Decreased Visual P3 Event-Related Potential For Drug Cues In The Right Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Of Crack-Cocaine Users

Affiliation

Laboratory of Cognitive Sciences and Neuropsychopharmacology, Federal University of Espirito Santo, Vitoria-ES, Brazil

Corresponding Author

Catarine Lima Conti, PhD in Physiological Sciences Health Sciences Center, Federal University of Espirito Santo, Av. Marshal Fields, 1468, 29.047-105 Vitória-ES, Brazil. Fax: +55-27-3335-7330; Tel: +55-27-3335-7337; E-mail: catarineconti@hotmail.com

Citation

Citation: Conti, C. L., et al. Decreased Visual P3 Event-Related Potential For Drug Cues In The Right Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Of Crack-Cocaine Users. (2015) J Addict Depend 1(1): 1-4.

Copy rights

©2015 Conti, C. L. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Crack-cocaine-users; Crack dependence

Abstract

This was an exploratory open trial in which young crack-cocaine-users and non-users were clinically examined. The participant’s right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activity was analysed by an event-related potentials procedure under a cue-reactivity paradigm. The patients group exhibited lower frontal executive scores. Accordingly, they exhibited lower right DLPFC activity for crack cues when compared with neutral cues while healthy subjects exhibited the opposite effect. Considering that the right DLPFC has an important role in executive functions, which is usually impaired in drug addicts, we suggest that any intervention that can improve its activity may have beneficial effects in drug dependence treatment.

Introduction

Crack-cocaine is a highly devastating drug. Its cerebral effects are immediate, intense and fleeting, leading to compulsive use and increasing the risk of abuse and dependence. These dependents are routinely observed to have difficulties adhering to treatment, and the underlying abnormalities in the neural mechanisms of these patients are increasingly been studied.

Crack dependence is associated with structural and functional damage to prefrontal cortex[1]. Frontal lobe volume damage has been identified in subjects that are alcoholic[2-4], heroin-dependent[5] and cocaine-dependent[6,7]. This frontal area is broadly related to executive functions and to the brain’s reward circuitry[8-10]. Once this frontal area is impaired in drug users, the cognitive ability to regulate drug-seeking behaviour is decreased and the risk of dependence is increased.

The Event-Related Potential (ERP) has emerged as an important technique to study the cognitive potentials underlying the presentation of a stimulus (i.e.,cue) [11,12]. Experimental investigations of addictive phenomena using a cue-reactivity paradigm have been performed extensively[13-17]. One of the most studied endogenous ERP components is the P3 wave, which is the largest positive-going peak occurring within a time window generally between 250-600 ms. The P3 wave is typically observed in more anterior brain areas[18] and it is sensitive to general and specific arousal effects that contribute to attention activation and information processing[19]. The P3 wave is also related to updating internal models about context and environment, which is triggered by event-related changes reflecting self-motion, supporting the view that cognition may be tightly interlocked with motor activity[19-21]. This link between cognition and motor activity is relevant since patients with substance abuse disorder show cognitive deficits that could affect normal behavioural response before the drug.

A growing amount of evidence suggests that electroencephalographic activity of cocaine users is increased in several cerebral areas while is diminished in others in different situations[22]. These areas involve those related with craving and executive functions. Here, we examined the electrophysiological activity of right DLPFC of crack-cocaine abusers during the cue-reactivity paradigm. All data were replied with healthy control subjects.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

This study included eighteen male participants: nine male crack-cocaine users (aged 30.4 ± 5.6 SD) and nine healthy male control subjects (aged 25.2 ± 4.2 SD). Substance abuse patients, as defined by the DSM-IV, were consecutively recruited from the Center for Psychosocial Care for treatment of crack dependence syndrome in Espirito Santo, Brazil.

Treatment and data collection were conducted according to the ethical principles in the Declaration of Helsinki, which are equivalent to those established by the Ethics Committee for Research at the Center of Health Sciences, Federal University of Espirito Santo, Brazil. This study is part of a project approved by this ethics committee under registration 296/10 and is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under the identifier NCT01337297.

General Procedures

Subjects were fully informed about the experimental protocol and voluntarily signed an informed consent form. The experimental protocol consisted of a clinical examination that included the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) followed by ERP recording during the random visual presentation of three crack-related images and three neutral images.

Frontal Function Assessment

The Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB), developed by Dubois et al[23]. was used to explore the following six different domains of executive function: 1) conceptualisation 2) mental flexibility 3) motor programming 4) sensitivity to interference 5) inhibitory control and 6) autonomy. Each of these items is scored from 0 (zero) to a maximum of 3. Thus, the maximum score of FAB is 18. A trained examiner administered this assessment.

Event-Related Potential (ERP)

The recordings were made during the presentation of visual stimuli (i.e., cues) related to the consumption of crack-cocaine (e.g., crack rocks, pipes or paraphernalia used for substance use, and someone inhaling the substance) or neutral images that were unrelated to the consumption of crack-cocaine (e.g., landscape, flowers, butterfly). Within each category (crack-related vs. neutral), the three types of images were presented 45 times, 15 presentations of each image of the same class were randomly shown. Subjects were not asked to evoke motor response (like pressing the button) but rather they were only visualizing the pictures. Considering the two categories of images, there were 90 visual presentations. Each image was presented for 1000 ms, at intervals of 2000 ms. The entire procedure lasted 4.5 minutes. For the analysis, the P3 ERP component from 350 to 600 ms of these 90 presentations was averaged (a 200 ms pre-stimulus period served as the baseline).

With a monitor placed in front of the subject, a computer ran a program (Presentation, Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc, Albany, CA) that enabled the analysis of the averaged evoked waves under each type of visual stimulus. The electrophysiological recording was obtained through a 32-channel system (frequency filter: 0.016-1000 Hz; sample rate: 1000 Hz; ground: AFz; the average of mastoids as reference; analogue pass band of 1–10 Hz) with active electrodes (actiCAP BP; Brain Products Ltd, Munich, Germany) at locations based on the International 10/20 system.

Data Processing

All EEG data were processed using Brain Vision Analyzer 2.0 Professional (Brain Products Ltd, Munich, Germany). Low-resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (LORETA) was applied to estimate the three-dimensional intra cerebral current density distribution (μA/mm²). The region of interest (ROI) included Brodmann areas 9 and 46, corresponding to the right side of the DLPFC.

Statistical Analyses

Data were presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD). The mean amplitude of P3 ERP component was analyzed via a non-parametric unpaired test, the Mann-Whitney test, as the activity (current density) did not fulfill the criteria for normality. A p-value < 0.0001 was considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) was employed for statistical analyses and graphic presentations.

Results

The sample of crack-cocaine users consisted of subjects with 5.3 ± 2.7 years of drug use and no more than one month of abstinence (13 ± 10.3 days). When compared with healthy subjects, the patients presented lower FAB scores (11.9 ± 3.5 vs. 15.4 ± 1.3; p < 0.05; independent t-test), indicating that drug use may be associated with frontal lobe dysfunction.

P3 ERP Component - Difference Between Crack-Related and Neutral Images

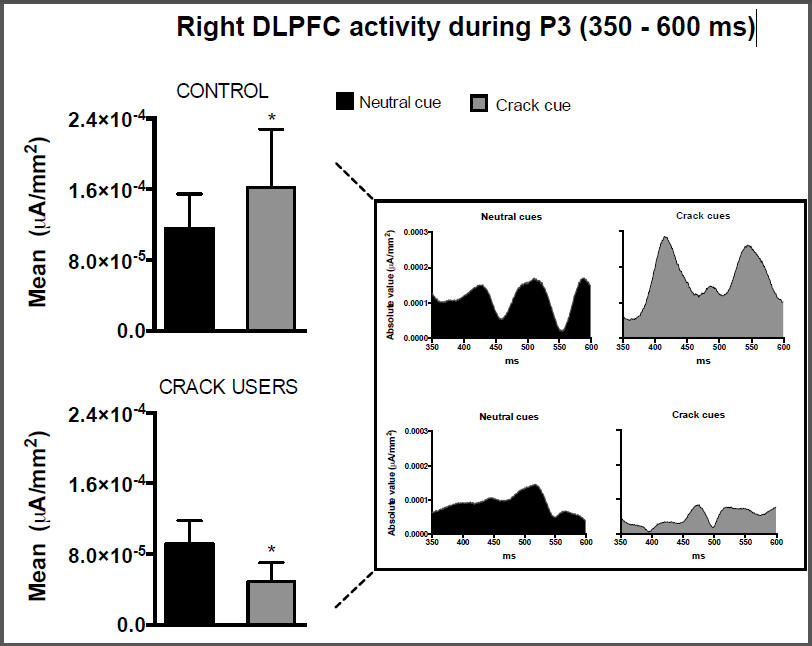

The EEG recorded during the drug cue reactivity paradigm evidenced that the activity of the right DLPFC during the visualization of crack cues was significantly lower (p < 0.0001) than this ROI activity during the visualization of neutral cues in the crack dependents group. Controversially, the activity of the right DLPFC during the visualization of crack cues was significantly higher (p < 0.0001) when compared with neutral cues in the control group.

Figure 1: Current density in the P3 segment (350 – 600 ms) elicited by neutral or crack-related cue presentations in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (right DLPFC). Data are represented for healthy subjects (control, N = 9) and crack users (N = 9). *p < 0.0001; Mann-Whitney test comparing neutral vs. crack cues in each group; mean ± SD.

Discussion

Here we observed that young male crack-cocaine users exhibited lower frontal executive scores when compared to gender and age-matched healthy subjects. Concurrently, we observed that crack-cocaine users are more likely to show lower brain activity during P3 ERP component in the right DLPFC when processing crack-related images.

Though the spatial resolution is low, ERPs have an excellent temporal resolution, making this method ideally suited to investigate the time-course of emotional processing and drug cue reactivity. Importantly, neural generators of the ERP components invoke cortical regions that play an integral part in the cycle of drug addiction[24]. The P3 component is probably the most widely used ERP measurement in psychiatric and other clinical applications, and its amplitude has been considered to indicate the allocation of attentional resources[19,25].

Cocaine dependence has been frequently associated with low activation in the frontal, parietal and temporal cortical regions, especially during conditions requiring high cognitive control, such as in decision making[26]. Such conditions may lead individuals to develop increased risk for addictive behaviours. This cerebral hypofunction involving substantial cortical frontal dysfunction has been strongly correlated with drug addiction [for review see 24].

Cognitive dysfunction induced by psychostimulants has been related to low activation in the prefrontal cortical area[27] and reduced prefrontal cortical volume[1]. Once the prefrontal cortex has extensive connections with mesolimbic structures, any prefrontal dysfunction is usually associated with additional changes in subcortical area[28]. Cocaine abusers that are abstinent for one week to several months had significantly lower values of D2 binding in the striatum when compared to normal subjects, and this D2 deficiency was correlated with decreased metabolism in the frontal lobes region[29,30]. Dysfunction in cortical-subcortical circuits seems to be related to the difficulty of ceasing drug use because of the loss in the ability to control and inhibit prepotent responses due to craving in addiction[7].

The association between P3 amplitude and cue-reactivity has been described in volunteers with a history of cocaine use[31,32] and other drug use[33,34]. These studies report increased craving after the presentation of drug-related cues, as well as an increased P3 amplitude. Significantly higher amplitudes in ERPs were also found after the presentation of alcohol-related words when compared to words unrelated to alcohol in alcohol-dependent patients but not in non-alcoholic controls[35,36]. Our present data is controversial, and one possibility is that most protocols using this paradigm ask for subjects to press some button while they are visualizing the target picture. Here, the subjects were not asked to evoke motor response, rather, they were only observing the images. This is a key point that needs to be more investigated. For now, we suggest a different recording profile task-dependent. The authors agree that the number of subjects involved in this preliminary study is relatively low and, though the relevant result, this is a limitation in the full interpretation of these data.

Conclusion

This was an exploratory study showing that in addition to a clinical frontal lobe hypofunction observed in crack-cocaine users, electrophysiological data indicate a lower right DLPFC activity.

Recommendations

Considering that the DLPFC has an important role in executive functions, which is usually impaired in drug addicts, we suggest that any intervention that can improve its activity may have beneficial effects in drug dependence treatment and this protocol can be used as a parameter of evaluation.

Declaration Of Interest: This research was funded by CAPES governmental agency. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Fein, G., Sclafani, V.Di., Meyerhoff, D.J. Prefrontal cortical volume reduction associated with frontal cortex function deficit in 6-week abstinent crack-cocaine dependent men. (2002) Drug Alcohol Depend 68(1): 87- 93.

- 2. Moselhy, H.F., Georgiou, G., Kahn, A. Frontal lobe changes in alcoholism: a review of the literature. (2001) Alcohol Alcohol 36(5): 357- 368.

- 3. Kril, J.J., et al. The cerebral cortex is damaged in chronic alcoholics. (1997) Neuroscience 79(4): 983- 998.

- 4. Pfefferbaum, A., et al. Frontal lobe volume loss observed with magnetic resonance imaging in older chronic alcoholics. (1997) Alcohol Clin Exp Res 21(3): 521- 529.

- 5. Liu, H., et al. Frontal and cingulate gray matter volume reduction in heroin dependence: optimized voxel-based morphometry. (2009) Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 63(4): 563- 568.

- 6. Franklin, T.R., et al. Decreased gray matter concentration in the insular, orbitofrontal, cingulate, and temporal cortices of cocaine patients. (2002) Biol Psychiatry 51(2): 134- 142.

- 7. Goldstein, RZ., Volkow, N.D. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. (2002) Am J Psychiatry 159(10): 1642- 1652.

- 8. Hyman, S.E., Malenka, R.C., Nestler, E.J. Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory. (2006) Annu Rev Neurosci 29: 565- 598.

- 9. Fuster, J.M. Executive frontal functions. (2000) Exp Brain Res 133(1): 66- 70.

- 10. D'Esposito, M., et al. The neural basis of the central executive system of working memory. (1995) Nature 378(6554): 279- 281.

- 11. Picton, T.W., et al. Guidelines for using human event-related potentials to study cognition: recording standards and publication criteria. (2000) Psychophysiology 37(2): 127- 152.

- 12. Brandeis, D., Lehmann, D. Event-related potentials of the brain and cognitive processes: approaches and applications. (1986) Neuropsychologia 24(1): 151- 168.

- 13. Hester, R., Dixon, V., Garavan, H. A consistent attentional bias for drug-related material in active cocaine users across word and picture versions of the emotional Stroop task. (2006) Drug Alcohol Depend 81(3): 251- 257.

- 14. Sokhadze, E., et al. Attentional Bias to Drug- and Stress-Related Pictorial Cues in Cocaine Addiction Comorbid with PTSD. (2008) J Neurother 12(4): 205- 225.

- 15. Carter, B.L., Tiffany, S.T. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. (1999) Addiction 94(3): 327-340.

- 16. Modesto-Lowe, V., Kranzler, H.R. Using cue reactivity to evaluate medications for treatment of cocaine dependence: a critical review. (1999) Addiction 94(11): 1639- 1651.

- 17. Herning, R.I., Glover, B.J., Guo, X. Effects of cocaine on P3B in cocaine abusers. (1994) Neuropsychobiology 30(2-3): 132- 142.

- 18. Katayama, J., Polich, J. Stimulus context determines P3a and P3b. (1998) Psychophysiology 35(1): 23- 33.

- 19. Polich, J. Updating P300: an integrative theory of P3a and P3b. (2007) Clin Neurophysiol 118(10): 2128- 2148.

- 20. Schupp, H.T., et al. Affective picture processing: the late positive potential is modulated by motivational relevance. (2000) Psychophysiology 37(2): 257- 261.

- 21. Dunning, J.P., et al. Motivated attention to cocaine and emotional cues in abstinent and current cocaine users-an ERP study. (2011) Eur J Neurosci 33(9): 1716- 1723.

- 22. Volkow, N., Li, T.K. The neuroscience of addiction. (2005) Nat Neurosci 8(11): 1429- 1430.

- 23. Dubois, B., et al. The FAB: a Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside. (2000) Neurology 55(11): 1621- 1626.

- 24. Goldstein, R.Z.,Volkow, N.D. Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. (2011) Nat Rev Neurosci 12(11): 652- 669.

- 25. Polich, J., McIsaac, H.K. Comparison of auditory P300 habituation from active and passive conditions. (1994) Int J Psychophysiol 17(1): 25- 34.

- 26. Barros-Loscertales, A., et al. Lower activation in the right frontoparietal network during a counting Stroop task in a cocaine-dependent group. (2011) Psychiatry Res 194(2): 111- 118.

- 27. Nestor, L.J., et al. Prefrontal hypoactivation during cognitive control in early abstinent methamphetamine-dependent subjects. (2011) Psychiatry Res 194(3): 287- 295.

- 28. Barros-Loscertales, A., et al. Reduced striatal volume in cocaine-dependent patients. (2011) Neuroimage 56(3): 1021- 1026.

- 29. Volkow, N.D., et al. Decreased dopamine D2 receptor availability is associated with reduced frontal metabolism in cocaine abusers. (1993) Synapse 14(2): 169- 177.

- 30. Volkow, N.D., et al. Effects of chronic cocaine abuse on postsynaptic dopamine receptors. (1990) Am J Psychiatry 147(6): 719- 724.

- 31. Franken, I.H., et al. Two new neurophysiological indices of cocaine craving: evoked brain potentials and cue modulated startle reflex. (2004) J Psychopharmacol 18(4): 544- 552.

- 32. Grant, S., et al. Activation of memory circuits during cue-elicited cocaine craving. (1996) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93(21): 12040- 12045.

- 33. Littel, M., Franken, I.H. The effects of prolonged abstinence on the processing of smoking cues: an ERP study among smokers, ex-smokers and never-smokers. (2007) J Psychopharmacol 21(8): 873- 882.

- 34. Namkoong, K., et al. Increased P3 amplitudes induced by alcohol-related pictures in patients with alcohol dependence. (2004) Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28(9): 1317- 1323.

- 35. Bartholow, B.D., Henry. E.A., Lust, S.A. Effects of alcohol sensitivity on P3 event-related potential reactivity to alcohol cues. (2007) Psychol Addict Behav 21(4): 555- 563.

- 36. Herrmann, M.J., et al. Event-related potentials and cue-reactivity in alcoholism. (2000) Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24(11): 1724- 1729.