Essential Fatty Acid Deficiency in Very Long-Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficient Patients

Eugene F. Diekman1,2, Jeannette C. Bleeker1,2, Merel R. van Veen2, Ronald J. Wanders1, Sander M. Houten1, Frits Wijburg1, Frédéric M. Vaz1, Gepke Visser2*

Affiliation

- ¹Laboratory Genetic Metabolic Diseases, Departments of Clinical Chemistry, and Pediatrics, Emma Children's Hospital, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands

- ²Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Metabolic Diseases, Wilhelmina Children's Hospital Utrecht, University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Corresponding Author

Gepke Visser, Department of Gastroenterology and metabolic disease Wilhelmina Children\'s Hospital, KC 03.063.0, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Lundlaan 6, 3584 EA, Utrecht, Tel: 0031887554003; Fax: 0031887555350; E-mail: gvisser4@umcutrecht.nl

Citation

Visser, G., et al. Essential Fatty Acid Deficiency In Very Long-Chain Acyl-Coa Dehydrogenase Deficient Patients (2014) J Food Nutr Sci 1(1): 27-30.

Copy rights

©2015 Visser, G. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Essential fatty acid deficiency; Very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency; VLCADD; Mead acid; linoleic acid; long-chain triglyceride restriction.

Abstract

Introduction: Very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (VLCADD), a long-chain fatty acid (LCFA) beta-oxidation disorder, may be treated with LCFA restriction. As Essential Fatty Acids (EFAs) are LCFAs, patients may be at risk for EFA deficiency.

Objectives: Investigate whether LCFA restrictions lead to EFA deficiency in VLCADD and which markers are indicative of EFA deficiency.

Methods: Thirty-nine LCFA profiles of 16 VLCADD patients were determined in erythrocytes and compared to 48 healthy controls. The predictive value of EFA deficiency markers was calculated from data of a historic cohort (n = 4523, 0-39yrs).

Results: Linoleic acid (LA), dihomo-γ-linolenic acid (DHLA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) were significantly decreased in VLCADD patients. Patients on docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid (AA) supplementation exhibited even lower LA. Mead acid, a presumed marker for EFA-deficiency, was not increased in patients. In the historic cohort, sensitivity of MA was low for LA deficiency (24% for levels < 2.5 percentile) and for DHA+AA deficiency (12% for levels < 2.5 percentile).

Discussion: VLCADD patients on LCFA restriction are prone to develop LA deficiency. Furthermore, MA is a specific, but not a sensitive marker for LA or EFA deficiency, neither in VLCADD patients, nor in healthy controls, nor in a large patient cohort.

Introduction

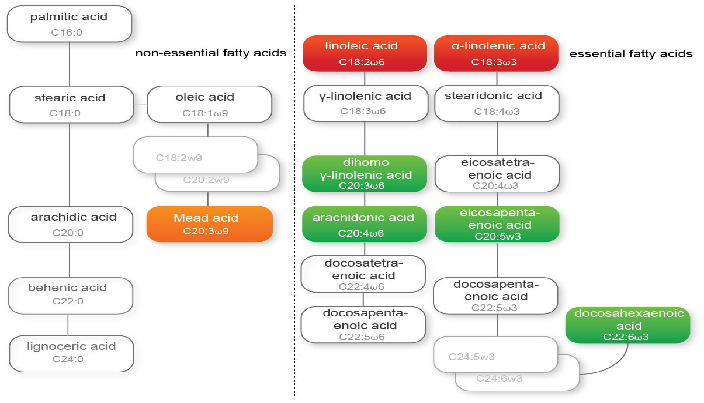

Due to the abundant availability of essential fatty acids (EFAs) in the Western diet, EFA deficiency is uncommon in healthy individuals[1]. In case of disease, or if the intake of EFAs is severely diminished, EFA deficiency may occur, because humans cannot synthesize linoleic acid (LA; C18:2ω6) and alfa- linolenic acid (ALA; C18:3ω3) and are therefore fully dependent on dietary intake of these two, true EFAs[2]. Other, (semi-) essential fatty acids, can be synthesized de novo, but in limited amounts only (figure 1)[3,4]. For example, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; C22:6ω3) is synthesized for < 0.1% from ALA[3]. All EFAs are poly-unsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) and have several double bonds in their carbon chain. The position at which the first double bond is situated is called ω, followed by a number.

Figure 1: 'EFA synthesis pathway' A schematic representation of the various fatty acid and EFA synthesis pathways per omega fatty acid. From left to right: unsaturated, omega-9, omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids. M/PUFA = mono-/ polyunsaturated fatty acids; LCPUFA = long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids; Red = essential fatty acids, dietary need; Green = important essential fatty acids; orange = surrogate marker for EFA deficiency.

EFAs are involved in several important physiological and pathological processes. As components of complex lipids, they play a crucial role in physicochemical properties of cell membranes and thereby influence cell integrity and function[4,5]. EFAs are precursors for the synthesis of prostaglandins, leukotriene's and thromboxane's[2,4,6-8]. Furthermore, LA is important for elasticity of the skin and immunity[4] and high LA intake may reduce the risk for coronary heart disease[9]. Finally DHA, synthesized from ALA[4], is a major fatty acid component of the grey matter of the cerebral cortex and of the photoreceptor of the tina[1,4,5,].

In case of EFA deficiency 'surrogate' fatty acids are synthesized, probably as a substitute for the lack of unsaturated fatty acids. Normally, if EFAs are available, Δ6 as well as Δ5 and Δ4 desaturases accept ω3 and ω6 EFAs. When EFAs are deficient in ω3 and ω6 EFAs, these desaturases also handle ω9 fatty acids, such as oleic acid (OA; C18:1ω9) to form Mead Acid (MA; C20:3ω9)[10-12]. An increased MA level has therefore been suggested to be a marker for EFA deficiency[11]. Another marker used to describe EFA status, is the EFA status index (EFASTI). The EFASTI is defined as the ratio between the sum of the ω3 and ω6 fatty acids and the sum of the ω7 and ω9 fatty acids[13].

Very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (VLCADD), is an inherited disorder of long-chain fatty acid beta-oxidation (OMIM 609575) in which energy homeostasis is compromised. Patients may develop hypoglycaemia, rhabdomyolysis, hepatomegaly and (cardio)myopathy[14-16]. Treatment consists of dietary measures aimed at maintaining energy homeostasis including frequent meals and for some patients also a long-chain fatty acid restricted diet[17]. Since EFAs are long-chain fatty acids, patients on a long-chain fatty acid restricted diet are at risk for developing EFA deficiency. We investigated whether VLCADD patients are EFA deficient as a consequence of the dietary restrictions. In addition, we investigated whether specific markers are indicative of EFA deficiency.

Materials and Methods

Quantitative analysis of erythrocyte fatty acid profiles in erythrocytes was performed by gas chromatography of fatty acid methyl ester and detection using flame ionisation detection as previously described[18]. Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA (with Dunns post-test) were used to test significance. Prism software (version 5.0, Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for statistical analysis.

Samples were analysed of 16 VLCADD patients; 8 females and 8 males, age range 2-39 yrs. Diagnosis was confirmed in all by molecular analysis of the ACADVL gene. A total of 39 samples were analysed, with a maximum of 5 sequential measurements per patient, and a minimal time interval of 6 months between measurements.

Dietary analysis based on a 3-day diary and a subsequent questionnaire by a nutritionist on the day the final EFA sample was taken, was performed in 15 out of 16 patients. LCT restriction was defined as an intake of fat < 25% of energy intake En%. If patients used DHA/AA supplementation the standard dosage was 100mg DHA and 200mg AA.

To determine the overall EFA-status in VLCADD patients, all samples were included. For calculating the predictive value of MA and the EFASTI in VLCADD patients, also all EFA measurements were used.

Control samples were obtained from 48 healthy individuals. In addition, data of a large cohort of patients whose fatty acid status was evaluated in the laboratory Genetic Metabolic Diseases from 1993 until 2010 (n = 4523, 0-39yrs) was used to calculate the predictive value of MA and the EFASTI.

Results

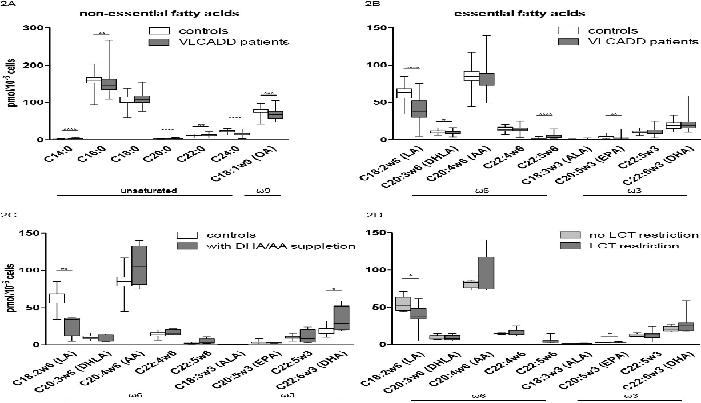

The used reference values for PUFAs are shown in table 1. Non-essential saturated, mono-unsaturated and PUFAs measurements of the VLCADD patients were compared to measurements of the control population. As is shown in figure 2A VLCADD patients had an increased myristic acid (C14:0), eicosanoic acid (C20:0) and behenic acid (C22:0) compared to controls, whereas palmitic acid (C16:0), oleic acid (C18:1ω9) and lignoceric acid (C24:0) were significantly decreased.

Table 1: Reference values PUFA and EFA's'

| n = 48 | Mean | Std. dev | 0.025 Percentile | 0.975 Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C14:0 | 2,4 | 0,5 | 1,62 | 3,3 |

| C15:0 | 1,45 | 0,3 | 1 | 2,07 |

| C16:0 | 160,08 | 19,2 | 131,96 | 190,04 |

| C18:0 | 106,74 | 13,05 | 90,84 | 127,74 |

| C20:0 | 3,06 | 0,44 | 2,52 | 3,88 |

| C22:0 | 10,55 | 1,5 | 8,09 | 12,87 |

| C24:0 | 22,51 | 3,2 | 18,52 | 27,72 |

| C18:3w3 | 0,81 | 0,2 | 0,5 | 1,28 |

| C20:5w3 | 3,29 | 1,5 | 1,65 | 7,12 |

| C22:5w3 | 10,34 | 2 | 6,97 | 14,02 |

| C22:6w3 | 18,93 | 4,95 | 11,24 | 26,58 |

| C18:2w6 | 63,34 | 10,01 | 47,41 | 79,95 |

| C20:3w6 | 10,43 | 2,51 | 6,65 | 15,75 |

| C20:4w6 | 84,69 | 11,57 | 71,34 | 103,61 |

| C22:4w6 | 14,19 | 2,94 | 10,52 | 19,29 |

| C22:5w6 | 2,32 | 0,67 | 1,24 | 3,57 |

Figure 2: A-D 'EFA levels in VLCADD patients' Control samples n = 48 and VLCADD patient samples n = 39. Mann-Whitney U test for significance. Box-plot, with median and 1,5 quartiles. OA = oleic acid; MA = Mead acid; LA = linoleic acid; DHLA = di-homo-γ-linolenic acid; AA = arachidonic acid; ALA = alpha-linolenic acid; EPA = eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA = docosahexaenoic acid. A) non-essential unsaturated and ω9 fatty acids. B) essential ω6 and ω3 fatty acids. C) EFA concentrations of controls (n = 48) and VLCADD patients on DHA/AA supplementation (n = 4). D) EFA concentrations of VLCADD patients with (n = 5) or without LCT restriction (n = 10).

Of all EFAs, LA, DHLA and EPA were significantly decreased in VLCADD patients compared to controls (figure 2B). Twenty-five out of 39 EFA measurements (11 patients) had a LA concentration below 2.5 percentile. Six out of 39 (6 patients) had a DHLA level below 2.5 percentile and 7 out of 39 (5 patients) had an EPA level below 2.5 percentile. In contrast, docosapentaenoic acid (C22:5ω6) was significantly increased in patients with VLCADD compared to controls. ALA and other EFAs such as AA and DHA were not significantly different compared to controls, but were low to extremely low in individual patients.

Figure 2C shows that VLCADD patients on DHA/AA supplementation have significantly lower LA values compared to controls and significantly higher DHA values. LCT restriction in VLCADD patients did not result in an overall EFA-deficiency, but did lead to decreased LA values (figure 2D). EPA was slightly increased in patients upon LCT restriction.

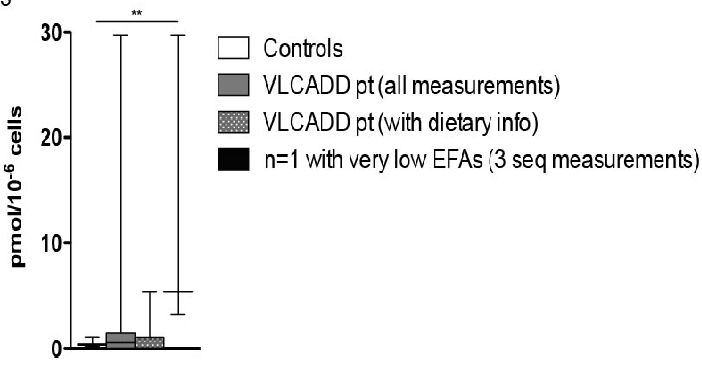

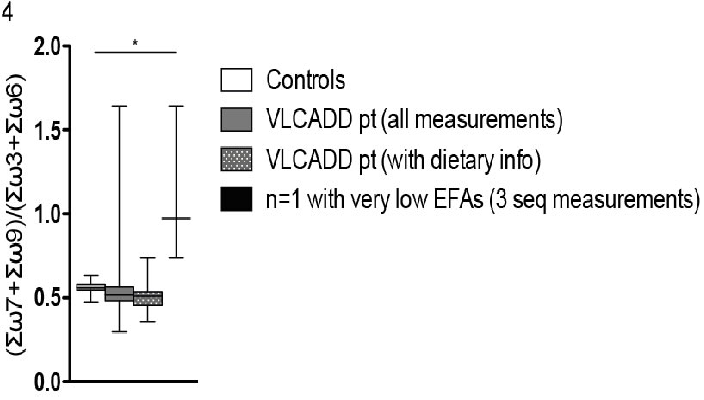

MA was not increased in VLCADD patients in general (figure 3). However, MA was high in one VLCADD patient who had an extremely low LA (< 7.8 pmol/10-6 cells). The same phenomenon was observed in the large patient cohort: 621 individuals had a LA < 2.5 percentile, but only 150 had an increased MA (sensitivity 24%). In addition, 480 individuals had a DHA+AA level < 2.5 percentile, but only 58 had an increased MA (sensitivity 12%). The EFASTI did not reveal an increase in ω7 and ω9 (figure 4) in VLCADD patients compared to controls, except for the overall EFA-deficient patient. However, the EFASTI level was high in a single VLCADD patient who had a number of EFAs < 2.5 percentile (including an extremely low LA (< 7.8 pmol/10-6 cells)).

Figure 3: 'Mead acid levels in VLCADD patients' MA levels in controls (n = 48), VLCADD patients (all measurements, n = 39; measurements with dietary data, n = 15) and an EFA deficiency VLCADD patient (n = 1, 3 samples). Krukis-Wallis test (with Dunns post-test) for significance.

Figure 4: 'EFASTI' EFASTI (Essential Fatty-Acid Status Index) in controls (n = 48), VLCADD patients (all measurements, n = 39; measurements with dietary data, n = 15) and an EFA deficiency VLCADD patient (n = 1, 3 samples). Krukis-Wallis test (with Dunns post-test) for significance.

Discussion

This study shows that compared to healthy controls, all VLCADD patients are more prone to develop LA, DHLA and EPA deficiency. In addition, more EFAs can also be (severely) deficient when LCADD patients are on a LCT restricted diet. The reason for the low concentrations of LA in all VLCADD patients is yet unclear as the role of VLCAD in EFA metabolism is limited. Mitochondrial β-oxidation involves a cascade of enzymes, which break down long-chain fatty acids. VLCAD is the first enzyme in this cascade. Without VLCAD, long-chain fatty acids such as C14-18:0; C14:1-18:1, and C14:2-C18:2(ω6) cannot be metabolised[19]. In this study, however, a decreased C18:2 (ω6) concentrations were found in VLCADD patients. This might in part be caused by dietary LCT restriction, since patients on a diet with LCT-restriction had significantly lower LA levels compared to patients without LCT restriction (figure 2D). Moreover, the studied erythrocyte fatty acid composition of EFA is supposed to reflect long term dietary fatty acid intake better than plasma concentrations[20].

In contrast to the decreased LA concentrations, ALA is not significantly decreased in VLCADD patients and no difference is found between LCT restricted and non-restricted patients. Furthermore, despite DHA/ AA supplementation resulting in normal DHA and AA levels in patients, LA remains deficient (figure 2C). Whether the observed changes in EFAs are due to the altered fat metabolism in VLCADD and/or a specific dietary LA restriction needs further investigation.

LA deficiency is associated with skin abnormalities, increased susceptibility to infection and poor growth[4,21]. Although the latter two have been observed in some VLCADD patients, the majority of patients did not experience an apparent short-term functional deficit.

It is suggested that certain markers such as MA and the EFASTI might reveal EFA deficiency[11,13]. In our large historic patient cohort we investigated the value of both markers (supplemental table 1A and B) and found that MA and EFASTI are specific, but not sensitive markers for LA deficiency (defined as LA < 2.5 percentile) or EFA deficiency (defined as a DHA+AA level < 2.5 percentile). EFA levels of the VLCADD patients and controls were also compared with both markers. In VLCADD patients LA-deficiency was not enough to increase production of MA, or lead to a difference in EFASTI (Figure 3 and Figure 4). However, both markers are indeed abnormal in a severely EFA deficient VLCADD patient (Figure 4).

S1A

LA vs low ref. MA in patient cohort

| disease (LA < 2.5 percentile) | no disease (LA > 2.5 percentile) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pos. (MA > 97.5 percentile | 150 | 242 | 392 |

| neg. (MA < 97.5 percentile | 471 | 3660 | 4131 |

| 621 | 3902 | 4523 |

| PPV = A/(A+B) | 0.38 |

|---|---|

| NPV = D/(C+D) | 0.89 |

| Se = A/(A+C) | 0.24 |

|---|---|

| Sp = D/(B+D)) | 0.94 |

S1B

DHA + AA vs low ref. MA in patient cohort

| disease (LA < 2.5 percentile) | no disease (LA > 2.5 percentile) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pos. (MA > 97.5 percentile | 58 | 220 | 278 |

| neg. (MA < 97.5 percentile | 278 | 2304 | 2726 |

| 480 | 2524 | 3004 |

| PPV = A/(A+B) | 0.21 |

|---|---|

| NPV = D/(C+D) | 0.85 |

| Se = A/(A+C) | 0.12 |

|---|---|

| Sp = D/(B+D)) | 0.91 |

Supplemental Table 1A-B:A) LA deficiency vs MA levels. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV (positive predictive value), NPV (negative predictive value) in control group. B) DHA and AA deficiency vs MA. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV (positive predictive value), NPV (negative predictive value) in control group.

In conclusion, VLCADD patients are prone to become LA deficient. Furthermore, MA is a specific but not a sensitive marker for LA and EFA-deficiency in VLCADD patients.

Conflict of interest: Eugene Diekman, Jeannette Bleeker, Merel van Veen, Ronald Wanders, Sander Houten, Frédéric Vaz, Frits Wijburg and Gepke Visser declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements: Funding: Eugene Diekman is paid by a grant of ZonMW (The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development, dossier 200320006) and Metakids.

References

- 1. Konner, M., Eaton, S.B. Paleolithic nutrition: twenty-five years later. (2010) Nutr Clin Pract 25(6): 594-602.

- 2. Bézard, J., Blond, J.P., Bernard, A., et al. The metabolism and availability of essential fatty acids in animal and human tissues. (1994) Reprod Nutr Dev 34(6): 539-568.

- 3. Harris, W.S., Mozaffarian, D., Lefevre, M., et al., Towards establishing dietary reference intakes for eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids. (2009) J Nutr 139(4): 804S–819S.

- 4. Youdim, K.A., Martin, A., Joseph, J.A. Essential fatty acids and the brain: possible health implications. (2000) Int J Dev Neurosci 18(4-5): 383-399.

- 5. Innis, S.M. Omega-3 Fatty acids and neural development to 2 years of age: do we know enough for dietary recommendations? (2009) J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 48(1): S16–S24

- 6. Van, Dorpd., Beerthuis, R.k., Nugteren, D.H., et al. The biosynthesis of prostaglandins. (1964) Biochim Biophys Acta 90: 204-207.

- 7. Olsen, S.F., Hansen, H.S., Sørensen, T.I., et al., Intake of marine fat, rich in (n-3)-polyunsaturated fatty acids, may increase birthweight by prolonging gestation. (1986) Lancet 2(8503): 367–369.

- 8. Goodnight, S.H., Harris, W.S., Connor, W.E., et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, hyperlipidemia, and thrombosis. (1982) Arteriosclerosis 2(2): 87–113.

- 9. 9. Harris, W.S., Mozaffarian, D., Rimm, E., et al., Omega-6 fatty acids and risk for cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Nutrition Subcommittee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. (2009) Circulation 119(6): 902-907.

- 10. Siguel, E.N., Chee, K.M., Gong, J.X., et al. Criteria for essential fatty acid deficiency in plasma as assessed by capillary column gas-liquid chromatography. (1987) Clin Chem 33(10): 1869-1873.

- 11. Fokkema, M.R., Smit, E.N., Martini, I.A., et al. Assessment of essential fatty acid and omega3-fatty acid status by measurement of erythrocyte 20:3omega9 (Mead acid), 22:5omega6/20:4omega6 and 22:5omega6/22:6omega3. (2002) Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 67(5): 345-356.

- 12. Mead, J.F. The metabolism of the essential fatty acids. (1958) Am J Clin Nutr 6(6): 656-661.

- 13. Vlaardingerbroek, H., Hornstra, G., de Koning, T.J., et al., Essential polyunsaturated fatty acids in plasma and erythrocytes of children with inborn errors of amino acid metabolism. (2006) Mol Genet Metab 88(2) 159-165.

- 14. Vianey-Saban, C., Divry, P., Brivet, M., et al., Mitochondrial very-long-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency: clinical characteristics and diagnostic considerations in 30 patients. (1998) Clin Chim Acta 269(1): 43-62.

- 15. Laforêt, P., Acquaviva-Bourdain, C., Rigal, O., et al., Diagnostic assessment and long-term follow-up of 13 patients with Very Long-Chain Acyl-Coenzyme A dehydrogenase (VLCAD) deficiency. (2009) Neuromuscul Disord 19(5): 324-329.

- 16. Spiekerkoetter, U. Mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation disorders: clinical presentation of long-chain fatty acid oxidation defects before and after newborn screening. (2010) J Inherit Metab Dis 33(5): 527-532.

- 17. Arnold, GL., Van Hove, J., Freedenberg, D., et al. A Delphi clinical practice protocol for the management of very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. (2009) Mol Genet Metab 96(3): 85-90.

- 18. Dacremont, G., Vincent, G. Assay of plasmalogens and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) in erythrocytes and fibroblasts. (1995) J Inherit Metab Dis 18 (1): 84-89.

- 19. Houten, S.M., Wanders, R.J. A general introduction to the biochemistry of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation. (2010) J Inherit Metab Dis 33(5): 469-477.

- 20. Katan, M.B., Deslypere, J.P., van Birgelen, A.P., et al. Kinetics of the incorporation of dietary fatty acids into serum cholesteryl esters, erythrocyte membranes, and adipose tissue: an 18-month controlled study. (1997) J Lipid Res 38(10): 2012–2022.

- 21. Fernandes, J. Nutrition and health--recommendations of the Health Council of the Netherlands regarding energy, proteins, fats and carbohydrates. (2002) Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 146(47): 2226-2229.