Effect of Bedtime Pistachio Consumption for 6 weeks on Body Weight, Glycemic and Lipid Profile in Obese Persons

Ted Wilson1*, Jessica R. Young1, Ashley D. Anderson1, Melanie M. Anderson1, Janel L. Jacobson1, Mackenzie R. Popko1, Yifei Wang2, Ajay P Singh2, Nicholi Vorsa2, Paul J. Limburg3, Tisha Hooks4 and Arianna Carughi4

Affiliation

- 1Department of Biology, Winona State University, Winona, MN

- 2Philip E. Marucci Center for Blueberry and Cranberry Research and Extension, Plant Biology and Pathology, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ

- 3Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN

- 4Tisha Hooks, Mathematics & Statistics, Winona State University, Winona, MN

- 5GNLD International, Fremont, CA

Corresponding Author

Ted Wilson, Department of Biology, Winona State University, Winona, MN 55987, E-mail: ewilson@winona.edu

Citation

Wilson,T. et, al. Effect of Bedtime Pistachio Consumption for 6 weeks on Weight, Lipid Profile and Glycemic Status in Overweight Persons (2014) J Food Nutr Sci 1(1): 13-16.

Copy rights

©2014 Wilson,T. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Abstract

Overweight persons trend for dyslipidemia and diabetes risk, while mono- and polyunsaturated fats in pistachios (PI) may improve lipoprotein and glycemic status. This study determined if a small amount of PI consumed by obese persons at bedtime promotes beneficial changes in metabolic status. Obese subjects were randomized to 35.4 g PI self-administered at bedtime or control (CO; no PI) for 6 weeks. There was no difference in activity level,body weight, or BMI between PI and CO at weeks 0, 1, 2, 4 or 6. Plasma glucose at wk 0 and 6 in PI was 104.6 ± 13.1 and 99.6 ± 12.2 mg/dL, and CO was 102.0 ± 12.8 and 101.1 ± 12.2 mg/dL; from wk 0 to wk 6 PI had improved slightly (P= 0.09). In conclusion 35.4 grams pistachios/day for 6 wks is probably near the lower end of what is needed to promote beneficial metabolic changes. This study suggests that 35g of pistachios per day at bedtime may be the minimum daily amount to observe beneficial effects in an obese population. Future studies may wish to examine pistachio consumption in populations with specific metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes.

Introduction

Obesity is a risk factor associated with type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease and may be influenced by diet. Evening snacking can be a risk factor associated with development of obesity[1]. The Dawn phenomenon is a diabetic complication resulting in late night disordered glucose homeostasis[2,3]. Cholesterol synthesis is known to peak late in the evening[4]. Diets rich in mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids can lower LDL and total cholesterol, as well as increase HDL cholesterol, which is linked to development of or protection from cardiovascular disease [5-7]. In contrast dietary saturated fats tend to increase LDL cholesterol and the risk of type 2 diabetes [8]. Therefore nutritional qualities in a snack delivered at bedtime could alter carbohydrate and lipid metabolism and the metabolic events that occur in the evening as part of the circadian rhythm.

Pistachios have a high nutrient density, and potential to give a sense of satiety leading to lower caloric consumption in a subsequent meal[9]. Pistachios are high in monounsaturated fats, polyunsaturated fats, and fiber which potentially lead to improved cholesterol profiles. Pistachios are also known to be rich in phytosterols, such as B-sitosterol[10], that have the capacity to lower LDL-cholesterol by reducing cholesterol absorption from the gut[11]. Compared to other nuts, pistachios have lower fat (mostly from poly- and monounsaturated fatty acids) and energy content, and higher levels of fiber (both soluble and insoluble), potassium, phytosterols, γ-tocopherol, xanthophyll and carotenoids. Because pistachios are low in total carbohydrates and sugars(27.5 g /100 g and 7.6 g /100 g respectively) they have a very low glycemic index that is in the range of 3.8 to 9.3[12] giving pistachios utility for improved postprandial blood glucose and lipids.

Prior pistachio studies of the beneficial metabolic effects are legion with caloric intake representing 15% of caloric intake[13], 16% and 27% of caloric intake[14], 20% of caloric intake[15,16], while the USDA suggested single serving size for pistachios is 1 ounce (30 grams) of kernels (49 grams with shell) or 1 ounce protein equivalent[17]. Choice of a serving size that reflects an amount commonly consumed is also an important consideration when evaluating the metabolic effect of a snack, and a 200 Calorie serving is currently recommended for snack size[18]. The time of administration can also influence the metabolic consequence of the snack. Effects of a snack at bedtime with a low glycemic index, high protein content and favorable ratio of mono- and polyunsaturated fats has not been investigated in this regard. The present study sought to determine the effect of consumption of a small 35 g (1.25 oz)serving of pre-peeled pistachios (8.3% of daily caloric intake) self-administered at bedtimeon weight maintenance, lipid profile, and glycemic status.

Materials and Methods

Study population

This study was approved by the Winona State University Institutional Review Board with subjects recruited through email, posters, and newspapers. A total of 22 obese subjects were enrolled in this 42 day study (16 female and 6 male; 54.7± 8.7 years of age; BMI = 31.1 ± 4.0). Study subject exclusions included smoking, use of medications for improving blood cholesterol, insulin-dependent diabetes or medication for diabetes, medications for inflammation/arthritis (i.e. corticosteroids), recent treatment for cancer or heart disease within the last 6 months, liver disease, or use of anticoagulants (such as Plavix or Coumadin). All of the subjects completed a seven day wash-out period during which they discontinued consumption of alcohol, fish oil, and all nut products prior to their first laboratory visit.

Pistachio consumption, and plasma analysis

Subjects were randomized upon laboratory presentation on the first study morning to receive either no intervention (control) or an intervention consisting of 35 g pre-shelled, roasted, unsalted pistachios self-administered at bedtime for 42 days. This serving contained 200 total Calories representing 8.3 % of their weight/age activity adjusted daily caloric intake containing 15.88 g total fat (1.93 g saturated, 8.39 g monounsaturated, and 4.76 g polyunsaturated fat), 7.73 g protein, 2.74 g sugars, and 3.50 g fiber[17]. Subjects abstained from all food or drink (except water) and did not exercise during the twelve-hour fast period prior to laboratory arrival (6-8AM) subjects and randomization to treatments prior to blood collection. Venous blood samples were collected at study onset (day-0) and at study completion (day-42).

Collected plasma samples were frozen at -80oC until analysis in single blind fashion on a single day using freshly thawed samples. Plasma glucose was measured with a Hitachi 912 Chemistry Analyzer using hexokinase reagent from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, Indiana, USA). Insulin was measured with a two-site immunoenzymatic assay performed on the DxI automated immunoassay system (Beckman Instruments, Chaska, Minnesota, USA). Plasma triglycerides, total cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol were also measured, and LDL cholesterol was estimated using the Friedewald equation.

Subjects were required to complete daily dietary journals and exercise records (in minutes) to evaluate compliance with dietary restrictions and to estimate activity level throughout the study. Weight was measured on days 0, 7, 14, 28, and 42 when subjects returned to the lab for food diary review and to receive more pistachios.

Pistachio Phytochemical Analysis

Pistachios (2 g) were crushed in liquid nitrogen,transferred into 10 ml solvent (95% n-hexane, 80% acetone + 0.1% acetic acid or 50% methanol) followed by 5 min vortex homogenization and 10 min sonication. After centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 20 min the supernatants and pellets were collected separately. Extracts were dried in a rotary evaporator at 40ºC and redissolved in 100% methanol for analysis. A Dionex® UltiMate 3000 UPLC system coupled with Applied Biosystems API 3000 TM LC/MS/MS system was used for qualitative and quantitative analysis. The Gemini® 150 x 4.6 mm 5 μm C18 110 Å LC column was used for liquid chromatographic separation with solvent A: 0.1% formic acid in water and solvent B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile under the following gradient conditions:0% B to 15% B from 0-1 min; 15% B to 16% B from 1-5 min; 16% B from 5-10 min; 16% B to 17% B from 10-25 min 17% B from 25-28 min;17% B to 30% B from 28-30 min; 30% B to 45% B from 30-38 min; 45% B to 80% B from 38-40 min; 80% B to 0% B from 40-43 min; 0% B from 43-50 min with a flow rate of 1 ml/min. MS analysis was carried out in heated nebulizer ion source in negative ion mode with source temperature (500°C), curtain gas (12 psi), nebulizer gas (7 psi), collision gas (6 psi), entrance potential (-9 V), collision energy (-20 V), collision cell exit potential (-3 V) and declustering potential (-60 V). Compound structure was determined by comparison with those of standards. Compound quantification was carried out in multiple reaction monitoring scan mode based on calibration curves generated from standards. Data was acquired in Analyst software, version 1.4.2.

Statistical Analysis

All summaries for human numerical response variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Body weight, BMI, and data from the venous blood samples were analyzed using a repeated measures ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test where appropriate.

Results and Discussion

Pistachio serving as percent of total caloric intake

All 22 subjects who arrived at the laboratory on day-0 completed the 42 day study. Daily food diaries were examined weekly to evaluate compliance with study requirements, and discrepancies (i.e. failure to record diet, failure to eat pistachio snack or accidental consumption of peanuts) were observed on 32 of the 924 total participation days. Daily activity levels were not significantly different between groups across time. Activity, age and BMI adjusted caloric requirements were calculated[19] for each participant. Criteria for sedentary, low active, and active activity levels were met by 6, 14, and 2 participants respectively, yielding an average of 35 ± 13 minutes walking/day. This was associated with an overall estimated daily requirement of 2424 ± 498 Cal/day; therefore the 35g pistachio snack represented 8.3% of total caloric needs. The amount of pistachios administered in this study was about half or less than those used in the previous studies of Sheridan et. al. 2007 (15%)[13], Wang et. al. 2012 (16% and 20%) [14], Edwards et. al. 1999 (20%) [15], and Li et. al. 2010 (20%)[16].

Pistachio effects on body weight and BMI

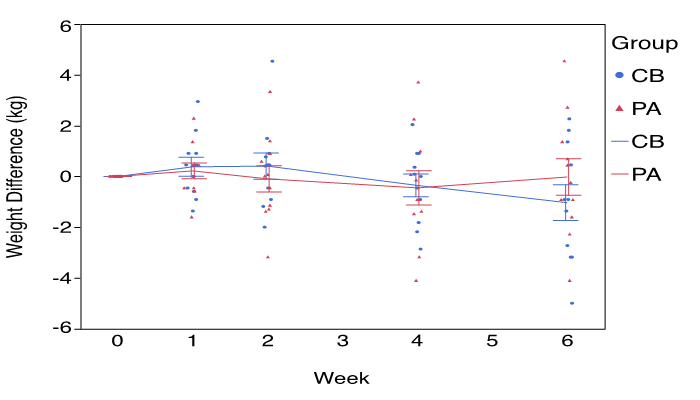

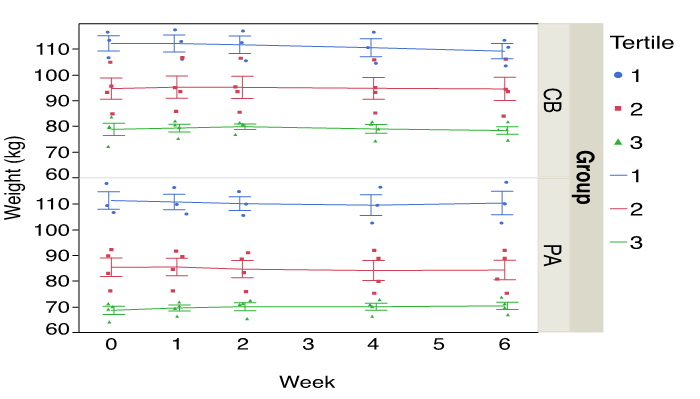

Weight maintenance is a primary concern among overweight persons which may prevent them from receiving health benefits associated with nuts such as pistachios[9]. Pistachio consumption in the present study was associated with neutral weight effects for the overweight persons in this study. Body weight differences at weeks 2-6 relative to week-0 were not affected by pistachio consumption (Figure 1). The 200 Calorie serving represented smaller and larger percentages of total caloric intake in the upper and lower tertiles based on BMI at study initiation, respectively. Therefore a tertile analysis was evaluated,and no statistically significant differences in weight were observed between treatments or within or between tertiles. (Figure 2). BMI of subjects in the control group had day-0 and day-42 BMI values of 32.1 ± 4.4 and31.8 ± 4.5, respectively and BMI in the pistachios group had day-0 and day-42 values of 30.2 ± 3.6 and 30.2 ± 3.3, respectively, with no statistically significant effect observed between or within groups. Several prior human studies have failed to confirm that pistachio consumption leads to changes in body weight[13,14,20-22]. The present study demonstrates that consumer concerns about weight gain associated with the pistachio lipidand caloric content for the 35 g serving are unwarranted.

Pistachio effects on plasma glucose, insulin and lipid profile

Reductions in fasting plasma glucose and insulin are important clinical targets for persons with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome who often express obesity as a comorbidity. In the present study bedtime consumption of 35 g pistachios for 42 days was associated with a trend toward beneficial reductions in fasting plasma glucose (P = 0.09; Table 1). Pistachio consumption had no statistically significant effects on plasma insulin or plasma lipid profile (Table 1). Other investigators have examined the effect of pistachio consumption on glycemic and insulinemic profile. A beneficial improvement in fasting glucose has been observed when pistachios (20% of daily caloric need) were administered for 4 weeks[21]; in contrast, pistachio-dependent changes in insulin and glucose have not always been observed[13,14], perhaps because of their larger amounts of pistachios consumed or their daytime consumption. Degree of mastication can also influence the glycemic and insulinemic response to almond [23]. In the present study subjects were asked to chew thoroughly but were not given a specific number of chews prior to swallowing because the investigators had no way to quantify pistachio masticative efficiency given the bedtime administration restriction. The present study excluded those with diabetes whose fasting glucose and insulin values might be more likely to benefit. Future therapeutic evaluations of pistachio consumption may be warranted for persons with type 2 diabetes or fasting hyperglycemia.

Figure 1: Pistachio consumption (1.25 oz) at bedtime had no statistically significant effect on body weight within or between groups (mean ± stdev). Please key to CB,PA.

Figure 2: Pistachio consumption was not associated with significant differences in weight between treatments or between or within tertiles (mean ± stddev).

It is worth noting that none of these prior studies administered the phytosterol-rich pistachios at bedtime, when the nuts might have the greatest potential impact on the metabolic pathways that lead to obesity, dyslipidemia, and type 2 diabetes. Pistachios consumed alone have been shown to have a minimal effect on postprandial glycemia, the addition of pistachios (28g, 56g or 84g) to foods with a high glycemic index (pasta, parboiled rice and mashed potatoes) reduce, in an acute dose-dependent manner, the total postprandial glycemic response by 20 to 30%[12]. The beneficial impact of pistachio intake alone or in combination with high-carbohydrate foods on post-prandial glycemia has also been demonstrated[12]. Bedtime administration of pistachios in the present study permitted the investigators to exclude effects of satiety potential caloric intake or insulin sensitivity following snack administration.

Table: Effect of pistachio consumption for 42 days (1.25 oz at bedtime) on plasma glucose, insulin, high density lipoprotein, low density lipoprotein, total cholesterol, and triglycerides (mean ± stdev)

| Week | Control | Pistachio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 0 | 102.0 ± 2.8 | 104.6 ± 2.8 |

| 6 | 101.1 ± 2.6 | 99.6 ± 2.6(P = 0.16) | |

| Insulin (μU/mL) | 0 | 7.2 ± 0.7 | 8.5 ± 1.0 |

| 6 | 8.8 ± 0.7 | 8.4 ± 0.9(P = 0.21) | |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0 | 60.8 ± 3.8 | 49.2 ± 3.5 |

| 6 | 58.0 ± 2.7 | 50.3 ± 3.0(P = 0.12) | |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0 | 150.7 ± 28.8 | 161.9 ± 30.2 |

| 6 | 144.6 ± 30.4 | 152.4 ± 27.9 | |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0 | 211.6 ± 29.9 | 211.1 ± 30.7 |

| 6 | 202.6 ± 31.3 | 202.6 ± 24.7 | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 0 | 120.6 ± 51.7 | 123.7 ± 41.8 |

| 6 | 111.3 ± 49.0 | 118.2 ± 33.7 | |

| P-value of trend towards significance within group is indicated in bold italics. | |||

Plant phenolicshave been suggested to have beneficial health effects related to diabetes, cardiovascular disease, inflammation, antioxidant protection and the gut microbiome. Glycosides of quercetin and catechin have been implicated in altered intestinal α-glucosidase and pancreatic α-amylase activities and glucose absorption from the gut [24,25], and potential to alter glycemic responses to pistachios. Pistachios are known to be high in anthocyanins, chlorophylls, carotenoids and phytosterols[26,27]. The γ-tocopherol content was 115 μg/gin n-hexane extract, similar to that observed[26]. Analysis of the phenolic profile of the pistachios used in this study yielded additional characterizations. The pistachio free catechin content was 0.041 mg/g in the 80% aqueous acetone extract. In the 50% ethanol extract myrecetin-3-galactoside, quercetin-3-galactoside, quercetin-3-rhamnoside and free quercetin were present at 0.76 μg/g, 2.08 μg/g, 2.05 μg/g, and trace levels respectively. This represents the first quantification of flavanolicglycosides in pistachios, although anthocyanins such as cyanidin-3-glycoside have been previously observed in pistachioskin in the 68-876 μg/g range[26] and 109-429 μg/g range[27].

Conclusion

This is the first study of once daily pistachio consumption at bedtime in obese persons. Consumption of 35 g pistachios at bedtime by overweight persons for 42 days was not associated with statistically significant changes in plasma insulin, plasma lipids, body weight, BMI, or activity level. Trends toward a beneficial effect were observed for glucose. This study was also the first to observe flavonolic glycosides in pistachios. This study suggests that 35 g per day at bedtime is near the minimum daily amount needed for beneficial metabolic effects and not associated with increases in body weight.

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by a WSU PIF grant, a WSU Foundation grant, and an unrestricted grant from the American Pistachio Growers Association.

References

- 1. Colles, S.L., Dixon, J.B., O'Brien, P.E. Night eating syndrome and nocturnal snacking: association with obesity, binge eating and psychological distress. (2007) Int J Obes (Lond) 31(11): 1722–1730.

- 2. Bolli, G.B., Gerich, J.E. The 'dawn phenomenon'-a common occurrence in both non-insulin-dependent and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. (1984) N Engl J Med 310(12): 746-750.

- 3. Monnier, L., Colette, C., Sardinoux, M., et al. Frequency and severity of the dawn phenomenon in type 2 diabetes: relationship to age. (2012) Diabetes Care 35(12): 2597-2599.

- 4. Gälman, C., Angelin, B., Rudling, M. Bile acid synthesis in humans has a rapid diurnal variation that is asynchronous with cholesterol synthesis. (2005) Gastroenterology 129(5): 1445-1453.

- 5. Anderson, J.W., Konz, E.C. Obesity and disease management: effects of weight loss on comorbid conditions. (2012) Obes Res 9(11): 326S-334S.

- 6. Rossi, A.P., Fantin, F., Zamboni, G.A., et al. Effect of moderate weight loss on hepatic, pancreatic and visceral lipids in obese subjects. (2012) Nutr Diabetes 2: e32.

- 7. Leichtle, A.B., Helmschrodt, C., Ceglarek, U., et al. Effects of a 2-y dietary weight-loss intervention on cholesterol metabolism in moderately obese men. (2011) Am J Clin Nutr 94(5): 1189-1195.

- 8. Fats and fatty acids in human nutrition. Report of an expert consultation. (2008) FAO Food Nutr Pap. Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations.

- 9. Mattes, R.D., Dreher, M.L. Nuts and healthy body weight maintenance mechanisms. (2010) Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 19(1): 137-141.

- 10. Phillips, K.M., Ruggio, D.M., Ashraf-Khorassani, M. Phytosterol composition of nuts and seeds commonly consumed in the United States. (2005) J Agric Food Chem 53(24): 9436-9445.

- 11. Laitinen, K., Gylling H. Dose-dependent LDL-cholesterol lowering effect by plant stanol ester consumption: clinical evidence. (2012) Lipids Health Dis 11:140.

- 12. Kendall, C.W., Josse, A.R., Esfahani, A., et al. The impact of pistachio intake alone or in combination with high-carbohydrate foods on post-prandial glycemia. (2011) Eur J Clin Nutr 65(6): 696-702.

- 13. Sheridan, M.J., Cooper, J.N., Erario, M., et al. Pistachio nut consumption and serum lipid levels. (2007) J Am Coll Nutr 26 (2): 141-148.

- 14. Wang, X., Zhaoping L., Yanjun L., et al. Effects of pistachios on body weight in chinese subjects with metabolic syndrome. (2012) Nutr J 11: (20).

- 15. Edwards, K., Kwaw, I., Matud, J., et al. Effect of pistachio nuts on serum lipid levels in patients with moderate hypercholesterolemia. (1999) J Am Coll Nutr 18(3): 229-232.

- 16. Li, Z., Song, R., Nguyen, C., et al. Pistachio nuts reduce triglycerides and body weight by comparison to refined carbohydrate snack in obese subjects on a 12-week weight loss program. (2010) J Am Coll Nutr 29(3):198-203.

- 17. Nutrient data for 12152, Nuts, pistachio nuts, dry roasted, without salt added. USDA.gov. National Agricultural Library. Accessed 24 March 2013.

- 18. Virginia,A.S., Ann, L.Y. editors. Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools: Leading the Way Toward Healthier Youth. (2007) Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- 19. Kocyigit, A., Koylu, A.A., Keles, H. Effects of pistachio nuts consumption on plasma lipid profile and oxidative status in healthy volunteers. (2006) Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 16(3): 202-209.

- 20. Sari, I., Baltaci, Y., Bagci C., et al. Effect of pistachio diet on lipid parameters, endothelial function, inflammation, and oxidative status: a prospective study. (2010) Nutrition 26(4): 399-404.

- 21. Gulati, S., Misra, A., Pandey, R.M., et al. Effects of pistachio nuts on body composition, metabolic, inflammatory and oxidative stress parameters in Asian Indians with metabolic syndrome: a 24-wk, randomized control trial. (2014) Nutrition 30(2): 192-197.

- 22. Cassady, B.A., Hollis, J.H., Fulford, A.D., et al. Mastication of almonds: effects of lipid bioaccessibility, appetite, and hormone response. (2009) Am J Clin Nutr 89(3): 794-800.

- 23. Wilson, T., Luebke, J.L., Morcomb, E.F., et al. Glycemic responses to sweetened dried and raw cranberries in humans with type 2 diabetes. (2010) J Food Sci 75(8): H218-223.

- 24. Akkarachiyasit, S., Charoenlertkul, P., Yibchok-Anun, S., et al. Inhibitory activities of cyanidin and its glycosides and synergistic effect with acarbose against intestinal α-glucosidase and pancreatic α-amylase. (2010) Int J Mol Sci 11(9): 3387-3396.

- 25. Liu, Y., Blumberg, J.B., Chen, C.Y. Quantification and bioaccessibility of california pistachio bioactives. (2014) J Agric Food Chem 62(7): 1550-1556.

- 26. Bellomo, M.G.,Fallico, B. Anthocyanins, chlorophylls and xanthophylls in pistachio nuts (Pistaciavera) of different geographic origin. (2007) Food Comp Anal 20(3-4): 352-359.