Discovery of Adiponectin and its Future Prospect

Kazuhisa Maedaaa* and Yuji Matsuzawab

Affiliation

- aDepartment of Complementary & Alternative Medicine, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka Japan.

- b Director of Sumitomo Hospital Osaka Japan.

Corresponding Author

Kazuhisa Maeda, Department of Complementary & Alternative Medicine, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka Japan, Tel: +81-668793498; E-mail: kaz@cam.med.osaka-u.ac.jp

Citation

Kazuhisa, M., et al. Discovery of Adiponectin and its Future Prospect (2014) J Diabetes Obes 1(1): 8- 13..

Copy rights

© 2014 Kazuhisa, M. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Abstract

Adiponectin is an adipocyte-specific protein abundantly present in the plasma. Since its discovery, numerous experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated that adiponectin has anti-atherogenic, antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory properties. Hypoadiponectinemia plays a key role in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome. In this manuscript, we review the discovery and establishment of adiponectin and discuss future prospects of this molecule.

Introduction

Discovery of Adiponectin

Adipose tissue plays a central role in energy balancing and an array of endocrine functions. In the Japanese Human Genome Project in 1990s, the first systematic analyses based upon a global view of gene expression of this tissue was performed[1,2].Through a systematic search of active genes over 60 cells and tissues, we established the method to identify unique genes specifically expressed in human adipose tissue.

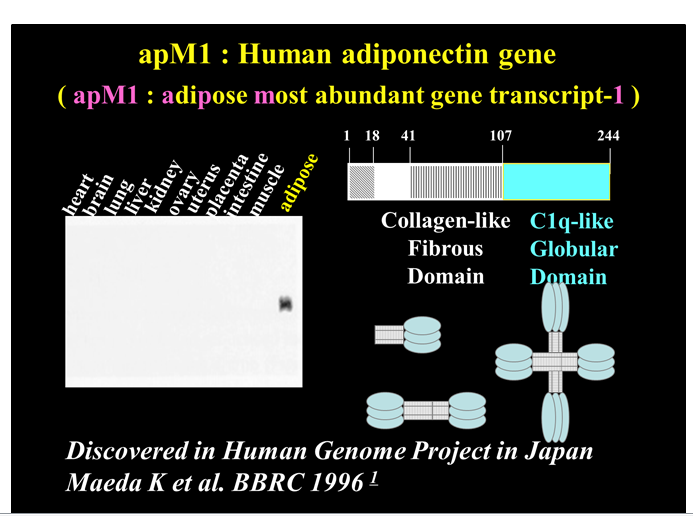

While doing a thorough systematic analysis of tissue-expressed genes we identified a new gene expressed in adipose tissues. The gene was specifically and most abundantly expressed in adipose tissue, and named as adipose most abundant gene transcript-1 (apM1)(Figure 1)[3]. Under normal conditions the adiponectin gene (apM1) is expressed exclusively in adipose tissue. ap M1 is located on chromosome 3q27, and genome-wide scans have mapped a diabetes susceptibility locus to this chromosome[4-6]. The protein is composed of a collagen-like fibrous domain and a C1q-like globular domain[7].The C terminus exhibits significant homology to collagen X and VIII and complement factor C1q. Interestingly, ACRP30 and AdipoQ were also identified at almost the same period[8,9]. Also, the same protein was identified in human plasma and called gelatin binding protein 28[10]. A wide range of multimers have been detected[7]. For example, adiponectin is present in a unique multimer form, which has been shown to be more active than low molecular weight forms[11]. Adiponectin is abundant in plasma and accounts for 0.01% of total plasma proteins in humans and 0.05% in rodents[9,12].Two adiponectin receptors have been identified. AdipoR1 is a receptor for globular adiponectin and is abundantly expressed in skeletal muscle, whereas AdipoR2,a receptor for full-length adiponectin, is mainly expressed in the liver. However, neither the physiological role of the receptors nor the signal transduction pathways have yet been fully elucidated[13].

Figure 1:

Adiponectin as a Biomarker and Mediator of Disease

Obesity might act as a mutual key player for the development of each component. The morbidity of obesity have indicated that these verity of obesity-related diseases does not necessarily correlate to the extent of body fat accumulation, but is closely related to body fat distribution. We then tried to measure its concentration in the plasma to determine its clinical significance in humans. When plasma samples were subjected to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) under non-denatured conditions, the values deviated from those expected by western blotting. Adiponectin migrated to a high molecular weight position in western blotting under non-denatured condition or in western blotting of fractionated plasma by gel filtration chromatography[12], suggesting the formation of high-ordered structure and/or binding to other plasma proteins.

The concentration of total adiponectin converted to monomeric form, ranged from 5 to 30 μg/mL. Plasma concentrations are negatively correlated with BMI, whereas leptin increases with BMI. The negative correlation of adiponectin levels and visceral adiposity is stronger than between adiponectin levels and subcutaneous adiposity[13,14], and higher concentrations were found in females compared to men. Subsequent studies revealed that serum adiponectin levels correlated negatively with visceral fat area(VFA) determined by CT[15]. In obese individuals, circulating adiponectin levels correlated negatively with VFA, but not with BMI or subcutaneous fat area (SFA)[16], suggesting that serum adiponectin concentrations are related to visceral adiposity. The mechanism by which plasma levels are reduced in individuals with VFA is not yet clarified. Co-culture with visceral fat inhibits adiponectin secretion from subcutaneous adipocytes. This finding suggests that some inhibiting factors for adiponectin synthesis or secretion are secreted from visceral adipose tissue[17].

Other studies examined the relationship between the structure and function of adiponectin. For instance, the oligomerization state is important for activation of nuclear factor (NF) κB [18], and the proteolytically cleaved globular form increases fatty acid oxidization[19]. The concentrations of adiponectin exceed those of other hormones and cytokines. Further studies on the structure of adiponectin should clarify the characteristics of this protein and delineate differences from classical endocrine proteins. A significant part of adiponectin present in plasma exists in high-molecular weight (HMW) form. Gel filtration chromatography analysis suggested that the ratio of HMW form to total adiponectin is decreased in subjects with CAD, and increased after weight reduction in obese individuals[20]. The concentrations of the HMW form of adiponectin correlated significantly with those of monomeric form-converted total adiponectin[20]. Numerous epidemiological and experimental studies have demonstrated the association between hypoadiponectinemia and several obesity-related disorders. Most of these studies are based on the assessment of total adiponectin concentration.

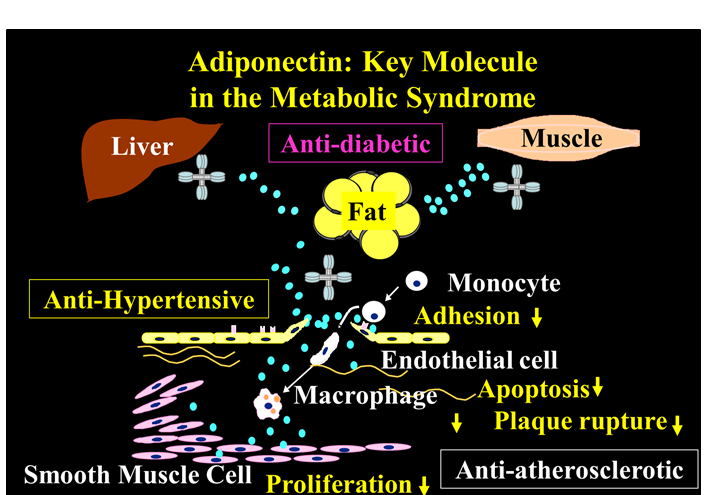

Evidence indicates that adiponectin mediates a range of anti-inflammatory, anti-atherosclerotic and antidiabetic effects, which may explain the association of low adiponectin levels with metabolic and vascular disease (Figure 2)[21-28].

Figure 2:

Adiponectin has beneficial effects on vascular function and may play a protective role against atherosclerotic vascular change as loss of its effects enhances endothelial dysfunction. A study of Japanese subjects without a history of CVD or cerebrovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, hepatic disease or renal disease indicated that increased adiponectin levels are associated with increased forearm blood flow and flow debt repayment[22]. A subsequent study in type 2 diabetes patients reported that adiponectin levels correlated with endothelial function. Plasma adiponectin correlated with endothelium-dependent vasodilation in both diabetes patients (P = 0.04) and controls (P = 0.02)[23].

The pathway by which adiponectin affects vascular function has been suggested by in vitro experiments in human aortic endothelial cells[24,25]. These cells express adiponectin receptors, and adiponectin increases nitric oxide (NO) production and/or ameliorates oxidised LDL (oxLDL)-induced suppression of eNOS (endothelial NO synthase) activity. Furthermore, endothelium-dependent vasodilation is significantly reduced in adiponectin KO mice, suggesting that loss of adiponectin is associated with impaired endothelium - dependent vasorelaxation[26].

Several studies have indicated that adiponectin possesses anti - inflammatory properties, which may alter the process of atherogenesis[21,27-33]. Studies have reported that adiponectin - deficient mice have severe neointimal thickening and increased proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells in mechanically injured arteries[34,35]. In these mice, neointimal proliferation is attenuated by adenovirus-mediated adiponectin administration[36]. This suggests that therapeutic strategies that increase plasma adiponectin levels may help to prevent vascular stenosis after angioplasty[36]. Adiponectin has also been shown to inhibit oxLDLinduced cell proliferation and suppress cellular superoxide generation[25].

One of the initial steps in atherogenesis is adherence of monocytes to endothelial cells and their migration into the sub - endothelial space, where they take up oxidised lipoproteins and transform into foam cells[37]. Adiponectin inhibits TNF - α - stimulated adherence of monocytes to cultured human endothelial cells by inhibiting expression of adhesion molecules, such as vascular cell adhesion molecule - 1 (VCAM - 1), Eselectin and intercellular adhesion molecule - 1 (ICAM - 1)[27,38].

The mechanism of adiponectin's anti - inflammatory action on the endothelium has been investigated. Nuclear transcription factor, NFκB, stimulates the expression of cytokines and adhesion molecules involved in the inflammatory process. TNF - α activates NFκB in endothelial cells by stimulating NFκB inducing kinase (NIK), which phosphorylates the NFκB inhibitor, IκB, initiating its degradation and thus leading to NFκB activation. In smooth muscle cells, adiponectin suppresses the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB. The effect of adiponectin is specific for the IκB - NFκB pathway, since no changes in the phosphorylation of other proteins induced by TNF - α have been observed[28]. This inhibitory effect of adiponectin is accompanied by cAMP accumulation and is blocked by either adenylate cyclase inhibitor or protein kinase A (PKA)[28]. In experiments with adiponectin KO mice, injection of an adiponectin producing adenovirus reversed the increased levels of adipose TNF - α messenger RNA and plasma TNF - α[21]. In line with these results, human studies found an inverse association between adiponectin and the inflammatory markers TNF - α, interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein[29-33].

Adiponectin has been shown to affect plaque formation and stability. Adiponectin suppresses lipid accumulation and class A scavenger receptor expression in macrophages, resulting in markedly decreased uptake of oxLDL and inhibition of foam cell formation[27,39,40]. It also binds to platelet - derived growth factor-BB and sub-endothelial collagens and suppresses proliferation and migration of human aortic smooth muscle cell[41,42]. It is thus well positioned to impact atherosclerosis. urthermore, adiponectin suppresses the development of atherosclerosis in vivo; it inhibited plaque lesion formation by 30% in apolipoprotein E - deficient mice compared with control mice (P < 0.05)[40].

Adiponectin may also play a role in plaque rupture through selectively increasing tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase(TIMP) expression and secretion in human monocyte-derived macrophages. This effect is mediated via the ability of adiponectin to increase the expression and secretion of IL-10 - a TIMPinducing cytokine[43].

Treatment with adiponectin improves insulin sensitivity in animal models of insulin resistance[44-46]. Intravenous adiponectin infusion has no effect on peripheral glucose uptake, glycolysis or glycogen synthesis, but lowers hepatic glucose production by reducing the expression of enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis[44]. In ddition, adiponectin reverses diet-induced insulin resistance in adiponectin KO mice[21].

These data suggest that adiponectin may exert anti-inflammatory, anti - atherogenic and anti - diabetic effects. The elucidation of mechanisms by which adiponectin influences metabolic and vascular disease provides evidence of a direct link between obesity and conditions such as type 2 diabetes and CVD. Moreover, interventions that increase plasma adiponectin levels are likely to have significant therapeutic value.

Future Scientific Perspective

Adiponectin belongs to a soluble defense collagen superfamily, and exhibits anti-inflammatory properties such as suppression of LPS-induced secretion of TNF α secretion from macrophages[47]. A recent report emonstrated that adiponectin directly binds to LPS[48]. These data suggest that adipose tissue does not only work as a self-defense system against starvation, but also against exogenous pathogens. In visceral obesity, various inflammatory cells infiltrate the adipose tissue to catch the endogenous alarming signal derived from dysfunctional adipocytes. Adiponectin forms a protein complex with complement C1q, which is another member of the soluble fense-collagen family mainly synthesized by macrophages, although its biological significance remains uncertain[49,50]. On the other hand, the expression of S100A8 is up regulated in adipocytes of obese mice[51,52]. S100A8 is considered a member of alarmin (endogenous alarm signal proteins) and forms a protein complex named calprotectin with a stabilizer, S100A9 synthesized by macrophages. Calprotectin is present in the circulation and is reported to be increased in CVD. Furthermore, the gene expression profile of peripheral leukocytes is also altered invisceral obesity[53]. Basic studies on the molecular nature of adiponectin, a new category of endocrine proteins, and studies on visceral obesity should enhance our understanding of visceral fat syndrome and help the development of strategies to prevent CVD.

Furthermore, adiponectin ratio reduced approximately 30% following gastric cancer surgery, suggested that adiponectin was an independent risk factor of postoperative infection[54]. The reduction of adiponectin levels may result from LPS-ADN binding with subsequent sequestration, which could be the useful predictor for inflammatory stress.

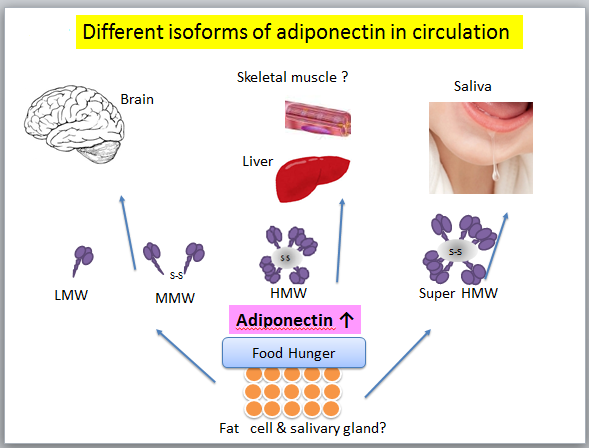

Increasing evidences have shown that several non-adipose cells or tissues also produce adiponectin and adiponectin receptors (AdipoR1/2) are expressed in various tissues and are involved in the egulation of multiple functions such as energy metabolism and inflammatory responses[55-58]. Recent study ndicates that adiponectin and its receptors are expressed among various adipose and non-adipose tissues and participate in the regulation of metabolism, structure, and function of theses tissues[8,55-58], also in human minor salivary glands[59].In rat submandibular gland, adiponectin acted as a promoter of saliva secretion[60], which was predominantly diffused in the cytoplasm of acinar cells[61]. In human, salivary.

adiponectin consisted predominantly of an extremely high molecular weight (super HWM)form[62]. Since oral duct is directly open to salivary glands cells, this super HMW form might be the original structure secretedfromthose cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Adiponectin plays a role in preventing endothelial progenitor cell senescence by inhibiting the ROS/p38 MAP kinase/p16INK4Asignaling cascade and contributes to endothelial repair in response to ascular damage[63]. It was reported that adiponectin is detectable in human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and also show that adiponectin enters the CSF from the circulation; interestingly, only trimers and hexamers but not HMW multimers could cross the blood-brain barrier[64]. In skeletal muscles, capillary endothelial of intramuscular is tight junction between epithelial cells[65]. But in liver there are small holes in the blood vessel so that HMW adiponectin could pass the vascular endothelium.

The different isoforms of adiponectin could be suitable in circulation as a biological defense protein, like Band-Aid®. When the endothelial barrier in injured by attacking factors such as oxidized LDL, adiponectin accumulates in the sub-endothelial space of vascular walls by binding to sub-endothelial collagen, at which point anti-atherogenic properties become apparent[28].

Discussion

In countries with predominant life-styles of over eating associated with ample food supply and physical inactivity associated with the use of cars and computers, obesity has become inevitable physical status. Visceral fat accumulation, rather than BMI, is closely related to glucose intolerance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. Advances in medical research have switched adipose tissue from a site for energy storage to a huge endocrine organ that produces and secretes bioactive substances and enhanced our understanding of the pathogenesis of visceral obesity. The discovery of adiponectin and subsequent extensive clinical and basic research worldwide has clarified the significance of this protein in visceral fat syndrome. More detailed clinical and experimental analyses of hypoadiponectinemia should further clarify the significance of this molecule, and may encourage physicians to recommend modification of lifestyles to their patients to reduce visceral fat and prevent CVD.

We expect this outstanding molecular may further contribute to the health of the humankinds.

Acknowledgement: Authors thank Hsiaoyun Lin for her helping assistance in prepare the manuscript.

References

- 1. Maeda, K., Okubo, K., Shimomura, I., et al. Analysis of an expression profile of genes in the human adipose tissue. (1997) Gene 190(2): 227- 235.

- 2. Okubo, K., Hori, N., Matoba, R., et al. Large scale cDNA sequencing for analysis of quantitative and qualitative aspects of gene expression. (1992) Nat Genet 2(3): 173- 179.

- 3. Maeda, K., Okubo, K., Shimomura, I., et al., cDNA cloning and expression of a novel adipose specific collagen-like factor, apM1 (adipose most abundant gene transcript 1). (1996) Biochem Biophys Res Commun 221(2): 286- 289.

- 4. Kissebah, A.H., Sonnenberg, G.E., Myklebust, J., et al. Quantitative trait loci on chromosomes 3 and 17 influence phenotypes of the metabolic syndrome. (2000) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97(26): 14478- 14483.

- 5. Takahashi, M., Arita, Y., Yamagata, K., et al., Genomic structure and mutations in adipose-specific gene, adiponectin. (2000) Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 24(7): 861- 868.

- 6. Stumvoll, M., Tschritter, O., Fritsche, A., et al. Association of the T-G polymorphism in adiponectin (Exon 2) with obesity and insulin sensitivity: Interaction with family history of type 2 diabetes. (2002) Diabetes. 51(1): 37- 41.

- 7. Waki, H., Yamauchi, T., Kamon, J., et al. Impaired multimerization of human adiponectin mutants associated with diabetes. Molecular structure and multimer formation of adiponectin. (2003) J Biol Chem. 278(41): 40352- 40363.

- 8. Scherer, P.E., Williams, S., Fogliano, M., et al. A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes. (1995) J Biol Chem 270(45): 26746- 26749.

- 9. Hu, E., Liang, P., Spiegelman, B.M. AdipoQ is a novel adipose-specific gene dysregulated in obesity. (1996) J Biol Chem 271(18): 10697- 10703.

- 10. Nakano, Y., Tobe, T., Choi-Miura, N.H., et al. Isolation and characterization of GBP28, a novel gelatin-binding protein purified from human plasma. (1996) J Biochem 120(4): 803- 812.

- 11. Pajvani, U.B., Du, X., Combs, T.P., et al., Structure-function studies of the adipocyte-secreted hormone Acrp30/adiponectin: Implications for metabolic regulation and bioactivity. (2003) J Biol Chem 278(11): 9073- 9085.

- 12. Arita, Y., Kihara, S., Ouchi, N., et al. Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. (1999) Biochem Biophys Res Commun 257(1): 79- 83.

- 13. Yamauchi, T., Kamon, J., Ito, Y., et al. Cloning of adiponectin receptors that mediate antidiabetic metabolic effects. (2003) Nature 423(6941): 762- 769.

- 14. Matsuzawa, Y., Funahashi, T., Nakamura, T. The Concept of Metabolic Syndrome: Contribution of Visceral Fat Accumulation and Its Molecular Mechanism. (2011) J Atheroscler Thromb 18(8): 629- 639.

- 15. Ryo, M., Nakamura, T., Kihara, S., et al. Adiponectin as a biomarker of the metabolic syndrome. (2004) Circ J. 68(11): 975-981.

- 16. Kishida, K., Kim, K.K., Funahashi, T., et al. Relationships between circulating adiponectin levels and fat distribution in obese subjects. (2011) J Atheroscler Thromb 18(7): 592- 595.

- 17. Halleux, C.M., Takahashi, M., Delporte, M.L., et al. Secretion of adiponectin and regulation of apM1 gene expression in human visceral adipose tissue. (2001) Biochem Biophys Res Commun 288(5): 1102-1107.

- 18. Tsao, T.S., Murrey, H.E., Hug, C., et al. Oligomerization state-dependent activation of NF-κB signaling pathway by adipocyte complement-related protein of 30 kDa (Acrp30). (2002) J Biol Chem 277(33): 29359- 29362.

- 19. Fruebis, J., Tsao, T.S., Javorschi, S., et al. Proteolytic cleavage product of 30-kDa adipocyte complement-related protein increases fatty acid oxidation in muscle and causes weight loss in mice. (2001) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98(4): 2005-2010.

- 20. Kobayashi, H., Ouchi, N., Kihara, S., et al. Selective suppression of endothelial cell apoptosis by the high molecular weight form of adiponectin. (2004) Cir Res 94(4): 27-31.

- 21. Maeda, N., Shimomura, I., Kishida, K., et al. Diet-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking adiponectin/ACRP30. (2002) Nat Med 8(7): 731-737.

- 22. Shimabukuro, M., Higa, N., Asahi, T., et al. Hypoadiponectinemia is closely linked to endothelial dysfunction in man. (2003) J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88(7): 3236- 3240.

- 23. Tan, K.C., Xu, A., Chow, W.S., et al. Hypoadiponectinemia is Associated with Impaired Endothelium-Dependent Vasodilation. (2004) J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89(2): 765- 769.

- 24. Chen, H., Montagnani, M., Funahashi, T., et al. Adiponectin Stimulates Production of Nitric Oxide in Vascular Endothelial Cells. (2003) J Biol Chem 278(45): 45021- 45026.

- 25. Motoshima, H., Wu, X., Mahadev, K., et al. Adiponectin suppresses proliferation and superoxide generation and enhances eNOS activity in endothelial cells treated with oxidized LDL. (2004) Biochem Biophys Res Commun 315(2): 264- 271.

- 26. Ouchi, N., Ohishi, M., Kihara, S., et al. Association of hypoadiponectinemia with impaired vasoreactivity. (2003) Hypertension 42(3): 231- 234.

- 27. Okamoto, Y., Kihara, S., Ouchi, N., et al. Adiponectin reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice.(2002) Circulation 106(22): 2767- 2770.

- 28. Ouchi, N., Kihara, S., Arita, Y., et al. Adiponectin, an adipocyte-derived plasma protein, inhibits endothelial NF-κB signaling through a cAMP-dependent pathway. (2000) Circulation 102(11): 1296- 1301.

- 29. Engeli, S., Feldpausch, M., Gorzelniak, K., et al., Association between adiponectin and mediators of inflammation in obese women. (2003) Diabetes 52(4): 942- 947.

- 30. Ouchi, N., Kihara. S., Funahashi, T., et al. Reciprocal association of C-reactive protein with adiponectin in blood stream and adipose tissue. (2003) Circulation 107(5): 671- 674.

- 31. Krakoff, J., Funahashi T, Stehouwer CD., et al. Inflammatory markers, adiponectin, and risk of type 2 diabetes in the Pima Indian. (2003) Diabetes Care 26(6): 1745- 1751.

- 32. Matsubara. M., Namioka. K., Katayose, S. Decreased plasma adiponectin concentrations in women with low-grade C-reactive protein elevation. (2003) Eur J Endocrinol 148(6): 657- 662.

- 33. Kern, P.A., Di Gregorio, G.B., Lu, T., et al. Adiponectin expression from human adipose tissue: Relation to obesity, insulin resistance, and tumor necrosis factor-α expression. (2003) Diabetes 52(7): 1779- 1785.

- 34. Zietz, B., Herfarth, H., Paul, G., et al. Adiponectin represents an independent cardiovascular risk factor predicting serum HDL-cholesterol levels in type 2 diabetes. (2003) FEBS Lett 545(2-3): 103-104.

- 35. Kubota, N., Terauchi, Y., Yamauchi, T., et al. Disruption of adiponectin causes insulin resistance and neointimal formation. (2002) J Biol Chem 277(29): 25863- 25866.

- 36. Matsuda, M., Shimomura, I., Sata, M., et al. Role of adiponectin in preventing vascular stenosis. The missing link of adipo-vascular axis. (2002) J Biol Chem 277(40): 37487- 37491.

- 37. Matsuzawa, Y., Funahashi, T., Kihara, S., et al., Adiponectin and Metabolic Syndrome. (2004) Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24(1): 29- 33.

- 38. Ouchi, N., Kihara, S., Arita, Y., et al. Novel modulator for endothelial adhesion molecules: Adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin. (1999) Circulation 100(25): 2473- 2476.

- 39. Ouchi, N., Kihara, S., Arita, Y., et al. Adipocyte-derived plasma protein, adiponectin, suppresses lipid accumulation and class A scavenger receptor expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages. (2001) Circulation 103(8): 1057- 1063.

- 40. Yamauchi, T., Kamon, J., Waki, H., et al. Globular adiponectin protected ob/ob mice from diabetes and ApoE-deficient mice from atherosclerosis. (2003) J Biol Chem 278(4): 2461- 2468.

- 41. Arita, Y., Kihara, S., Ouchi, N., et al. Adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin acts as a platelet-derived growth factor-BB-binding protein and regulates growth factor-induced common postreceptor signal in vascular smooth muscle cell. (2002) Circulation 105(24): 2893- 2898.

- 42. Okamoto, Y., Arita, Y., Nishida, M., et al. An adipocyte-derived plasma protein, adiponectin, adheres to injured vascular walls. (2000) Horm Metab Res 32(2): 47- 50.

- 43. Kumada, M., Kihara, S., Ouchi, N., et al. Adiponectin Specifically Increased Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-1 Through Interleukin-10 Expression in Human Macrophages. (2004) Circulation 109(17): 2046- 2049.

- 44. Combs, T.P., Berg, A.H., Obici, S., et al. Endogenous glucose production are inhibited by the adipose-derived protein Acrp30. (2001) J Clin Invest 108(12): 1875- 1881.

- 45. Yamauchi, T., Kamon, J., Minokoshi, Y., et al. Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. (2002) Nature Medicine 8(11): 1288- 1295.

- 46. Stefan, N., Stumvoll, M., Vozarova, B., et al. Plasma Adiponectin and Endogenous Glucose Production in Humans. (2003) Diabetes Care 26(12): 3315- 3319.

- 47. Yokota, T., Oritani, K., Takahashi, I., et al. Adiponectin, a new member of the family of soluble defense collagens, negatively regulates the growth of myelomonocytic progenitors and the functions of macrophages. (2000) Blood 96(5): 1723- 1732.

- 48. Peake, P.W., Shen, Y., Campbell, L.V., et al. Human adiponectin binds to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. (2006) Biochem Biophys Res Commun 41(1): 108- 115.

- 49. Nakatsuji, H., Kobayashi, H., Kishida, K., et al. Binding of adiponectin and C1q in human serum, and clinical significance of the measurement of C1q-adiponectin / total adiponectin ratio. (2013) Metabolism 62(1): 109- 120.

- 50. Hirata, A., Kishida, K., Kobayashi, H., et al. Correlation between serum C1q-adiponectin/total adiponectin ratio and polyvascular lesions detected by vascular ultrasonography in Japanese type 2 diabetics (2013) Metabolism Clinical and Experimental 62(3): 376– 385.

- 51. Hiuge-Shimizu, A., Maeda, N., Hirata, A., et al. Dynamic changes of adiponectin and S100A8 levels by the selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonist rivoglitazone. (2011) Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31(4): 792- 799.

- 52. Sekimoto, R., Kishida, K., Nakatsuji, H., et al. High circulating levels of S100A8/A9 complex (calprotectin) in male Japanese with abdominal adiposity and dysregulated expression of S100A8 and S100A9 in adipose tissues of obese mice (2012) Biochem Biophys Res Commun 419(4): 782- 789.

- 53. Yamaoka, M., Maeda, N., Nakamura, S., et al. A Pilot Investigation of Visceral Fat Adiposity and Gene Expression Profile in Peripheral blood Cells. (2012) PLoS One 7(10): e47377.

- 54. Yamamoto, H., Maeda, K., Uji, Y., et al. Association between reduction of plasma adiponectin levels and risk of bacterial infection after gastric cancer surgery. (2013) PLoS One 8(3): e56129.

- 55. Pineiro, R., Iglesias, M.J., Gallego, R., et al. Adiponectin is synthesized and secreted by human and murine cardiomyocytes. (2005) FEBS Lett 579(23): 5163- 5169.

- 56. Krause, M.P., Liu, Y., Vu, V., et al. Adiponectin is expressed by skeletal muscle fibers and influences muscle phenotype and function. (2008) Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295(1): C203- C212.

- 57. Maresh, J.G., Shohet, R.V. In vivo endothelial gene regulation in diabetes. (2008) Cardiovasc Diabetol 7: 8.

- 58. Ding, M., Carrão, A.C., Wagner, R.J., et al. Vascular smooth muscle cell-derived adiponectin: a paracrine regulator of contractile phenotype. (2012) J Mol Cell Cardiol 52(2): 474- 484.

- 59. Katsiougiannis, S., Kapsogeorgou, E.K., Manoussakis, M.N., et al. Salivary gland epithelial cells: a new source of the immunoregulatory hormone adiponectin. (2006) Arthritis Rheum 54(7): 2295- 2299.

- 60. Ding, C., Li, L., Su, Y.C., et al. Adiponectin increases secretion of rat submandibular gland via adiponectin receptors-mediated AMPK signaling. (2013) PLoS One 8(5): e63878.

- 61. Su, Y.C., Xiang, R.L., Zhang, Y., et al. Decreased submandibular adiponectin is involved in the progression of autoimmune sialoadenitis in NOD mice. (2013) Oral Dis.

- 62. Lin, H., Maeda, K., Fukuhara, A., et al. Molecular expression of adiponectin in human saliva. (2014) Biochem Biophys Res Commun 445(2): 294- 298.

- 63. Chang, J., Li, Y., Huang, Y., et al. Adiponectin Prevents Diabetic Premature Senescence of Endothelial Progenitor Cells and Promotes Endothelial Repair by Suppressing the p38 MAP Kinase/p16INK4A Signaling Pathway. (2010) Diabetes 59(11): 2949- 2959.

- 64. Kubota, N., Yano, W., Kubota, T., et al. Adiponectin stimulates AMP-activated protein kinase in the hypothalamus and increases food intake. (2007) Cell Metab 6(1): 55- 68.

- 65. Iso, T., Maeda, K., Hanaoka, H., et al. Capillary endothelial fatty acid binding proteins 4 and 5 play a critical role in fatty acid uptake in heart and skeletal muscle. (2013) Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33(11): 2549- 2557.