Counterfeit Drugs Set Alarm Bells Ringing: Comparative Analysis of Drug Policies

Affiliation

Occupational Health Administration, Ministry of Health, Khartoum, Sudan

Corresponding Author

Abdeen Mustafa Omer, Occupational Health Administration, Ministry of Health, Khartoum, Sudan, E-mail: abdeenomer2@yahoo.co.uk

Citation

Abdeen, M.O. Counterfeit Drugs Set Alarm Bells Ringing: Comparative Analysis of Drug Policies. (2018) J Pharm Pharmaceutics 5(1): 19-30.

Copy rights

© 2018 Abdeen, M.O. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Counterfeits medicines; Drug importers; Quality of medicines; Regulatory authorities

Abstract

The strategy of price liberalisation and privatisation had been implemented in Sudan over the last decade, and has had a positive result on government deficit. The investment law approved recently has good statements and rules on the above strategy in particular to pharmacy regulations. Under the pressure of the new privatisation policy, the government introduced radical changes in the pharmacy regulations. To improve the effectiveness of the public pharmacy, resources should be switched towards areas of need, reducing inequalities and promoting better health conditions. Medicines are financed either through cost sharing or full private. The role of the private services is significant. A review of reform of financing medicines in Sudan is given in this communication. Also, it highlights the current drug supply system in the public sector, which is currently responsibility of the Central Medical Supplies Public Corporation (CMS). In Sudan, the researchers did not identify any rigorous evaluations or quantitative studies about the impact of drug regulations on the quality of medicines and how to protect public health against counterfeit or low quality medicines, although it is practically possible. However, the regulations must be continually evaluated to ensure the public health is protected against by marketing high quality medicines rather than commercial interests, are held accountable for their conduct.

Introduction

The World Health Organisation[1] has defined drug regulation as a process, which encompasses various activities, aimed at promoting and protecting public health by ensuring the safety, efficiency and quality of drugs, and appropriateness accuracy of information[1]. Medicines regulation is a key instrument employed by many governments to modify the behaviour of drug systems. The regulation of pharmaceuticals relates to control of manufacturing standards, the quality, the efficacy and safety of drugs, labelling and information requirements, distribution procedures and consumer prices[2]. To assure quality of medicines, in most countries registration is required prior to the introduction of a drug preparation into the market. The manufacturing, registration and sale of drugs have been the subject of restricts regulations and administrative procedures worldwide for decades[3]. Nobody would seriously argue drugs should be proven to be 100% safe. No set of regulations could achieve that goal argue, because it is impossible and all drugs carry some risk[4].

Stringent drug regulation was introduced across many countries in the 1960s following the thalidomide disaster, and had since been embraced by the industry as a commercial essential seal of safety and quality[5]. In spite of the measures, many countries, especially developing one face a broader range of problems (Appendix 2). In several developing countries drug quality is a source of concern. There is a general feeling of high incidence of drug preparations that are not of acceptable quality[6]. For example, about 70% of counterfeit medicines were reported by developing countries[7]. Reports from Asia, Africa, and South America indicate 10% to 50% of consider using prescribed drugs in certain countries may be counterfeit[8]. For instance, in Nigeria fake medicines may be more than 60 - 70% of the drugs in circulation[9], and 109 children died in 1990 after being administered fake Paracetamol[10]. In Gambia the drug registration and control system resulted in the elimination of ‘drug peddlers’ and certain ‘obsolete and harmful’ drugs, as well as a large decrease in the percentage of brand and combination drugs[11]. The percentage of drugs failing quality control testing was found to be zero in Colombia, but 92% in the private sector of Chad[12]. Hence, it is very difficulty to obtain accurate data. The proportion of counterfeit drugs in the USA marketplace is believed to be small - less than 1 percent[12]. In[13] reported two cases of counterfeit medicines that found their way into legitimate medicine supply chain in the UK in 2004.

Poor quality drug preparations may lead to adverse clinical results both in terms of low efficacy and in the development of drug resistance[14]. Regulations are the basic devices employed by most governments to protect the public health against substandard, counterfeit, low quality medicines, and to control prices. Thorough knowledge of whether these regulations produce the intended effects or generate unexpected adverse consequences is critical. The World Health Organisation (WHO) undertook a number of initiatives to improve medicines quality in its member states and promote global mechanisms for regulating the quality of pharmaceutical products in the international markets. Yet, there are not any WHO guidelines on how to evaluate the impact of these regulations. There are numerous reports concerning drug regulations[15], but the published work on the impact of these regulations on the quality of medicines moving in the international commerce has been scarce. Findings from most published studies lack comparable quantitative information that would allow for objective judging whether and by how much progress on the various outcomes have been made by the implementation of the pharmaceutical regulations. To ignore evaluations and to implement drug regulation based on logic and theory is to expose society to untried measures in the same way patients were exposed to untested medicines[15].

The present policy of the national health-care system in Sudan is based on ensuring the welfare of the Sudanese inhabitants through increasing national production and upgrading the productivity of individuals. A health development strategy has been formulated in a way that realises the relevancy of health objectives to the main goals of the national development plans. The strategy of Sudan at the national level aims at developing the Primary Health Care (PHC) services in the rural areas as well as urban areas. In Sudan 2567 physicians provide the public health services (554 specialists, 107 medical registrars, 1544 medical officers, 156 dentists, and 206 pharmacists). Methods of preventing and controlling health problems are the following:

• Promotion of food supply and proper nutrition;

• An adequate supply of safe water and basic sanitation;

• Maternal and child health-care;

• Immunisation against major infectious diseases;

• Preventing and control of locally endemic diseases; and

• Provision of essential drugs.

This will be achieved through a health system consisting of three levels (state, provincial and localities), including the referral system, secondary and tertiary levels. Pharmacy management should be coordinated and integrated with other various aspects of health.

The following are recommended:

• The community must be the focus of benefits accruing from restructures, the legislature should protect community interest on the basis of equity and distribution, handover the assets to the community should be examined; and communities shall encourage the transfer the management of health schemes to a professional entity.

• The private sector should be used to mobilise and strengthen the technical and financial resources from within and outside the country to implement the services, with particular emphasis on utilisation of local resources.

• The government should provide the necessary financial resources to guide the process of community management of pharmacy supplies. The government should be a facilitator through setting up standards, specifications and rules to help harmonise the private sector and establish a legal independent body by an act of parliament to monitor and control the providers. Government should assist the poor communities who cannot afford service cost, and alleviate social-economic negative aspects of privatisation.

• The sector actors should create awareness to the community of the roles of the private sector and government in the provision of health and pharmacy services.

• Support agencies should assist with financial and technical support, training facilities, coordination, development and dissemination of health projects, as well as evaluation of projects.

Aims and Objective

The main purpose of this study is to analyse and determine the opinion of a group of pharmacists who are the owners or shareholders in the Sudanese medicine importing companies and their perception concerning the effects of the government’s new Pharmacy, Poisons, Cosmetics and Medical Devices Act has had on the quality of medicines in Sudan. To achieve this purpose the following questions would be answered:

Do the Sudan pharmacy legislations prohibit marketing of low quality medicines?

What is the impact of the transfer of veterinary medicines registration system to the Ministry of Animal Resources after the approval of the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 2001?

Does pre-marketing analysis of medicines help to detect the counterfeit medicines?

Does importation of non-registered• medicines by the government and non- governmental organisations exacerbate the problem of low quality medicine if any?

In Sudan, the researchers did not identify any rigorous evaluations or quantitative studies about the impact of drug regulations on the quality of medicines and how to protect public health against counterfeit or low quality medicines, although it is practically possible. However, the regulations must be continually evaluated to ensure the public health is protected against fake medicines by ensuring the exclusive marketing of high quality medicines rather than commercial interests, and the drug companies are held accountable for their conducts[16].

Medicines legislation framework in sudan

The availability of medicines in Sudan is controlled on the basis of safety, quality and efficacy. Thus, the government effects control in accordance with the Pharmacy, Poisons, Cosmetics and Medical Devices Act 2001 and its instruments. The Federal or State Departments of Pharmacy (DOP) and directives issued orders. The primary objective of both Federal and States’ Departments of Pharmacy is to safeguard public health by ensuring all medicines and pharmaceuticals on the Sudan market meet appropriate standards of safety, quality and efficacy. The safeguarding of public health is achieved largely through the system of medicines’ registration and licensing of pharmacy premises.

The first Pharmacy and Poisons Act was enacted in 1939. This act had been amended three times since then. In 2001 amendments, cosmetics and medical devices were also brought under its purview. Thus, the name was changed to Pharmacy, Poisons, Cosmetics and Medical Devices Act (hereafter the Act). The act regulates the compounding, sale, distribution, supply, dispensing of medicines and provides different levels of control for different categories, e.g., medicines, poisons, cosmetics, chemicals for medical use and medical devices.

The act makes provision for the publication of regulations and guidelines by the Federal Pharmacy and Poisons Board (FPPB), the pharmaceutical regulatory authority and its executive arm - the Federal General Directorate of Pharmacy (FGDOP). The FGDOP regulates mainly four aspects of medicines use: safety, quality, efficacy and price. Traditionally, governments in many countries, particularly developed nations have attempted to ensure the efficiency, safety, rational prescribing, and dispensing of drugs through pre-marketing registration, licensing and other regulatory requirements[17]. When applying to register the medicine manufacturers and importers are required to furnish the FGDOP with a dossier of information including among others, the indication of the medicine, its efficacy, side effects, contraindication, warnings on usage by high risk groups, price, storage and disposal[17].

The role of the FGDOP includes among others:

Regulation and control of the importation, exportation, manufacture, advertisement, distribution, sale and the use of medicines, cosmetics, medical devices and chemicals

Approval and registration of new medicines-the act requires FGDOP should register every medicine before be sold or marketed. Companies are required to submit applications for the registration of medicines for the evaluation and approval;

Undertake appropriate investigations into the production premises and raw materials for drugs and establish relevant quality assurance systems including certification of the production sites and regulated products; Undertake inspection of drugs’ whole and retail sellers owned by both public or private sectors; Compile standard specifications and regulations and guidelines for the production, importation, exportation, sale and distribution of drugs, cosmetics, etc.

Control of quality of medicines: This will be done by regular inspection and post-marketing surveillance;

Licensing of pharmacy premises (i.e., pharmaceutical plants, wholesalers and retail pharmacies);

Maintain national drug analysis laboratories for the pre- and post- marketing analysis of medicines;

Coordination with states departments of pharmacy to ensure the enforcement of the act and its rules and directives.

Health and pharmacy systems

The health system in Sudan is characterised by heavy reliance on charging users at the point of access (private expenditure on health is 79.1 percent), with less use of prepayment system such as health insurance. The way the health system is funded, organised, managed and regulated affects health workers’ supply, retention, and the performance. Primary Health Care was adopted as a main strategy for health-care provision in Sudan and new strategies were introduced during the last decade, including:

• Health area system.

• Polio eradication in 1988.

• Integrated management of children illness (IMCI) initiative.

• Rollback malaria strategy.

• Basic developmental need approach in 1997.

• Safe motherhood, making pregnancy safer initiative, eradication of harmful traditional practices and emergency obstetrics’ care programmes.

The strategy of price liberalisation and privatisation had been implemented in Sudan over the last decades, and has had a positive result on the government The investment law[18] approved recently has good statements and rules on the above strategy in particular to health and pharmacy areas. The privatisation and price liberalisation in healthy fields has to re-structure (but not fully). Availability and adequate pharmacy supplies to the major sectors. The result is that the present situation of pharmacy services is far better than ten years ago.

The government of Sudan has a great experience in privatisation of the public institutions, i.e., the Sudanese free zones and markets, Sudan telecommunications (Sudatel) and Sudan airlines. These experiences provide good lessons about the efficiency and effectiveness of the privatisation policy. Through privatisation, the government is not evading its responsibility of providing health-care to the inhabitants, but merely shifting its role from being a provider to a regulator and standard setter. Drug financing was privatised early in 1992. Currently, the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) has privatised certain non-medical services in hospitals such as catering services, security and cleanings.

The overall goal of the CMS ownership privatisation is to improve access to essential medicines and other medical supplies in order to improve health status of the inhabitants particularly in far states (e.g., Western and Southern States).

Establishment of alternative ownership for the CMS can be achieved by selling the majority of shares to the private sector.

This will achieve the following objectives:

• High access to essential medicines of good quality and affordable prices to the states’ population and governments.

• Efficiency and effectiveness in drug distribution system to avoid the serious pitfalls and incidences that was reported during the last ten years in the CMS.

• Equity by reaching all remote areas currently deprived from the formal drug distribution channels.

• Improvement of the quality and quantity of delivery of medicines to the public health facilities.

The above objectives are expected to:

• Increase geographical and economic access to essential medicines in all states (i.e., in both rural and urban areas) to reach at least 80% of the population (currently less than 50% of population have access to essential medicines).

• The tax collection from the new business becomes more efficient and will increase after privatisation. The tax revenues could be used to finance other health-care activities.

• If the government reserves some shares (not more than 50%) in the new business, then its shares’ profit could be used to finance free medicines project in hospitals outpatients’ clinic, and other exempted medicines, e.g., renal dialysis and haemophilic patients’ treatment.

Privatisation of public pharmaceutical supplies

The term privatisation has generally been defined as any process that aims to shift functions and responsibilities (totally or partially) from the government to the private. More broadly meaning, it refers to the restriction of government’s role and putting forward some methods or policies in order to strengthen the free market economy[19]. Privatisation can be an ideology (for those who oppose government and seek to reduce its size, role, and costs, or for those who wish to encourage diversity, decentralisation, and choice) or a tool of government (for those who see the private sector as more efficient, flexible, and innovative than the public sector)[19]. In[19] contends that “the invisible hand of the market is more efficient and responsive to the consumer needs and the public administrative budgets consume large portion of tax monies that could otherwise be used for service delivery”. The emphasis is on improving the efficiency of all public enterprises, whether retained or divested.

Privatisation may take many forms including:

• Elimination of a public function and its assignment to the private sector for financial support as well as delivery (police, and fire departments, schools, etc.). Opponents characterise this as “load-shedding”.

• Deregulation: the elimination of government responsibility for setting standards and rules concerning goods or services.

• Assets sales: the selling of a public asset (city buildings, and sports stadiums) to private firms.

• Vouchers: are the government provided or financed cards or slips of paper that permit private individuals to purchase goods or services from a private provider (food stamps) or circumscribed list of providers.

• Franchising: the establishment of models by the public sector that is funded by government agencies, but implemented by approved private providers.

• Contracting: the government financing of services, choice of service provider, and specification of various aspects of the services laid out in contracts with the private-sector organisation that produces or delivers the services.

• User fees: public facilities such as hospitals that maximise their income or finance some goods from private sources, either through drug sales or other services. This kind of privatisation has been applied in Sudan since the early 1990s, as the health financing mechanism (especially for medicines).

In Sudan, the government has decided to distance itself from direct involvement in business, and thus divest most of its interests whether in loss or profit making public enterprises. The public reform programme was set firmly in the context of the broader reforms[19], which were introduced in 1992. It had become clear the previous policies had delivered led to poor results. This reform based on the transfer of activities vested with the government institutions to the private sector. It signalled the government intention to reduce its presence in the economy, to reduce the level and scope of public spending and to allow market forces to govern economic activities. Privatisation also forms part of the government strategy of strengthening the role of the private in the development to achieve the vision of the 25 years strategy in which the private sector will be the engine for economic growth. The privatisation started in 1992 by liberalisation of local currency, foreign exchange transactions, internal and external trade, prices and health services (e.g., user fee as a mechanism of drug financing and other services). This reform had led to greater reliance on individual initiative and corporate accountability rather than on government as a decision-maker in business matters.

The privatisation policy goal is to improve the performance of the public sector companies, so that they can contribute to the growth and the development of the economy by broadening ownership, participation in management, and stimulating domestic and foreign private investment.

The following are the primary objectives, which have been defined in the government’s policy statement on public sector reform[19]:

• Improve the operational efficiency of enterprises that are currently in the public sector by exposing business and services to the greatest competition for the benefit of the consumer and the national economy.

• Reduce the burden of public enterprises on the government’s budget by spreading the shares’ ownership as widely as possible among the population.

• Expand the role of the private sector in the economy (permitting the government to concentrate on the public resources) on its role as provider of basic public services, including health, education, social infrastructure, and to compact the side effects of the privatisation.

• Encourage wider participation of the people in the ownership and management of business.

In pursuing the primary objectives the privatisation policy aims to transform the performance of most significant enterprises in the public sector and ensure liquidation of all viable and non-viable public enterprises as soon as possible through commercialisation, restructuring and divesture.

Public sector reform efforts are thus aimed at reducing government dominance and promoting a larger role for the private sector, while improving government’s use of resources. Movement towards those goals in some countries is supported by components of a structural adjustment loan, which helped initiate the programme and establish the legislative and institutional base.

Opponents argue that the original objectives of state ownership were to ensure the corporate sector of the economy was in national hands rather than being controlled by either foreign investors or the minorities that enjoyed business dominance upon independence. A further objective was to use investment in state firms to accelerate development in a situation, in which private sector was reluctant to take risks.

Medicines legislation framework in sudan

The availability of medicines in Sudan is controlled on the basis of safety, quality and efficacy. Thus, the government effects control in accordance with the Pharmacy, Poisons, Cosmetics and Medical Devices Act 2001 and its instruments. The Federal or State Departments of Pharmacy (DOP) and directives issue orders. The primary objective of both Federal and States’ Departments of Pharmacy is to safeguard public health by ensuring all medicines and pharmaceuticals on the Sudan market meet appropriate standards of safety, quality and efficacy. The safeguarding of public health is achieved largely through the system of medicines’ registration and licensing of pharmacy premises.

The first Pharmacy and Poisons Act was enacted in 1939, and has been amended three times since. In the 2001 amendments, cosmetics and medical devices were also brought under its purview. Thus, the name was changed to Pharmacy, Poisons, Cosmetics and Medical Devices Act (hereafter the Act). The act regulates the compounding, sale, distribution, supply, dispensing of medicines and provides different levels of control for different categories, e.g., medicines, poisons, cosmetics, chemicals for medical use and medical devices.

The act makes provision for the publication of regulations and guidelines by the Federal Pharmacy and Poisons Board (FPPB), the pharmaceutical regulatory authority and its executive arm - the Federal General Directorate of Pharmacy (FGDOP). The FGDOP regulates mainly four aspects of medicines use: safety, quality, efficacy and price. Traditionally, governments in many countries, particularly developed nations have attempted to ensure the efficiency, safety, rational prescribing, and dispensing of drugs through pre-marketing registration, licensing and other regulatory requirements. When applying to register the medicine manufacturers and importers are required to furnish the FGDOP with a dossier of information including: the indication of the medicine, its efficacy, side effects, contraindication, warnings on usage by high risk groups, price, storage and disposal.

Sudan medicines quality measures

The following summarises the quality measures of all medicines.

Registration of medicines: The FGDOP is responsible for the appraisal, and registration of all medicines and other pharmaceuticals for both human and veterinary use on the Sudan market. It is also responsible for the verification of the competence of manufacturing companies, the manufacturing plants, the ability to produce substances or products of high quality before registering these companies and allowing them to apply for registration of their products in Sudan. When necessary, visits conducted to those companies and their manufacturing units, to verify their compliance with good manufacturing practice recommended by the WHO. The applicant for registration of pharmaceutical product must submit all prescribed data and the certificates required under the WHO certification scheme for a pharmaceutical product moving into international commerce, and any other information that is necessary for assuring the quality, efficiency and stability of the product through its shelf life[19].

Licensing of pharmacy premises: The licensing is a registration exercise to provide the DOP at state level (Federal level in case of local manufacturing plants) with the information necessary for the full implementation of the Act. Licenses are granted for a period of one year, and may be renewed at the end of December every year (applications to the relevant DOP before expiry of the current license). To improve the effectiveness of the public pharmacy, resources should be switched towards areas of need, reducing inequalities and promoting better health conditions. Medicines are financed either through cost sharing or full private. The role of the private services is significant. The present policy of the national health–care system in Sudan is based on ensuring the welfare of the Sudanese inhabitants through increasing national production and upgrading the productivity of individuals. The strategy of price liberalisation and privatisation had been implemented in Sudan over the last decade, and has had a positive result on government deficit.

There are three major licenses as follows:

a) License A (Wholesaler License)

The pharmaceutical importing companies have subjected to two broad categories of regulation. Those are the registration and administrative process, and the regulation of quality manufacturing standards, efficacy and information disclosure.

License A authorises the holder to sell a registered medicine to a person who buys the medicine for the purpose of sale or supply to someone else under the direct supervision of a registered pharmacist or licensed medical doctor. Licensing of the wholesalers involves identification of the wholesaler and suitability of the premise. There are 175 wholesalers in Sudan. The majority (162 wholesalers) are local agents for the goods manufactured from abroad. The rest are 13 “local manufacturer” wholesalers at Khartoum State (KS) and distribute the medicines to the whole country. Wholesalers are inspected by the state DOP before license is granted and thereafter at least once per year.

b) License B (Retail Pharmacy License)

Authorises the holder to sell a registered medicine to a patient on prescription or over-the counter basis under direct supervision of the registered pharmacist. The pharmacies are inspected before a license is issued and thereafter at least twice per year.

c) License D (Manufacturer’s License)

Manufacturing includes many processes carried out in the course of making a medicinal product. A manufacturer’s license covers all aspects- bulk drug, product manufacture, filling, labelling and packaging- under supervision of a registered pharmacist. There are 13 generic manufacturing sites at Khartoum State (KS). The Federal DOP inspects each one. Good manufacturing practice (GMP) is the basis of the inspection. Effective control of quality requires a manufacturer possess, and the appropriate facilities with respect to premises, equipment, staff, expertise and effective well-equipped quality control laboratory. Normally, before a license is granted, an inspection of premises is made and Federal DOP takes this into account. The local manufacturers produce 65 pharmaceutical dosage forms of essential drugs and cover 60% of the Central Medical Supplies Public Organisation (CMSPO) purchases.

In Sudan there are two types of retail pharmacy:

Commercial private pharmacies: These are private establishments retailing registered drugs and medical supplies at a mark-up of 18%. The source of the drugs and pharmaceuticals is private wholesalers. In 2002, though unlawful, the CMSPO started to sell its non-registered medicines to the private pharmacies. By the end of 2004, there were 779 private pharmacies in Sudan.

People’s Pharmacies: These are quasi-public establishments retailing drugs and medical supplies below the market prices to improve access and availability of pharmaceuticals. They were founded in the early 1980s as a pilot study for a drug cost recovery system. Those differ from the private commercial pharmacies. Firstly, in having access to the CMSPO drugs, i.e., generic and large pack products, in addition the brand products from the private wholesalers. Secondly, the peoples’ pharmacies are only owned by public organisations (e.g., hospitals, peoples’ committees, trade unions and Non Governmental Organisations (NGOs)). Mark-up on cost for drugs from the CMSPO (35%), and from private drug wholesalers (profit margin is 10%). However, they have become commercialised now and operate in a similar way to private pharmacies. The total number of such pharmacies was approximately 200 in Sudan.

Public sector medicines supply system

In Sub-Saharan Africa countries discussions about medicine distribution system reform have concentrated on ways to improve sustainability and quality of access to essential medicines. These discussions also include debate on the impact of privatisation of public drug supply organisations on effectiveness, efficiency, quality and cost of medicines in the public health facilities, as well as on the respective role of the public and private sectors.

Until the mid 1980s, some governments in Africa (i.e., Mali and Guinea) assumed responsibility for providing drugs to their citizens. The private distribution of all drugs including aspirin was illegal. In many countries, including Sudan there were two parallel government distribution systems. The public health network of hospitals and health centres gratuitously distributed drugs. In the public sector pharmacies, the drugs were sold to the public at subsidised prices.

During the 1990s, Sudan initiated a number of initiatives to establish drug-financing mechanisms as part of the health reform process and decentralised decision-making at a state level. In 1992 when a law was passed, medicines were no longer free of charge (i.e., privatised) in the public health system. The aim of the government is to increase equitable access to essential medicines, especially at the states’ level. As a result the Central Medical Stores, which was responsible for medicines supply system of the public health facilities, became an autonomous drug supply agency, and was renamed as the Central Medical Supplies Public Corporation (CMS) and operated on cash-and-carry basis. It was capitalised and an executive board was installed. Since states and federal hospitals have to buy their own medicines, and other medical supplies. They organised their own transport means and distribution to their primary health-care facilities and hospitals. In addition, all hospitals became financially autonomous entities and have had to organise their own medicines procurement system.

The public drug supply system has not been working well throughout Sub-Saharan Africa and this includes Sudan. There are serious shortages or no medicines at all, particularly in rural areas. A study in Cameroon found the rural health centres received only 65% of the stock designated for them, and 30% of the medicines that arrived at the centres did not reach the clients. The loss rate after arrival in hospitals was estimated at 40%. In Sudan, Graff and Evarard (2003) who visited the country on a WHO mission reported, “Although the cash-and-carry system took off well, but lack of sufficient foreign exchange hampered the CMS procurement activities and resulted in low stock levels of all medicines and even stock out of life-saving products. Hospitals had to purchase the medicines from elsewhere and often had to buy from private sector. Overall hospitals’ budgets were tied to allocate drug budget and sales income was not sufficient to cover the purchase of needed medicines supplies. As a result the medicines were not available most of the times. The in- or outpatients with their prescriptions were directed to the private pharmacies. In 2003, Khartoum Teaching Hospital-the biggest hospital in Sudan (not further than 5 km away from the CMS) had a medicine stock of only LS 83,000 (US$ 31). This would not fill one prescription for an anaemic patient as a result of renal failure. This is a common practice that patients or their relatives are given prescriptions to buy any pharmaceutical supplies that are needed including drugs and other disposables from private sector pharmacies.

Many ministries of health, services’ providers and researchers have identified many characteristics that lead to poor performance in Africa public drug supply systems. These characteristics include:

Absence of competition: Competition is the best way to ensure the goods and services desired by the consumer are provided at the lowest economic cost. Given the customers (i.e., public health facilities) freedom of choice enables market forces to provide sustained pressures on companies to increase efficiency. Privatised companies generally operate in a competitive market environment.

Insufficient funding: For example in Sudan with exception of Khartoum, Gezira and Gedaref states, all other states do not have enough funds to establish an efficient drug supply system. In spite of being profit-making organisation, the CMS failed to avail such funds during the past 14 years.

Inefficient use of available resources: Since the CMS was established in early 1990s working as a profit-making organisation. Due to the absence of privatisation the CMS engaged in an instalment of repackaging joint venture pharmaceutical factory in 1999 and recently announced its commitment to build a pharmaceutical city with not less than US$ 20 million, despite the lack of life-saving medicines in the public health facilities. Such amount could be sufficient to establish a reliable supply system for all states of Sudan. The lack of prioritisation is a typical symptom and sign of most public organisations.

Poor management: There are a number of constraints inherent in operating government drug supply service.

These constraints comprise:

(a). Civil servants are hired, rather than persons with business experience and skills. Managers confront different challenges in public setting. They are not easily hired or fired. The lack of accountability results from the lack of shareholders, who would be free to remove incompetent administrators.

(b). Even if the services can recruit outside of civil service, the wages are often too low to attract experienced managers. In addition, the managers do not share in dividends or other monetary activities as do private managers and incentives for doing well are often attenuated in a bureaucracy.

(c). There are cultural and structural conditions that promote corruptions including enormous pressure of wages earners to support an extended family and a strong incentive to more than their fixed government wage, traditional gift giving practice and a proprietary view of public offices.

Privatisation of the CMS’s ownership

The public sector drug supply institutions have not succeeded (CMS is not exceptional) so far in organising a reliable and regular essential drug supply for the public health facilities[20]. One of the most criticisms of the public drug supply system generally in Africa and particularly in Sudan is how badly they are internally managed. There are those who agree the greater amount of real pharmaceutical resources could be made available to the public health- care system and the access to essential medicines could be significantly increased, if managerial efficiency of the system improved[20]. Given the limitation of the public sector is due to constraints inherent in operating a government drug supply organisation system. Even after autonomous experience - and the stabilised role of the private sector organisations such as private pharmaceutical sectors organisations (rapid increase in importing companies, manufacturers and pharmacies). Telecommunications, e.g., Sudatel is one of the obvious solutions of choice for the government pharmaceutical policy would be to privatise the ownership of the CMS to the extent possible.

Advantages of private agencies

There are many arguments in favour of privatisation of public institutions. Advocates of this method claim privatisation have the following advantages:

• Privatisation is efficient and effective because it fosters and initiates competition. The competition among firms drives the cost down. Empirical studies clearly prove the cost of the services provided by the government is much higher than when

• the services are provided by private contractors. For example CMS’s declared mark-up on cost (35%) amounted to 2.3 times the private mark-up (15%). In addition, private sector pays taxes, customs and other

• governmental fees (CMS exempted).

• Privatisation also provides better management than the public management. Because decision making under privatisation is directly related to the costs and benefits. In other words, the privatisation fosters good management because the cost of the service is usually obscured.

• Privatisation would help to limit the size of government at least in terms of the number of employees. On the other hand, it is a fact that overstaffing is common in publicly owned enterprises.

• Privatisation can help to reduce dependence on a government monopoly, which causes inefficiencies and ineffectiveness in services.

• Private sector is more flexible in terms of responding to the needs of citizens. Greater flexibility in the use of personnel and equipment would be achieved for short-term projects, part-time work, etc. Bureaucratic formalities are very common when government delivers the service. Less tolerance and strict hierarchy in bureaucracy are the reasons of the inflexibility in publicly provided services.

Medicines supply system

The act, for the first time in Sudan has given the responsibility of veterinary medicines to separate committees. The Ministry of Animal Resources took the law “in hand”, and started the registration of veterinary medicines and the licensing of the veterinary medicines premises. The conflict in the shared authorities between the Ministry of Health and the chairman of the FPPB lead to the freezing of the Board since October 2002. The FGDOP continues in the process of medicines registration, inspection of the pharmaceutical premises and the licensing as before establishment of the FPPB.

The act also obliges the states’ governments to take all steps necessary to ensure compliance with marketing of registered medicines in licensed premises. But, the weaknesses of the regulatory infrastructure and lack of political commitment at state levels, the leakage of low quality, unregistered medicines to those states are highly suspected. This left the door widely opened for informal marketing of medicines particularly in far states. The states regulatory authorities should take the advantage of the legal authority granted by the Sudan constitution and the Pharmacy, Poisons, Cosmetics and the Medical Devices Act 2001 to enforce the regulations and increase the frequency of the inspection visits to drug companies and retail pharmacies.

Experience has shown the poor regulation of medicines can lead to the prevalence of substandard, counterfeit, harmful and ineffective medicines on the national markets and the international commerce. The Sudanese pharmaceutical legal framework was described as one of the strictest pharmaceutical system in the region. One of the great loopholes in this system was found to be the increased number of non-registered medicines-governmental sources such as the Central Medical Supplies Public Organisation (CMSPO) and not-for-profit non-governmental Organisations (NGOs). Respondents were hopeful the double standard of rules enforcement would be lifted after the new national unity government take over, arguing the current situation in which public organisations (such as the CMSPO) sell non-registered medicines to the private pharmacies could enhance trading of counterfeit medicines and create unfair competition environment.

One of the respondent reported, “It is disturbing, in spite of the existence of appropriate legislation, illegal distribution of medicines by the CMSPO. The CMSPO continues to flourish, giving the impression the government is insensitive to harmful effect on the people of medicines distribution unlawfully, and some are of doubtful quality”. During the past three years the CMSPO started to sell unregistered medicines to the private pharmacies. The CMSPO practice (he added) will undermine the inspection and medicines control activities and ultimately jeopardise the health of the people taking medication.

Not surprisingly all respondents strongly agreed the increased number of sources of non-registered medicines will lead to entrance of low quality medicines. This result is inline with the WHO recommendation, which encourages the regulatory authorities and state members` government to register all medicines before the marketing. The medicines imported by public sector organisations are not excluded.

The FGDOP should define the norms, standards and specifications necessary for ensuring the safety, efficacy and quality of medicinal products. The availability, accuracy and clarity of drug information can affect the drug use decisions. The FGDOP does not have a well-developed system for pre-approval of medicines labels, promotional, and advertising materials. The terms and conditions under, which licenses to import, manufacture and distribute will be suspended, revoked or cancelled. This should be stringently applied to public, private and not-for-profit NGOs drug supplies organisations.

The predominant view, shared between the medicines’ importers is the current pharmacy legislation to some extent satisfactory and managed to prohibit the marketing of low quality medicines. The recent post-marketing study carried by the National Drug Quality Control Laboratories, suggested the power of the current regulation is overestimated. The finding of this communication indicates the application procedures of the current measures to ensure the quality of medicines should be revisited. The technical complexity of regulations, political, commercial and social implications, makes necessary a degree of mutual trust between concerned stakeholders (i.e., suppliers, doctors, pharmacists, consumer representatives and government agencies).

Rational for the research

The drug distribution network in Sudan during the past few years was in a state of confusion. It consists of open market, drug vendors (known as home drug store), community (private) pharmacies, peoples’ pharmacies, private and public hospitals, doctors’ private clinics, NGOs clinics, private medicines importers (whole salers), public wholesalers (i.e., Central Medical Supplies and Khartoum State Revolving Drug Fund) and local pharmaceutical manufacturers. It is a common phenomenon in far states (e.g., Western and Southern states) to see street sellers or mobile sellers (hawkers) sell cigarettes, perfumes, orange and astonishingly medicines that range from Paracetamol and Aspirin tablets to antibiotics and anti-malarial drugs including injections. The medicines are usually left under the sun, and such conditions could facilitate the deterioration of the active ingredients.

The states’ departments of pharmacy statutorily licensed community and Peoples’ pharmacies. A superintending pharmacist, who is permanently registered with the Sudan Medical Council and licensed, oversees the pharmacy any time it is opened for business[19]. With such pharmacies there should not be any serious of the sale of fake drugs. Unfortunately, however there are many pharmacies working without qualified pharmacists.

This study is significant because the people right to health include the right access to a reliable standard of health care and assurance the medicines received are not only genuine but also safe, effective, of good quality and affordable[20]. The Sudan government has designed various ways to protect the public against low quality medicines. It is expected to equip the departments of pharmacy especially in remote areas, poor states with material and trained staff to effectively perform duties.

A recent unpublished post-marketing surveillance revealed that 35% of the CMSPO samples and 16% of the private companies (registered products) samples obtained from different pharmacy shops failed to pass the quality test[20]. However, very few studies if any have been undertaken to evaluate the impact of the regulations put in place by the government long time ago.

This study should reveal strength and weaknesses of the legal pharmaceutical framework in Sudan from drug importers perspective. The findings of this investigation would be instructive to regulatory authorities in the developing countries. It also highlights how systematically the drug companies perceived the role of pharmacy regulations in assuring high quality of medicines and what suggestions (if any) they had to make in order to improve the regulatory framework.

Methodology

The study proposal was discussed to identify and improve the quality of medicines in Sudan. The survey was deliberately drug importers biased, as low quality medicines from informal sources will affect their business[21]. The author then designed a self-administered questionnaire of 14 close-ended questions and one open question.

The questionnaire was designed to address main six issues:

• The quality of medicines.

• The consequences of splitting of the regulatory authority functions between the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) and the Ministry of Animal Resources (MOAR).

• Views on the role of the recently established Federal Pharmacy and Poisons Board, and Pre- and Post-Marketing Surveillance.

• Decentralisation, and

• Increased number of suppliers of non-registered medicines.

The final version of the questionnaire had been tested (three pharmacists working with drug companies in Sudan were asked to fill the questionnaire and feed the author back whether there was unclear question or not). The questionnaire was tested to make sure all relevant issues were covered, pre-coded and adjusted before its distribution (Appendix 1).

The questionnaire was distributed to all forty participants at a seminar held in July 2004. Total numbers of drug importers companies were 175 in 2004.

The seminar was organised by the FGDOP on the new proposal to limit (agree a ceiling for each item) the number of commercial brand product registered from each generic drug (the current situation is open). The owners and shareholders of drug companies were the participants. This was seen by the author as a great opportunity to collect data of the drug importers’ perspective on the quality of medicines. Hence, the study participants were so busy and it was very difficult to devote a time to be interviewed by the author. In addition, the postal services in Sudan are poor (too slow and unreliable).

Before the beginning of the seminar, the participants were requested by the secretariat to complete the questionnaire and hand it back to the secretariat before departure. The participants were informed it is anonymous questionnaire. The reasons given to the participants for filling out the questionnaire was to enable an academic research to assess the impact of the new act on the quality of medicines. Finally, at the end of the seminar, the secretariat managed to get 30 questionnaires, representing 75% out of 40 distributed.

The information necessary to conduct this evaluation was collected from 30 pharmacists working with medicines’ importing companies. Data gathered by the questionnaire were electronically analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 12.0 for windows.

Results and Discussion

The drug distribution network in Sudan consists of open market, drug vendors (known as home drug store), community (private) pharmacies, people’s pharmacies, private and public hospitals, doctors’ private clinics, NGOs clinics, private medicines importers (wholesalers), public wholesalers (i.e., Central Medical Supplies and Khartoum State Revolving Drug Fund) and local pharmaceutical manufacturers. The states’ departments of pharmacy statutorily licensed community and Peoples’ pharmacies. A superintending pharmacist, who is permanently registered with the Sudan Medical Council and licensed, oversees the pharmacy any time it is opened for business[22]. With such pharmacies there should not be any serious of the sale of fake drugs. Unfortunately however, there are many pharmacies working without qualified pharmacists[23]. During the last decade, the pharmacy workforces have witnessed a significant increase in the number of pharmacies, drug importing companies and pharmaceutical manufacturers as shown in Table 1. In the public sector, adoption of cost sharing policy as a mechanism of financing for essential medicines at full price cost requires far more expertise than simply distributing free medicines. This policy increases the demand for pharmacists in hospitals. The new concept of pharmaceutical care and recognition pharmacists as health care team members will boost the demand for the skilled registered pharmacist (PHRs). The Federal Ministry of Health (MOH) faces two major issues with the PHRs: first, the current shortage of pharmacists in the public sector; secondly, the future role of pharmacists within the health cares system.

Table 1: Pharmacists labour market[23]

| Institutions | 1989 | 2003 | Increase in (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faculties of Pharmacy | 1 | 7 | 600% |

| Registered Pharmacists | 1505 | 2992 | 99% |

| Public Sector Pharmacists | 162 | 300 | 85% |

| Hospital Pharmacies | 205 | 304 | 48% |

| Community Pharmacies | 551 | 779 | 41% |

| Drug Importing Companies | 77 | 175 | 127% |

| Drug Manufacturers | 5 | 14 | 180% |

Table 2: Pharmacists distribution at state levels[24].

| State | Number of pharmacists |

|---|---|

| Department of Pharmacy (DOP) Khartoum State* | 8 |

| DOP-North Darfur | 7 |

| DOP-Sennar | 2 |

| DOP-North Kordofan | 5 |

| DOP-South Kordofan | 7 |

| DOP-White Nile | 2 |

| DOP-Kassala | 7 |

| DOP-River Nile | 3 |

| DOP-Northern State | 3 |

| DOP-Al Gezira* | 6 |

| Total** | 50 |

The Pharmacists who work with Revolving Drug Funds are not included.

Information about other States is not available (10 Southern states, 2 Darfur states, 2 Eastern states, 1 Blue Nile state, and 1 West Kordofan state)

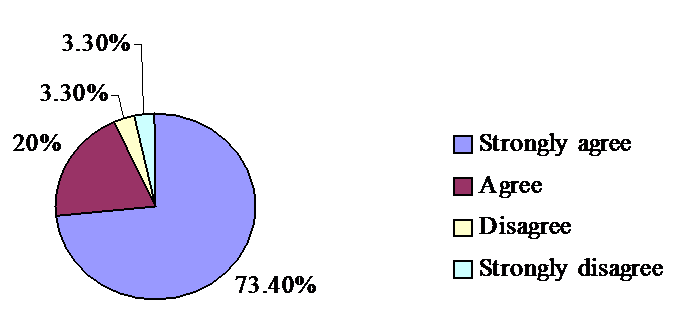

Around 3000 pharmacists are registered in Sudan. Only 300 (10%) works with the public sector. 25, 25, 20 pharmacists were employed in Khartoum, Khartoum North and Omdurman hospitals respectively. Some states (e.g., Southern states has only 2 pharmacists) were not included in Table 2. This anomaly seems to imply the number of pharmacists in the public sector (has not only been insufficient in absolute terms, but also has been inefficient in its distribution). This number will be depleted and the situation may be getting worse. One reason is migration to the private sector. The results are described in Figure 1.

In the absence of past baselines data, decisive conclusions should not be drawn from this article regarding the impact of the pharmaceutical regulations on ensuring good quality medicines. Nevertheless, the survey did serve to confirm the general impression about medicines of good quality on the Sudanese market.

89% of respondents considered the medicines on the Sudanese market are generally of good quality. Although 55% of the study population either strongly agree (21%) or agree (34%) with the statement the drug legislations in Sudan prohibit marketing of low quality medicines. 35% believe the transfer of authority to recently established the Federal Pharmacy and Poisons Board (FPPB) will undermine on medicines quality assurance system. 38% of the participants thought the replacement of the FGDOP by the FPPB will improve the medicines quality control system.

Only one-fourth of respondents were not very confident in current systems and safeguard to ensure the quality of medicines. 69% of respondents were somewhat confident in the FGDOP regulates and monitors quality of medicines. The majority 79% of respondents agree with the statement “decentralisation of licensing and inspection of pharmaceutical premises will improve the pharmaceutical control”.

After the approval of the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 2001, the Ministry of Animal Resources (dominated by veterinarians) took the responsibility of registration of veterinary medicines and the licensing of the whole and retail sellers of veterinary medicines. As expected, 91% of respondents thought, the splitting of drug registration between the MOH and the MOAR weakens the medicines control, compared with only 9 % who thought the arrangement would improve the quality of medicines. One of the respondents added: “The splitting of the drug authority between MOH, which according to the Sudan constitution is fully responsible for the public health and MOAR will create contradiction in lines of commands and public health would be compromised”. 84% of respondents agreed with the statement “This new arrangement could cause conflict between two regulatory authorities”. 93% of participants either strongly agree (73%) or agree (20%) the increased number of non-registered medicines distributors will facilitate the marketing of low quality medicines (Figure 1). When asked about updated requirements of medicines registration, only 25% of respondents thought the updated requirements are not sufficient to prevent marketing of low quality medicines. Nearly three-quarters (71%) agreed the pre-marketing surveillance is not enough to ensure the quality of medicines. The law regulating medicines was judged by the respondents as generally adequate (68%).

Figure 1: The increased numbers of non-registered medicines importers will facilitate the marketing of low quality medicines.

Medicines supply system

The Act, for the first time in Sudan has given the responsibility of veterinary medicines to separate committees. The Ministry of Animal Resources took the law “in hand”, and started the registration of veterinary medicines and the licensing of the veterinary medicines premises. The conflict in the shared authorities between the Ministry of Health and the chairman of the FPPB lead to the freezing of the Board since October 2002. The FGDOP continues in the process of medicines registration, inspection of the pharmaceutical premises and the licensing as before establishment of the FPPB. The Act also obliges the states’ governments to take all steps necessary to ensure compliance with marketing of registered medicines in licensed premises. But, the weaknesses of the regulatory infrastructure and lack of political commitment at state levels, the leakage of low quality, unregistered medicines to those states are highly suspected. This left the door widely opened for informal marketing of medicines particularly in far states. The states regulatory authorities should take the advantage of the legal authority granted by the Sudan constitution and the Pharmacy, Poisons, Cosmetics and the Medical Devices Act 2001 to enforce the regulations and increase the frequency of the inspection visits to drug companies and retail pharmacies.

Experience has shown the poor regulation of medicines can lead to the prevalence of substandard, counterfeit, harmful and ineffective medicines on the national markets and the international commerce. The Sudanese pharmaceutical legal framework was described as one of the strictest pharmaceutical system in the region. One of the great loopholes in this system was found to be the increased number of non-registered medicines-governmental sources such as the Central Medical Supplies Public Organisation (CMSPO) and not-for-profit non-governmental Organisations (NGOs). Respondents were hopeful the double standard of rules enforcement would be lifted after the new national unity government take over, arguing the current situation in which public organisations (such as the CMSPO) sell non-registered medicines to the private pharmacies could enhance trading of counterfeit medicines and create unfair competition environment.

One of the respondent reported, “It is disturbing, in spite of the existence of appropriate legislation, illegal distribution of medicines by the CMSPO. The CMSPO continues to flourish, giving the impression the government is insensitive to harmful effect on the people of medicines distribution unlawfully, and some are of doubtful quality”. During the past three years the CMSPO started to sell unregistered medicines to the private pharmacies. The CMSPO practice (he added) will undermine the inspection and medicines control activities and ultimately jeopardise the health of the people taking medication.

Not surprisingly all respondents strongly agreed the increased number of sources of non-registered medicines will lead to entrance of low quality medicines. This result is inline with the WHO recommendation, which encourages the regulatory authorities and state members` government to register all medicines before the marketing. The medicines imported by public sector organisations are not excluded[25]. The FGDOP should define the norms, standards and specifications necessary for ensuring the safety, efficacy and quality of medicinal products. The availability, accuracy and clarity of drug information can affect the drug use decisions. The FGDOP does not have a well-developed system for pre-approval of medicines labels, promotional, and advertising materials. The terms and conditions under, which licenses to import, manufacture and distribute will be suspended, revoked or cancelled. This should be stringently applied to public, private and not-for-profit NGOs drug supplies organisations.

The predominant view, shared between the medicines’ importers is the current pharmacy legislation to some extent satisfactory and managed to prohibit the marketing of low quality medicines. The recent post-marketing study carried by the National Drug Quality Control Laboratories, suggested the power of the current regulation is overestimated[26]. The finding of this study indicates the application procedures of the current measures to ensure the quality of medicines should be revisited. The technical complexity of regulations, political, commercial and social implications, makes necessary a degree of mutual trust between concerned stakeholders ( i.e., suppliers, doctors, pharmacists, consumer representatives and government agencies ).

Conclusion and Recommendations

The study reveals the need for further research to find out how efficient the regulatory authorities at both federal and state levels are. The research also needed to discover whether or not counterfeit medicines are sold on the Sudanese market.

From the data obtained in this communication some general inferences could be made:

The brad outlines remain intact, but preventing drug smuggling across national boarders (Sudan shares frontiers with 9 countries) is hard to police.

The enforcement of the act and its regulation governing the manufacture, importation, sale, distribution and exportation of medicines are not adequate enough to control the illegal importation and sale of medicines in Sudan.

The splitting of the drug regulatory authority between two ministries and the marketing of unregistered medicines by the public drug suppliers (namely the CMSPO, and RDFs), and NGOs undermine the quality of medicines and ultimately jeopardise the health of the people taking medication.

In the light of the findings the following recommendations could be useful at various levels:

There is an urgent need for government to implement the provisions of existing Act.

The government should adequately equip and fund the National drug Analysis laboratories to start active post-marketing surveillance.

A more spirited effort need to be made by the FGDOP and the States’ Departments of Pharmacy to ensure all the medicines on the pharmacies’ shelves are registered and come from legal sources.

The states’ departments of pharmacies are not in existence should be re-established and invigorated. They should be adequately funded to be able to acquire the necessary facilities for their operations.

The CMSPO should stop importation, manufacture and distribution of unregistered medicines. It should also cease selling the tenders’ product to the private pharmacies. The latter practice undermines the inspection outcomes, because it makes inspectors task too difficult (i.e., can not identify the source of medicine whether it is CMSPO or not).

Ethical clearance and data protection consent: Before starting the data collection, ethical clearance was obtained from the Federal Ministry of Health (MOH)-Research Ethics Committee. The author signed the data protection consent and the respondents were informed it was an anonymous questionnaire and all the data collected are for the FGDOP assessment purpose. Nevertheless, the participants were also informed the data processing would not be used to support any decision-making and would not cause any damage, and distress them or to their business.

Research limitations: The selection of one group of stakeholders and ignorance of the rest (such as the CMSPO, retail pharmacies, drug manufacturers, NGOs, consumers organisations, policy-makers, regulators, police, customs, doctors, other health care professionals, and health professional unions, etc.) were not included. This means great caution must be exercised in any extrapolation to a country level statistical analysis, and percentage given must be regarded as rough estimates. The information necessary to conduct this evaluation was collected from 30 pharmacists working with medicines’ importing companies.

Reliability and validity of the research instrument: The sample chosen is indicative rather than fully representative and has been sized to be feasible in the time and resources available for the author. However, the sample is thought to be sufficient to allow valid statistical analysis. Establishing the reliability and validity of measures are important for assessing their quality[7]. The mentioned time, and resources constraints did not allow the authors to test the reliability and validity of the research instrument.

References

- 1. Ministry of Health (MOH). 2001. Act 2001: Pharmacy, Poisons, Cosmetic and Medical Devices. Ministry of Health (MOH): Sudan.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 2. Alubo, S.O.. Death for sale: A study of drug poisoning and deaths in Nigeria. (1994) Social Science & Medicine 38(1): 97 – 103.

- 3. Andalo, D. Counterfeit drugs set alarm bells ringing.(2004) Pharmaceutical Journal 273(7316): 341.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 4. Bryman, A.. Social Research Method. (2004) 2nd Edition Oxford Uni Pr: 592.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 5. Elfadil, A.A.. Quality assurance and quality control in the CMSPO. (2005)

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 6. Erhun, W.O., Babalola, O.O., Erhun, M.O.Drug regulation and control in Nigeria:The Challenge of counterfeit drugs.(2001) Journal of Health and Population Developing Countries 4(2): 23– 34.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 7. Gamal, K.A., Abdelrahman, M., Omer, A. M.. A prescription for improvement: A short survey to identify reasons behind public sector pharmacists’ migration. (2006) World Health Popul8(3): 77-92.

- 8. Helling-Borda, M. The role and experience of the World Health Organisation in assisting countries to develop and implement national drug policies.(1995) Australian Prescriber 20 (1): 34–38.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 9. Jallow, M. Evaluation of national drug policy in the Gambia, with special emphasis on the essential drug programme. (1991) University of Oslo: Norway.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 10. Lexchin, J.. Drug makers and drug regulators: Too close for comfort. A study of the Canadian situation. (1990) Soc Sci Med 31(11): 1257 – 1263.

- 11. Lofgren, H., Boer, R. Pharmaceuticals in Australia: developments in regulation and governance. (2004) Social Science and Medicine 58(12): 2397 – 2407.

- 12. 25 years Pharmacy Strategy (2002-2027). (2003) Khartoum: Sudan. Unpublished Report.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 13. National Drug Policy (NDP). (1997) Ministry of Health (MOH): Sudan.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 14. Osibo, O.O. Faking and counterfeiting of drugs. (1998) West African J of Phar 12(1): 53 – 57.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 15. Ratanwijitrasin, S., Soumerai, S.B., Weerasuriya, K.. Do national medicinal drug policies and essential drug programmes improve drug use? A review of experiences in developing countries. (2001) Soc Sci Med 53(7): 831–844.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 16. Rudolf, P. M., Bernstein, I.B.. Counterfeit Drugs. (2004) N Engl J Med 350(14): 1384 - 1386.

- 17. Shakoor, O., Taylor, R.B., Behrens, R.H.. Assessment of the substandard drugs in developing countries. (1997) Trop Med Int Health 2(9): 839 – 845.

- 18. Sibanda, F.K.. Regulatory excess: The role of regulatory impact assessment and the Competition Commission. (2004) Uni Stellenbosch.Cape Town: 1-22.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 19. Counterfeit drugs: guidelines for the development of measures to combat counterfeit drug. (1999) World Health Organisation. WHO/EDM/QSM/99.1.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 20.Comparative analysis of international drug policies. Report from the second workshop Geneva, 10-13 June 1996. (1996) (WHO/DAP).

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 21. WHO International drug policies.(2000): Geneva Switzerland14(1): 81.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 22. V. Velpandian., Elangovan, S., Naansi Agnes, L., et al.. Clinical Evaluation of Justicia tranquebariensis L. In the Management of Bronchial Asthma. (2014) AJPCT (2)9: 1103-1111.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 23. Ravi, S.K., Ratna, N.S.K., Kiranmayi, G.V.N. In vitro Study of Antioxidant and Antimalarial Activities of New Chromeno-Pyrano-Chromene Derivative. (2014) AJPCT (2)10: 1169-1176.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 24. Ramprabhu, R., Jairam, A., Karthik, K., et al. Evaluation of Regular Teat Sanitisation Control Measures for Prevention of Sub Clinical Mastitis in Cattle. (2014) AJPCT (2)10: 1212-1216.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 25. Abdeen M.O. The impact of the pharmaceutical regulations on the quality of medicines on the Sudanese market: importers’ perspective. (2015) ARC 1(2): 21-31.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

- 26. Abdeen M.O. Regulatory privatisation, social welfare services and its alternatives. (2013) Advances Med Bio 72: 69-86.

Pubmed||Crossref||Others