Changes in Stress Responses in Juvenile Rockfish Sebastes Schlegelii Exposed to Dietary Lead (Pb) and Ascorbic Acid

Jun-Hwan Kim1, Ju-Chan Kang2*

Affiliation

- 1West Sea Fisheries Research Institute, National Institute of Fisheries Science, Incheon 22383, Korea

- 2Department of Aquatic Life Medicine, Pukyong National University, Busan 48513, Korea

Corresponding Author

Ju-Chan Kang, Department of Aquatic Life Medicine, Pukyong National University, Busan 48513, Korea, Tel: +82 51 629 5944; Fax: +82 51 629 5938; E-mail: jckang@pknu.ac.kr

Citation

Kang, J.C., et al. Changes in Stress Responses in Juvenile Rockfish Sebastes Schlegelii Exposed to Dietary Lead (Pb) and Ascorbic Acid. (2017) J Marine Biol Aquacult 3(1): 1- 5.

Copy rights

© 2017 Kang, J.C. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Sebastes schlegelii; Pb; Ascorbic acids; Stress indicators

Abstract

Juvenile rock fish Sebastes schlegelii were exposed to dietary lead (Pb2+) at concentrations of 0, 120, and 240 mg/L and ascorbic acid (AsA) at 100, 200, and 400 mg/L for 4 weeks. The stress indicators, plasma cortisol and heat shock protein 70 of S. schlegelii were also analyzed. Plasma cortisol and HSP 70 were considerably increased following exposure to dietary Pb, and high levels of ascorbic acid were highly effective in alleviating these elevations in cortisol and HSP 70. Lysozyme activity was significantly increased. The results of this study indicate that dietary Pb affects the stress indicators and high doses of AsA supplementation were effective in attenuating the changes brought about by dietary Pb exposure.

Introduction

Heavy metal pollution in aquatic environments is a critical environmental concern, as the metals can accumulate in aquatic organisms and humans via the food chain, creating a risk to human health. Among the metals, Pb is one of the most toxic to aquatic organisms[1]. Pb is a naturally occurring substance, released as a consequence of geological weathering and volcanic activity, however, high concentration Pb in aquatic environments are caused by anthropogenic activity such as the manufacture of batteries, cement, and paint. The toxic effects of Pb observed in aquatic animals include numbness, lord oscoliosis, muscular atrophy, caudal fin degeneration, and loss of equilibrium[1].

The Pb exposure in aquatic animals induces non-specific toxicity that affects various physiological systems[2]. Symptoms of Pb toxicity include cognitive dysfunction, neurological damage, calcium homeostasis alterations, and oxidative damage, as well as muscular atrophy, black tail, fin degeneration, and hyperactivity[1]. Pb toxicity can also induce stress in exposed animals, and cortisol and heat shock protein 70 (HSP 70) are considered sensitive and reliable indicators of this stress response. Cortisol is a major steroid hormone secreted in the interregnal tissue of teleosts. Elevations in plasma cortisol levels are closely associated with stress responses induced by toxicants. These elevations in cortisol effectively increase glucose and lactate levels in the plasma, and are under the control of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) that is released from the pituitary gland[3]. HSP 70 is a protein that is expressed by various biotic and abiotic stress factors. The HSP 70 response in fish is highly associated with environmental contamination[4]. A positive correlation between elevated HSP 70 and exposure to toxicants has been demonstrated in many studies[5], and exposure to heavy metal environmental contamination specifically, causes increased levels of HSP 70. Therefore, cortisol and HSP 70 could potentially be good biomarkers of stress in aquatic animals exposed to toxic substances.

Ascorbic acid (vitamin C or AsA) is an essential nutrient for proper metabolic function and immunity, as well as growth and development in teleosts. It is also associated with metabolism and detoxification of various metals[6]. Although there have been few reports on the effects of AsA supplementation on metal immune response and stress indicators in fish exposed to metal, this form of supplementation is likely to exhibit favorable effects.

In Korea, the rockfish, Sebastes schlegelii, is one of the most commonly cultured fish owing to its high demand, good flesh qualities, and rapid growth rate. As yet, no studies have been carried out to examine the toxic effects of dietary Pb exposure on S. schlegelii. In Korea, the level of Pb in coastal sediments ranges from 9.6 to 92.0 mg/L[7], and higher concentrations of Pb should be tested to assess Pb toxicity in aquatic animals within the context of ecotoxicology. AsA supplementation is a major method used to attenuate the toxic effects on most animals. In the present study, AsA concentrations of 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg were applied in combination with Pb concentrations of 0, 120, and 240 mg/kg, to examine the differences in Pb toxicity according to varying levels of AsA supplementation. Moreover, toxicity was assessed using immune responses and stress indicators of S. schlegelii.

Materials and Methods

Experimental fish and conditions

Juvenile Sebastes schlegelii from a floating fish cage in Tongyeong, Korea were prepared for this study. After the acclimation period for 2 weeks under laboratory conditions (temperature 19.0 ± 1.0 °C; pH 8.1 ± 0.5; salinity 33.2 ± 0.5%; dissolved oxygen 7.1 ± 0.3 mg/L; chemical oxygen demand 1.15 ± 0.2 mg/L), the exposure experiment was conducted. 90 healthy fish (body length, 11.3 ± 1.2 cm; body weight, 32.5 ± 4.1g) were randomly selected. The Pb exposure concentrations were 0, 120, 240 mg/kg, and the ascorbic acid (AsA) exposure were 100, 200, 400 mg/kg. The daily amount of feeding was 2% body weight (two 1% meals per day). After the exposure at 2 and 4 weeks, S. schlegelii were anesthetized to obtain the blood and tissues for experimental analysis.

Feed ingredients and diets formulation Composition of the feed is demonstrated in Table 1. All feeds contain the casein, fish meal, wheat flour, fish oil, cellulose, corn starch, vitamin premix (vitamin C-free), and mineral premix of proper contents. To adjust the respective concentrations of Pb and AsA, the Pb premix (20,000 mg Pb/kg) and AsA premix (20,000 mg AsA/kg) were used. After making the respective concentrations of the feeds, the actual Pb and AsA concentrations of the feeds were analyzed using ICP-MS (ELAN 6600DRC) and HPLC (Agilent 1200 series), and the actual concentrations are shown in Table 2.

Table 1: Formulation of the experimental diet (% dry matter).

| Ingredient (%) | Concentration (mg/kg) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0V1 | M0V2 | M0V3 | M1V1 | M1V2 | M1V3 | M2V1 | M2V2 | M2V3 | |

| Casein1 | 33.0 | 33.0 | 33.0 | 33.0 | 33.0 | 33.0 | 33.0 | 33.0 | 33.0 |

| Fish meal2 | 23.0 | 23.0 | 23.0 | 23.0 | 23.0 | 23.0 | 23.0 | 23.0 | 23.0 |

| Wheat flour3 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| Fish oil4 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| Cellulose1 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 1.8 |

| Corn starch3 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | |

| Vitamin Premix (Vitamin C-free)5 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Mineral Premix6 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Lead Premix7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Ascorbic acid Premix8 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

1United States Biochemical (Cleveland, OH); 2Suhyup Feed Co., Ltd., Gyeong Nam Province, Korea; 3Young Nam Flour Mills Co., Pusan, Korea. 4Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO; 5Vitamin Premix (vitamin C-free) (mg/kg diet): dl-calcium pantothenate, 400; choline chloride 200; inositol, 20; menadione, 2; nicotinamide, 60; pyridoxine•HCl, 44; riboflavin, 36; thiamine mononitrate, 120, DL-a-tocopherol acetate, 60; biotin, 0.04; folic acid, 6; vitamin B12, 0.04; retinyl acetate, 20000IU; cholecalciferol, 4000IU. 6Mineral Premix (mg/kg diet): Al, 1.2; Ca, 5000; Cl, 100; Cu, 5.1; Co, 9.9; Na, 1280; Mg, 520; P, 5000; K, 4300; Zn, 27; Fe, 40; I, 4.6; Se, 0.2; Mn, 9.1. 7Lead Premix: 20,000 mg Pb/ kg diet. 8Ascorbic acid Premix: 20,000 mg ascorbic acid/ kg diet (M0: Pb 0 mg/kg, M1:Pb 120 mg/kg, M2: Pb 240 mg/kg; V1: AsA 100 mg/kg; V2: AsA 200 mg/kg; V3: AsA 400 mg/kg)

Table 2: Analyzed dietary concentration (mg/kg) of each source.

| Diets (mg/kg) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0V1 | M0V2 | M0V3 | M1V1 | M1V2 | M1V3 | M2V1 | M2V2 | M2V3 | |

| Pb concentration | 0 | 0 | 0 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 240 | 240 | 240 |

| Actual Pb level | 2.1 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 121.5 | 117.8 | 118.2 | 237.2 | 236.7 | 241.9 |

| AsA concentration | 100 | 200 | 400 | 100 | 200 | 400 | 100 | 200 | 400 |

| Actual AsA level | 87.8 | 168.5 | 359.5 | 91.2 | 176.8 | 364.5 | 89.3 | 162.5 | 372.8 |

Plasma cortisol

After collecting blood samples of S. schlegelii, samples were centrifuged to separate plasma from blood. Cortisol concentrations in plasma were analyzed using a monoclonal antibody enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) quantification kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Inc., Farmingdale, NY, USA). Plasma samples were added in anti-Mouse Ig G microtiter plate. After experimental treatment, the plate was measured at 405 nm optical density.

Heat shock protein 70 (HSP 70) gene expression

Liver tissues of S. schlegelii were used to measure the HSP 70 gene expression. RNA purification kit (Real Biotech Corporation, Taipei, Taiwan) was used to obtain total RNA from the liver tissues. Purified RNA was transformed to cDNA using cDNA synthesis kit (Enzo Life Sciences Inc., NY, USA). To determine the HSP 70 gene expression, the primers (18s rRNA and HSP 70) are demonstrated in Table 3. Real-time PCR assay were carried out in a quantitative thermal cycler (Light Cycler® 480 II, Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Rotkreuz, Switzerland). The real- time qPCR amplification began with 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation of 10 s at 95 °C, annealing of 10 s at 60 °C, and extension of 10 s 72 °C. To express the mRNA expression concentrations, the comparative CT methods (2-ΔΔCT method) were used.

Table 3: Primers used for real-time qPCR.

| Gene | Sequence | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| 18s rRNA | Fw : TGAGAAACGGCTACCACATC | 100 |

| Rv : CAATTACAGGGCCTCGAAAG | ||

| HSP 70 | Fw : GATGCAGCCAAGAACCAGGTGG | 144 |

| Rv : GCTTCCCTCCATCTCCGATCACC |

Lysozyme activity: The plasma and kidney were used to analyze the lysozyme activity of S. schlegelii. The kidney tissues were homogenized using 0.004M phosphate buffer, and the supernatant was attained after centrifuging the homogenizing solution at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. Lysozyme activity was analyzed using the method of Ellis[8]. Protein concentration was calculated by the Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories GmbH, Munich, Germany), and the lysozyme activity values were expressed as μg/ml and μg/g.

Statistical analysis: The experiment was conducted in exposure periods for 4 weeks and performed triplicate. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS/PC+ statistical package (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Significant differences between groups were identified using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons or Student’s t-test for two groups. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

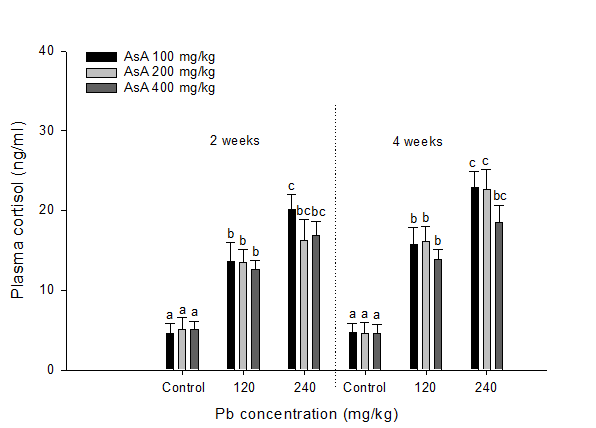

Plasma cortisol

Plasma cortisol levels in S. schlegelii exposed to dietary Pb and AsA supplementation is presented in Figure. 1. A significant increase in plasma cortisol was observed following exposure to 120 mg/kg Pb at two and four weeks, respectively. After two weeks exposure to 240 mg/kg Pb exposure, the groups supplemented with 200 and 400 mg/kg AsA, respectively, showed notably lower plasma cortisol levels than the group supplemented with 100 mg/kg AsA. Similarly, after four weeks, the group supplemented with 400 mg/kg AsA showed significantly lower plasma cortisol levels than those supplemented with 100 and 200 mg/kg AsA, respectively.

Figure 1: Plasma cortisol levels in rockfish, S. schlegelii exposed to different concentrations of dietary Pb and AsA for four weeks. Values with different superscripts are significantly different at two and four weeks (P < 0.05) as determined by the Tukey’s multiple range test.

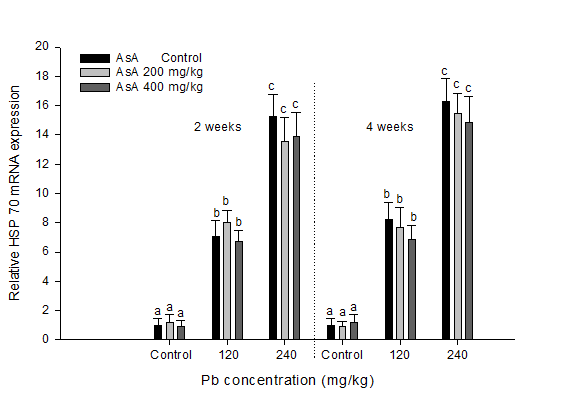

Heat shock protein 70 gene expression

Relative HSP 70 mRNA gene expression in S. schlegelii following exposure to dietary Pb and AsA supplementation is presented in Figure. 2. A substantial increase in relative HSP 70 mRNA was observed on exposure to dietary Pb. However, these alterations were not dependent on the various levels of AsA supplementation.

Figure 2: Relative expression of HSP 70 mRNA in rockfish, S.schlegelii exposed to different concentrations of dietary Pb and AsA for four weeks. Values with different superscripts are significantly different at two and four weeks (P < 0.05) as determined by the Tukey’s multiple range test.

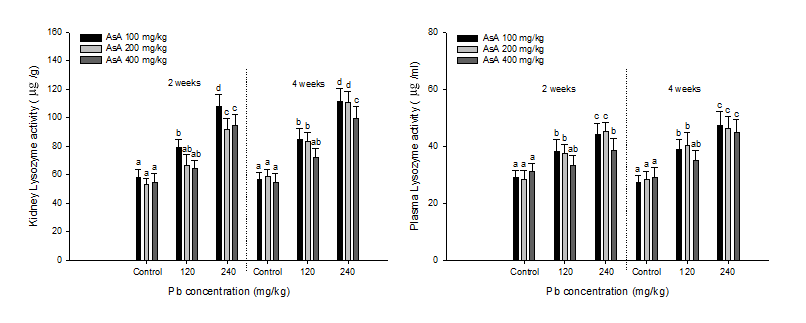

Lysozyme activity

The lysozyme activity of kidney and plasma in S.schlegelii with dietary Pb exposure and AsA supplementation is shown in Figure 3. For the kidney lysozyme of S. schlegelii, a notable increase was observed after two weeks over 120 mg/kg Pb with 100 mg/kg AsA and in the concentration of 240 mg/kg Pb with 200 and 400 mg/kg AsA. After 4 weeks, the kidney lysozyme was elevated by the Pb exposure over 120 mg/kg with 100 and 200 mg/kg AsA and in the concentration of 240 mg/kg with AsA 400 mg/kg. For the plasma lysozyme activity, an increase was observed over 120 mg/kg Pb with 100 and 200 mg/kg AsA and in the concentration of 240 mg/kg Pb with AsA 400 mg/kg after 2 and 4 weeks.

Figure 3: Lysozyme activity of rockfish, S. schlegelii combined exposed to the different concentration of dietary Pb and AsA for 4 weeks. Values with different superscript are significantly different in 2 and 4weeks (P < 0.05) as determined by Tukey’s multiple range test.

Discussion

The Pb exposure in aquatic animals causes stress, by affecting physiological systems in addition to other toxic symptoms, such as cognitive dysfunction, neurological damage, and oxidative stress[2]. Plasma cortisol is a critical parameter of functional changes in the hypothalamo-pituitary-inter-renal (HPI) axis in fish that regulates energy mobilization and ion homeostasis in fish, and is stimulated by exposure to stressors[9]. In the present study, exposure to dietary Pb induced a significant increase in cortisol levels of S. schlegelii. Pelgrom et al.(1995)[10] reported increased plasma cortisol levels in tilapia, Oreochromis mossambicus exposed to Cu.

In the present study, AsA supplementation notably attenuated increases in cortisol levels in S. schlegelii exposed to dietary Pb. Broudy et al. (2002) reported that high levels of AsA supplementation might affect stress-related central neurotransmission or increase oxytocin secretion. These are protective mechanisms in response to stress. Zhou et al. (2003)[11] also reported that AsA supplementation attenuate cortisol increase in turtles, Pelodiscus sinensis under condition of acid stress, indicating the positive effects of AsA on cortisol levels. Based on the present results, exposure of S. schlegelii to dietary Pb induces elevated cortisol levels by stress, and AsA supplementation significantly reduces the stress-induced release of cortisol. Exposure to dietary Pb also induces a significant increase in levels of heat shock protein 70 (HSP 70) in S. schlegelii. Williams et al. (1996)[12] reported that waterborne and dietary metal exposure in rainbow trout, O.mykiss induced significant accumulation of HSP 70. This might represent a protective mechanism against stress-induced injury due to heavy metal exposure. Various levels of AsA supplementation had no effect on HSP 70 values in S. schlegelii, whereas exposure to dietary Pb induced substantial expression of HSP 70. Biomarkers have been used as sensitive indicators to monitor the toxic effects of pollution in the marine environment. Toxicants generally cause stress in biota of an ecosystem; therefore, substances released in response to stress, such as cortisol and HSP 70, can be valuable and reliable indicators of cellular stress in organisms[13].

The immune responses can suggest sensitive biomarkers to assess environmental pollution, and of the various markers, lysozyme in fish is a reliable indicator for monitoring the effects of environmental hazards[14]. Dietary Pb exposure induced a significant increase in the kidney and plasma lysozyme of S. schlegelii. In addition, the AsA supplementation was also effective to attenuate the lysozyme increase by the Pb exposure. Low and Sin (1998)[15] reported the increase in kidney lysozyme of blue gourami, Trichogaster trichopterus, when exposed to mercury.

In addition, exposure to dietary Pb caused significant elevations in stress indicators, such as cortisol and HSP 70. AsA supplementation effectively reduced the increased cortisol level following dietary Pb exposure, although no alterations were observed in HSP 70 expressions. Lysozyme activity was increased by dietary Pb exposure, and high doses of AsA supplementation were significantly effective in attenuating changes by dietary Pb exposure. As a result, we suggest that dietary Pb exposure is likely to have toxic effects on other experimental animals, and AsA supplementation is likely to effectively lower the effects of Pb-induced toxicity.

References

- 1. Kim, J.H., Kang, J.C. The lead accumulation and haematological findings in juvenile rock fish Sebastes schlegelii exposed to the dietary lead (II) concentrations. (2015a) Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 115: 33-39.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 2. Rabitto, I.S., Alves Costa, J.R.M., Silva de Assis, H.C., et al. Effects of dietary Pb (II) and tributyltin on neotropical fish, Hoplias malabricus: histopathological and biochemical findings. (2005) Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 60(2): 147-156.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 3. Gesto, M., Soengas, J.L., Miguez, J.M. Acute and prolonged stress responses of brain monoaminergic activity and plasma cortisol levels in rainbow trout are modified by PAHs (naphthalene, β-naphthoflavone and benzo(a)pyrene) treatment. (2008) Aquatic Toxicology 86(3): 341-351.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 4. Iwama, G.K., Thomas, P.T., Forsyth, R.B., et al. Heat shock protein expression in fish. (1998) Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 8: 35-56.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 5. Duffy, L.K., Scofield, E., Rodgers, T., et al. Comparative baseline levels of mercury, hsp70 and hsp60 in subsistence fish from the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta region of Alaska. (1999) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Toxicol. Pharmacol 124(2): 181-186.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 6. Kim, J.H., Kang, J.C. Influence of dietary ascorbic acid on the immune responses of juvenile Korean rockfish Sebastes schlegelii. (2015b) Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 27(3): 178-184.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 7. Lim, D.I., Choi, J.Y., Jung, H.S., et al. Natural background level analysis of heavy metal concentration in Korean coastal sediments. (2007) Ocean and Polar Research 29: 379-389.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 8. Ellis, A.E. Lysozyme assay. In: Stolen JS, Fletcher TC, Anderson DP, Roberson BS, van Muiswinkel WB, editors. (1990) Techniques in fish immunology. NJ: ISOS Publications 101-103.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 9. Gagnon, A., Jumarie, C., Hontela, A. Effects of Cu on plasma cortisol and cortisol secretion by adrenocortical cells of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). (2006) Aquatic Toxicology 78(1): 59-65.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 10. Pelgrom, S.M.G.J., Lock, R.A.C., Balm, P.H.M., et al. Effects of combined waterborne Cd and Cu exposures on ionic composition and plasma cortisol in tilapia, Oreochromis mossambicus. (1995) Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Pharmacology, Toxicology and Endocrinology 111: 227-235.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 11. Zhou, X., Xie, M., Niu, C., et al. The effects of dietary vitamin C on growth, liver vitamin C and serum cortisol in stressed and unstressed juvenile soft-shelled turtles (Pelodiscus sinensis). (2003) Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A 135(2): 263-270.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 12. Williams, J.H., Petersen, N.S., Young, P.A., et al. Accumulation of hsp 70 in juvenile and adult rainbow trout gill exposed to metal-contaminated water and/or diet. (1996) Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 15(8): 1324-1328.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 13. Sherman, M.Y., Goldberg, A.L. Cellular defences against unfolded proteins: A cell biologist thinks about neurodegenerative diseases. (2001) Neuron 29(1): 15-32.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 14. Kim, J.H., Kang, J.C. Oxidative stress, neurotoxicity, and non-specific immune responses in juvenile red sea bream, Pagrus major, exposed to different waterborne selenium concentrations. (2015c) Chemosphere 135: 46-52.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 15. Low, K.W., Sin, Y.M. Effects of mercuric chloride and sodium selenite on some immune responses of blue gourami, Trichogaster trichopterus (Pallus). (1998) The Science of the Total Environment 214: 153-164.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others