Determining Underground Mining Work Postures Using Motion Capture and Digital Human Modeling

Joseph P. DuCarme, Adam K. Smith, Dean Ambrose

Affiliation

Mine Safety and Health Research, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Pittsburgh, USA

Corresponding Author

Timothy J. Lutz, Mechanical Engineer, DHHS/CDC/NIOSH/PMRD, 626 Cochrans Mill Rd, Pittsburgh PA15236, Tel: +1-412-386-4904; E-mail: tlutz@cdc.gov

Citation

Lutz, T.J., et al. Determining Underground Mining Work Postures Using Motion Capture and Digital Human Modeling. (2016) J Environ Health Sci 2(6): 1-6.

Copy rights

© 2016 Lutz, T.J. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Mine safety; Posture identification; Motion capture; Underground coal; Proximity detection

Abstract

According to Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) data, during 2008-2012 in the U.S., there were, on average, 65 lost-time accidents per year during routine mining and maintenance activities involving remote-controlled continuous mining machines (CMMs). To address this problem, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) is currently investigating the implementation and integration of existing and emerging technologies in underground mines to provide automated, intelligent proximity detection (iPD) devices on CMMs. One research goal of NIOSH is to enhance the proximity detection system by improving its capability to track and determine identity, position, and posture of multiple workers, and to selectively disable machine functions to keep workers and machine operators safe. Posture of the miner can determine the safe working distance from a CMM by way of the variation in the proximity detection magnetic field. NIOSH collected and analyzed motion capture data and calculated joint angles of the back, hips, and knees from various postures on 12 human subjects. The results of the analysis suggests that lower body postures can be identified by observing the changes in joint angles of the right hip, left hip, right knee, and left knee.

Introduction

Coal mining is a relatively dangerous industry compared to private industry[1], but is a key component to the national energy strategy[2]. One of the primary pieces of equipment used during underground coal production is the continuous mining machine (CMM). These machines are operated by remote control, and are used to extract coal from the working face through a rotary cutting drum and onboard articulating conveyor. Since 1984, there have been 39 fatalities involving striking and pinning of the operator and other workers by the CMM[3] and according to MSHA (Mine Safety and Health Administration) data, during 2008 - 2012 in the U.S., there were, on average, 65 lost-time accidents per year during routine mining and maintenance activities on CMMs.

In recent years technologies have been developed to reduce injuries and fatalities associated with CMM operation. Proximity detection systems warn and disable the machine if the operator intrudes into an unsafe area[4,5]. Recently, further advances have been made through triangulating operator position and only disabling machine motions that are hazardous[6,7,8]. To improve the accuracy and performance, information about worker posture could be used by CMM proximity detection systems.

The mining process requires workers to change posture and position based on several factors such as roof height, machinery location, and mine ventilation. Previous studies have addressed worker positioning around the CMM rather than posture[9,10]. Some investigations unrelated to mining have focused on wireless and embedded sensor technology to determine human posture[11-14]. However, these studies were ultimately concerned with human position in specific postures. Further research is needed to identify underground worker postures, and determine the transition between them. Through examination and understanding of key reference joint angles, underground mine worker posture can be analyzed and determined.

Methods

Posture identification research was in the feasibility stage so rather than using actual miners, twelve Federal employees at the Bruceton, PA location of NIOSH volunteered to be subjects. None of the subjects were specifically involved with posture identification research. Prior to developing the protocol, researchers conducted preliminary tests that helped them to dewww sign the experiment, develop test procedures, and preliminarily determine which of the subjects’ changes in angles of the back, hips, and knees could be used to identify the posture. The protocol was approved by the NIOSH Human Subjects Review Board and all subjects were required to sign an informed consent.

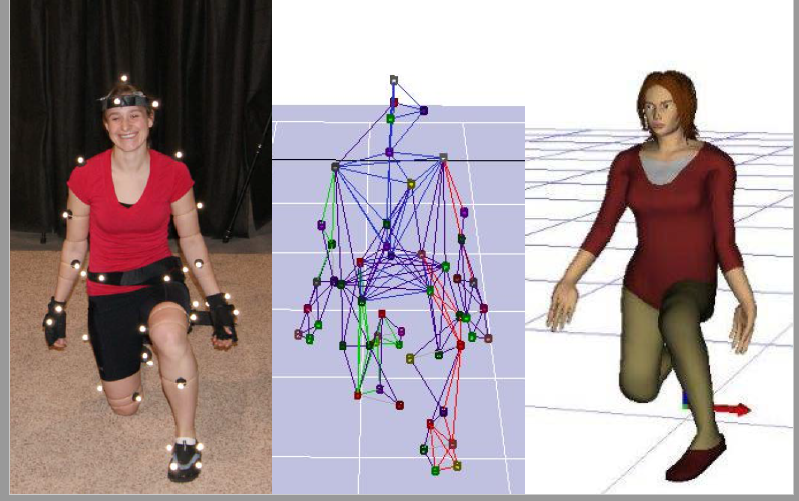

subjects were required to sign an informed consent. Posture data was collected from 12 human subjects (7 male and 5 female) using motion capture hardware and software (Cortex, Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Rosa CA). This motion capture system uses an array of reflective markers placed on the subject and other items of interest. The array of markers used in this testing was the JACK marker set[15] that enable use with Jack® (Tecnomatix JACK, Siemens USA, Washington DC), Siemens’s 3D digital human modeling/simulation software. The Jack® software enabled analysis of the data for determining accurate body joint angles of interest on each subject tested. Figure 1 is an example of a human subject in pose and the corresponding motion capture and Jack simulation.

Figure 1: Human subject, motion capture, and Jack software simulation displays.

The subjects were asked to assume eight different postures: walking, standing, sitting with bent knees, sitting with legs straight, kneeling on left knee, kneeling on both knees, kneeling on right knee, and lying down. These were selected from previous research[16] where interviews conducted with CMM operators detailed their typical working postures. The order in which subjects were instructed to assume the postures was randomized so that subjects were unable to anticipate what the next posture would be. Subjects were instructed to assume the postures in the manner most natural to them. Subjects were tested 24 times in each posture, and data was captured at a rate of 30 frames per second. Upon completion of data collection, researchers reviewed the data for each subject and selected the portion of each test in which the subject was static, in other words, keeping still in a given posture in contrast to changing from one posture to the next. A set of data for each subject in each posture was constructed by merging the static portions from the 24 tests of the given posture.

Measurement and Analysis

Each subject provided joint angle data while standing, kneeling on the right knee, left knee, and both knees, sitting with legs bent, sitting with both legs extended, and lying on the left side. Human subjects were instructed to assume the position in their own natural way. No specific instructions were given on how to get into the position or exactly how the participants’ legs should be positioned. Playing back motion capture data on each subject on Jack digital human software enabled selection of a time frame for when each posture tested started and ended. As each posture time frame was found, the appropriate body joint angle data was collected and sorted for each of the 12 subjects. The shape of the distribution, statistical dispersion, and central tendency were obtained from the descriptive statistics.

The data for each of the 12 subjects was sorted into groups: Female, Male, and Gender-All and according to the subjects’ height, weight, and age (Table 1). Heights in inches were separated into four sets: 64, 66, 70-71, and 73-74. Weights in pounds were separated into five sets: 125-135, 170, 180-185, 200-205, and 210-220. Ages in years were separated into three sets: 25-26-30-32, 45-47-48, and 55-56. Height, weight, and age sets were constructed according to how their units clustered.

Table 1: Database assembled into Groups and Subgroups.

| Group | Sub Group | Number of Subjects |

|---|---|---|

| Female | - | 5 |

| Male | - | 7 |

| Combined gender | all 12 subjects | |

| Height-inches | 64 | 2 |

| 66 | 3 | |

| 70 - 71(1) | 5 | |

| 73 - 74 | 2 | |

| Weight- pounds | 125- 135 | 2 |

| 170 | 2 | |

| 180(2) - 182 - 185 | 4 | |

| 200 - 205 | 2 | |

| 210 - 220 | 2 | |

| Age- Years | 25 - 26 - 30 - 32 | 4 |

| 45 - 47 - 48 | 3 | |

| 55(3) - 56(2) | 5 |

Researchers also generated data sets of descriptive statistics on each group. This statistical data was used to calculate an estimate of central tendency statistics for each posture and related body joints: back, right hip, left hip, right knee, and left knee. The median was used as a measure of central tendency, because the data was not normally distributed. In the case of the median on how widely values are dispersed, the measure of the inter quartile range (IQR) is used.

Upon inspection of the data, it was found that the mean was not suitable to be used in a skewed distribution to determine joint angles. Because of the median’s ability to ignore outlying values, it is often regarded as a more robust measure, in that it is focused around the middle values and ignores extreme values on either side. The median is also very robust in the presence of outliers (values that differ significantly from the mean), while the mean is rather sensitive.

The skewness measure was used to indicate the level of non-symmetry within the measured joint angle data. If the distribution of the data is symmetric, then skewness will be close to 0 (zero). A negative value indicates a skew to the left and a positive value a skew to the right. The skewness of a sample is consistent with a normal distribution for a population if its absolute value is small, e.g. less than 0.3. The standard error of skewness (ses) can be estimated roughly using the following formula after Tabachnick and Fidell[17]: √ (6/N). For this research, N = 12, √ (6/12) or ses is 0.707. Values close to 2 ses or more (regardless of sign) are skewed to a significant degree.

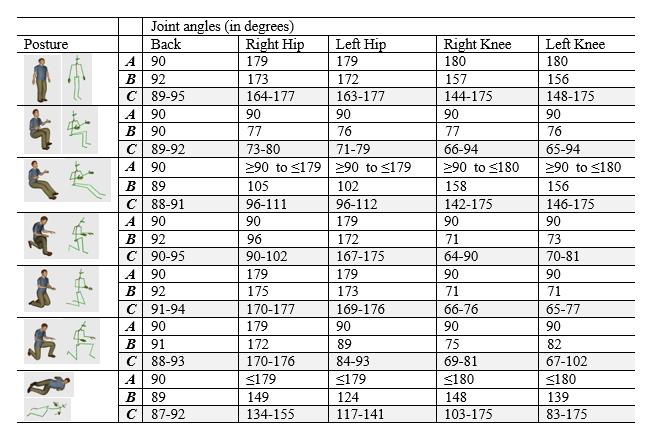

After completion of the statistical analysis, researchers developed a posture-joint angle matrix that depicts joint angles that distinguish one posture from another. Table 2 (C rows) illustrates the range joint angle values for corresponding postures. The A rows in Table 2 are the joint angles measured when a Jack human figure is placed in the corresponding posture. The postures used in this study are defined as standard postures in the Jack software. The statistical results in Table 2(B rows) show that these results are representative of the data and show similar trends as were established in the preliminary tests.

Table 2: Matrix that defines corresponding posture to ideal joint angles (A-rows), combined gender results (B-rows), and range of results for potential sensor parameters (C-rows).

Results

Walking posture data were not analyzed statically as with the other seven postures, so it is not included in the overall analysis. The skewness of all the statistical data sets showed that overall 38.1% were skewed to a significant degree (greater than 2 ses or 1.414 absolute value). The skewness of a sample is consistent with a normal distribution for a population if its value is small (< 0.3, absolute value); consequently, statistical data sets showed that overall 70.3% were skewed. Because of the skewness in the database, the median was used for the estimate of central tendency.

Hip joint angles for standing posture (right-173°, left- 172°) nearly reached the expected value of 179°. Knee joint angles for standing (right-157°, left-156°) were less than the expected value; however, the IQR was 25.3 for the right knee and 25.0 for the left knee and the Mode (most frequent value) was 175 for both knees. Standing posture data indicate that both hip and knee joint values lean towards the maximum expected value. Slouching and favoring a side will cause hip and knee joints to move away from the expected standing joint values.

The hip and knee joint data for sitting with knees bent revealed that the angles were nearly the same—respectively 77°, 76°, 77°, and 76°. Regarding sitting with both legs extended, the hip joint angles (right-105°, left-102°) were smaller than the knee joint angles (right-158°, left-156°), which is correct for this position. The knee joints in the sitting posture have similar values to knee joints in the standing posture and their interquartile range (IQR) is high, sitting with legs extended (29.6, 25.9) and standing (25.3, 25.0). The data for when subjects were sitting with both knees bent show that both hip and knee joints are nearly the same values. A slouching posture was observed in the subjects, which could have returned lower-than-expected hip joint measurements. When subjects were sitting with both legs extended, similar hip values were mirrored. Knee values lean towards the maximum expected value. During testing, observations of subjects showed that few extended their legs completely; instead, they extended their legs in a relaxed pose that caused the hip and knee angles to move away from the expected values for this posture.

The hip and knee joint values for kneeling on the left knee reflect expected values for the hips (right-96°, left-172°) and knees (right-71°, left-73°). The hip and knee joint values for kneeling on both knees reflect expected values for the hips (right-175°, left-173°) and knees (right-71°, left-71°). The hip and knee joint values for kneeling on the right knee reveal expected values for the hip (right-172°, left-89°) and knees (right-75°, left-82°). Kneeling postures show variations of joint values between the knees, making them ideal to distinguish between kneeling postures as well as other postures. Observation of subjects during kneeling postures on one knee showed that subjects leaned towards the knee that they were kneeling on. This posturing does affect hip and knee measurements, with slightly smaller values than if they were more erect in their pose.

When subjects were lying down on the left side, the hips values (right-149°, left 124°) and knees values (right-148°, left- 139°) were all high as expected and they all varied as well. The lying down posture has the highest measure of variability for hip and knee joints among the postures as reflected in the IQR for the hips (right-23.0, left-23.2) and knees (right-43.4, left-33.0).

Observation of subjects during testing revealed various leg positions when lying down, causing knee and hip measurements to vary significantly as indicated in the data. ndependent-samples t-tests were conducted to determine whether data from male and female participants should be combined or analyzed separately. First, to summarize data for individual subjects, the median, 25th percentile, and 75th percentile of joint angles were computed for each joint in each posture, respectively. Then t-tests were used to test for significant between-gender differences in average values of the three summary statistics. Out of 84 tests (7-postures x 4-joints x 3-summary statistics) there were only three significant observations. In the sitting with bent knees posture, significant differences were found in the median of right knee angles, the 75th percentile of right knee angles, and the 75th percentile of left knee angles, with the average angle for females wider than the average angle for males.

Discussion

These results can be explained by a situation that was observed during data collection for this posture. Whereas in most cases subjects sat with their backs straight and their knees in an angle close to 90 degrees, two female subjects and one male subject tended to sit in a more relaxed posture with their back bent and their knees at a wider angle. Due to this observation, it was felt that the significant results could be attributed to variation among individuals rather than to gender differences. It was decided, therefore, to combine data from male and female subjects for every joint in every posture. Table 3 shows the results of the median joint angles for individual and combined gender for the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile.

The analysis showed that the results are representative of the data, correlated well, and that change in angles of the hip and knee joints can used to distinguish postures. The analysis of combined gender data results are shown in Table 2 (B rows). Back joint data for all postures are between 92° and 89°. Because of how close the data are, back joint data is a non-factor in identifying a distinction between postures.

So that female and male subject data could be combined and acceptable for calculating statistical data sets, an independent- samples t-tests was measured. Due to the observation from the t-tests, it was felt that the significant results could be attributed to variation among individuals rather than to gender differences. It was decided, therefore, to combine data from male and female subjects for every joint in every posture. Kneeling postures show variations of values between the knees, making these values ideal to distinguish between other postures. Sitting postures and the standing posture have trends in their data that favor expected values for good posture identification. The lying down posture is unique in that all hip and knee joint values are relatively high and can be used to distinguish between sitting and kneeling postures. The one exception is that when comparing lying down to standing the knee joint data may overlap, making it difficult to distinguish between the postures. Analysis determined that the results are representative of the data and confirmed similar data trends as established from the preliminary test results.

Table 3: Median joint angles for individual and combined gender for 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile.

| Posture | Gender | Right Hip | Left Hip | Right Knee | Left Knee | ||||||||

| P25 | P50 | P75 | P25 | P50 | P75 | P25 | P50 | P75 | P25 | P50 | P75 | ||

| Stand | Male | 168 | 171 | 175 | 168 | 172 | 174 | 155 | 158 | 162 | 155 | 158 | 161 |

| Female | 168 | 174 | 176 | 167 | 172 | 174 | 163 | 164 | 164 | 164 | 164 | 165 | |

| Both | 168 | 172 | 175 | 168 | 172 | 174 | 159 | 161 | 163 | 159 | 160 | 163 | |

| Sit bent knees | Male | 72 | 75 | 78 | 72 | 74 | 77 | 72 | 75 | 81 | 72 | 76 | 81 |

| Female | 76 | 79 | 84 | 73 | 78 | 84 | 81 | 93 | 103 | 79 | 91 | 101 | |

| Both | 74 | 77 | 81 | 72 | 76 | 80 | 76 | 83 | 90 | 75 | 82 | 89 | |

| Sit straight legs | Male | 99 | 103 | 106 | 99 | 102 | 105 | 155 | 158 | 160 | 155 | 158 | 161 |

| Female | 103 | 105 | 109 | 102 | 105 | 108 | 161 | 164 | 164 | 162 | 164 | 165 | |

| Both | 101 | 104 | 107 | 100 | 103 | 106 | 157 | 160 | 162 | 158 | 161 | 163 | |

| Kneel left knee | Male | 91 | 97 | 103 | 157 | 165 | 174 | 67 | 81 | 86 | 68 | 79 | 86 |

| Female | 95 | 98 | 103 | 167 | 173 | 176 | 73 | 81 | 90 | 74 | 77 | 82 | |

| Both | 93 | 97 | 103 | 161 | 169 | 175 | 69 | 81 | 88 | 71 | 78 | 84 | |

| Kneel both knees | Male | 168 | 174 | 177 | 169 | 172 | 176 | 69 | 72 | 74 | 67 | 70 | 73 |

| Female | 168 | 175 | 178 | 168 | 174 | 177 | 71 | 74 | 77 | 72 | 75 | 79 | |

| Both | 168 | 174 | 177 | 168 | 173 | 176 | 69 | 72 | 75 | 69 | 72 | 75 | |

| Kneel right knee | Male | 167 | 173 | 176 | 85 | 88 | 91 | 72 | 76 | 79 | 76 | 79 | 84 |

| Female | 166 | 171 | 174 | 87 | 92 | 95 | 73 | 76 | 79 | 85 | 89 | 94 | |

| Both | 167 | 172 | 175 | 86 | 90 | 93 | 72 | 76 | 79 | 80 | 83 | 88 | |

| Lying down | Male | 144 | 150 | 155 | 120 | 125 | 132 | 142 | 149 | 154 | 126 | 130 | 140 |

| Female | 145 | 150 | 157 | 126 | 131 | 137 | 138 | 142 | 148 | 143 | 146 | 149 | |

| Both | 144 | 150 | 156 | 122 | 127 | 134 | 140 | 146 | 152 | 133 | 137 | 144 | |

Conclusion

A range of values (minimums and maximums) by posture and individual body joint were obtained by sorting and arranging each median data set from each category (Female, Male, and Genders Combined; Heights, Weights, and Ages). This information was used to determine which body joints are needed to determine a specific posture used by workers during operation of CMMs in underground coal mines. The body joints of the back, hips, and knees can be used to predict whether a CMM operator is standing, sitting with knees bent, sitting with both legs extended, kneeling on the left knee, both knees, right knee, and lying done on the left side. More research would be needed to determine posture values using actual miners and postures associated with other work tasks that are performed on or around a CMM, such as maintenance.

Results from the analysis revealed that it is feasible for postures to be identified by obtaining the values of the joint angles of the right hip, left hip, right knee, and left knee. In addition, posture joint values could be used to select person-wearable sensors for posture identification of CMM operators in underground coal mines. Implementing sensors of this type into safety devices such as proximity detection systems could reduce fatalities and injuries in which a person is struck or pinned by underground machinery such as a CMM.

Acknowledge:

The authors gratefully acknowledge assistance from Emily Burger, Jacob Carr, and Gail McConnell in conducting these studies. The authors also acknowledge the assistance from Elaine Rubenstein in the data analysis.

Disclaimers:

Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by NIOSH. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

References

- 1. Fact Sheet, Coal Mining, Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities in the Coal Mining Industry. (2010) Bureau of Labor and Statistics

- 2. Annual Energy Outlook 2014. Energy Information Administration.

- 3. Huntley, C. Remote Controlled Continuous Mining Machine Fatal Accident Analysis Report of Victim’s Physical Location with Respect to the Machine. (2013) U.S. Department of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration.

- 4. Schiffbauer, W. Active Proximity Warning System for Surface and Underground Mining Applications. (2002) Mining Engineering.

- 5. DuCarme, J.P., Carr, J.L., Reyes, M.A. Smart Sensing: The Next Generation in Proximity Detection. (2013) Mining Magazine 58-66.

- 6. Carr, J.L., DuCarme, J.P. Performance of an Intelligent Proximity Detection System for Continuous Mining Machines. (2013) SME Annual Meeting, Denver, CO.

- 7. Jobes, C.C., Carr, J.L., DuCarme, J.P. Evaluation of an Advanced Proximity Detection System for Continuous Mining Machines. (2012) Intl J Applied Eng Res 7(6): 649-671.

- 8. Carr, J.L., Reyes, M.A., Lutz, T. Underground field evaluations of proximity detection technology on continuous mining machines. (2014) SME Annual Meeting, Salt Lake City, UT.

- 9. Bartels, J.R., Ambrose, D.H., Gallagher, S. Analyzing factors influencing struck-by accidents of a moving mining machine by using motion capture and DHM simulations. (2008) Digital Human Modeling for Design and Engineering Conference and Exhibition, Pittsburgh, PA, United states, SAE International.

- 10. Bartels, J.R., Ambrose, D.H., Gallagher, S. Effect of operator position on the incidence of continuous mining machine/worker collisions. (2007) 51st Annual Meeting of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, HFES Baltimore, MD, Human Factors an Ergonomics Society Inc.

- 11. Johansson, R., Magnusson, M., Akesson, M. Identification of human postural dynamics. (1988) IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 35(10): 858-869.

- 12. Wong, W.Y., Wong, M.S. Detecting spinal posture change in sitting positions with tri-axial accelerometers. (2008) Gait Posture 27(1): 168-171.

- 13. Biswas, S., Quwaider, M. Remote monitoring of soldier safety through body posture identification using wearable sensor networks. (2008) Proceedings of SPIE Defense and Security Symposium, International Society for Optics and Photonics 6980(69800G-2): 1-12.

- 14. Xu, M., et al. Towards accelerometry based static posture identification. (2011) Consumer Communications and Networking Conference (CCNC), IEEE.

- 15. Ducarme, J.H., Kwitowski, A.J. Mine roof bolting machine safety: investigations of roof bolter boom swing velocity. (2010) Pittsburgh, PA. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Oiccupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSJ) 1-35.

- 16. Bartels, J.R., Gallagher, S., Ambrose, D.H. Continuous Mining: A Pilot Study of the Role of Visual Attention Locations and Work Position in Underground Coal Mines. (2009) Prof Saf 54(8): 28–35.

- 17. Tabachnick, B.G., Fidell, L.S. Using multivariate statistics. (1996) ISBN 0673994147, 3rd Edition, Harpers Collins College Publishers, New York, NY, p 880.