Exploring Patients Perceptions of Their Surgeon Based on Attire

Sebastien Lalonde1 , Stephanie Cudd2

Affiliation

- 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Kingston General Hospital, Queens University, Kingston Ontario Canada

- 2Queen’s University, Faculty of Health Sciences, Kingston Ontario Canada

Corresponding Author

Gavin C.A Wood, Kingston General Hospital, Department of Surgery,76 Stuart Street, Kingston Ontario Canada, K7L 2V7, Tel: 4899(613)549-6666, E-mail: woodg@KGH.KARI.NET

Citation

Wood, G.C.A., et al. Exploring Patients’ Perceptions of Their Surgeon Based on Attire. (2016) J Anesth Surg 3(2): 208- 212.

Copy rights

© 2016 Wood G.C.A. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Abstract

Background: Physician attire is an important factor in the patient’s first impression of their doctor. The purpose of this study is to determine how different forms of attire impact patient perceptions of their physicians within our orthopaedic clinics.

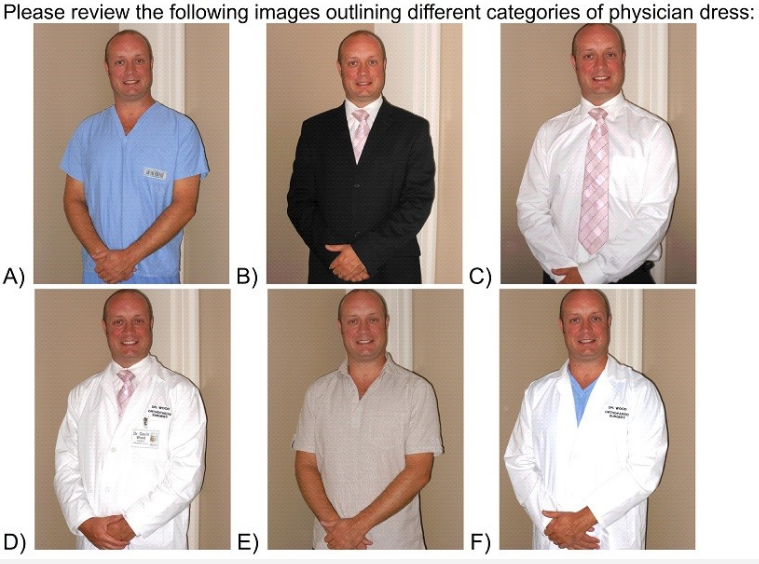

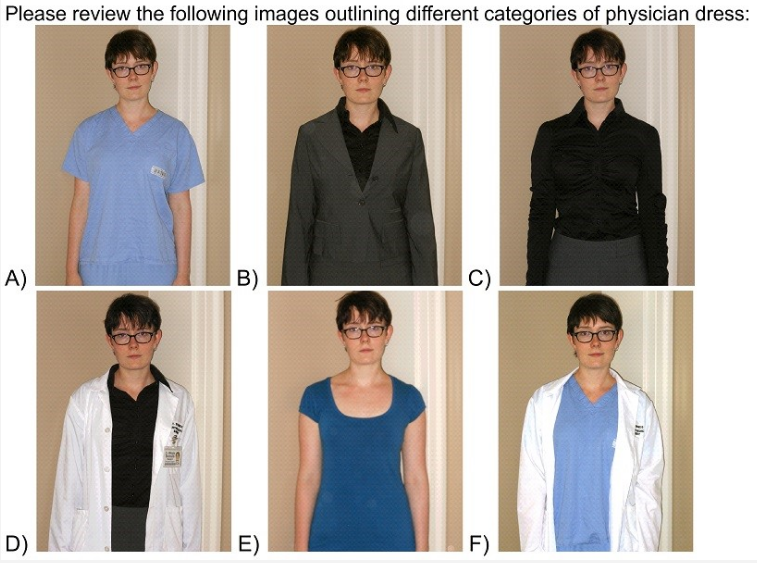

Methods: A survey was distributed to new patients visiting an orthopedic surgery clinic within a 9 month span at a Canadian outpatient hospital. Each participant also received either a male or female photo sheet depicting 6 different forms of physician attire: Surgical scrubs and white coat, surgical scrubs alone, formal wear with white coat, formal wear alone, business suit and casual wear. Demographic data and general questions related to surgeon’s attire as well as specific questions pertaining to the pictures provided were collected.

Results: 100 patients responded to the survey. Most respondents agreed that physician attire was important and they expected their surgeon to be dressed professionally. Respondents felt strongly that there was an association between how a physician dressed and their perceived ability to dispense care. There was a significant preference for the surgeons wearing a white coat. The least favored surgeon attire overall was casual wear.

Discussion: The results from our survey identify the importance of surgeon’s attire in the patient’s perception of their surgeon as a health care provider. Attire was identified as influencing patient confidence and possible likelihood of compliance/follow-up.

Conclusion: We have identified the white coat as being an important adjunct to the surgeon’s attire that embodies professionalism and inspires confidence in a surgeon.

Introduction

Background

Surgeons and residents at Queen’s University affiliated hospitals wear a wide range of attire when performing clinical duties. With the absence of a dress code policy, health care practitioners have been observed wearing anything from shorts and sneakers to full business suit attire. The long white lab coat, a distinctive article which was once a staple in modern physician attire, has gradually been phased out, unpopular amongst newer medical graduates. A recent study in the UK demonstrated infection risk and heat factors to be the most commonly quoted reasons why more and more doctors have chosen to abandon the white coat[1].

Among health care providers, the topic of physician attire has long been discussed as an important factor in the patient’s first impression of their doctor. As far back as the era of Hippocrates, certain benchmarks were set by the profession and physicians were advised to “be clean in person, well-dressed, and anointed with sweet smelling unguents”[2]. However, results of contemporary medical literature on the patient’s perspective of physician attire and how it relates to their level of confidence and satisfaction towards the care they receive appear to be mixed. Whereas some studies strongly support the use of white coats[3-5] others fail to demonstrate the value of a strict dress code[6]. It is likely that geographical and socioeconomic factors in populations along with cultural norms play a role in shaping this perspective. The purpose of our study was to determine how different forms of attire impact patient perceptions of their orthopedic doctor at our institution.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a survey-based cross-sectional study over a 9 month period, recruiting new orthopedic patients at their first-time visit to an outpatient faculty-run orthopedic clinic. After consent was obtained, the enrolled participants received a copy of our study questionnaire which consisted of 3 sections. The first section required the participant to answer a number of demographic questions. The second section consisted of 6 general questions related to physician attire and included the following:

1) When I am referred to a physician’s clinic for a consultation, I expect him/her to be dressed in a professional manner.

2) The way a physician dresses when I come to him/her for a consultation is important to me.

3) The way a physician dresses affects my confidence in their ability to dispense care.

4) When I visit a physician that is dressed unprofessionally, I am more likely to dismiss their recommendations.

5) When I visit a physician that is dressed unprofessionally, I am more likely to seek out a second opinion.

6) The current styles of dress used in hospital clinics clearly identify the different caregiver roles (ie. Nurse, physiotherapist, ward clerk, orderly, physician).

For the third section participants’ were asked to answer 17 questions pertaining to a series of photos. These randomly selected laminated photo sheets depicted either a male or female physician wearing 6 different types of attire: 1) surgical scrubs and white coat, 2) surgical scrubs alone, 3) formal wear with white coat, 4) formal wear alone, 5) business suit and 6) casual wear (Figures 1 and Figure 2). The surgeon’s stance and facial expression remained constant, with attire as the only variable. The types of attire were labeled in random order A) through F) and descriptive titles omitted to prevent bias. Responses were on a 5 point scale ranging from strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree to strongly disagree.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic variables. Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare answers between age (above and below 55), sex and education levels (elementary, secondary, post secondary). An alpha value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS 21.0. Ethics approval was approved by the Queen’s University Human Ethics Board.

Results

A total of 126 study surveys were distributed to eligible participants at the time of clinic registration. One hundred and sixteen patients signed the consent form and participated in the study. Sixteen surveys were discarded due to lack of demographic information, leaving 100 surveys for analysis. If there were incomplete section in the 2nd or 3rd section of the survey, they were included in the analysis.

Forty one male and 59 female adult participants responded to the survey. The average age was 55 years. Complete demographic data are listed in (Table 1). Fifty one participants answered the third section of the questionnaire viewing the photos depicting a male physician, while the remaining 49 participants examined the photos depicting a female physician.

Table 1: Demographic data.

| Mean age | 55.11 |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| M | 41 |

| F | 59 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 93 |

| Native | 2 |

| Other | 4 |

| N/A | 0 |

| Country of origin | |

| Canada | 80 |

| USA | 7 |

| Other | 13 |

| Province of origin | |

| Ontario | 61 |

| Quebec | 6 |

| Other | 12 |

| Primary Language | |

| English | 96 |

| French | 3 |

| Other | 1 |

| Education | |

| Home School | 0 |

| Elementary | 3 |

| Secondary | 29 |

| Post-secondary | 68 |

| Employment | |

| Student | 2 |

| Part-time | 6 |

| Full-time | 40 |

| Retired | 37 |

| Unemployed | 6 |

| Disability | 9 |

| Dress code at place of employment | |

| Yes | 30 |

| No | 65 |

In the second section that addressed 6 general questions, significantly more patients overall agreed that physician attire is important to them and they expect their surgeon to be dressed professionally (p = .003). Also, people felt strongly that there was a connection between how a physician dresses and their ability to dispense care (p = .001). However, participants disagreed that they would dismiss a surgeon’s recommendations or seek out a second opinion based on attire that they felt was “unprofessional” (p = .05). Interestingly, there was no significant agreement or disagreement on whether current styles of dress in hospitals and clinic helped to identify the different caregiver roles. There were no significant differences on any of the general question responses. No significant differences on any responses to these 6 questions were found when stratified by gender, age (above 55, below 55) or education level.

When examining participant responses to the physician attire photos, respondents showed the same preferences when shown the photos of the female and male physician. There were exceptions for the 3 questions: If your family physician gave you the option to see either of these doctors for a surgical opinion, which would you choose? Which doctor would you be most likely to follow advice regarding non-surgical options (physiotherapy, medications, exercises, lifestyle modification, casts/ splints)? And which doctor would you be most likely to return to for follow-up? For all 3 questions, significantly more respondents chose the physician wearing a white coat with scrubs when viewing the male photo, while significantly more participants chose the formal attire with white coat when viewing the female photo.

We were also interested in examining responses to the female and male photos separately based on the respondents’ sex, age and education levels. For those who responded to the female physician photos, there were no significant differences in responses when stratified by sex or education level, but there were a few significant differences between those aged 55 and above, and those aged below 55 (Table 2). In contrast, there were some significant differences for those who responded to the male physician photos on sex and age, but not on education level (Table 3).

Table 2: Female Physician Photos: Significant Differences Stratified by Age.

| Question | Below age 55 | Above Age 55 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| If your family physician gave you the option to see either of these doctors for a surgical opinion, which would you choose? | Surgical scrubs with white coat | Formal wear and white coat | .01 |

| Which doctor would you least prefer to have operate on you? | Casual wear (75%) | Casual wear (38%) | .04* |

*younger respondents twice as likely to choose this response

Table 3: Male Physician Photos: Significant Differences by Age and Sex.

| Question | Below age 55 | Above Age 55 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Which doctor would you expect to be the most caring? | No clear preference | Surgical scrubs with white coat | .02 |

| Question | Male | Female | P value |

| Which doctor would you be least likely to follow advice regarding non-surgical options (physiotherapy, medications, exercises, lifestyle modification, casts/splints)? | Business suit | Casual wear | .01 |

| Which doctor would you least prefer to have operate on you? | Business suit | Casual wear | .01 |

| Which doctor would you be least likely to return to for follow-up? | Business suit | Casual wear | .01 |

| Which doctor would you expect to be the least caring? | Business suit | Casual wear | .03 |

| Which doctor would you be the least likely to return to in the event of an unsuccessful surgery? | Business suit | Casual wear | .03 |

Discussion

The results of our study clearly demonstrate the impact of physician attire on patients’ first impression of their surgeon as well as on their level of confidence. The white coat (combined with formal wear or scrubs), was the preferred attire in all circumstances. Many previous studies across specialties and across the world have shown a preference among patients for doctors who wear white coats[1,3-5,7-10]. While some patients prefer the white coat for its ability to inspire confidence and ease communication[7,11] others feel it is an important means of identification distinct from the name tag[1]. Patients in our study cohort felt the surgeon’s wearing white coats appeared more experienced and caring overall, a finding which has been shown in previous studies[10-12]. ‘Patients also chose the white coat wearing surgeons as the ones they would be most comfortable with discussing personal issues, following advice and returning to in the event of a complication’. A recently published study from the US found the white coat inspired trust, confidence, intelligence and safety[5]. Similar findings were also reported in a previous study which surveyed internal medicine outpatients[11].

Our study has demonstrated clear expectations from our surgical patients regarding physician attire. However, it is less clear whether failure to meet these expectations would negatively influence the perception of the care provided. In a recent study examining surgeon’s attire specifically, Major et al. found overwhelming agreement amongst patients that a surgeon’s appearance influences opinions related to medical care. Surgical inpatients as well as the non-hospitalized population in this study showed a strong bias that all surgeons should wear white coats and nametags while seeing patients. A more recent study performed by Edwards et al., found only 37% of the surgical outpatients believed surgeon’s attire influenced the opinion of the care they received. However, over half this sample felt surgeons should wear white coats while seeing patients[6].

Another important aspect of evaluating surgeon’s attire is exploring the scrubs option. In many new television shows and movies, scrub attire is becoming ubiquitous in the simulated hospital setting. In our institution, many consultants frequently travel back and forth from the operating suite to the outpatient clinic to visit patients while wearing scrubs. In the only two other studies specifically geared towards surgical patients, the opinion of scrubs has been variable. Whereas polled surgeons believe scrubs to be appropriate attire while seeing patients, this belief has been inconsistent among patients[4,6]. We believe our study provided a suitable answer to the scrubs issue. When a white coat was added to scrubs, this effectively boosted patient preference, with a trend towards preference over formal clinic wear.

Although the white coat is clearly popular amongst patients, certain physicians choose not to wear it for the potential infection risk or due to heat factors[1]. In the UK, hospital personnel abide by a “bare below the elbows” policy due to concerns of the potential transmission of nosocomial infections from infrequently laundered long-sleeved white coats. However, this policy has sparked controversy given the limited data supporting its implementation.

Although experimental studies have identified the presence of potentially pathogenic bacteria while swabbing white coats[15,16] no clinical study exists to correlate this finding with rates of nosocomial infections. In fact, a recent randomized study in 2011 found no difference in bacterial contamination between newly-laundered short sleeve garments at 8 hours of wear compared to physician white coats or skin at the wrist[17]. Another study involving swabs of physician apparel and accessories determined that pens, stethoscopes and cell phones were much more likely to exhibit bacterial contamination compared to white coats[18].

One limitation of this study includes the nature of the data collection. Although surveys can be an effective way to obtain valuable patient-reported data, they can be subject to reporting bias. Although our response rate for the questionnaire was very high (92%), we could not account for the data from non-responders, which may have skewed our results. Our survey, although similar to those used in other studies cited in this article, is not validated and therefore may also introduce bias. Our study was designed to specifically address the initial patient perceptions of a surgeon based on attire. As such, our survey was distributed only to new patient referrals patients prior to their initial consultation with a surgeon. Since only orthopedic surgery outpatients were studied, our findings may not be generalizable to other surgical specialties. Also, our questionnaire did not specify the setting in which each type of attire was worn, which may have introduced bias. A recent UK study by Gherardi et al. demonstrated that patient’s opinions regarding different forms of attire were somewhat influenced by the setting, with scrubs being more desirable in the emergency department compared to the outpatient setting[3]. Our patient sample is from a single center, where the population is relatively homogeneous and predominantly Caucasian. Therefore, findings may not be applicable to centers which serve a more ethnically diverse population.

Conclusion

The results from our study identify the continuing importance of surgeon’s attire in the patient’s perception of their surgeon as a health care provider. Attire was identified as an independent factor affecting patient confidence and possibly likelihood of compliance and follow-up. We have identified the white coat as being an important adjunct to the surgeon’s attire that embodies professionalism and inspires confidence in a surgeon. These findings echo the results of several studies across the world and in specialties ranging from family practice to internists and surgeons[1,3-5,7-10]. Therefore, if a surgeon wishes to “dress to impress”, we recommend investing in a clean white coat, even if only to be worn over scrubs.

References

- 1. Douse, J., Derrett-Smith, E., Dheda, K., et al. Should doctors wear white coats? (2004) Postgrad Med J 80(943): 284–286.

- 2. Brandt, L.J. On the value of an old dress code in the new millennium. (2003) Arch Intern Med 163(11): 1277– 1281.

- 3. Gherardi, G., Cameron, J., West, A., et al. Are we dressed to impress? A descriptive survey assessing patients’ preference of doctors’ attire in the hospital setting. (2009) Clin Med 9(6): 519–524.

- 4. Major, K., Hayase, Y., Balderrama, D., et al. Attitudes regarding surgeons’ attire. (2005) The American Journal of Surgery 190(1): 103–106.

- 5. Jennings, J., Ciaravino, S.G., Ramsey, F.V., et al. Physicians’ Attire Influences Patients’ Perceptions in the Urban Outpatient Orthopaedic Surgery Setting. (2016) Clin Orthop Relat Res 474(9): 1908-1918.

- 6. Edwards, R., Saladyga, A., Schriver, J.P., et al. Patient attitudes to surgeons’ attire in an outpatient clinic setting: substance over style. (2012) Am J Surg 204(5): 663–665.

- 7. Gooden, B.R., Smith, M.S., Tattersall, J.N., et al. Hospitalized patients’ views on doctors and white coats. (2001) Med J Aust 175(4): 219–221.

- 8. Ikusaka, M., Kamegai, M., Sunaga, T., et al. Patients' attitude toward consultations by a physician without a white coat in Japan. (1999) Intern Med 38(7): 533-536.

- 9. Menahem, S., Shvartzman, P. Is our appearance important to our patients? (1998) Fam Pract 15(5): 391-397.

- 10. Au, S., Khandwala, F., Stelfox, H.T. Physician Attire in the Intensive Care Unit and Patient Family Perceptions of Physician Professional Characteristics. (2013) JAMA Intern Med 173(6): 465-467.

- 11. Rehman, S.U., Nietert, P.J., Cope, D.W., et al. What to wear today? effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. (2005) Am J Med 18(11): 1279-1286.

- 12. Chung, H., Lee, H., Chang, D., et al. Doctor’s attire influences perceived empathy in the patient-doctor relationship. (2012) Patient Education and Counseling 89(3): 387–391.

- 13. Kerr, C. Ditch that white coat. (2008) CMAJ 178(9): 1127.

- 14. Henderson, J. The Endangered White Coat. (2010) Clin Infect Dis 50(7): 1071–1073.

- 15. Loh, W., Ng, V., Holden, J. Bacterial flora on the white coats of medical students. (2000) J Hosp Infect 45(1): 65–68.

- 16. Treakle, A., Thom, K., Furuno, J., et al. Bacterial contamination of health care workers white coats. (2009) Am J Infect Control 37(2): 101-105.

- 17. Burden, M., Cervantes, L., Weed, D., et al. Newly Cleaned Physician Uniforms and Infrequently Washed White Coats Have Similar Rates of Bacterial Contamination After an 8-Hour Workday: A Randomized Controlled Trial. (2011) J Hosp Med 6(4): 177–182.

- 18. Pandey, A., Asthana, A., Tiwari, R., et al. Physician accessories: Doctor, what you carry is every patient’s worry? (2010) Ind J Path Micro 53(4): 711-713.