Comparative Efficiency of Sulfonylurea and/or Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 inhibitor in Basal-Supported Oral Therapy in Japanese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (JDDM39)

Koichi Hirao2, Shin-ichiro Sirabe2, Hajime Maeda2, Ritsuko Yamamoto2, Atushi Kumakura3, Namiko Samoto2, Atsunori Kashiwagi4, Japan Diabetes Clinical Data Management Study Group

Corresponding Author

Keiko Arai, M.D., Ph.D. Arai Clinic, 1-19, Moegino, Aoba-ku, Yokohama 227-0044, Japan. Tel: +81-45-532-8820, Fax: +81-45-532-8821; E-mail: arai-cl@n04.itscom.net

Citation

Arai, K., et al. Comparative Efficiency of Sulfonylurea and/or Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitor in Basal-Supported Oral Therapy in Japanese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (JDDM 39). (2015) J Diab Obes 2(2): 79- 84.

Copy rights

©2015 Arai, K. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Basal Oral supported Therapy (BOT); Sulfonylurea; Dipeptidyl peptidase- 4 inhibitor (DPP-4i); Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM); HbA1c

Abstract

Basal-supported Oral Therapy (BOT), comprising treatment with oral antidiabetic drugs and once-daily injections of a long-acting insulin analog, is a convenient regimen. However, it sometimes fails to achieve satisfactory glycemic control because of uncontrolled hyperglycemia in the postprandial period. The aim of the present retrospective cohort study was to assess the efficiency of a sulfonylurea (SU) and/or a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor (DPP-4i) on glycemic control in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) who were receiving BOT. The 243 T2DM patients who started long-acting insulin added onto an SU and/or DPP-4i, with or without metformin, were followed-up for 6 months. Mean HbA1c levels in the SU, DPP-4i, and SU + DPP-4i groups decreased steadily from baseline by approximately 1% over the 6-month followed-up period. After 6 months, 57.4%, 51.6%, and 62.2% of patients in the SU, DPP-4i, and SU + DPP-4i groups, respectively, had continued on the same therapeutic regimen, and 15.2%, 18.5%, and 16.5% of patients, respectively, had achieved HbA1c levels <7.0%. The efficiency of BOT with SU, DPP-4i, and SU + DPP-4i was limited, but some patients (i.e. those with a lower body mass index and HbA1c) may benefit from these BOT regimens.

Introduction

Insulin therapy is often required, even in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), to achieve satisfactory glycemic control[1]. Intensified insulin therapy using a basal–bolus regimen has been reported to provide better glycemic control than convenience-oriented insulin therapy[2,3]. However, multiple daily injection regimens may not be desirable, especially for patients with a highly active lifestyle. Consequently, it is becoming increasingly necessary to select therapeutic regimens that not only effectively maintain glycemic control, but also allow diabetic patients to pursue many daily activities. In this regard, basal-supported oral therapy (BOT), which is combination treatment with oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs) and once-daily injections of a long-acting insulin analog, may prove to be a convenient treatment regimen.

In BOT, long-acting insulin analog supplies basal insulin, resulting in improvements in fasting plasma glucose (FPG), but not reductions in postprandial plasma plucose (PPG). Some patients on BOT fail to achieve satisfactory glycemic control because of uncontrolled hyperglycemia during the postprandial period, even though preprandial blood glucose levels are low enough[4,5]. Delayed and inadequate postprandial insulin secretion is a particular problem for Japanese T2DM patients[6]. In such cases, the combination of an insulin-secreting OAD, such as a sulfonylurea (SU) and/or a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor (DPP-4i), in combination with long-acting insulin may provide a solution to this problem.

A recent (2011) study of OAD prescribing trends in Japan reported that SUs were most commonly used in combination therapy, followed by biguanides and DPP-4i[7]. Indeed, the efficiency of the long-acting insulin plus SU regimen on blood glucose control has been demonstrated in Japanese T2DM patients[8-10]. However, use of SU has some concerns, such as hypoglycemia, body-weight gain and deteriorating beta cell function by long-time use. As another type of OAD, DPP-4i (which promote insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner) has recently become available and their efficiency for improving glycemic control has been demonstrated[11]. The glucose-lowering effect of DPP-4i is dependent on blood glucose concentrations and is due to enhanced insulin secretion and inhibition of glucagon secretion[12,13]. Combination therapy with DPP-4i and insulin has also been shown to be effective in patients with T2DM[14,15].

However, it in not fully understood the efficiency of insulin-secreting OADs such as SU and/or DPP-4i as a part of BOT. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the efficiency of SU and/or DPP-4i on glycemic control in Japanese T2DM patients receiving BOT retrospectively in real clinical practice setting.

Methods

Ethical Considerations

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Japan Diabetes Clinical Data Management Study Group (JDDM), which also includes outside members, such as lawyers and ethics experts. The JDDM operates as an aggregate organization under the supervision of the central analytical facility and an ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from all patients at each participating institute, in accordance with the Guidelines for Epidemiological Study of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.

Subjects

The present study was a retrospective cohort study. Patients were recruited from 47 clinics and hospitals that belonged to the JDDM. The study was performed on 243 patients with T2DM who started a long-acting insulin added onto an SU and/or DPP-4i, with or without metformin, at each participating institute between March 2011 and July 2013 and who were followed-up for 6 months. Patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) were excluded from the study. The type of diabetes was determined on the basis of the criteria of the Japan Diabetes Society (JDS) for the diagnosis of diabetes[16], which are almost identical to those of the World Health Organization[17]. Briefly, patients who were permanently insulinopenic and ketosis prone (idiopathic T1DM) or those who were positive for autoimmune destruction markers, such as glutamic acid decarboxylase (immune-mediated T1DM) were diagnosed as having T1DM. Patients included in the study were divided three groups on the basis of the OAD used: (1) SU, with or without metformin (n = 101); (2) DPP-4i, with or without metformin (n = 31), and (3) SU + DPP-4i, with or without metformin (n = 111). The clinical data for all patients were standardized and saved using CoDiC software, as described previously[18]. Data were collected at the central analytical facility, where the information was treated anonymously.

Measurement and Standardization of Data

Data regarding age, sex, height, body weight, duration of diabetes, combination with or without metformin, and daily dose of insulin were collected for each patient at the time of insulin initiation as baseline characteristics. Weight and height were measured using standard techniques and equipment, and were used to calculate Body Mass Index (BMI). HbA1c was measured by HPLC at baseline and then again 3 and 6 months after insulin initiation. FPG levels were measured by the glucose oxidase method before insulin initiation as baseline values.

Statistical Analysis

Unless stated otherwise, all data were analyzed in the intention-to treat population, comprising all patients, including those who did not continue the initial regimen up to the 6-month follow-up point. The HbA1c levels in each group at baseline and at 3 and 6 months were analyzed by repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) following multiple comparisons by Bonferroni’s method.

To compare data among the three groups, ANOVA following multiple comparisons by Bonferroni’s method was used for continuous variables (age, duration of T2DM, BMI, HbA1c, daily insulin dose, and FPG), whereas the Chi-squared test was used for categorical variables (the proportion of men to women, combination with or without metformin, rate of patients continuing on the same therapeutic regimen, and success rate for achieving target HbA1c levels < 7.0%). Variables are presented as the mean ± SD.

To compare baseline characteristics of patients with HbA1c levels < 7.0% and ≥ 7.0% after 6 months treatment in each group, Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables (age, duration of T2DM, BMI, HbA1c, daily insulin dose, and FPG), whereas the Chi-squared test was used for categorical variables (the proportion of men to women, combination with or without metformin).

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 13.0J for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Two-sided P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the three treatment groups. There were no significant differences in any factors at baseline among the three groups.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of the study subjects

| SU | DPP-4i | SU + DPP-4i | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients | 101 | 31 | 111 |

| Age (years) | 60.3 ± 13.8 | 61.6 ± 12.0 | 64.3 ± 12.3 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 11.3 ± 7.8 | 11.5 ± 7.1 | 12.3 ± 8.5 |

| No. men/women | 64/37 | 22/9 | 71/40 |

| Body mass index (kg/m²) | 24.7 ± 4.2 | 25.6 ± 5.2 | 25.0 ± 4.5 |

| Baseline HbA1c (%) | 9.3±1.6 | 8.9±1.5 | 9.2±1.4 |

| No. using metformin (%) | 64 (63.4%) | 13 (42.9%) | 63 (56.5%) |

| Dose of basal insulin (U/day) | 7.7±4.6 | 7.9±4.3 | 6.9±5.1 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 194 ± 62 | 194 ± 42 | 214 ± 92 |

Unless indicated otherwise, data are given as the mean ± SD. SU, sulfonylurea; DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor.

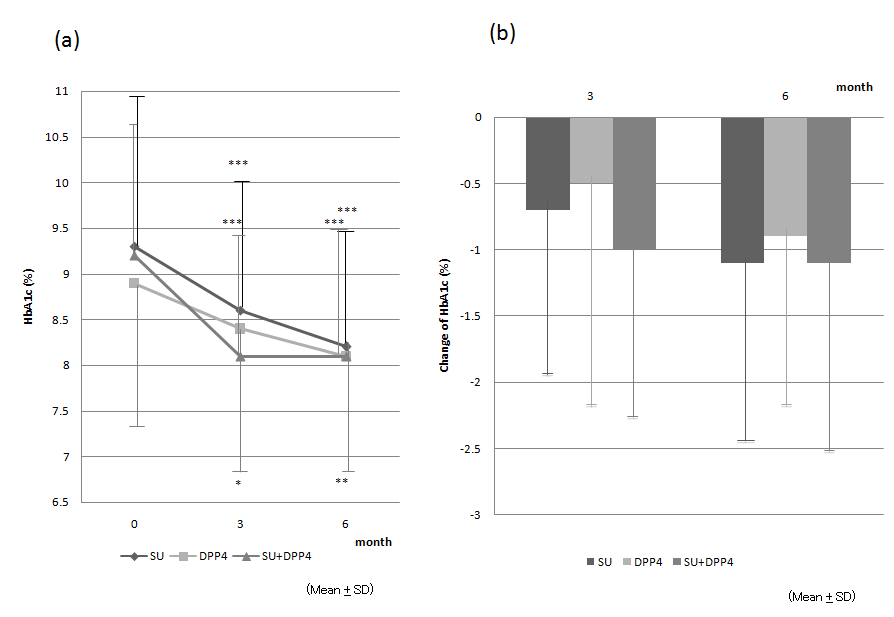

Time-course and change in HbA1c levels Mean HbA1c levels in all three groups decreased steadily, being approximately 1% lower after 6 months treatment compared with baseline (Fig. 1a; Table 2 (a)). Mean HbA1c levels at the 3- and 6-month time points were significantly lower than baseline in all three groups, with no significant differences among the three groups (Fig. 1a; Table 2 (a)). In the subjects without metformin, mean HbA1c levels at the 6-month time points in SU group and SU + DPP4i group were significantly lower than baseline, while there was not different in DPP4i group (Table 2(b)). Furthermore, the changes in HbA1c levels at 3 and 6 months from the baseline did not differ significantly among three groups in both whole subjects and those without metformin (Fig. 1b; Table 2 (a), (b)).

Table 2a: Changes in HbA1c, body mass index, and dosage of basal insulin 3 and 6 months after the addition of basal insulin

| SU | DPP-4i | SU + DPP-4i | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 months | 3 months | 6 months | 0 months | 3 months | 6 months | 0 months | 3 months | 6 months | |

| No. patients | 101 | 73 | 58 | 31 | 23 | 16 | 111 | 83 | 69 |

| No. continuing treatment | |||||||||

| regimen (%) | 100.0 | 72.3 | 57.4 | 100.0 | 74.2 | 51.6 | 100.0 | 74.8 | 62.2 |

| No. (%) using metformin | 64 (63.4%) | 33 (54.7) | 35 (60.3) | 13 (41.9) | 11 (47.8) | 9 (50.0) | 63 (56.8) | 41 (49.4) | 33 (47.8) |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 24.7 ± 4.2 | 24.8 ± 4.0 | 25.0 ± 3.9 | 25.6 ± 5.2 | 25.7 ± 4.5 | 26.1 ± 4.7 | 25.0 ± 4.5 | 25.2 ± 4.6 | 25.2 ± 4.6 |

| ΔBMI from baseline (kg/m²) | 0.0 ± 0.8 | 0.2 ± 1.0 | 0.1±0.8 | 0.3 ± 1.0 | 0.2 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.9 | |||

| HbA1c (%) | 9.3 ± 1.6 | 8.6 ± 1.4 *** | 8.2 ± 1.3*** | 8.9 ± 1.5 | 8.4 ± 1.6* | 8.1 ± 1.3** | 9.2 ± 1.4 | 8.1 ± 1.2*** | 8.1 ± 1.3*** |

| ΔHbA1c from baseline (%) | –0.7 ± 1.3 | –1.1 ± 1.4 | –0.5 ± 1.7 | –0.9 ± 1.3 | –1.0 ± 1.3 | –1.1 ± 1.5 | |||

| % Patients with HbA1c < 7.0% | 3.0 | 11.5 | 15.2 | 9.7 | 17.2 | 18.5 | 2.7 | 11 | 16.5 |

| Dose basal insulin (U/day) | 7.7 ± 4.6 | 12.0 ± 6.8*** | 13.3 ± 6.6*** | 7.9 ± 4.3 | 11.0 ± 5.9* | 12.3 ± 6.5** | 6.9 ± 5.1 | 9.7 ± 5.6†*** | 10.5 ± 5.7†*** |

| ΔInsulin dosage from baseline | |||||||||

| (U/day) | 4.2 ± 4.6 | 5.8 ± 6.1 | 2.6 ± 3.4 | 3.7 ± 3.5 | 3.1 ± 4.4 | 4.3 ± 4.9 | |||

Unless indicated otherwise, data are given as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with baseline in each group; †P < 0.05 compared with sulfonylurea (SU) alone.

DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; BMI, body mass index.

Table 2b: Changes in HbA1c, body mass index, and dosage of basal insulin 3 and 6 months after the addition of obasal insulin without metformin

| SU | DPP-4i | SU + DPP-4i | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 months | 3 months | 6 months | 0 months | 3 months | 6 months | 0 months | 3 months | 6 months | |

| No. patients | 37 | 23 | 18 | 18 | 11 | 7 | 48 | 32 | 28 |

| No. continuing treatment | |||||||||

| regimen (%) | 100.0 | 62.2 | 48.6 | 100.0 | 61.1 | 38.9 | 100.0 | 66.7 | 58.3 |

| No. (%) using metformin | 0 (0%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 22.7 ± 3.3 | 22.9 ± 3.1 | 23.0 ± 3.1 | 23.8 ± 4.7 | 24.2 ± 4.4 | 24.5 ± 4.5 | 23.8 ± 3.6 | 24.0 ± 3.6 | 24.2 ± 3.5 |

| ΔBMI from baseline (kg/m²) | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.2 ± 0.9 | 0.2 ± 1.2 | 0.0 ± 0.9 | 0.2 ± 0.9 | |||

| HbA1c (%) | 9.2 ± 1.6 | 8.4 ± 1.3 *** | 7.8 ± 1.0*** | 8.6 ± 1.5 | 8.5 ± 1.9 | 8.3 ± 1.6 | 9.0 ± 1.2 | 8.2 ± 1.3** | 8.1 ± 1.3*** |

| ΔHbA1c from baseline (%) | –0.7 ± 1.1 | –1.2 ± 1.4 | 0.0 ± 1.4 | –0.4 ± 0.9 | –0.8 ± 1.3 | –0.8 ± 1.3 | |||

| % Patients with HbA1c < 7.0% | 2.7 | 8.8 | 16.1 | 16.7 | 17.6 | 20.0 | 2.1 | 11.4 | 16.7 |

| Dose basal insulin (U/day) | 7.4 ± 3.7 | 12.3 ± 5.2*** | 14.1 ± 6.2*** | 7.3 ± 2.5 | 9.7 ± 3.8 | 11.0 ± 4.2 | 6.9 ± 4.6 | 10.0 ± 7.0NS*** | 11.3 ± 6.8NS*** |

| ΔInsulin dosage from baseline | |||||||||

| (U/day) | 4.9 ± 4.2 | 6.9 ± 5.2 | 1.9 ± 3.2 | 2.8 ± 3.2 | 3.2 ± 4.9 | 4.5 ± 4.8 | |||

Unless indicated otherwise, data are given as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with baseline in each group. ; NSP < 0.1 compared with sulfonylurea (SU) alone.

DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; BMI, body mass index.

Figure 1: (a) Mean (± SD) HbA1c levels in patients who were receiving a sulfonylurea (SU; ●), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor (DPP-4i; ■), or an SU + DPP-4i (▲) in addition to a long-acting insulin. HbA1c levels at 3 and 6 months were significantly lower than baseline in all groups. (b) Mean (± SD) change in HbA1c levels from baseline at 3 and 6 months in the SU, DPP-4i, and SU + DPP-4i groups. HbA1c decreased by approximately 1.0% at 6 months. There were no significant differences among the three groups.

Therapeutic Regimen, BMI, and Insulin Dose

At the 6-month time point, 57.4%, 51.6%, and 62.2% of patients in the SU, DPP-4i, and SU +DPP-4i groups, respectively, had continued on the same therapeutic regimen. The percentage of patients continuing with the same regimen did not differ significantly among the three groups (Table 2 (a)). The reasons for discontinuation of a particular treatment regimen are summarized in Table 3. Some patients stopped the OAD or insulin, whereas a considerable number of patients added or changed OADs and rapid-acting insulin (Table 3).

Table 3: Reason for discontinuation

| SU | DPP-4i | SU + DPP-4i | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change OAD | 7 (6.9%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (9.0%) |

| Add OAD | 7 (6.9%) | 3 (9.7%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Add rapid-acting insulin or biphasic insulin | 12 (11.9%) | 3 (9.7%) | 16 (14.4%) |

| Change insulin to GLP-1 | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Stop OAD | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (3.2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Stop insulin | 3 (3.0%) | 2 (6.5%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Did not follow-up | 12 (11.9%) | 6 (19.4%) | 11 (9.9%) |

Data are given as n (%).

OAD, oral antidiabetic drug; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; SU, sulfonylurea; DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor

There was no significant change in BMI over the 6-month period in any of the three groups in both whole subjects and those without metformin (Table 2 (a), (b)). The dosage of basal insulin was higher in all three groups at 3 and 6 months compared with baseline (Table 2 (a)). In the subjects without metformin, it was higher in SU and SU plus DPP4i group at 3 and 6 months compared with baseline, while there was not significant difference in DPP4i group (Table 2 (b)). At the 3-and 6-month time point, the dose of insulin in the SU + DPP-4i group was significantly lower in whole subjects and lower tendency in those without metformin than that in the SU group (Table 2 (a), (b)).

Differences in baseline characteristics of patients with HbA1c levels < 7.0% and ≥ 7.0% at 6 months

At the 6-month time point, 15.2%, 18.5%, and 16.5% of patients in the SU, DPP-4i, and SU + DPP-4i groups, respectively, achieved HbA1c levels < 7.0% (Table 2 (a)). There was no significant difference in the percentage of patients achieving satisfactory glycemic control among the three groups. In all groups, the BMI at baseline was lower for patients achieving HbA1c levels < 7.0% than in those with HbA1c levels ≥ 7.0% (Table 4). In addition, changes in the insulin dose were smaller and HbA1c levels were higher in patients in the SU and SU + DPP-4i groups achieving HbA1c levels < 7.0% than in those with HbA1c levels ≥ 7.0% (Table 4).

Table 4: Baseline characteristics of subjects with HbA1c < 7.0% and ≥ 7.0%

| SU | DPP-4i | SU + DPP-4i | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c < 7.0% | HbA1c ≥ 7.0% | HbA1c < 7.0% | HbA1c ≥7.0% | HbA1c < 7.0% | HbA1c ≥7.0% | |

| No. patients | 14 | 78 | 5 | 22 | 16 | 81 |

| Age (years) | 63.8 ± 16.2 | 58.9 ± 12.9 | 61.5 ± 11.2 | 62.6 ± 12.6 | 68.4 ± 11.6 | 63.3 ± 12.3 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 14.4 ± 8.7 | 11.1 ± 7.8 | 8.5 ± 6.0 | 12.5 ± 7.2 | 11.2 ± 6.5 | 12.7 ± 8.6 |

| No. men/women | 9/5 | 47/31 | 4/1 | 14/8 | 9/7 | 51/29 |

| BMI at baseline (kg/m²) | 22.6 ± 3.7 | 25.4 ± 4.2* | 21.2± 1.2 | 26.8 ± 5.1* | 22.2± 3.8 | 25.4 ± 4.6* |

| ΔBMI from baseline (kg/m²) | 0.6 ± 1.3 | 0.1 ± 1.0NS | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 0.2 ± 1.1 | 0.3 ± 1.4 | 0.3 ± 1.8 |

| Baseline HbA1c (%) | 8.5± 1.3 | 9.4± 1.5* | 8.0 ± 2.3 | 9.1± 1.3 | 8.5 ± 1.0 | 9.2 ± 1.4NS |

| ΔHbA1c from baseline (%) | –1.8± 1.2 | –1.0 ± 1.4* | –1.6 ± 2.4 | –0.7 ± 1.0 | –1.8 ± 1.1 | –1.0 ± 1.5* |

| % Using metformin | 64.3 | 66.7 | 40 | 45.5 | 56.3 | 56.8 |

| Dose of basal insulin at baseline (U/day) | 7.3 ± 3.6 | 7.8 ± 5.0 | 8.8 ± 3.0 | 7.6 ± 4.9 | 6.8 ± 4.1 | 6.5 ± 4.0 |

| ΔInsulin dosage from baseline (U/day) | 2.1 ± 2.6 | 6.4 ± 6.3* | 7.0 ± 3.6 | 3.1 ± 3.2 | 1.3 ± 4.7 | 5.1± 4.6** |

| FPG at baseline (mg/dL) | 154.2 ± 51.0 | 193.3 ± 62.4 | 149.5 ± 24.8 | 196.0 ± 31.0 | 185.9 ± 60.1 | 208.8 ± 82.2 |

Unless indicated otherwise, data are given as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with HbA1c < 7.0%.

NSP < 0.1; DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; BMI, body mass index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose

Discussion

Regardless of the type of OAD used in combination with basal insulin, mean HbA1c levels had decreased approximately 1% at the 6-month time point compared with baseline. This suggests that BOT may be useful in at least some T2DM patients. Appropriate initiation of insulin may help T2DM patients to achieve long-term satisfactory glycemic control and so prevent the development of complications[1]. However, sometimes both physicians and patients are reluctant to start insulin. Some of the barriers to insulin initiation in patients may include fear of self-injection, hypoglycemia, and weight gain. In contrast, physicians may have concerns regarding patient adherence to the insulin treatment regimen and sometimes they feel they do not have the time to provide adequate diabetes education to their patients[19,20]. Thus, BOT may be a viable alternative, because this regimen requires only once-daily insulin injections and the risk of hypoglycemia is less than that associated with intensified insulin therapy requiring multiple injections[21,22].

Conversely, only half the patients in the present study had continued with the initial treatment regimen and only 15% had achieved satisfactory glycemic control at the 6-month time point. This suggests that the efficiency of BOT may be limited. One of the reasons for this limited efficacy may be uncontrolled hyperglycemia during the postprandial period. The insulin secretion response to glimepiride was improved when it was used in combination with insulin glargine in Japanese T2DM patients[8-10]. This suggests that an SU as part of BOT may improve PPG. The addition of sitagliptin to a regimen consisting of a stable dose of insulin, with or without metformin, resulted in improved glycemic control in FPG and PPG compared with placebo[14]. Add-on sitagliptin therapy in Japanese T2DM patients on insulin alone or insulin combined with other oral agents improved PPG, probably as a result of both sitagliptin-induced glucose-dependent increases in insulin secretion and glucagon suppression[15]. These studies suggest that either an SU or DPP-4i as part of BOT may improve PPG. However, these studies did not directly compare the glucose-lowering effects of an SU and DPP-4i. Unfortunately from our study, it could not be stated the superiority of either an SU or DPP-4i in improving PPG, with no significant differences in HbA1c levels at 3 and 6 months between the two groups. The number of patients in the DPP-4i group was smaller than that in the SU group. This is one of the limitations of the present study. In addition, we did not have enough data about FPG, PPG, c-peptide and hypoglycemia, because this study was real clinical practice setting and retrospective study. This is also one of the limitations of this study.

Combination with metformin may exert additive effects on the SU and/or DPP4i in BOT. From the analysis of the subjects without metformin, the result in change of HbA1c levels in DPP4i group was different from that of whole subjects. This may depend on the very small number of the subjects without metformin and the limitation of statistics. While other results in the patients without metformin has same tendency to those of whole subjects. Further randomized prospective study is necessary to answer the question whether SU or DPP-4i is more effective in BOT.

The finding that the insulin dosage was lower in the SU + DPP-4i than SU group at the 6-month time point suggests that the combination of SU and DPP-4i may be more effective than SU alone even though the same HbA1c levels were achieved in both groups. Although increasing dose of insulin may affect HbA1c levels, this may be compatible with reports that the combination of SU and DPP-4i showed a greater glucose-lowering effect than SU monotherapy[23]. In this study, titration of insulin dosage was depends on the decision of each physician, because of real clinical practice setting. There are also limitations of this retrospective study.

At 6 months, approximately half the patients were continuing on the same regimen and one-fifth had achieved HbA1c levels < 7.0%. Thus, the characteristics of patients in whom BOT will be effective need to be clarified. In the present study, patients in the SU, DPP-4i, and SU + DPP-4i groups who had achieved HbA1c levels < 7.0% at the 6-month time point had lower BMI values at baseline. In addition, HbA1c levels at the initiation of insulin were lower in patients in the SU group and tended to be lower in the SU + DPP-4i group for those patients who achieved HbA1c < 7.0%. Although the number of patients in the DPP-4i group was too small to enable detection of a significant effect, the results suggest that BOT in combination with an SU, DPP-4i, or SU + DPP-4i may be effective in patients who have lower baseline BMI and HbA1c levels.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there were no significant differences in improvements in HbA1c and the percentage of patients continuing on the same regimen at the 6 month time point after BOT with an SU, DPP-4i, or SU + DPP-4i. The insulin dosage was lower in the SU + DPP-4i than SU group at the 6-month time point, even though the same HbA1c levels were achieved. BMI did not change in any of the three groups. Overall, the efficiency of BOT with an SU, DPP-4i, or SU + DPP-4i was limited because the percentage of patients continuing on the same regimen and achieving HbA1c < 7.0% was not adequate. However, BOT with insulin-secreting OADs, such as SU or DPP4i may be effective in some patients who have a lower BMI and lower HbA1c levels at baseline and it may become one of the choices of initiation of insulin. Further studies are still necessary to clarify which kind of ODAs are suitable as part of BOT.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant from the Japan Diabetes Foundation. The CoDiC software system belongs to the Japan Diabetes Clinical Data Management Study Group (JDDM). The authors thank the members of JDDM who contributed to this study.

Appendix

The following members of JDDM contributed to this study:

Dr. Nobuyuki Abe, Dr. Tahashi Ajihara, Dr. Keiko Arai, Dr. Kazumasa Chikamori, Dr. Motohiro Fujita, Dr. Yoshihide Fukumoto, Dr. Hiroshi Hayashi, Dr. Koichi Hirao, Dr. Hitomi Fujii, Dr. Kotaro Iemitsu, Dr. Tomo-o Igarashi, Dr. Yasushi Ishigaki, Dr. Koichi Iwasaki, Dr. Yoshio Kaku, Dr. Akira Kanamori, Dr. Sumio Kato, Dr. Mitsutoshi Kato, Dr. Koichi Kawai, Dr. Kenichi Kimura, Dr. Masashi Kobayashi, Dr. Mikihiko Kudo, Dr. Gendai Lee, Dr. Ikuro Matsuba, Dr. Masae Minami, Dr. Koji Nagata, Dr. Shin Nakamura, Dr. Hiroshi Ninomiya, Dr. Mariko Oishi, Dr. Akira Okada, Dr. Fuminobu Okuguchi, Dr. Hiroaki Seino, Dr. Hidekatsu Sugimoto, Dr. Hiromichi Sugiyama , Dr. Masato Takagi, Dr. Masahiko Takai, Dr. Hiroshi Takamura, Dr. Hiroshi Takeda, Dr. Kokichi Tanaka, Dr. Osamu Tomonaga, Dr. Akira Tsuruoka, Dr. Noriharu Yagi, Dr. Daishiro Yamada, Dr. Kohei Yamaguchi, Dr. Kuniko Yamaoka, Dr. Katsuya Yamazaki, Dr. Morifumi Yanagisawa, Dr. Hiroki Yokoyama, Dr. Atsuyoshi Yuhara

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1. De Witt, D.E., Hirsch, I.B. Outpatient insulin therapy in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a scientific review. (2003) JAMA 289(17): 2254-2264.

- 2. Diabetes Control and Complication Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. (1993) N Engl J Med 329(14): 977-986.

- 3. Ohkubo, Y., Kishikawa, H., Araki, E., et al. Intensive insulin therapy prevents the progression of diabetic microvascular complications in Japanese patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: a randomized prospective 6-year study. (1995) Diabetes Res Clin Pract 28(2):103-117.

- 4. Fritsche, A., Schweitzer, M.A., Haring, H.U., et al. Glimepiride combined with morning insulin glargine, bedtime neutral, protamine Hagedorn insulin, or bedtime insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes. A randomized, controlled trial. (2003) Ann Intern Med 138(12): 952-956.

- 5. Holtman, R.R., Thorne, K.I., Farmer, A.J. et al. Addition of biphasic, prandial, or basal insulin to oral therapy in type 2 diabetes. (2007) N Engl J Med 357: 1716-1730.

- 6. Fukushima, M., Usami, M., Ikeda, M., et al. Insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity at different stages of glucose tolerance: a cross-sectional study of Japanse type 2 diabetes. (2004) Metabolism 53(7): 831-835.

- 7. Oishi, M., Yamazaki, K., Okuguchi, F., et al. Changes in oral antidiabetic prescriptions and improved glycemic control during the years 2002–2011 in Japan (JDDM32). (2014) J Diabetes Invest 5(5): 581-587.

- 8. Kawamori, R., Eliaschewitz, G., Takayama, H., et al. Efficacy of insulin glargine and glimepiride in controlling blood glucose of ethnic Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. (2008) Diabetes Res Clin Pract 79(1): 97-102.

- 9. Fujita, N., Tsujii, S., Kuwata, H., et al. Predictor variables and an equation for estimating HbA1c attainable by initiation of basal supported oral therapy. (2012) J Diabetes Invest 3(2): 164-169.

- 10. Suzuki, D., Umezono, T., Miyauchi, M., et al. Effectiveness of basal-supported oral therapy (BOT) using insulin glargine in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. (2012) Tokai J Exp Clin Med 37(2): 41-46.

- 11. Deacon, D.J., Nauck, M.A. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a comparative review. (2011) Diabetes Obes Metab 13(1): 7-18.

- 12. Drucker, D.J., Nauck, M.A. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor antagonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. (2006) Lancet 368(9548): 1696-1705.

- 13. Goldstein, B.J., Feinglos, M.N., Lunceford, J.K., et al. Effect of initial combination therapy with sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, and metformin on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. (2007) Diabetes Care 30(8): 1979-1987.

- 14. Vilsboll, T., Rosenstock, J., Yki-Jarvinen, H., et al. Efficiency and safety of sitagliptin when added to insulin therapy in patients with type 2 daibetes. (2010) Diabetes Obes Metab 12(2):167-177.

- 15. Katsuno, T., Ikeda, H., Ida, K., et al. Add-on therapy with the DPP-4 inhibitor sitagliptin improves glycemic control in insulin-treated Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitusu. (2013) Endocr J 60(6): 733-742.

- 16. Kuzuya, T., Nakagawa, S., The Committee of the Japan Diabetes Society on the diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus, et al. Report of the Committee on the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. (2002) Diabetes Res Clin Pract 55(1): 65-85.

- 17. Alberti, K.G., Zimmet, P.Z. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes provisional report of a WHO consultation. (1998) Diabet Med 15(7): 539-553.

- 18. Kobayashi, M., Yamazaki, K., Hirao, K., et al. The status of diabetes control and antidiabetic drug therapy in Japan: a cross-sectional survey of 17,000 patients with diabetes mellitusu (JDDM 1). (2006) Diabetes Res Clin Pract 73(2): 194-204.

- 19. Ross, S.A., Tidesley, H.D., Ashkenas, J. Barriers to effective insulin treatment: the presistence of poor glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. (2011) Cur Med Res Opin 27(Suppl 3): 13-20.

- 20. Skovlund, S., Peyrot, M., on behalf of the DAWN International Advisory Panel. The diabetes attitudes, wishes, and need (DAWN) program: a new approach to improving outcomes of diabetes care. (2005) Diabetes Spectrum 18(3): 136-142.

- 21. Bretzel, R.G., Nuber, U., Landgraf, W., et al. Once-daily basal insulin glargine versus thrice-daily prandial insulin lispro in people with type 2 diabetes on oral hypoglycemic agents (APOLLO): an open randomized controlled trial. (2008) Lancet 371(9618): 1073-1084.

- 22. Odawara, M., Kadowaki, T., Naito, Y. Incidence and predictor of hypoglycemia in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes treated by insulin glargine and oral antidiabetic drugs in real-life: ALOHA post-marketing surveillance study sub-analysis. (2014) Diabetol Metab Syndr 6(1): 20-29.

- 23. Hermansen, K., Kipnes, M., Sitagliptin Study 035 Group et al. Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, sitagliptin, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled on glimepiride alone or on glimepiride and metformin. (2007) Diabetes Obes Metab 9(5): 733-745.