Epigallocatechin Gallate Differentially Modulates Interleukin Secretion in Nicotine and TNFα-Treated Human Gingival Epithelial Cells

Affiliation

Department of Biomedical and Diagnostic Sciences, University of Detroit Mercy School of Dentistry, Detroit, Michigan, USA

Corresponding Author

Michelle A. Wheater, Department of Biomedical and Diagnostic Sciences, University of Detroit Mercy School of Dentistry, Detroit, Michigan, USA. Tel: (313) 494-6634; Fax: (313) 494-6643; E-mail: wheatemi@udmercy.edu

Citation

Wheater, M., et al. Epigallocatechin Gallate Differentially Modulates Interleukin Secretion in Nicotine and TNFα-Treated Human Gingival Epithelial Cells. (2015) J Dent & Oral Care 1(2): 1- 5.

Copy rights

©2015 Wheater, M. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Keywords

Cytokines; Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG); Nicotine; Tumor necrosis factor alpha

Abstract

Objectives: To determine the effects of Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG), a major catechin component of green tea, on cytokine expression in a human oral epithelial cell culture model of nicotine use.

Methods: Confluent gingival epithelial cells in wells of a 24-well plate were subjected to one of six treatments. For controls cells received 1) No treatment or 2) Were treated with 10 μg /ml EGCG for 1 hour and cultured for 24 hours prior to analysis. A set of cells were pre-treated for 1 hour with 10 μg /ml EGCG and 3) Treated for 24 hours with 0.1 mM nicotine prior to challenge with 10 ng/ml TNFα for 1 hour, or 4) Not treated with nicotine but challenged with TNFα for 1 hour prior to analysis. A setof cells were not pre-treated with EGCG and 5) Treated for 24 hours with 0.1 mM nicotine prior to challenge with 10 ng/ml TNFα for 1 hour, or 6) Not treated with nicotine but challenged with TNFα for 1 hour prior to analysis. Culture medium samples were assayed for levels of secreted interleukins IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 by ELISA. Statistical analysis was completed for individual interleukins using ANOVA and Tukey post-test with probability set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results: The levels of IL-4 for all treatments were below the detection limit of the ELISA. EGCG significantly suppressed the secretion of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 in nicotine and TNFα-treated cells (p < 0.01). In contrast, the presence of EGCG resulted in a significant increase in the secretion of IL-10 in nicotine and TNFα-treated cells (p < 0.001).

Conclusion: This study suggests that tea catechins such as EGCG may function to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines and to increase the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in cells challenged by nicotine and TNFα.

Introduction

Periodontitis literally means "inflammation of the tooth." As an inflammatory disease, cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in the progression of periodontitis involve the production of cytokines and other proinflammatory mediators, leading to oral tissue destruction. Proinflammatory cytokines include the family of interleukins (IL) such as IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8.

According to NHANES III data, after adjusting for age, race or ethnicity, income, and educational level, smokers are four times more likely to have periodontitis as compared to non-smokers[1]. Cigarette smoke contains more than 4700 chemicals, with nicotine comprising the major compound. Based on multiple studies utilizing whole cigarette smoke, smoke extracts, or isolated chemicals, nicotine has been implicated as a major promoter of gingivitis and periodontitis in smokers.

When specifically considering effects on the oral cavity nicotine has been shown to inhibit the in vitro attachment and growth of human periodontal ligament fibroblasts[2]. Nicotine upregulated the secretion of the pro-inflammatory interleukins IL-6 and IL-8 in gingival epithelial cells and fibroblasts[3], and IL-8 was upregulated in human gingival epithelial cells in culture exposed to cigarette smoke extract[4]. In a study of human experimental gingivitis a significantly higher amount of IL-8 was detected in crevicular fluid in smokers compared to non-smokers[5], and nicotine stimulated the production of IL-1α in human gingival keratinocytes[6]. In gingival fibroblasts derived from healthy volunteers, nicotine had the greatest effect on the expression of GRO-α, IL-7, IL-10, and IL-15 compared to untreated controls[7]. Patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis exhibited higher serum levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα compared to those with generalized chronic periodontitis or periodontal health; in these same populations there were low to undetectable levels of IL-4[8].

Green tea is the second most frequently consumed beverage in the world after water and is gaining favor as a natural compound that promotes oral health[9]. The beneficial antioxidant properties of tea are due in the main to the abundance of polyphenols in the tea plant. There are four main polyphenols in tea, known as catechins. Epigallocatechin 3 gallate (EGCG) constitutes about 59% of total catechins, epigallocatechin (EGC) about 19%, epicatechin 3 gallate (ECG) about 13.6%, and epicatechin (EC) about 6.4%. Catechins have been shown to be effective antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory compounds both in vivo and in vitro; with the purported anti-inflammatory properties of particular interest with regards to periodontal disease[10,11]. Some studies have shown a relationship between catechins and inhibition of pro-inflammatory interleukins. For example EGCG and ECG suppressed IL-17A-induced CCL20 production in human gingival fibroblasts[12]. There is experimental support that EGCG inhibits multiple inflammatory cytokines including IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12 and TNFα[13-16].

In non-oral tissues, there are numerous analyses of the benefits of EGCG in inflammatory diseases. As just a few examples, EGCG decreased IL-6 and IL-8 secretion in inflamed intestinal tissue[17] and significantly reduced the inflammatory response in liver cells[18]. In a murine model EGCG attenuated the production of TNFα and MIP-2, and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and JNK following intra tracheal injections of lipopolysaccharide[19].

In tobacco users, a combination of nicotine insult on oral tissues and cells with the concurrent inflammatory reactions result in localized increased cytokine production. This in turn may contribute to increased breakdown of periodontal tissues. Clearly mechanisms that dampen inflammatory responses to nicotine would be beneficial to the smoker. Indeed Hosokawa et al[20], have proposed that green tea and black tea polyphenols could be used to provide direct benefits in periodontal disease. This is based on the observation that EGCG inhibits tumor necrosis factor superfamily 14-induced IL-6 production in human gingival fibroblasts.

The objective of this current study was to determine if EGCG can influence cytokine expression in a human oral epithelial cell culture model of nicotine use. We hypothesize that in an in vitro model of human oral mucosa nicotine exposure, EGCG will promote increased secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines, and decreased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This report used an in vitro study design of human cell culture.

Reagents and Preparation

Nicotine as nicotine hydrogen tartrate salt, EGCG solid isolated from green tea, and human recombinant TNFα were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Based on previous work, and on dose-response experiments completed using the gingival epithelial cells in this study (data not shown), the following concentrations were used: 0.1 mM nicotine, 10 μg/ml EGCG, and 10 ng/ml TNFα. The solutions were prepared in culture medium and sterilized by passage through 0.22 μm syringe filters.

Human Gingival Epithelial Cell Culture

Non-transformed human gingival epithelial cells from pooled donors were obtained from a commercial source (Science Cell, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells were cultured in T-75 flasks in serum-free oral keratinocyte medium as formulated by the manufacturer, at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2, until approximately 80% confluence. Cells were then trypsinized and plated into the appropriate culture ware for experiments. Epithelial cells were used between passages two and three.

ELISA Analysis of Interleukin Secretion

Confluent gingival epithelial cells in wells of a 24-well plate were subjected to one of six treatments. As controls cells received 1) no treatment or 2) were treated with 10 μg/ml EGCG for 1 hour and cultured for 24 hours prior to analysis. A set of cells were pre-treated for 1 hour with 10 μg/ml EGCG and 3) treated for 24 hours with 0.1 mM nicotine prior to challenge with 10 ng/ml TNFα for 1 hour, or 4) not treated with nicotine but challenged with TNFα for 1 hour prior to analysis. A set of cells were not pre-treated with EGCG and 5) treated for 24 hours with 0.1 mM nicotine prior to challenge with 10 ng/ml TNFα for 1 hour, or 6) not treated with nicotine but challenged with TNFα for 1 hour prior to analysis. TNFα was used in conjunction with nicotine because in addition to playing a role in periodontal disease, the proinflammatory cytokine TNFα can upregulate cytokines such as IL-1α and IL-6[21]. This was done to model for smokers who may also be experiencing an inflammatory reaction.

Culture medium samples were assayed for levels of secreted IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 using the protocols provided with individual ELISA kits (RnD Systems Quantikine ELISA kits, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Absorbance were read at 450 nm and interleukin concentrations were calculated using the appropriate standard curve. All experimental values were within the assay ranges of each interleukin kit.

Prior to concentration calculations, absorbance were standardized to total cell number in the tissue culture wells using crystal violet blue staining. Adherent cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet blue stain. Stained cells were eluted with 1% SDS solution, and absorbance were read at 595 nm. Corrections were calculated by dividing the OD 450 nm for a given well by the OD 595 nm reading of the same well. Statistical analysis was completed for individual interleukins using ANOVA and Tukey post-test with probability set at p < 0.05. ELISA studies were repeated three times.

Results

Levels of a panel of interleukins in culture medium were assayed to determine the effect of EGCG on the inflammatory process in nicotine-challenged human gingival epithelial cells.

Interleukins IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-8

IL-4 concentrations in all control and experimental culture medium samples were below the detection level of the ELISA (data not shown). Levels of all interleukins in control cells with no treatment of any kind, or treatment with EGCG only were less than 50 pg/ml. Control values are shown for each interleukin assayed.

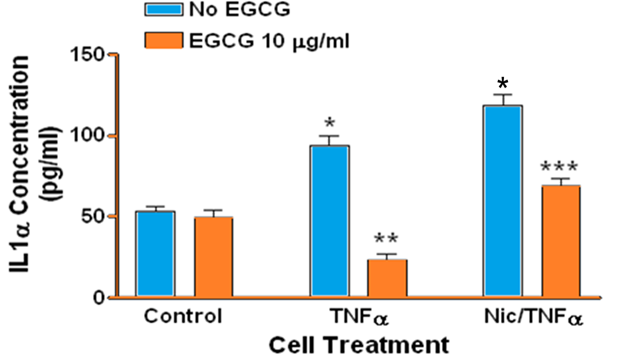

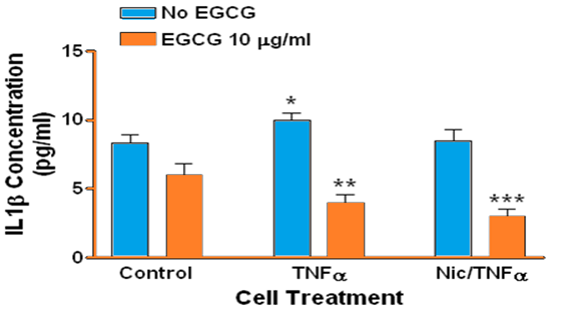

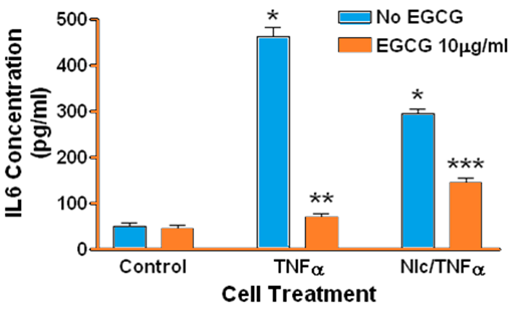

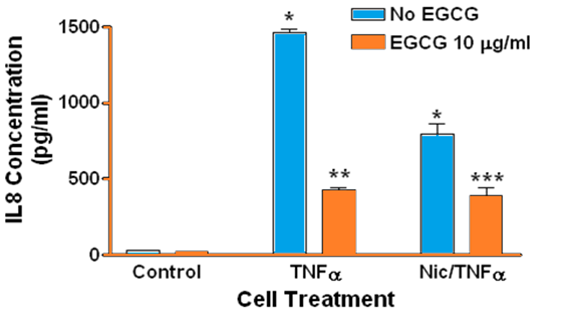

Treatment of human gingival epithelial cells with TNFα alone or with a combination of nicotine and TNFα resulted in increased secretion of IL-1α IL-1β IL-6, and IL-8 into the culture medium, although to different degrees compared to controls and to each treatment. Specifically, there was no difference in the level of IL-1α (Figure 1) β or IL-1β (Figure 2) in culture medium when comparing TNFα to combined TNFα and nicotine treatments. In contrast TNFα alone resulted in significantly more IL-6 (Figure 3) and IL-8 (Figure 4) secretion into culture medium compared to combined TNFα and nicotine treatment (p < 0.001 for both interleukins).

Figure 1: Secretion of IL-1α by human gingival epithelial cells. (*, blue bars): Treating cells with TNFα or combined nicotine and TNFα (Nic/TNFα) significantly increased secretion of IL-1α compared to control (p < 0.001). (**): Treating cells with EGCG prior to TNFα significantly decreased IL-1α secretion compared to cells treated with TNFα only (p < 0.001). (***): Treating cells with EGCG prior to combined nicotine and TNFα challenge significantly decreased IL-1α secretion compared to cells treated with combined nicotine and TNFα only (p < 0.001).

Figure 2: Secretion of IL-1α by human gingival epithelial cells. (*, blue bars): Treating cells with TNFα significantly increased secretion of IL-1α compared to control (p = 0.0056). (**): Treating cells with EGCG prior to TNFα significantly decreased IL-1α secretion compared to cells treated with TNFα only (p < 0.001). (***): Treating cells with EGCG prior to combined nicotine and TNFα (Nic/TNFα) challenge significantly decreased IL-1α secretion compared to cells treated with combined nicotine and TNFα only (p < 0.001). Note that IL-1α secretion in EGCG-treated cells is below control levels.

Figure 3: Secretion of IL-6 by human gingival epithelial cells. (*, blue bars): Treating cells with TNFα or combined nicotine and TNFα(Nic/TNFα) significantly increased secretion of IL-6 compared to control (p < 0.001). (**): Treating cells with EGCG prior to TNFα significantly decreased IL-6 secretion compared to cells treated with TNFα only (p < 0.0001). (***): Treating cells with EGCG prior to combined nicotine and TNFα challenge significantly decreased IL-6 secretion compared to cells treated with combined nicotine and TNFα only (p < 0.001).

Figure 4: Secretion of IL-8 by human gingival epithelial cells. Note that IL-8 secretion is barely detectable in controls. (*, blue bars): Treating cells with TNFα or combined nicotine and TNFα (Nic/TNFα) significantly increased secretion of IL-8 compared to control (p < 0.0001). (**): Treating cells with EGCG prior to TNFα significantly decreased IL-8 secretion compared to cells treated with TNFα only (p < 0.0001). (***): Treating cells with EGCG prior to combined nicotine and TNFα challenge significantly decreased IL-8 secretion compared to cells treated with combined nicotine and TNFα only (p < 0.01).

ECGC significantly suppressed the secretion of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 in gingival epithelial cells treated with TNFα (p < 0.001 for all interleukins). Similarly, EGCG significantly suppressed the secretion of IL-1α IL-1β IL-6, and IL-8 in gingival epithelial cells treated with combined TNFα and nicotine (p < 0.01 for all interleukins). For several treatments interleukin levels were reduced below those of controls in the presence of EGCG.

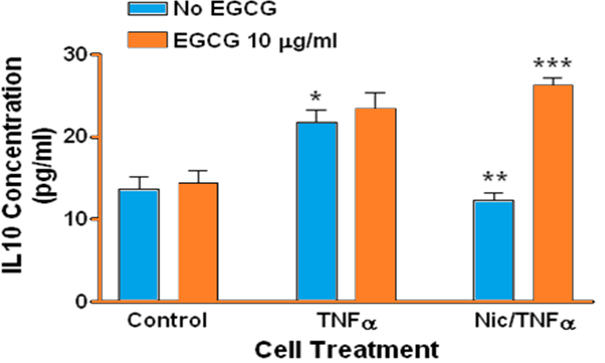

Interleukin IL-10

Treating human gingival epithelial cells with TNFα resulted in significantly increased IL-10 in the culture medium (p < 0.001, Figure 5), however EGCG did not reduce IL-10 in TNFα-treated cells. The presence of nicotine in TNFα-treated cells significantly reduced IL-10 secretion into culture medium (p < 0.001). However again EGCG did not reduce IL-10 levels but in contrast significantly increased secretion in combined TNFα and nicotine treated cells (p < 0.001)

Figure 5: Secretion of IL-10 by human gingival epithelial cells. (*, blue bars): Treating cells with TNFα significantly increased secretion of IL-10 compared to control (p < 0.001). A similar result was not observed for cells treated with combined nicotine and TNFα (Nic/TNFα). (**): Treating cells with combined nicotine and TNFα significantly decreased IL-10 secretion compared to cells treated with TNFα only (p < 0.001). (***): Treating cells with EGCG prior to combined nicotine and TNFα challenge significantly increased IL-10 secretion compared to cells treated with combined nicotine and TNFα only (p < 0.001).

Discussion

The effect of cigarette compounds on pro-inflammatory interleukin production has been observed both in vivo and in vitro. In human volunteers with experimental gingivitis a significantly higher amount of baseline IL-8 was detected in smokers compared to non-smokers[5]. Cultured gingival keratinocytes and fibroblasts exposed to nicotine secrete significantly higher levels of IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8[3,6,22]. The present study agrees with other reports that the presence of nicotine results in the stimulation of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8. Conversely nicotine did not affect IL-4 release by peripheral blood mononuclear cells or T cell clones[23] and low to undetectable levels of IL-4 were observed in a human population with periodontitis[8]. In agreement, the present study demonstrates that nicotine did not upregulate the secretion of IL-4 in gingival epithelial cells.

The results reported in this current study support and extend the work by other authors that nicotine, the major component of cigarette smoke, can upregulate the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in oral cells. Many studies analyzing the oral mucosa use fibroblasts as the model, this study is one of the few that have utilized epithelial cells. Epithelial cells line the oral cavity and are not embedded within connective tissues as are fibroblasts. Gingival epithelial cells would be in direct contact with cigarette components in a smoker and are therefore a preferred cell type when developing an in vitro model of nicotine- induced inflammation in the oral cavity.

A recent study suggested that EGCG may be useful in the prevention and treatment of smoking?associated non-small cell lung carcinoma[24]. Additionally, EGCG may inhibit the nicotine-induced invasive character of human endothelial cells[25]. In contrast, a PubMed search revealed that there are no studies reporting the effects of EGCG on nicotine-induced IL-1, IL-6 and/or IL-8 secretion in oral cells. The study herein thus presents novel data suggesting that EGCG can function as an anti-inflammatory agent in human gingival epithelial cells, suggesting its usefulness to combat the deleterious effects of nicotine and smoking on oral health.

IL-10 is also known as the cytokine synthesis inhibiting factor (CSIF) and controls inflammatory processes by suppressing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules[26]. In essence it is an anti-inflammatory cytokine. In human gingival epithelial cells challenged with both TNFα and nicotine, EGCG significantly stimulated the release of IL-10. Similarly to the pro-inflammatory cytokines, there are no published studies reporting the effect of EGCG on nicotine-induced IL-10 secretion in oral cells; this is the first study to report that EGCG may induce anti-inflammatory cytokines under conditions of inflammation. EGCG may function to regulate multiple cellular pathways to suppress inflammation. In human dental pulp cells, catechins including EGCG inhibited MAPK phosphorylation and suppressed NF?B activation, suggesting that catechins might be useful therapeutically as an anti-inflammatory modulator of dental pulpal inflammation[27]. Additional studies must be completed to determine if the ability of catechins to dampen inflammatory responses is cell-universal.

Tea is globally available and well accepted; EGCG is inexpensive to isolate from tea and therefore could be administered orally as a drug or nutrient. One must question if smokers would consume tea and/or EGCG post-cigarette use as an anti-inflammatory agent. In this study, EGCG was presented to cells prior to nicotine administration to model for the smoker who is also a tea drinker. EGCG would be present in the oral cavity or circulating in the system as the smoker was delivering nicotine to the body.

In vitro observations must be taken to the in vivo correlate with extreme caution and this represents the main limitation of this current study. Many in vivo studies use concentrations of EGCG that are well above biological availability. Drinking 5 to 6 cups of green tea a day resulted in a blood serum concentration of EGCG of approximately 1 μM[28] suggesting that physiological concentrations of EGCG are in the range of 0.1-1.0 μM[29]. Although a daily dose of 800 mg of caffeine-free EGCG for four weeks (8 to 16 cups of green tea) was well-tolerated[30] EGCG and other phenolic compounds may be hepatotoxic at high doses[31]. In vivo studies must be reviewed carefully if they are to serve as a rationale for the clinical or therapeutic use of green tea and EGCG.

Conclusion

In an in vitro model of nicotine and TNFα-induced inflammation in human gingival epithelial cells, the tea catechin EGCG inhibited the secretion of pro-inflammatory interleukins and enhanced the secretion of an anti-inflammatory cytokine. EGCG and green tea may be useful in suppressing oral mucosal inflammation in the smoker.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by an internal grant from the University of Detroit, Mercy School of Dentistry.

References

- 1. Tomar, S. L., Asma, S. Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: Findings from NHANES III. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. (2000) J Periodontol 71(5): 743- 751.

- 2. James, J. A., Sayers, N. M., Drucker, D. B., et al. Effects of the tobacco products on the attachment and growth of periodontal ligament fibroblasts. (1999) J Periodontol 70(5): 518- 525.

- 3. Wendell, K. J., Stein, S. H. Regulation of cytokine production in human gingival fibroblasts following treatment with nicotine and lipopolysaccharide. (2001) J Periodontology 72(8): 1038- 1044.

- 4. Mahanonda, R., Sa-Ard-Iam, N., Eksomtramate, M., et al. Cigarette smoke extract modulates human b-defensin-2 and interleukin-8 expression in human gingival epithelial cells. (2009) J Periodontal Res 44(4): 557- 564.

- 5. Giannopoulou, C., Cappuyns, I., Mombelli, A. Effect of smoking on gingival crevicular fluid cytokine profile during experimental gingivitis. (2003) J Clin Periodontol 30(11): 996- 1002.

- 6. Johnson, G. K., Guthmiller, J. M., Joly, S., et al.Interleukin-1 and interleukin-8 in nicotine- and lipopolysaccharide-exposed gingival keratinocyte cultures. (2010) J Periodontal Res 45(4): 583– 588.

- 7. Almasri, A., Wisithphrom, K., Windsor, L. J., et al. Nicotine and lipopolysaccharide affect cytokine expression from gingival fibroblasts. (2007) J Periodontol 78(3): 533- 541.

- 8. Duarte, P. M., da Rocha, M., Sampaio, E., et al. Serum levels of cytokines in subjects with generalized chronic and aggressive periodontitis before and after non-surgical periodontal therapy: a pilot study. (2010) J Periodontol 81(7): 1056- 1063.

- 9. Narotzki, B., Reznick, A. Z., Aizenbud, D., et al. Green tea: a promising natural product in oral health. (2012) Arch Oral Biol 57(5): 429- 435.

- 10. Lee, K. W., Lee, H. J., Lee, C. Y. Antioxidant activity of black tea vs. green tea. (2002) J Nutr 132(4): 785.

- 11. Nakanishi, T., Mukai, K., Yumoto, H., et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of catechin on cultured human dental pulp cells affected by bacteria-derived factors. (2010) Eur J Oral Sci 118(2): 145- 150.

- 12. Yosokawa, Y., Hosokawa, I., Ozaki, K., et al. Catechins inhibit CCL20 production in IL-17A stimulated human gingival fibroblasts. (2009) Cell Physiol Biochem 24(5-6): 391- 396.

- 13. Ahmed, S., Rahman, A., Hasnain, A., et al. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits the IL-1 beta-induced activity and expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and nitric oxide synthase-2 in human chondrocytes. (2002) Free Radic Biol Med 33(8): 1097– 1105.

- 14. Ichikawa, D., Matsui, A., Imai, M., et al. Effect of various catechins on the IL-12p40 production by murine peritoneal macrophages and a macrophage cell line, J774.1. (2004) Biol Pharm Bull 27(9): 1353– 1358.

- 15. Shin, H. Y., Kim, S. H., Jeong, H. J., et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits secretion of TNF-alpha, IL-6 and IL-8through the attenuation of ERK and NF-kappaB in HMC-1 cells. (2007) Int Arch Allergy Immunol 142(4): 335– 344.

- 16. Wang, J., Pae, M., Meydani, S. N., et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits expression of receptors for T cell regulatory cytokines and their downstream signaling in mouse CD4+ T cells. (2012) J Nutr 142(3): 566- 571.

- 17. Sergent, T., Piront, N., Meurice, J., et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of dietary phenolic compounds in an in vitro model of inflamed human intestinal epithelium. (2010) Chem Biol Interact 188(3): 659- 667.

- 18. Tipoe, G. L., Leung, T. M., Liong, E. C., et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) reduces liver inflammation, oxidative stress and fibrosis in carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver injury in mice. (2010) Toxicology 273(1-3): 45- 52.

- 19. Bae, H. B., Li, M., Kim, J. P., et al. The effect of epigallocatechingallate on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in a murine model. (2010) Inflammation 33(2): 82- 91.

- 20. Hosokawa, Y., Hosokawa, I., Ozaki, K., et al. Tea polyphenols inhibit IL-6 production in tumor necrosis factor superfamily 14-stimulated human gingival fibroblasts. (2010) MolNutr Food Res 54 (Suppl 2): S151- S158.

- 21. Garlet, G. P. Destructive and protective roles of cytokines in periodontitis: a re-appraisal from host defense and tissue destruction viewpoints (2010) J Dent Res 89(12): 1349- 1363.

- 22. Johnson, G K., Organ, C. C. Prostaglandin E2 and interleukin-1 concentrations in nicotine-exposed oral keratinocyte cultures (1997) J Periodont Res 32(5): 447- 454.

- 23. Le Cam, L., Lagier, B., Bousquet, J., et al.Nicotine does not modulate IL-4 and interferon-gamma release from peripheral blood mononuclear cells and T cell clones activated by phorbolmyristate acetate and calcium ionophore. (1996) Int Arch Allergy Immunol 111(4): 372- 375.

- 24. Shi, J., Liu, F., Zhang, W., et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits nicotine?induced migration and invasion by the suppression of angiogenesis and epithelial?mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancer cells. (2015) Oncol Rep 33(6): 2972- 2980.

- 25. Khoi, P. N., Park, J. S., Kim, J. H., et al.(-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate blocks nicotine-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression and invasiveness via suppression of NF-κB and AP-1 in endothelial cells. (2013) Int J Oncol 43(3): 868- 876.

- 26. Asadullah, K., Sterry, W., Volk, H. D. Interleukin-10 therapy-review of a new approach. (2003) Pharmcol Rev 55(2): 241- 269.

- 27. Hirao, K.,Yumoto, H., Nakanishi, T., et al. Tea catechins reduce inflammatory reactions via mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in toll-like receptor 2 ligand-stimulated dental pulp cells. (2010) Life Sci 86(17-18): 654-660.

- 28. Lee, M. J., Maliakal P, Chen L, et al. Pharmacokinetics of tea catechins after ingestion of green tea and (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate by humans: formation of different metabolites and individual variability. (2002) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11(10 Pt 1): 1025- 1032.

- 29. Ellis, L. Z., Liu, W., Luo, Y., et al. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate suppresses melanoma growth by inhibiting inflammasome and IL-1β secretion (2011) Biochem Biophys Res Commun 414(3): 551- 556.

- 30. Chow, H.H., Cai, Y., Hakim, I.A., et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of green tea polyphenols after multiple-dose administration of epigallocatechingallate and polyphenon E in healthy individuals. (2003) Clin Cancer Res 9(9): 3312– 3319.

- 31. Galati, G., Lin, A., Sultan, A.M., et al. Cellular and in vivo hepatotoxicity caused bygreen tea phenolic acids and catechins. (2006) Free Radic Biol Med 40(4): 570- 580.