E., et al. Extracellular calcium sensing in rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells. (2006) Biochem Biophys Res Commun 348(4): 1215-1223.

- 13. Lu, F.H., Tian, Z., Zhang, W.H., et al. Calcium-sensing receptors regulate cardiomyocyte Ca2+ signaling via the sarcoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrion interface during hypoxia/reoxygenation. (2010) J Biomed Sci 17: 50.

- 14. Liu, W.X., Zhang, X., Zhao, M., et al. Activation in M1 but not M2 Macrophages Contributes to Cardiac Remodeling after Myocardial Infarction in Rats: a Critical Role of the Calcium Sensing Receptor/NLRP3 inflammasome. (2015) Cell Physiol Biochem 35(6): 2483-2500.

- 15. Lu, F.H., Fu, S.B., Leng, X., et al. Role of the Calcium-Sensing Receptor in Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis via the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum and Mitochondrial Death Pathway in Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure. (2013) Cell Physiol Biochem 31(4-5): 728-743.

- 16. Conigrave, A.D., Quinn, S.J., Brown, E.M. L-Amino acid sensing by the extracellular Ca2+ -sensing receptor. (2000) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97(9): 4814-4819.

- 17. Schluter, K.D., Piper, H.M. Cardiovascular actions of parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide. (1998) Cardiovasc Res 37(1): 34-41.

- 18. Sutherland, S.K., Benishin, C.G. Regulation of parathyroid hypertensive factor secretion by Ca2+ in spontaneously hypertensive rat parathyroid cells. (2004) Am J Hypertens 17(3): 266-272.

- 19. Smajilovic, S., Yano, S., Jabbari, R., et al. The calcium-sensing receptor and calcimimetics in blood pressure modulation. (2011) Br J Pharmacol 164(3): 884-893.

- 20. Li, G.R., Sun, H.Y., Chen, J.B., et al. Characterization of multiple ion channels in cultured human cardiac fibroblasts. (2009) PLos One 4(10): 7307.

- 21. Petrov, V.V., Fagard, R.H., Lijnen, P.J. Stimulation of collagen production by transforming growth factor-beta1 during differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. (2002) Hypertension 39(2): 258-263.

- 22. Troy, A. B., Wayne, C., Wayne, G., et al. Cardiac fibroblasts: friend or foe? (2006) Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291(3): 1015-1026.

- 23. Creemers, E.E., Cleutjens, J.P., Smits, J.F., et al. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition after myocardial infarction: a new approach to prevent heart failure? (2001) Circ Res 89(3): 201-210.

- 24. Burgess, M.L., Terracio, L., Hirozane, T., et al. Differential integrin expression by cardiac fibroblasts from hypertensive and exercise- trained rat hearts. (2002) Cardiovasc Pathol 11(2): 78-87.

- 25. Diaz-Araya, G., Borg, T.K., Lavandero, S., et al. IGF-1 modulation of rat cardiac fibroblast behaviour and gene expression is age-dependent. (2003) Cell Commun Adhes 10(3): 155-165.