Clinical Translation of Tissue Engineered Medicinal Products

Sanjay Gottipamula

Affiliation

Sri Research for Tissue Engineering Pvt. Ltd, Sri Shankara Research Centre, Rangadore Memorial Hospital, Bangalore, India

Corresponding Author

Sridhar, K.N. Sri Research for Tissue Engineering Pvt. Ltd, Sri Shankara Research Centre, Rangadore Memorial Hospital, Bangalore - 560004, India; Tel: +91-080-41076759; E-mail: knsridhar@sr-te.com

Citation

Sridhar, K.N., et al. Clinical Translation of Tissue Engineered Medicinal Products. (2016) J Stem Cell Regen Bio 2(1): 38- 51.

Copy rights

© 2016 Sridhar, K.N. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Cell therapy; Clinical translation; Regulatory frame-work; Regulatory Challenges; TEMPs

Abstract

Tissue Engineering is a rapidly growing field with novel scientific concepts, new technological methods, and evolving regulatory policies for clinical translation. Most of the current basic regulations are taken from the pharma, bio-pharma, cell therapy with little modifications, and new inclusion for development of regulatory frame work for advanced therapeutic products. We propose to highlight the important concepts in the regulatory development for tissue engineered based medicinal products (TEMPs) without any compromise on Quality, safety and efficacy. Moreover, these evolving regulations should facilitate clinical transition to help large numbers of patients on conditionally or case-by-case basis, and accelerate the submission of on-line real-time safety and efficacy parameters. This review describes general regulations and its scientific concepts; specifically in the context of clinical translation for TEMPs. Importantly, this review highlights the need of regulatory development and support for sustenance of small and medium sized organizations without any compromise on safety and efficacy of the products. Furthermore, current clinical regulatory translational challenges and opportunities to articulate risk-benefit approaches by accessing its potential strength, efficacy or availability of standard therapy, safety of new product and its relevance’s with TEMPs are discussed.

Introduction

Tissue engineering is an interdisciplinary technology that combines the principles of life science, biomaterial engineering and clinical applications. It aims at assembly of biological substitutes that will restore, maintain and improve tissue functions following damage either by disease or trauma. Despite rapid progress in the tissue engineering application, there are no specific regulatory/mechanisms to provide a legal framework for introducing new or bio-similar like tissue engineering product into clinical practice[1]. This has resulted in slow approvals for TEMP, besides; expensive industrial regulatory approaches were introduced as essential regulatory requirements, in addition to various the social and ethical clearances[2]. There is need for the fast track approvals to test this innovative medicine to access in clinical trial based on risk-benefit ratio to the patients, as well as considering various factors such as availability and usability of existing standard therapy, cost, and economics.

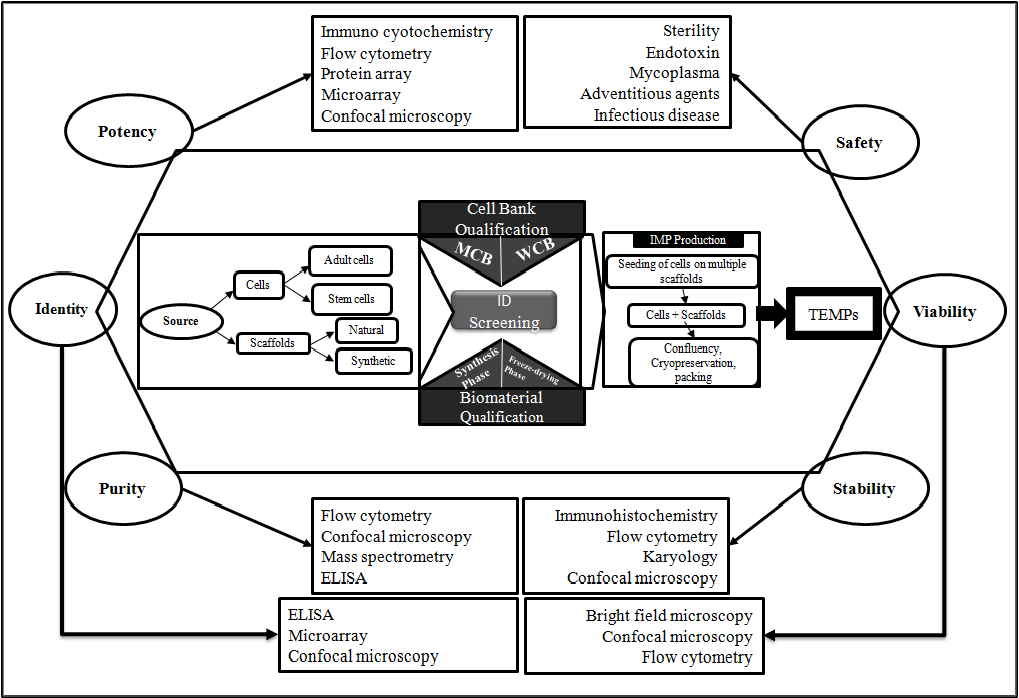

The current pharma, bio-pharma and cell therapy approaches focus on curing the disease and helping to restore cellular level function. On the other hand, the recent advances in interdisciplinary science not only enables for process and product characterization (Figure 1), but also develop innovative TEMPs that restore repair and regenerate the cells, tissues to retain and improve biological function. Besides, these TEMPs have potential to revolutionize the medical treatment to improve the quality-of-life to patients, where there are no standard therapies available or available treatments are expensive. For example Autologous adipose-derived regenerative cells (NCT01889888) for the treatment of urethral stricture. The standard surgical treatment is unable to prevent the fibrosis which calls for surgical interventions and increasing the cost to patients. Some of the innovative TEMPs like Tympanogen (Perf-FixTM) are becoming the new standard of care and drug-releasing scaffold and providing non-surgical treatment options for chronic tympanic membrane perforations. Thus these new products avoid post-surgical complication to the patients[3]. Some of the TEMPs uses the combination of standard surgical procedures and tissue transplantation, and has high potential to become alternative to reconstructive bio-surgeries. These innovative therapies are made available to potential patients in timely manner.

Figure 1: General process map and characterization of TEMPs: Overview of process from cell sourcing to IMP Production and intermediate bank/biomaterial qualification steps. Critical components for characterization are at six corners of hexagonal i.e., identity, potency, purity, safety, stability and viability demonstrate the quality and efficacy of process and product. Related techniques for each critical characteristics were displayed in box.

Abbreviations: ID-Infectious diseases; IMP- Investigational Medicinal Products; MCB-Master cell bank; TEMP-Tissue Engineered medicinal products; WCB-Working cell bank.

The TEMPs are combinations of cells and regenerative matrices, which involves the bioengineering approaches to engraft the biomaterial and cells to retain the tissue-level functions. The unique natures of the products are being convergent to traditional regulatory process for safety and efficacy evaluations. Understanding the regulatory requirements and meeting to reach the evolving regulatory expectation of TEMP during the transition period is even more difficult for start-up entrepreneurs or small companies in early stage of clinical trials. Further vast requirements on product development and pre-clinical data within defined time frame makes developers to evolve various adaptation strategies to complete clinical transitional phase of TEMPs. On the other hand, significant reduction in development time for acellular TEMP for tropical applications were expected[4,5]. Further, cell secretome of cell culture conditioned medium (CM) contains biological active substances and its activity were tested in many applications such as inhibition of stricture fibroblasts proliferation and migration[6]. These secretome of CM can be utilized for regenerative skin and wound healing products that might have a shorter regulatory path and maximise the scalability. Moreover, academicians, universities, spin-off companies and small and medium size entrepreneurs (SME) are highly active in the development of advanced therapies, innovative medicines and tissue engineering products for rare diseases and various clinical indications. The SMEs account for about half of all new medicines and bio-similar TEMPs under development in European nation[7]. These products have sufficient potential to bring significant clinical benefits and cost reduction of standard therapy to patients and address unmet medical needs and successful clinical translational developments in the interests of patients[2]. But the product developed by micro, small and medium sized enterprises, university and academia lacks real-time regulatory experiences and it looks challenging[4]. Besides, non-routine personalized patient-specific hospital exemption therapies makes ambiguity and confusions with classical transplant/transfusion methodologies. However, these exemptions from mandating GMP, assessment of safety, efficacy and clinical end-points dilute the standards/loop hole for regulations and enhance the risk to impair R&D investments, but needs to meet certain requirements of regulations and safety compliances[8].

Overview of general process of regulations for medicinal products

The comprehensive government regulations and policies are lay down to maintain the standards for pharmaceuticals, biopharmaceuticals and to some extent for cell therapeutics exist in India, US and many other nations. Most of the governing basic regulations were translated to frame a basic legal out-look to the TEMPs inviting lengthy and arduous regulatory process. On the contrary, need arises to learn from the experiences of the other related field of bio-pharma, cell therapeutics to overcome the challenges and to strengthen the manufacturing standards of TEMPs. The core requirements, procedures of each sector (Biopharma, Cell therapeutics and TEMPs) are different in terms of product definition, raw material usage to clinical trial design that are depicted in (Table I). These 3 sectors of next generation therapeutics have attracted a great deal of attention, in spite of variable differences in the concepts, product design and product manufacturing. The extent of comprehensiveness in product characterization program minimize the risk that are likely to be associated for new innovative products and increase safety, quality, efficacy and consistency in clinical out-come.

Table I: Characteristics of Bio-pharma, cell therapeutics and TEMPs; The main differences among biological drugs, cell therapeutics and Tissue engineering medicinal Products (TEMPs) are summarised[9,10].

| SL | Properties | Bio-pharma | Cell Therapeutics | TEMPs |

| 1 | Product definition | A well characterized biomolecules with well-defined composition; established proof of concept; Mechanism of action by biochemical activity within the body. Primary intended use through biochemical activity and sometimes attain its activity by being metabolized. | Adult cells/stem cells of Moderately characterized, identity established, MOA by paracrine secretion or by cell itself. | Tissue engineered Medicinal products (TEMPs) are complex products that are composed of combinations of cells, soluble biomolecules and biomaterial. |

| 2 | Raw material | Active therapeutic biomolecules are synthesized by low risk, well characterized starting material | Final therapeutic cells are derived from moderate risk material like bone marrow etc. | Starting material are cells and sometimes scaffold derived from biomedical waste like placenta, amnion etc. |

| 3 | Sterility Assurance | End product is sterile filtered and products are high sterility assurance level. | Aseptic processing allows limited sterility assurances of final product and the final product cannot be sterile filtered. | Aseptic processing of cells allows limited sterility assurances and biomaterial part has substantial sterility assurances level, as these can be filter sterilized or gamma irradiated. Overall TEMPs have moderate sterility assurances level. |

| 4 | Process scale-up | Process is highly feasible for scalability | Moderately feasible for scalability; Scale-out can be possible. | Scale-out process. Highly feasible for personalized medicine |

| 5 | In-process controls | In-process controls are well established | Moderately established. | Moderately established |

| 6 | Product purification requirements | The intermediate product produced after upstream processing led to serial chromatographic and non-chromatographic purification steps | In some cases, the required cells can be selected through Magnetic activated cell sorting systems | No specific final product purification steps; however the intermediate product (cells and biomaterial) can have purity or impurity profiles |

| 7 | Fill and finish | Regularized to cope up to fill 50,000 to 1 million doses | Time based filling process, Single batch provides 30-50 doses | Not well established |

| 8 | Product shelf-life | Most biologics are stable for 2 to 5 years | Cell therapy Products are stable for 1 to 2 years | Not well established |

| 9 | Product storage | Most of the products stable at 2- 8 or -20° C | Vapour phase of Liquid Nitrogen | Vapour phase of Liquid Nitrogen |

| 10 | Product characterization - Testing and release criteria | High molecular weight proteins as drug and has heterogeneous structure, but Harmonized scientific testing standards or specifications are in practices for Biologics. | Cell dose in terms of cell number, and important characteristics are cell viability, cell identity, cell safety and cell stability. | Testing is limited to bioactivity of cells and biomaterials. Regenerative cell matrices and TEMPs are moderately established. |

| 11 | Potency assay | Potency test are well established and regulatory and scientific methodologies were defined. | Potency assays for cell therapy are evolving based on regulatory and scientific consideration | It is quite difficult to measure the intended biological activity of TEMPs |

| 12 | Delivery | Mostly parental, IV, IM | Site specific and IV | Site Specific - tissue replacement to retain function |

| 13 | Clinical efficacy end points | Efficacy is direct clinical benefit and disease free survival and improving the quality of life. Advantage is precisely measured. | Clinical efficacy is improving the quality of life. | Efficacy end points in context of cell- and tissue-specific endpoints like biochemical, morphological, structural and functional parameters are to be relevant for the targeted/stated therapeutic claim. |

| 14 | Bioequivalence studies | Available and routinely done for biosimilar products | Guidelines still not established | not available |

| 15 | Drug metabolism | Pharmacokinetic studies (PK) such as drug metabolism, excretion studies and classical carcinogenicity studies are well established. Pharmacodynamics(PD)are well established | Pharmacokinetics studies in terms of in-vivo cell migration, differentiation studies. | Recent reflection paper on TEMPs reveals bio distribution, longevity and possible degradation of the TEMP and its components. PK and PD are interlinked. |

| 16 | Immunogenicity | Host cell proteins (HCP) are immunogenic and proof of negligible level of HCP in final product are well established | Mixed Lymphocyte reaction assay are well established, to some extent flow cytometry assay are streamlined | MLR assay for scaffolds and cells can independently accessed. Immunogenicity particular to TEMPs are moderately studied for allogeneic use. |

| 17 | Dose finding studies | Applicable and depends on relative potency of proteins | Applicable and depends on number of cells its paracrine factors | Various cell densities and concentration of non-cellular constituents to be regularized in pre-clinical studies. |

| 18 | Pre-clinical testing | Preclinical testing and methodologies follows well established guidelines. | The species specificity of cells in animal model may not resemble to clinical situation. Generation of biologically relevant animal models are challenging. | The species specificity of cells in animal model may not resemble to clinical situation. Generation of biologically relevant animal models are challenging. |

| 19 | Regulatory Process | Regulatory process is well defined with a set of guidelines for similar biologics | Regulatory process is moderately defined with guidelines and guidelines for similar cell therapy products yet to establish | Most of Regulatory process is defined by using classical pathways. Needs exclusive guidelines for innovative TEMPs and bio-similar TEMPs. |

| 20 | Clinical Study Design | Double blinded randomized Placebo controlled study (RCT)design are routinely used methodology | Double blinded RCT design applicable, but exist many challenging to implement, as most of the cell therapeutics requires pre-infusion washing and concentration of cells. | Due to surgical intervention during TEMP administration, It is not possible to do Double blinded RCT. |

Table II depicted the overview of classical drug development and traditional regulatory process. The drug development starts with basic research, discovery and non-clinical and clinical trials. The regulatory process comprises of the application to conduct clinical trials, clinical trial execution and pre-market approval and drug release. The traditional drug development and approval process may take 6-11 years for clinical phase translation with an approximate cost of 100 million dollars, after filing an Investigational New Drug Application (IND)[10]. Besides, manufacturers spend another 1-6 year for demonstration of product safety and efficacy in pre-clinical testing. The first phase of clinical transitional development begins after approval of IND by the FDA and by Institutional Review Board. The short-term (1-2 years) clinical phase-I of product on 20 to 80 healthy volunteers to determine basic pharmacological and toxicological information with regards to safety. In phase-II, the product is tested for safety and efficacy on small-scale volunteers of targeted populations of 100-300 numbers to find the optimal dosage level. The large-scale testing for safety and efficacy on 1000-3000 targeted population in phase-III, especially to get the results to decide its potency and intended purpose[9]. The FDA review meeting on clinical trials results and future developments at each phase will bring harmonized understanding between 2 parties (sponsor and regulatory agency) that accelerates to establish the safety and efficacy without any bias on addressing the regulatory non-compliance. There are certain instances in India, the Licensing authority permit to repeat the phase-I or phase-II, where the drug substances discovered in countries other than India. In certain conditions, phase-II will be 10-12 patients of multi-centric trials. Similarly, phase-III trials for at least 100 patients distributed over 3-4 centres[10]. Although, surrogate endpoints or markers are often expensive and time consuming to measure may help to enhance and track the effectiveness of the drug in post-marketing studies. The assurances of clinical data quality, validity in clinical trials are regulatory decision making points[11]. Therefore, it is necessary to assess the clinical trial progress through several clinical trial reviews, site visits and audits by the sponsors.

Table II: General drug development process

| Stages | Process of drug development | Production Scale | Process optimization | |

| Basic Research | Disease pathophysiology | Research-scale | ||

| Idea generation | ||||

| Literature Search | ||||

| Concept Generation | ||||

| Discovery | Research process | Lab-scale | ||

| Strategically thought | ||||

| Out of box thinking and execution | ||||

| Screening/feasibility analysis | ||||

| Lead candidates (one or two types) | ||||

| In-vitro safety studies | ||||

| In-vitro concept demonstration | ||||

| Non-Clinical studies | Stage-1 | General – In-vivo safety studies | Product Characterization, Testing and Release | |

| Stage-2 | Tumorogenecity studies | |||

| Stage-3 | Genotoxicity studies | |||

| Stage-4 | Multi-route administration studies | |||

| Stage-5 | Safety of 10X of therapeutic dose | |||

| Stage-6 | Non-clinical POC (1 species) | Pilot - Scale | ||

| Stage-7 | In-vivo models | |||

| Stage-8 | Non-clinical POC ( more than 2 species) | |||

| Clinical Trials | Phase-I | In-vitro-safety studies | ||

| In-vivo model | ||||

| In-vivo potency assay | ||||

| Phase-II | Bio-distribution studies | Process Development - feasibility analysis and selection from various options for large scale batches/Clinical Scale | ||

| Pharmacokinetics | ||||

| Pharmacodynamics | ||||

| Human - Dose finding studies | ||||

| Human - Efficacy Studies (small scale) | ||||

| Phase-III | Clinical proof (Randomized double blinded studies) | Commercial Scale - Scale-up/ Scale out | ||

| In-vivo model | ||||

| In-vivo potency/efficacy assay | ||||

| Human - Dose finding studies | ||||

| Human - Efficacy Studies | ||||

| Authorization | Long term efficacy and follow up | |||

| Post-Launch | Phase-IV | |||

Current clinical translations of TEMPs are not clear and ambiguity exists for approval process, as these products are combinations of pharmaceuticals, biologics, medical devices and surgical procedures. On the other hand, each section of above combinations is driven by set of regulations and these regulations are different in different nations. Many of these TEMP’s may become integral part of the body after implantation and major target populations are the patients with serious diseases[12], for whom a rarely conventional therapy exists. These includes the tissue-engineered bone, blood vessels, liver, muscle, and even nerve conduits are promising output as TEMPs and has significant medical and market potential in this technology[13]. On the contrary, European community has unified regulatory framework for medical devices, tissue engineering and medicinal products. The initiative were taken to identify and address the regulatory gap between medical devices (93/42/EEC) and medicinal products (2001/83/EC), as TEMPs is emerging alternative for surgical reconstruction that are functional from the beginning and grow to required functionality. Public consultations were made on regulation of ATMP for harmonization of development requirements among different countries.

Regulatory challenges

In European Union, the EMA has initiated an umbrella classification, where TEMPs are sub-categorised under Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMP)[14]. These ATMP classifications are as follows:

1. Gene therapy medicinal product (GTMP) contains an active substance of a recombinant nucleic acid used for regulating, repairing, replacing of genetic sequences and its therapeutic, prophylactic or diagnostic effects are due to the recombinant nucleic acid sequences.

2. Somatic cell therapy medicinal product (ScTMP) are of cells or tissues that have been subject to substantial manipulation (cutting, grinding, shaping, centrifugation, soaking in antibiotic or antimicrobial solutions, sterilization, irradiation, cell separation, concentration or purification, filtering, lyophilization, freezing, cryopreservation, and vitrification) to alter its innate biological characteristics, physiological functions relevant for the intended clinical use and its therapeutics effects are due to the pharmacological, immunological or metabolic action of its cells or tissues.

3. Tissue engineered products (TEMPs) are of engineered cells or tissues are subject to substantial manipulation with a view to regenerating, repairing or replacing a human tissue. A tissue engineered product may contain cells or tissues of human or animal origin, or both. It may also contain additional substances, such as cellular products, bio-molecules, biomaterials, chemical substances, scaffolds or matrices.

4. Combined advanced therapy medicinal product (CATMP) are combination of one or more medical devices with implantable medical products as an integral part of the complete product. Its cellular or tissue part must be liable to act upon the human body with action to that of the devices.

The ATMP classification is a useful tool for applicants to initiate the dialogue on the product developments aspects with regulators. A consolidated regulatory aspect for the development of ATMPs came into force in 2008[15]. Still borderline areas of cosmetics or medical devices, transplants may arrive, even after proactive regulatory evidences for clinical development of ATMPs[16]. These cumbersome and clumsy regulatory procedures were criticized[17]. On the other hand, there is an ambiguity in terminology of Tissue Engineering and regenerative medicine can lead to undistinguished boundaries between them. On the contrary, the ATMPs were simplified and classified based on degree of manipulations into several levels. Table: III defines the various levels of ATMP products, which helps in designing legal and regulatory framework based on level of intensity of manipulations. Further, these TEMPs were sub-classified based on risk/rejection possibilities. a) Autologous cells loaded on natural biomaterials/synthetic materials, b) Allogeneic cells loaded on scaffolds, c) Autologous multiple cell types (epithelial cells and stem cells) on scaffold, d) Non-autologous multiple cell types (epithelial cells and stem cells) on scaffold.

Table III: Classification of ATMPs based on “degree of manipulations”.

| Category | Requirements | Example |

| Level -1 | Hospital Exemptions with high assurances on safety and compliances. Lowest possible risk, low levels of oversight. Treatments methodologies and product manufactured by a medical practitioner for use on individual patients. Statement of compliance by practitioner required. No product dossier. | (platelet therapy, PRP etc) |

| Level -2 | Acelluar Scaffolds a) Synthetic with one proteins/Growth factor b) Synthetic with multiple proteins/Growth factors c) Nature Scaffolds - Well characterized natural or synthetic scaffolds. Information on safety, quality, and efficacy must be presented in dossier. |

Biosynthetic scaffolds/human amnion based scaffolds etc |

| Level -3 | Products manufactured with minimal manipulation intended for homologous use (homologous use means use in the tissue of origin to carry out the same biological function of the cell or tissue that is harvested). Require entry into India FDA and meeting good manufacturing practice standards. | Mononuclear cells non-cultured cells /autologous cells on collagen matric at the site of injury |

| Level -4 | Autologous cultured cells for 3 to 4 passages, characterized (more than minimal manipulated, safety, quality and efficacy must be presented in dossier. | Autologous therapy (MSCs) |

| Level -5 | Non-Autologous cultured cells for 4 to 5 passages, characterized, (more than minimal manipulated, and safety, quality, efficacy must be presented in dossier). | Allogeneic cell therapy - stem cells cultured for P4 or P5 |

| Level -6 | Animal derived materials – bovine collagen, | Atlas wound matrix (KGN dressing), porcine collagen |

| Level -7 | Combination of cells and biomaterials, Information on safety, quality, and efficacy must be presented in dossier. | Scaffolds and cell based products |

| Level -8 | Genetically modified products, Product requires the highest level of assessment. | Glybera® (alipogene tiparvovec),StrataGraft |

The new paradigm for bioengineering and implantation of simple body parts (vessels, bones, skins and cornea) were begun before the discovery of stem cells[18]. But the specified regulatory framework are still in nascent stage of development, where more emphasis are given on cell therapy aspects and clubbed as ATMP in Europe, stem cells and cell based products (SCCP) in India, and cellular and gene therapy (HCTPs)/TEMP working group in US. Experts opinion/interpretation and FDA feedback requirements in early stage process development enhances efficient clinical trial progression, as there is an overlap between reconstructive surgery and TEMPs[19]. Besides, hospital exemptions Under Article 3 (7) of 2001/83/EC from central authorisation within the same Member state hospital for customized patient therapy generate a parallel medicinal product status. In such cases, evidences of efficacy are more difficult to establish and lacks harmonization in these approaches.

The major manufacturing constraint involves scale-up, consistency, repeatability, reproducibility, immature production technologies, process variability, process validation and potency testing related to clinical outcome. Moreover, the critical process controls to be integrated and automated to enhance cGMP compliances for large scale commercial manufacturing[20,21]. On the other hand, the drug dose requirements of TEMPs and severity of the condition of recipient varies from patient to patient is critical variable factors that impact the clinical outcome. For example, the potency and safety of the TEMPs delivered to the burn-injured patients are depends on intensity of the secondary infections. In such cases, product related complications due to infection may affect the health of patients[22]. The regulating the control of product for “intended use” is another bottleneck issue. Even though, the TEMPs administration to patients based on risk/benefit ratio, some TEMPs carries some level of xenotransplantation risk, when applied to population at large, if the live potentially infectious animal source materials are used. For example, Latent virus’s infections that arise from source material contamination of certain donors of allogeneic origin are potential challenges. Further, the sudden unknown cell amplification leading to cancer due to yet unknown cell-scaffold interactions. Moreover, the risk of regeneration failure and graft rejection because of failure in understanding the specific biocompatibility requirements of TEMPs[23]. Hence, scientific understanding of the process is required to implement the cGMP, and regulatory standards to meet the safety and efficacy of TEMPs.

Developer related challenges are difficult to accept the new standards and requirements, limited resources and huge workload in SME. On the other hand, different nations have different ethical point of view to use cell-based products or discard biomaterials and no globalized ethical standards for cell sourcing etc. Limited resources to get funding for clinical trials, short shelf-life and expensive testing cost per batch for autologous therapies. Further, difficult to get medical reimbursement from insurances to patients undergoing novel drug therapies are some of the socio-economic challenges. There is no harmonization across the clinical trial requirements in various nations are one of the critical legal and regulatory challenges.

Regulations - similar biologics to like similar TEMPs

In pharmaceuticals, the reformulated products and generics tends to have shorter regulatory paths and less clinical development time for product launch. Hence these products have regulatory road-map, which enables the better compliances, safety and quality, besides cost-effectiveness. Similarly, polices and guidelines for similar biologics reveals that the similarity through extensive characterization - molecular and quality attributes with regard to references biologics. Extent of testing and characterization of similar biologics is likely to be less than that of references biologics. It needs the sufficient data to ensure that the product meets acceptable levels of safety, efficacy and quality[24]. Any significant differences in safety, efficacy and quality leads to more extensive pre-clinical and clinical studies and are not qualified as similar biologics. In this context, USFDA has published the encouraging guidelines to enhance the bio-similar manufacturing in USA[25]. Currently, CDSCO has been treating the stem cells and cell therapy/TEMPs as new drugs[26], even though there are several references to TEMPs already existing in global market (refer Table IV). Based on similar biologics regulatory pathway, there is a compelling need for transition of governing principles for cell therapy and TEMPs bio-similar products.

Table IV: Various TEMPs and cell therapy products in market and in clinical trials (as on Feb 2016).

| Company Name | Brand Name | Product Type | Indications | Comments | Status |

| Vericel/Genzyme | Epicel® | Cultured epidermal autografts, ex vivo in the presence of proliferation-arrested mouse fibroblasts. | Deep Dermal or Full Thickness Burns | Cleared as a Humanitarian Use Device; | Marketd/FDA approved |

| Osiris Therapeutics, Inc | Grafix® | Grafix® is Grafix is a cryopreserved placental tissue allograft. | Chronic ulcers of skin; Diabetic foot ulcers | NA | FDA approved |

| MacroCure | CureXcell™ | CureXcell™ is an allogenic mixture of WBC indicated for lower extremity chronic ulcers. | Chronic and hard to heal wounds | Clinical trials in Israel have shown a 90% reduction of mortality in patients with deep sternal wound infections and a markedly improved healing rate compared to severe pressure ulcers. | Approved in Israel, but recent phase-III results on Diabetic foot ulcers did not meet its study endpoints. |

| Organogenesis Inc. | Apligraf ® | Living, bi-layered skin substitute (bioengineered skin) derived from Neonatal foreskin fibroblasts and keratinocytes embedded in a Collagen I matrix. | Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Venous Leg Ulcers | The lower dermal layer combines bovine type 1 collagen and human fibroblasts. The upper epidermal layer is formed by multiplying human keratinocytes. | Marketed, FDA approved |

| Organogenesis Inc. | Gintuit | Neonatal foreskin derived fibroblasts and keratinocytes embedded in a Collagen I matrix | Gingival Regeneration | GINTUIT™ will help dental surgeons generate new gum tissue for their patients without turning to palatal graft surgery. | FDA approved |

| Forticell Bioscience | OrCel® | Bi-layered cellular matrix with human epidermal keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts in a Type I bovine collagen sponge | Epidermolysis Bullosa | Humanitarian Use Device. | FDA approved |

| Venous Leg Ulcers | NA | Pre-Market Approval Filed | |||

| Diabetic Foot Ulcers | NA | Phase III Clinical Trials | |||

| Holostem | Holoclar® | Autologous Limbalepithelial cells on fibrin scaffold | severe limbal stem cell deficiency | NA | Conditional approval - EMA |

| UroTissGmBH | MukoCell® | Cultured Oral mucosa epithelial cells | Urethral Strictures | NA | Certified for use in Germany |

| Avita Medical | ReCell | Autologous suspension of keratinocytes, fibroblasts, Langerhans cells and melanocytes | Direct Application to Burns | NA | Approved for marketing in Europe, Canada, China and Australia. (USA-Phase III starting in 2015) |

| Avita Medical | ReGenerCell | Autologous suspension of keratinocytes, fibroblasts, Langerhans cells and melanocytes | For chronic wounds like diabetic foot ulcers and venous leg ulcers | NA | Pilot Trial Launched in 2013, concludes in 2015 |

| Regenicin Inc. | PermaDerm® | Autologous keratinocytes and fibroblasts on absorbable collagen substrate | Treatment for catastrophic burns | FDA assigns PermaDerm® to be a biological/drug (permanent skin replacement) | FDA approved Orphan Status (for therapy that may impact very few individuals) |

| Regenerys | CryoSkin® | Suspension of allogeneic human keratinocytes | Chronic wounds and burns | Can be cryopreserved, and made available as a spray | available upon clinician’s request in the UK |

| Regenerys | MySkin® | The polymer film promotes cell growth and releases the cells upon exposure to the wound. It provides factors that facilitate the migration of the patient's epithelial cells which subsequently close the wound | Autologous keratinocyte for burns and non-healing wounds. Burns | Cultured keratinocytes are delivered on a chemically-defined transfer polymer film. | Phase-III |

| Discontinued Products | |||||

| BioTissue Technologies AG, | BioSeed®-S | Autologous keratinocyte- | Treatment of chronic leg ulcers | NA | No longer part of company portfolio |

| fibrin glue suspension | |||||

| Altrika/Regenerys | Lyphodermj™ | Lysate of cultured human keratinocytes | Treatment of chronic leg ulcers | NA | No longer part of company portfolio |

| Euroderm GmbH | EpiDex™ | Cultured epidermal autograft | Treatment of chronic leg ulcers | NA | Company no longer exists |

| TISSUE tech | autograft system™ | Autologous keratinocytes and fibroblasts grown on Hyaluronic Acid scaffolds | Deep, chronic wounds | NA | Product no longer in company’s portfolio |

| Cell Therapy in Trials | |||||

| Sponsor | Description | Indications | Comments | Phase | |

| Modern Cell and Tissue Technology | Antequera Hill (Keraheal™) | Keraheal™ is a liquid suspension containing mainly non-differentiated preconfluent cells | burns | Keraheal™ is comprised of autologous cultured human epidermal kertinocytes | Phase-III |

| UniversitaireZiekenhuizen Leuven | NA | Prospective Long-term Single Center Cohort Study Assessing Functional Outcome of Urethral Reconstructive Surger | Urethral Strictures | NCT01982136 | NA |

| Burnasyan Federal Medical Biophysical Center | NA | Autologous adipose-derived regenerative cells (ADRC) extracted using Celution 800/CRS System (Cytori Therapeutics Inc) fat harvested from the patient's front abdominal wall. | Urethral Strictures | NCT01889888 | Phase-II |

| Centre HospitalierUniversitaire Vaudois | NA | Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) and Keratinocyte (KC) Suspensions | Acceleration of Wound Healing | Suspension of PRP and KC sprayed onto wound bed with 10% Calcium Chloride | Phase I |

| Stratatech | StrataGraft | Stratified epithelial tissue composed of dermal fibroblasts overlaid with human epidermal keratinocytes | Skin Wound | For patients with 3-49% injury in terms of Body Surface Area | Orphan Status Granted in 2012; |

| Burns, Infection Related Wound, Trauma-related Wound | |||||

| Association of Dutch Burn Centres | NA | Cultured autologous keratinocytes | Burns | NA | Phase III |

| Seoul National University Hospital | NA | Autologous Oral Mucosal Epithelial Sheet | Ocular Surface Reconstruction | NA | Phase II |

Most of the TEMPs undergo non-systemic drug delivery approaches and there is an intimate contact between the TEMPs and the target tissues. These approaches usually have low drug dissipation and restricted drug distribution compared to systemic drug delivery[27]. Hence, the risks of developing systemic adverse events are minimized with topical application of TEMPs. The regulations for these topical applications of TEMPs need to be developed in a similar fashion of tropical generic products. For eg, Integra® DRT (Dermal Regeneration Template) Integra Life sciences was launched in1996; Similarly, Apligraf® of Organogenesis was approved by USFDA in 1998[28,29]. There are no similar TEMPs (like biosimilars) products are available and their product patents are near to expiry. The need has arrived to create special regulatory framework for similar TEMPs. The extensive physio-chemical characteristics of similar TEMPs in comparison to the innovators product should reduce some of the animal testing. Definite framework and recommendations/guidelines to be reformulated based on safety, efficacy and applicability of tissue functions. However, critical safety and efficacy to be demonstrated before entering into clinical trials, besides developing surrogate models for TEMPs. Some of the unrelated testing criteria such as bio-distribution studies for localized TEMPs may not be required.

Regulations for innovative TEMPS

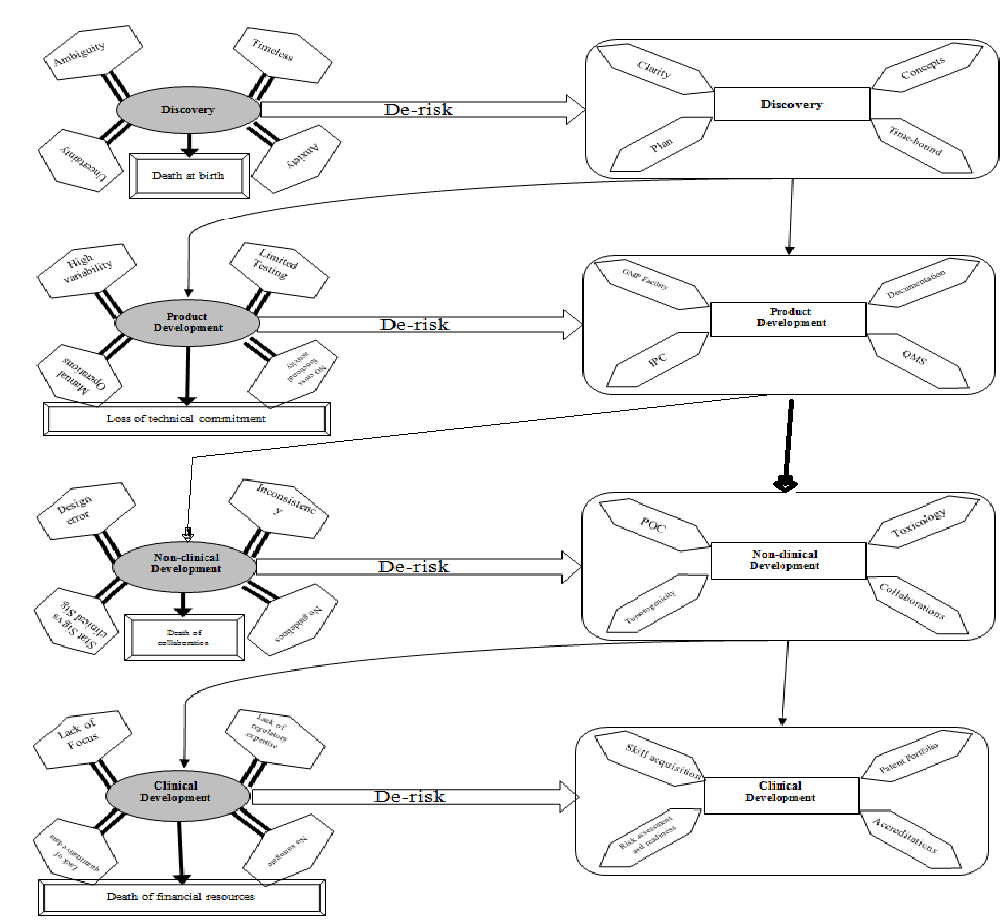

There are several new concepts for creating innovative TEMPs starting from the isolation of cells, inducing tissue with growth factors, small molecules to promote cell growth, survival, migration etc for treating various disease indications. The advanced techniques like perfusion decellularization to generate intact extracellular matrix scaffolds enable the use of patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) technology for organ engineering of rodent kidney[30]. Further, the antimicrobial scaffolds for drug-release strategy and structural biomimetic scaffolds of nanofibrous are some of the promising next generation TEMPs that have improved biocompatibility[31,32]. Moreover, there are several products in development, some are approved by regulators and some are still in development (Table IV) at various levels to meet the market requirements. The transition of innovative TEMPs/medical break through need to cross several valleys of death starting from discovery to product release. Meslin ME et al., highlighted the characteristics and illustrated more than two common “valley of deaths” and the promising strategies to overcome these challenges[33]. On Contrary, the Thompson, S.D (2014) described the real translation of “bench to bedside” need to pass through a barrier of “two valley of death” to get tangible results from biomedical research[34]. Hence, it is even quite challenging for start-up organizations that focus on innovative product development. The (Figure 2) illustrate the roadmap of general challenges that occur during innovative product developments. The early discovery phase was plagued with ambiguity, timelessness, uncertainty and anxiety, and these can be derisked by concepts, time-bound, clarity, and plan. Similarly, the various phases of developments are riddled with scientific, technical, financial and commitment challenges (Figure 2). These inherited risks can be rectified through generation of robust evidences on proof of concept (POC), high quality measurable clinical data, deep and wide of regulatory approaches and strong patent portfolio. Overcoming the scientific challenges and strong data enables the high confidences and attracts unhindered investments. On the other hand, forged enduring collaborations with big and small organization, rich experiences, highly qualified and trained individual creates further value and assets to the organization. Besides, responsive reliable and quick of changes or new projects initiative, pro-activeness are some of the beneficial outcome. These enables the organizations for the creation of unshakeable reputation, mission towards strong vision, de-risking strategies, committed, dedicated manpower, technical and knowledge cluster, accreditations, patent and publications.

Figure 2: General challenges on the critical path to innovative medicinal products. Overview of various risk associated at each stage of development and its risk-free approaches.

Abbreviations:: IPC-In process controls; IMP- Investigational Medicinal Products; POC-Proof of concept; QMS-Quality Management System; GMP-Good manufacturing practices.

Besides, inherited innovation risk, business, financial and organization re-organizations preparedness are some insurmountable developmental stages to move towards optimistic growth opportunity. On the other hand, in-depth analysis and attention is required for innovative TEMPs for framing a conducive environment to test in a scientific, legal and ethical way. The full elucidation of safety, quality, efficacy, biochemical and physiological interaction can begin in pre-clinical in non-human primates of two different species instead of classical small animal in-vivo testing. The positive and negative pre-clinical results are to be published and made available to patients and public. These TEMPs can be tested in various general veterinary medical hospitals with due animal ethics approvals as pre-clinical results and an opportunity to upgrade the veterinary clinical medicine[35]. Pre-clinical studies provides the basic toxicity profiles, enables to identify the active dose levels, adverse events, supports trial eligibility criteria, and enables to identify the critical clinical parameters, risk benefit criteria. Moreover, long term toxicity studies and a tumorgenicity study provide valuable insight in short lived animal’s models. The FDA perspective on pre-clinical assessments of cell products reflects the expectation of agencies[36]. Majority of investigational products were tested on immunodeficient mice as a part of immune rejection assays. The significant technological advancement in animal testing provides greater evidence on safety, potency and probable health risk to patients. Generally, the randomized placebo controlled trials of classical regulatory model cannot be applied for TEMPs. Originators of innovative products are changing their processes due to technological advancement, changes in regulatory requirements, cost-effectiveness and to extend patent life. The complexity of the TEMPs and lack of knowledge and techniques used in the analysis of regenerative products have resulted in delay in regulatory discussion making process. On the other hand, FDA initiatives were taken to identify and address the regulatory knowledge gap like infrastructure requirements, documentation, process maps, cGMP compliances etc., through reviewing sponsor development plan and educating students, academia and industry through TERMIS annual meeting, fellowship program etc. In addition, public workshop was laid down for promoting the understanding of regulatory decision making process[37]. Further, these agencies networking, collaborating, updating, maintaining the scientific rigor, training their staff towards advanced technological concepts and working to ensure safety of public health as topmost priority.

Arnold I Caplan et al., (2014) proposed the progressive regulatory model to establish efficient safety and efficacy of product that will eliminate costly time-consuming traditional phase-II and III trials[38]. On the other hand, international regulatory considerations were formulated to accelerate the promising therapies through clinical trials and subsequent commercialization to patients[39]. Interestingly, the recent overwhelmingly response by U.S. House to streamline the drug approval process regenerate the hope of shorter clinical trial path[40]. Besides, Indian clinical trial execution and regulatory process enables to identify and overcome ethical, regulatory and scientific challenges as a model for rapidly developing countries[41]. Further, India took a step ahead by providing conditional pre-market approval of stempeucel-CLI product after Phase-II[42]. In addition, Vestergaard HT et al., concluded that the classical regulatory approaches were insufficient due to complexity of innovative medicines[43]. The analysis was focused on non-clinical issues and the case-by-case regulatory approach allows sufficient flexibility for the translational clinical transformation opting to their recommendation to minimize the risk.

The streamlining the regulatory approaches in India for biosimilar (similar biologics) or innovative biopharma product business is governed by several government agencies. These includes ICMR, CDSCO, DBT, Genetic engineering approval committee (GEAC), Recombinant DNA advisory committee (RDAC), Review committee on Genetic manipulation (RCGM), Institutional Biosafety committee (IBSC), National centre for Biologic sciences, National control laboratory for biologics[44]. Similarly, there is a pressing need for the evolution of regenerative biopharmaceutical regulatory agencies to follow an analogous approach of biologics. On the other hand, it is necessary to look into the other nation’s regulatory policies that have out-reached the stages of clinical trial approvals, pre-market approval and commercialization in developed countries. For example: the Korean Ministry of Food and Drug safety (MFDS) approved 16 Cell therapy products (CTP). 4 stem CTP, 135 authorized clinical trials provides an impetus pulse of momentum to develop novel CTP and TEP products for serious disease indications[45]>. However, there is no clear regulatory pathway for TEP in Korea and most of the approved therapeutics are of autologous origin. The cell and tissue therapies (CTT) in Malaysia are evolving as evident by few clinical trials (phase-I) and existences of four GMP certified laboratories for various stem cell activities[46]. The pragmatic regulatory oversight and control by three disciplinary approaches.

1. Clinical/medical use of the product – medical practice. 2. Medical device act and 3. National pharmaceutical control bureau (NPCB). The CTT regulations followed the risk based approaches and are categorized as class-I: low risk cellular therapy product and class-II as high risk cellular therapy products. The cell and tissue based products comes under class-II classification. In 2004, the lab scale production of human skin substitute were started in tissue engineering centre, university kebangsaan Malaysia medical centre. The same centre is expected to finish the phase-I clinical trial by end of 2015. The formulating regulatory policy, NPCB stringency of strict regulation and control helped to lay down the quality product, but may cost the time. The CTT products in Singapore follows a risk based tiered approach and are regulated under the medicines Act. A new regulations were proposed to regulate broad spectrum of CTT products under the Health Product Act[47]. The CTT products were classified based on degree of manipulation (substantial or minimal), Intended purpose of usage (homologous or non-homologous) and with combination with drug, device or biologics. Conduct of clinical trial is regulated by Medicines Act and the medicines regulations. The Health Sciences Authority (HSA) is for the assessment of product license and clinical trial certificate (CTC) based on ICH, PICs or any other HSA’s referral standards. The HSA evaluated the Investigational CTT products includes T cells, NK cells, dendritic cells, Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) and MSCs grown on scaffolds and viral and non-viral gene vectors[47].

Currently, the sizable delay time of the new drug approvals is 1.1 year in Japan as indicated by Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), part of Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW)[48-50]. Further, the support and enhancement of The Act on the Safety of Regenerative Medicine (ASRM) were legislated in 2014 to govern the safety aspects of products. On the other hand, amendments to the guidelines accompanying these two act (PDMA and ASRM) speeds up the development of innovative medicines, and strengthen the safety, quality and effective CTT products to Japanese patients. These new regulations accelerated the commercialization of CTT product as evident by TEMCell (JCR Pharmaceuticals) – allogeneic MSCs for GVHD and HeartSheet (Terumo) - autologous skeletal muscle cells for heart failure. These approvals are time-limit based conditional approval without phase-III trials. On contrary, Nature editorial stated it as an unproven system uses patients to pay for clinical trials and enhances the ineffective drugs in circulations. Besides it does not guarantee the Japan’s drug authority about the post-commercialization evaluation of safety and efficacy of the products[51]. Therefore, these new system of fast-track approval of drug should be carefully evaluated, as there is a chance to lose millions of currency for an ineffective treatment. On the other hand, Canadian regulatory agencies attempted for evaluating current polices to identify the gaps and international harmonization initiatives for fast-track conditional marketing approval system[52]. The novel regenerative medicinal products and other novel bio-therapeutics are regulated as advanced medicinal products (AMPs) under Food and Drug Act in Canada. The AMP is regulated under the Cells, Tissues and Organs (CTO) guidelines for transplantation regulations, and are promulgated by Canadian Standards Association. Prochymal was approved under temporary conditional approval process for 4 years till 2016, and there by sponsor need to submit an application to get full market authorization in Canada. Recently (Jan 2016), new legislation by US Congress have taken step to introduce new standards for regenerative medicine that have entitled Advancing Standards in Regenerative Medicine Act. This new bill will enhances to establish Standards coordinating body to develop standards for clinical translation of advanced therapies[53]. The dynamics of regulatory requirements is inevitable and relevant update, revised regulatory sciences of relevant regulatory bodies were constructed as an online regulatory resources for UK and US nations[54]. On the other hand, emerging innovative product across the globe poses the country specific regulations that need to be harmonized for unified consensus guidelines by International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. Overall, various emerging regulatory pathways across different nation are building standards to define the product and its classification system; and most of them follows the risk-based approach. Apart from risk-based approaches, there is a need to develop rationale for regulatory decision-making for evaluating the safety and efficacy of TE/RM technologies. TERMIS-AM industrial committee and TERMIS-Europe in coordination with FDA has made an attempt to develop unified regulation system for TE/RM products[37,55].

Another challenge for clinical transformation and commercialization of innovative therapeutics in India is that the country does not have higher entrepreneurial exploitation to create innovation, biomedical ecosystem in CTT sector, as it makes risk of burning money, time and manpower with no immediate returns. However, the innovative healthcare products and innovation is the prime generator of economic growth that forms prominent contribution for national GDP growth rate and serves the unmet medical needs[56]. Another challenge is dearth of commitment from the clinical community resulting in commercial failure of cell therapy products. Other challenges are cost-effectiveness, efficacy, reimbursement, adequate infrastructure, maintaining critical quality attributes, and regulation for innovative companies[57]. Hence, the unaddressed or not upgraded regulation in many nations may negatively affect the society by exposing patients to unproven and unethical cell or tissue based therapies[58]. Many Indian clinics are making false claims and fake declaration of approval of concern authority for their hightech stem cell activities[59]. This may be due to ignorance’s of medical practitioner, clinician, statutory gap; lack of proper governances with societal hype of excitation on stem cells may drag a step back of our economy, while keeping the patient life under risk. Hence, there is a need for three dimensional growth in this sector to raise the risk entrepreneur, knowledge cluster as well as innovative regulatory sciences development and regulatory educational programs by government agencies, industrial-academic collaborative programmes and private partnership.

Conclusion

The new class of TEMPs provides revolutionary innovative therapeutic options for people with life-threatening disease. On the other hand, any delay in clinical transition of already known technologies or similar technologies can alleviate human sufferings. Besides, these novel TEMPs require special attention to make specific harmonised regulations that should enhance constructive development and progression of research findings into viable clinical options. Recent new approaches by EMA on risk-based assessment for conditional licensing, adaptive licensing and accelerated regulatory pathway in Japan provides confidences and hope of regulatory developments for new therapeutics. Patient safety to be given the top most priority, while considering the lessons learned from past success, failures and roadblocks in clinical translations. The innovative organization/sponsor requires direct feedback and recommendation from regulatory agencies, ethics committees, scientific committees and clinicians for successful clinical translation of TEMPs at regular intervals. Major stake holders in developing TEMPS are academic groups, innovative organizations or sponsors, and regulatory agencies supported by inputs from visionary clinicians and investors. These are to be nurtured for the successful clinical translation of TEMPs.

Acknowledgment

SRTE is fully supported by Sri Sringeri Sharada peetam. The author wishes to thank to Dr. Gautham Nadig for his critical review and valuable suggestions.

Conflict of Interest:

The author discloses no conflict of Interest.

References

- 1. Liddell, K., Wallace, S. Emerging Regulatory Issues for Human Stem Cell Medicine1. (2005) Genomics society and Policy 1(1): 54.

- 2. Pirnay, J.P., Vanderkelen, A., De Vos, D., et al. Business oriented EU human cell and tissue product legislation will adversely impact Member States' health care systems. (2013) Cell Tissue Bank 14(4): 525-560.

- 3. Horn-Ranney, E.L., Khoshakhlagh, P., Kaiga, J.W., et al. Light-reactive dextran gels with immobilized guidance cues for directed neurite growth in 3D models. (2014) Biomater Sci 2(10): 1450-1459.

- 4. Flory, E., Reinhardt, J. European regulatory tools for advanced therapy medicinal products. (2013) Transfus Med Hemothe 40(6): 409-412.

- 5. Buljovcic, Z. European Marketing Authorisation: a long process. Experiences of small biotech companies with the ATMP regulation. (2011) Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 54(7): 831-838.

- 6. Nath, N., Saraswat, S.K., Jain, S., et al. Inhibition of proliferation and migration of stricture fibroblasts by epithelial cell-conditioned media. (2015) Indian J Urol 31(2): 111-115.

- 7. German, P.G., Schuhmacher, A., Harrison, J., et al. How to create innovation by building the translation bridge from basic research into medicinal drugs: an industrial perspective. (2013) Hum Genomics 7: 5.

- 8. Van Wilder, P. Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products and Exemptions to the Regulation 1394/2007: How Confident Can We be? An Exploratory Analysis. (2012) Front Pharmacol 3: 12.

- 9. FDA-U.S Food and Drug Administration, Drug Approval Process.

- 10. DiMasi, J.A., Hansen, R.W., Grabowski, H.G. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. (2003) J Health Econ 22(2): 151-185.

- 11. Davis, J.R, Nolan, V.P, Woodcock, J., et al. Assuring Data Quality and Validity in Clinical Trials for Regulatory Decision Making. (1999) Workshop Report Washington (DC).

- 12. Taylor, D.A., Caplan, A.L., Macchiarini, P. Ethics of bioengineering organs and tissues. (2014) Expert Opin Biol Ther 14(7): 879-882.

- 13. Boennelycke, M., Gras, S., Lose, G. Tissue engineering as a potential alternative or adjunct to surgical reconstruction in treating pelvic organ prolapse. (2013) Int Urogynecol J 24(5): 741-747.

- 14. Reflection paper on classification of advanced therapy medicinal products.

- 15. European Parliament and Council: Regulation (EC) No 1394/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 November 2007 on advanced therapy medicinal products and amending Directive 2001/83/EC and Regulation (EC) No 726/2004. (2007) Official Journal of the European Union L324/121-137.

- 16. Maciulaitis, R., D'Apote, L., Buchanan, A., et al. Clinical development of advanced therapy medicinal products in Europe: evidence that regulators must be proactive. (2012) Mol Ther 20(3): 479-482.

- 17. Pearce, K.F., Hildebrandt, M., Greinix, H., et al. Regulation of advanced therapy medicinal products in Europe and the role of academia. (2014) Cytotherapy 16(3): 289-297.

- 18. Katari, R., Peloso, A., Orlando, G. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: semantic considerations for an evolving paradigm. (2014) Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2: 57.

- 19. Lee, M.H., Arcidiacono, J.A., Bilek, A.M., et al. Considerations for tissue-engineered and regenerative medicine product development prior to clinical trials in the United States. (2010) Tissue Eng Part B Rev 16(1): 41-54.

- 20. Gottipamula, S., Muttigi, M.S., Kolkundkar, U., et al. Serum-free media for the production of human mesenchymal stromal cells: a review. (2013) Cell Prolif 46(6): 608-627.

- 21. Gottipamula, S., Muttigi, M.S., Chaansa, S., et al. Large-scale expansion of pre-isolated bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells in serum-free conditions. (2013) J Tissue Eng Regen Med 10(2):108-19.

- 22. Church, D., Elsayed, S., Reid, O., et al. Burn wound infections. (2006) Clin Microbiol Rev 19(2): 403-434.

- 23. Williams, D.F. Reconstructing the Body: Costs, Prices and Risks. (2003) Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance Issues and Practice 28(2): 331-338.

- 24. Lionberger, R.A. FDA critical path initiatives: opportunities for generic drug development. (2008) The AAPS journal 10(1): 103-109.

- 25. Reinke, T. Encouraging guidance released for biosimilar manufacturers. (2014) Manag Care 23(8): 10-13.

- 26. Directorate general of Health Services Central Drugs Standard Control Organization Biological Division.

- 27. Surber, C., Smith, E.W. The mystical effects of dermatological vehicles. (2005) Dermatology 210(2): 157-168.

- 28. Kirsner, R.S. The use of Apligraf in acute wounds. (1998) J Dermatol 25(12): 805-811.

- 29. Zhang, Z., Michniak-Kohn, B.B. Tissue engineered human skin equivalents. (2012) Pharmaceutics 4(1): 26-41

- 30. Caralt, M., Uzarski, J., Iacob, S., et al. Optimization and Critical Evaluation of Decellularization Strategies to Develop Renal Extracellular Matrix Scaffolds as Biological Templates for Organ Engineering and Transplantation. (2015) Am J Transplant 15(1): 64-75.

- 31. Tiller, J.C., Sprich, C., Hartmann, L. Amphiphilic conetworks as regenerative controlled releasing antimicrobial coatings. (2005) J Control Release 103(2): 355-367.

- 32. Guo, B., Lei, B., Li, P., et al. Functionalized scaffolds to enhance tissue regeneration. (2015) Regen Biomater 2(1):47-57.

- 33. Meslin, E.M,, Blasimme, A., Cambon-Thomsen, A. Mapping the translational science policy 'valley of death'. (2013) Clin Transl Med 2(1): 14.

- 34. Thompson, S.D. Scientific innovation's two Valleys of Death: how blood and tissue banks can help to bridge the gap. (2014) Stem Cells Dev 23(1): 68-72.

- 35. Brehm, W., Burk, J., Delling, U., et al. Stem cell-based tissue engineering in veterinary orthopaedics. (2012) Cell Tissue Res 347(3): 677-688.

- 36. Bailey, A.M., Mendicino, M., Au, P. An FDA perspective on preclinical development of cell-based regenerative medicine products. (2014) Nat Biotechnol 32(8): 721-723.

- 37. Bertram, T.A., Johnson, P.C., Tawi, B., et al. Enhancing tissue engineering/regenerative medical product commercialization: the role of science in regulatory decision making for tissue engineering/regenerative medicine product development. (2013) Tissue Eng Part A 19(21-22):2313.

- 38. Caplan, A.I., West, M.D. Progressive approval: a proposal for a new regulatory pathway for regenerative medicine. (2014) Stem Cells Transl Med 3(5):560-563.

- 39. Feigal, E.G., Tsokas, K., Viswanathan, S., et al. Proceedings: International Regulatory Considerations on Development Pathways for Cell Therapies. (2014) Stem Cells Transl Med 3(8): 879-887.

- 40. Jaffe, S. 21st Century Cures Act progresses through US Congress. (2015) Lancet 385(9983): 2137-2138.

- 41. Viswanathan, S., Rao, M., Keating, A., et al. Overcoming challenges to initiating cell therapy clinical trials in rapidly developing countries: India as a model. (2013) Stem Cells Transl Med 2(8): 607.

- 42. Meeting for clarification of minutes of meeting of seventh cbbt dec, held on 3rd feb, 2015 at ICMR, New Delhi.

- 43. Vestergaard, H.T., D'Apote, L., Schneider, C.K., et al. The evolution of nonclinical regulatory science: advanced therapy medicinal products as a paradigm. (2013) Mol Ther 21(9): 1644-1648.

- 44. Nellore, R. Regulatory considerations for biosimilars. (2010) Perspect Clin Res 1(1): 11-14.

- 45. Lim, J.O. Regulation Policy on Cell- and Tissue-Based Therapy Products in Korea. (2015) Tissue Eng Part A 21(23-24): 2791-2796.

- 46. Bt Hj Idrus, R., Abas, A., Ab Rahim, F., et al. Clinical Translation of Cell Therapy, Tissue Engineering, and Regenerative Medicine Product in Malaysia and Its Regulatory Policy. (2015) Tissue Eng Part A 21(23-24): 2812-2816.

- 47. Kellathur, S.N. Regulation of Cell- and Tissue-Based Therapeutic Products in Singapore. (2015) Tissue Eng Part A 21(23-24): 2802-2805.

- 48. Hayakawa, T., Aoi, T., Bravery, C., et al.. Report of the international conference on regulatory endeavors towards the sound development of human cell therapy products. (2015) Biologicals 43(5): 283-297.

- 49. Konomi, K., et al. New Japanese initiatives on stem cell therapies. (2015) Cell Stem Cell 16(4): 350-352.

- 50. Maeda, D., Yamaguchi, T., Ishizuka, T., et al. Regulatory Frameworks for Gene and Cell Therapies in Japan. (2015) Adv Exp Med Biol 871: 147-162.

- 51. Stem the tide. (2015) Nature 528(7581): 163-164.

- 52. Viswanathan, S., Bubela, T. Current practices and reform proposals for the regulation of advanced medicinal products in Canada. (2015) Regen Med 10(5): 647-663.

- 53. Congress.gov (Internet). Advancing standards in Regenerative Medicine Act (S.2443) – 114th Congress.

- 54. Culme-Seymour, E. J., Davies, J.L., Hitchcock, J., et al. Cell Therapy Regulatory Toolkit: an online regulatory resource. (2015) Regen Med 10(5): 531-534.

- 55. Bertram, T.A., Johnson, P.C., Tawil, B.J., et al. Enhancing Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine Product Commercialization: The Role of Science in Regulatory Decision-Making for the TE/RM Product Development. (2015) Tissue Eng Part A 21(19-20): 2476-2479

- 56. Bayon, Y., Vertès, A.A., Ronfard, V., et al. Turning Regenerative Medicine Breakthrough Ideas and Innovations into Commercial Products. (2015) Tissue Eng Part B Rev 21(6): 560-571.

- 57. Davies, B. M., et al. Quantitative assessment of barriers to the clinical development and adoption of cellular therapies: A pilot study. (2014) J Tissue Eng 5: 2041731414551764.

- 58. Dominici, M., Nichols, K., Srivastava, A., et al. Positioning a Scientific Community on Unproven Cellular Therapies: The 2015 International Society for Cellular Therapy Perspective. (2015) Cytotherapy 17(12): 1663-1666.

- 59. Tiwari, S.S., Raman, S. Governing stem cell therapy in India: regulatory vacuum or jurisdictional ambiguity? (2014) New Genet Soc 33(4): 413-433.