Farmers’ Perception of the Impacts of Climate Variability and Change on Food Security in Rubanda District, South Western Uganda

Byamukama W*, Bello N.J and Omoniyi T.E

Affiliation

Department of Agricultural and Environmental Engineering, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Corresponding Author

Byamukama Willbroad, Department of Agricultural and Environmental Engineering, University of Ibadan, Nigeria; E-mail: willbroad2016@gmail.com; bwillbroad@kab.ac.ug

Citation

Willbroad, B., et al. Farmers’ Perception of the Impacts of Climate Variability and Change on Food Security in Rubanda District, South Western Uganda. (2018) J Environ Health Sci 4(2): 64- 73.

Copy rights

© 2018 Willbroad, B. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Climate Variability and Change; Food security; Rubanda district; Agricultural production; Farmers’ perception

Abstract

Climate variability adversely impacts crop production and imposes a major constraint on farming planning, mostly under rain fed conditions across developing countries. Considering the recent advances in climate science, many studies are trying to provide a reliable basis for climate, and subsequently agricultural production forecasts. Rainfall and temperature variability from season to season greatly affects soil water availability to crops, and thus poses crop production risks to agriculture which is a major economic activity in Rubanda District, Southwestern Uganda. It was observed that farmers tend to rely on their accumulated experience about weather conditions in the schedule of their farm operations. Therefore this study was designed to examine farmers’ perception of the impacts of climate variability and change on food security in Rubanda District of Southwestern Uganda.

Primary data were obtained through questionnaire administration and field observations among the farmers in Rubanda district. Secondary data was obtained from Kabale Meteorological center (rainfall and temperature) between 1976 and 2016. Simple random sampling technique was employed in the selection of sample size and a total of 200 farmers were randomly selected for the study. The selection of the sample size was based on the procedure of Yamane (1967). Microsoft Excel office 2013 was used to show trends of climate variability and change and SPSS version 20 for descriptive analysis.

The results of the analyses showed that temperature increased significantly whereas a decreasing trend of rainfall was observed. Farmers perceived the variability of the climate to have led to the decline of agricultural production hence impacting on food security. The chi-square analysis showed that Climate variability and change has significant relationship with food availability (p < 0.05), food access (p < 0.05), food consumption (p < 0.05) and food stability (p < 0.05). The test also showed that there is variation in the perception of climate variability and change among the farmers in Rubanda District (p < 0.05).

Climate variability and change factors have the potential for climatic stress on food security according to the observed agricultural production decline and farmers are seasonally faced with problems of food deficits due to unpredicted extreme weather events.

The study established that policies, improved access to climate forecasting and dissemination and accessible extension service should be directed toward interventions to improve agriculture productivity by addressing issues concerning aspects of climate variability and change that constantly affect the dimensions of food security.

Introduction

Background to the study

Climate change is one of the most serious threats to sustainable development in Uganda, with adverse impacts on the environment, human health, food security, economic activities, natural resources and physical infrastructure (FAO, 2007; Asiimwe & Mpuga 2007). Global climate varies naturally, but scientists agree that rising concentrations of anthropogenic produced greenhouse gases in the earth’s atmosphere are leading to changes in the climate. The World Economic Forum outlined the five core areas of global risk as economic, environmental, geopolitical, societal and technological. Within these, climate change is understood as one of the unimportant challenges for the twenty-first century, as it is a universal risk with impacts far away from the environment.

Tropical countries such as Uganda are particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts, mostly changes in rainfall, because of their exposure to extreme weather events and dependence on natural resources. Due to persistently occurring drought, high temperatures, storms, hurricanes and flooding, food insecurity is of global alarm specifically in less developed countries. The situations are highly serious in Sub-Saharan Africa. In most African countries including Uganda, farming depends almost entirely on quality of the rainy period. This makes Africa mainly susceptible to climate variability/change. Climate projections in apathetic emission scenarios denote that Uganda will be warmer with an addition in minimum temperature of between 1.0 and 1.5°C by 2030 with regard to the year 2000 as baseline year. Maximum temperatures are predicted to increase in some areas of the country by 3°C and decrease in other areas of the same scale. By 2050 minimum temperatures in Uganda are anticipated to increase by 2°C (Adger, 2006).

Climate change, however, has pose the greatest threat to agriculture and food security in the 21st Century, mostly in many agriculture-based countries of Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) especially Uganda with their low ability to cope (Jan et al., 2008; Goulden et al., 2009; IPCC, 2001; Tandon, 2009; FAO, 2008). Present climate variability and change i.e. extreme weather events such as drought and floods previously lead to major economic cost in Uganda’s agricultural sector.

Uganda’s population growth rate is about 3.5 percent, while the annual growth rate of food production is about 1.5 percent. These statistics clearly indicate that the current food production levels cannot keep pace with the population growth and that the country is likely to experience acute food shortage in the near future (Hisali et al., 2011). The agricultural sector, which is dominated by small scale, mixed crop and livestock farming, is the mainstay of the country’s economy. Agriculture is the major sector contributing about 25% to the country’s GDP and offering direct employment to over 70% of Uganda’ population and account for nearly 50% of the total export earnings (UBOS, 2016). Its dependence on agriculture makes the country particularly vulnerable to the adverse impacts of climate change on crop and livestock productions (UBOS, 2017).

Climate variability and change influences all the dimensions of food security: food availability, food accessibility, food utilization and food systems stability in Uganda (Connolly-Boutin, 2016). Coping with climatic variability is certainly not new for Ugandan farmers, but the problem is that existing coping mechanisms may not match with the level of prevailing challenges that are likely to be faced in the future (Bashaasha et al., 2010).

In Rubanda District, climate change has direct negative effects on agricultural production and on the national economy too, with increases in food prices leading to an unstable macro economy and discouraging foreign investment (Birungi & Hassan, 2010). Frequent health problems (disease out breaks due to climatic changes and gastro intestinal infections) affect food production and incomes, which also leads to decreased standards of living.

Agriculture is a major source of livelihood for many in Rubanda District. It is practiced mainly for food. Thus, there is a symbiotic relationship of paramount importance between agriculture and communities livelihoods. However much contribution of climate change in the district has led to low agricultural productivity, majority of the farmers in Rubanda district are still practicing subsistence rain fed agriculture which has been affected by the changing climatic trends (MFPED, 2005). Climate change and variability has had adverse impacts on environment, human health, food security, economic activity, resources and physical infrastructures of Rubanda District (Zizinga, 2013). Although other sectors of the district like social, economic and political also face the impact of climate change at varying degrees, the worst hit sector is the rain fed agriculture due to its high sensitivity to climate stimuli. As a result of the impact on this particular sector (agriculture), food production systems, food security status of households and domestic industries have been disrupted.

Climate related disasters like droughts and floods are becoming the key factors affecting Rubanda’s agriculture which is the main livelihood source for households (Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development, 2012). Hence, this study aims at investigating farmers’ perception of the impacts of Climate Variability and Change on food security in Rubanda district, south western Uganda and identifies coping strategies and build on adaptive capacity of households in Rubanda District.

Research Question

What is the trend of climate variability from temperature and rainfall records from 1976 to 2016 in Rubanda District?

Research Hypotheses

(i) H0: Climate variability and change in Rubanda District has no relationship with food security in the area.

(ii) H1: There is variation in the perception of the impacts of climate variability and change on food security among the farmers in Rubanda District.

Justification for the Study

The present inability to meet the food demand of Ugandans and the challenge posed by climate change and variability emphasized the need for the improvement of food crop farmers (Birungi & Hassan, 2010). Failure to know the present food crop production efficiency and the influence of climate change coping strategies on efficiency level of food crop production inhibited designing and formulating appropriate policies to meet food crop production demands of the country (FAO, 2008). Developing economies can benefit much from efficient studies especially a type like this that incorporates farmers’ perception and adaptation strategies to climate variability and change to explain productivities.

Scope of the study

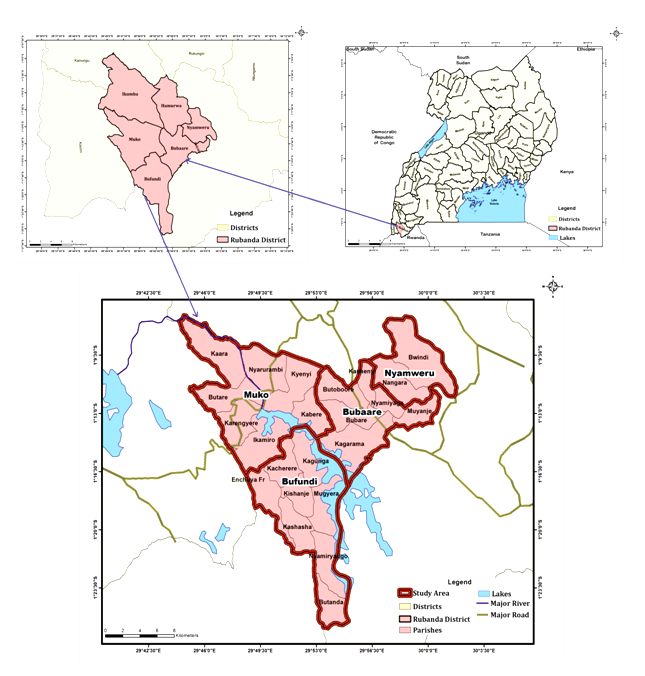

Rubanda District is bordered by Kabale District to the east and north, Kanungu District to the north-west, Kisoro District to the west, and Rwanda to the south. The town of Rubanda is approximately 35 Kilometers (22 mi), by road, west of Kabale, the largest city in the Kigezi sub-region. It was established by an Act of Parliament on 3 September 2015 and became operational on 1 July 2016. Before its creation, the district was Rubanda County in neighboring Kabale District. The rationale for its creation was to “bring services closer to the people” and to improve “service delivery” to constituents. The district has an elevated altitude, with volcanic mountains and hills, separated by V-shaped valleys. The 2014 national housing and population census estimated the population of the District at 201,600. Majority of the population depend on agriculture to meet their food and income needs. Both crops and livestock are produced at subsistence level with major food crops like, maize, matooke (banana), millet, beans, sweet potatoes, irish potatoes, sorghum and passion fruits as well as cash crops like tea.

More so, the study is based on the farmers’ perception of the impacts of Climate Variability and Change on food Security in Rubanda District, South Western Uganda. It focused primarily on examining the status of the socio-economic characteristics of farmers in in Rubanda District, establishing graphically the evidence of climate variability and change from temperature and rainfall records between 1976 and 2016 in Rubanda District, establishing farmers’ assessment of the impacts of climate variability and change on climatological hazards (floods, drought, landslides etc.) in Rubanda District, assessment of farmers’ perception of the impacts of climate variability and change in Rubanda District and examining strategies adopted by farmers in response to the impacts of climate variability and change in Rubanda district.

Review of Literature

Climate Variability in Uganda

Rubanda District experiences a diversity of climatic conditions. Annual rainfall ranged between 600 mm and 1600 mm, mostly distributed in low land and in the highlands zone. Most rainfall (rainy season) occur in January, February, March, April, November and December. The pattern of rainfall is bimodal with the rainy season lasting from August–December and February-May followed by a prolonged dry season. Precipitation is reliable and allows a wide range of crops to be grown with some double planting of short season crops.

Lowland areas are warm for most part of the year. Mean daily temperature ranges between 230c in February, 25ºC in December and January to 28ºC in September. Temperature varies inversely with altitude. Lowland zone tends to be warmer than the highlands zone.

Climate variability is increasingly emerging as one of the most serious global problems affecting many sectors in the world and is considered to be one of the most serious threats to sustainable development with adverse impact on environment, food security, human health, economic activities, natural resources and physical infrastructure (Majaliwa et al., 2009; IPCC, 2001) Based on many studies covering a wide range of regions and crops, negative impacts of climate change on crop yields have been more common than positive impacts (Maddison, 2006). Africa is identified as one of the most vulnerable regions to climate variability in the world where Uganda is inclusive and ninety eight percent of the agricultural activities in Uganda are rain-fed (UNEP, 2009; MFPED, 2005). As the backbone of Uganda’s economy, agriculture is very vulnerable to increasing temperatures, droughts and floods, which reduce crop productivity.

Droughts and floods are not new phenomena in Uganda. Their characteristics, intensity, duration and spatial extent vary from one event to the other (Nabikolo et al., 2012). The frequency of occurrence and severity of floods and droughts have been increasing over time. For instance, the frequency of drought increased from once in every 10 years in 1970s, to once in every 5 years in 1980s, once in every 2 - 3 years in 1990s and yearly since 2000 (Molua, 2008). The alternating cycles of droughts and floods do not only destroy the livelihood sources but also severely undermine the resilience of the people living in the affected areas (World Bank, 2008). In some arid and semi-arid counties, pastoralists have lost more than half of their livestock to droughts in the past ten years with over 60% of the inhabitants living below the poverty line (Seo & Mendelsohn, 2008). Today, famine relief due to climate extremes is a regular feature in some parts of the arid and semi-arid districts such as Kabale.

Climate variability is also noticeable in the country whereby increase in the frequency of prolonged droughts, increase in the cases of landslides during flood events, changes in river regimes including river courses (Nzeadibe, et al., 2011; NAPA, 2007). The action plan report also noted reduction of water levels in rivers.

Scientific findings show a growing consensus that the world has to grapple with increasingly severe climatic events. Some of the manifestations of climate change are rising average temperatures with the last three decades having got successively warmer (Molua, 2008; Lobell, et al., 2008), increasing sea levels which have been rising at an average 1.8 mm/year between 1961 and 1992 and about 3.1 mm/year since 1993 (IPCC, 2001; Kabubo-Mariara & Karanja, 2006) and the thinning snow cover in the Northern Hemisphere. In Uganda, studies indicate that temperatures have generally risen throughout the country, primarily near the large water bodies (Kimmerer, 2002). Other projections also indicate increases in mean annual temperature of 1 to 3.5ºC by the 2050s (IPCC, 2001). This has the potential to inundate agricultural lands and cause food insecurity.

Generally, Uganda’s climate is also expected to warm across all seasons during this century. Under a medium emission scenario, the annual mean surface air temperatures are expected to increase between 3°C and 4°C by 2099, which means it was rise at a rate of 1.5 that of the global average (Goulden, M., 2008). The country’s arid and semi-arid lands (ASALs) have already witnessed a reduction in extreme cold temperature occurrences (FAO, 2007). This warming has led to the depletion of glaciers on Mountains like Ruwenzori (IPCC, 2007; UNEP, 2009). In addition, the rising temperature levels was inevitably lead to higher rates of evapotranspiration, further reducing the impact of rainfall on soil water for crop growth (Enete & Onyekuru, 2011). As predicted by Deressa et al., (2010) these temperature increases are also expected to lead to overall increase in annual rainfall of around 7% over the same period, although this change was experienced uniformly across the region or throughout the year (Berkes & Jolly, 2001). Seasonal rainfall trends are already mentioned to be mixed, with some locations indicating increasing trends while others showing decreases. Moreover, the expected increase in the variability of rainfall and the increase in temperatures are likely to increase the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events in the region, meaning that many areas in East Africa was faced with an increased risk of longer dry spells and heavier storms with a direct effect to food security (Benin et al., 2008).

It is therefore worth mentioning that climatic seasonality and unpredictability causes fluctuations in crop production and contributes to food insecurity. This calls for predictability and vulnerability studies on climate variations to reduce on food fluctuations probabilities especially in Western and other parts through outlining the current and past weather occurrences of the area as per the years specified for early warning purposes (Ainsworth & Ort, 2010).

The Effects of Climate on Crop Yields in Uganda

In Uganda, agriculture contributes about 20% to the GDP, 48% to export earnings, and employs about 73% of the population. In addition, more than 4 million Ugandan households depend on small-scale farming for their sustenance. Thus, poverty reduction in Ugandan is tied to improvements in the agricultural sector.

Warmer conditions recently in Uganda have reduced yields of crops and pastures by preventing pollination. For example, rice yields decrease by 10% for every 10C increase in minimum temperature during the growing season (Kassahun, 2009). Increases in temperature, at the same time, has affected the lower altitude areas where temperatures are already high. Higher temperatures affect both the physical and chemical properties in the soil. The increased temperatures have accelerated the rate of releasing CO2 resulting in less than optimal conditions of net growth. When temperatures exceed the optimal level for biological processes, crops often respond negatively with a steep drop in net growth and yield. The heat stress affects the whole yield of cultivated crops in Uganda because Agricultural systems in Uganda are highly sensitive to both land use and climatic conditions. (Hisali, 2011).

More also, there have been an observable increased pests and diseases: Higher temperatures and longer growing seasons has led to the encouragement of damaging pest populations (Enete, 2011). In his opinion Deressa (2010) posited that higher temperatures provide a conducive environment for the majority of insect pests. He further observed that longer growing seasons, higher night temperatures, and warmer winters help insect pests undergo multiple life-cycles and has led to decreased in plant production in Uganda.

Farmers’ Perceptions of Climate Variability on Food Security in Uganda

One’s perception depends on one’s environment and its characteristics (Asiimwe & Mpuga 2007). It is in this notion that Below et al., (2010) believes that most farmers’ knowledge and exposure to climate change has been influenced indirectly by the media from events occurring in distant areas, e.g., the melting of ice sheets in the Antarctica rather than local events. Birungi, & Hassan, (2010) also indicated that experience is an important factor that shapes individuals’ perceptions, in terms of seasonality, with previous experiences of poor seasons bringing in memories and being responsible for how farmers may tend to describe different season types and be able to relate with food security. Perception has been described as referring to a range of judgments and attitudes (Cline, 2007). Deressa (2008) suggests that the farmers’ perceptions on climate change and variability are important in adaptation as they determine decisions in agricultural planning and management by the farmers. As well, documenting how farmers’ frame the conditions they experience are crucial for understanding their responses to said conditions (Ford 2006; Hassan & Nhemachena 2008) especially for different land potential capacities.

In the climate variability literature, traditional ecological knowledge (Jan et al., 2008; Kassahun, 2009), local knowledge and local ecological knowledge (Olsson et al., 2004) are used to refer to the cumulative body of knowledge, practice and belief, that are location- specific, acquired through long-term observation of (and interaction with) the environment, and transferred through oral traditions from generation to generation. Based on the available literature, this current study used local knowledge to mean a cumulative body of knowledge on weather and climate variability and its’ effect on food security in the area (Kassahun, 2009).

The validity of local knowledge has been shown by scientists through comparison with quantitative climate data analysis (Cabrera et al., 2006). The majority of studies show that farmers’ resourcefulness matches quantitative data analysis: local knowledge is used to respond to the vagaries of climate such as droughts, famines, floods and other stresses that threaten crops and livestock (Kimmerer, 2002). However, there have also been cases where local knowledge failed to match quantitative climate data, making local knowledge seem unreliable, e.g., as reported from Kenya by Molua (2008). This study was built on other authors who have cross-checked local knowledge with quantitative climate data to ascertain its relevance for climate variability. The study also provided evidence of farmers’ perceptions matching with the existing quantitative historical climate data of Kenya for the past 30 years (1980 - 2012).

Sea-level rise and saltwater intrusion: Rising sea waters reduced viable crop areas in the deltas and along coasts. Further rises in sea-level was required adaptation measures to protect crops. In the longer term, if the current situation is maintained, sea-level rise could have catastrophic impacts on deltas and coastal areas (Adger, 2006). The current global estimate of sea level rise is 0.2 m and it is projected to increase to 1m by the year 2100 (Adebayo et al., 2011). Coastal settlements in Nigeria like Bonny, Forcados, Lagos, Port Harcourt, Warri and Calabar among others that are less than 10 m above the sea level would be seriously threatened by a meter rise of sea-level (ACCCA, 2010).

Strategies in Response to Climate Variability and food security in Uganda

The two major types of adaptation are autonomous and planned adaptation (FAO, 2007). Autonomous adaptation has been defined as the “ongoing implementation of existing knowledge and technology in response to the changes in climate experienced (IPCC, 2001). It is often conceived by individuals or small groups’ reactions to varying conditions (Reilly and Birungi, & Hassan, 2010). Many autonomous adaptation options are extensions or intensifications of obtainable risk management or production-improvement activities for cropping systems, livestock, forestry and fisheries production (Cline, 2007).

Planned adaptation, on the other hand, is the term to include more harmonized action on higher aggregation levels, or “the increase in adaptive capacity by mobilizing institutions and policies to set up or strengthen conditions positive for effective adaptation and investment in new technologies and infrastructure (Below et al., 2010).

Policy based adaptations to climate change were interrelated with, depend on, or perhaps even be just a compartment of policies on natural resource management, human and animal health, governance and human rights, among a lot of others (Berkes & Jolly 2001). IPCC (2001) defined climate change adaptation as ‘alteration in nature or human system in response to actual or predictable climatic incentive or either effect, which demonstrates harm or exploits valuable opportunities’. The Inter Agency Report (2007) also defines climate change as the capacity to respond and adjust to actual or potential impacts of changing climate conditions in ways that modest harm or take improvement of any positive opportunity that the climate could afford. Mitigating climate change means reducing greenhouse gas emissions and sequestering or storing carbon in short term together with development choices that lead to low emissions in the long-term. Acclimatization is essentially adaptation that occurs spontaneously through self-directed efforts. It is influential and effective adaptation strategy. In simple terms, it means getting used to climate change and learning to live with it. Adaptation to climate change involves purposeful adjustments in natural or human systems and behaviors to lessen risks to people’s lives as well as livelihoods. All living organisms, including humans, adapt and develop in response to changes in climate and habitat (FAO, 2008). The need for adaptation may be augmented by growing populations in areas vulnerable to extreme events. However, adaptation only is not expected to cope with all the projected effects of climate change with no mitigation especially not over the long term because most impacts increase in scope as level of environmental deterioration is increasing due to higher level of growing population.

Adaptations may vary not merely with respect to their climatic stimuli but also with respect to other, non-climate conditions. They are sometimes called intervening conditions, which serve to manipulate the sensitivity of systems and nature of communities’ adjustments. For instance, a series of droughts may have like impacts on crop yields in two areas, but differing economic and institutional arrangements in the two areas could well result in entirely dissimilar impacts on farmers and hence in completely different adaptive responses, both in the short and long terms Benin et al., (2008).

Communities in many parts of the world have often tried to use a range of coping mechanisms as a way of responding to an experienced impact with a short term vision in order to reduce the effects of the variations and changes in climate on yield reduction (Berkes & Jolly 2001). Traditional coping methods are often based on experience accumulated over the years and transmitted from generation to generation (Adger 2006). Coping mechanisms in reaction to the stress caused by climate variability and change are obtained from a number of studies (Awotoye & Mathew 2010). These studies indicated the following coping mechanisms; collection of wild foods, purchasing food from the market, in-kind (food) payment, Support from relatives and friends, sales from livestock and household valuables, migration and wage labor in exchange for food, reduction in the number of meals served each day, reduction in the portions/sizes of meals and consumption of less preferred foods. Farmers have also managed to cope up by water rationing during periods of drought, rain water harvesting, re-use of water for example water from washing clothes or utensils to irrigate crops in the backyard gardens and nurseries, carry out mixed cropping, adjustment in land and crop management (Adger, 2006; Berkes & Jolly 2001). Furthermore, communities have also employed coping mechanisms such as reliance on social networks i.e. sharing of information, emotional support, cash loans, petty trade, temporary migration; women making handicrafts to sell in nearby markets and relying on friends for support (Antle, 2010)

According to FAO (2007); ACCCA, (2010) and Eid et al. (2010), people can cope up with climate variability effects through getting jobs outside agriculture, pasture preservation, reducing the herd, asking for food aid and resorting to fruit trees as a strategy to cope with the famine period. According to Ford (2006), communities can also cope up to climate variability and change by accessing alternative natural resources from forests such as charcoal burning and selling. These findings are generic and the study had to establish the coping mechanisms that households in Paicho Sub County employ in response to experienced effects of climate variability and change.

Local communities, especially dry land dwellers, have used a wide range of strategies to deal with climatic hazards such as drought. Whereas coping refers to the short-term responses that are utilized to face a sudden, unanticipated climatic risk, adaptation is a more long-term process that often entails some socio-economic and institutional changes to sustain livelihood security (Ford J (2006). Farmers have minimized or spread risks by managing a mix of crops, crop varieties and sites; staggering the sowing/planting of crops; and adjusting land and crop management to suit the prevailing conditions (Goulden, 2008; Hepworth & Goulden 2008). Pastoralists have also developed useful strategies including: transhumance (strategic movement of livestock to manage pasture and water resources); distributing stock among relatives and friends in various places to minimize the risk of losing all animals if a drought strikes one particular area; and the opportunistic cultivation of food and cash crops to meet some of their needs (Hisali et al., 2011).

In many cases, however, these adjustments in cropping and animal husbandry practices alone may not be enough to respond to climatic hazards. Increasingly, rural communities are embracing non-agricultural activities to broaden their livelihood options. Natural resources have provided a useful fallback where farming has become riskier due to increased climate variability. Gathering of forest products such as fruits, timber, medicine, firewood and honey for home consumption and for sale is becoming more important in East Africa. Kassahun, (2009) identified sixteen strategies used by the local communities in Mbitini (Kenya) and Saweni (Tanzania) locations to deal with droughts and six out of these sixteen strategies were based on the use of indigenous plant species. Other activities include making bricks for sale in urban areas and migration to more favorable areas and to urban settlements to seek paid employment (Maddison, 2006).

The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) was established by the Kyoto Protocol with the double objectives of assisting developing countries in achieving sustainable development, and assisting industrialized countries to meet emission reduction commitment (Hepworth and Goulden, 2008).

The Uganda Investment Authority which markets opportunities for CDM and carbon market investment has identified thirty sites proper for mini-hydro power investment which could generate between 10 -20 MW each and parcels of land of between 500 and 16000 hectares available for afforestation on 49-99 year leases. Some of the hydro sites are currently only marginally viable because of the level of infrastructure investment - grid extension to their isolated locations - required, and would require a subsidy to make them viable. Such assistance was lined up by the World Bank under the Rural Electrification Project but was backtracked for unknown reasons – unfortunate given Uganda’s grinding level of energy poverty (Hepworth and Goulden, 2008).

Appraisal of the Literature Review

Scholars have done lots of reviews on climate variability and change and have identified impacts and risks on crops but information is scarce on identifying climate and crop information the farmers need and for what purpose and also the available indigenous knowledge to help the farmers easily adapt to the extreme weather events. If these are addressed, it will increase the adaptive capacity of the smallholder farmers and the vulnerable. Also, identifying adaptation projects or programmes taking place in an area and suggest adaptation actions that can build more climate resilience in the area can also be a win, win solution.

Methodology

The study adopted the survey research design and simple random sampling technique was employed in the administration of questionnaire. A total of 200 farmers were randomly selected for the questionnaire administration in the four (4) sub counties (Muko, Bufundi, Nyamweru and Bubaare) that were randomly selected from a total of six (6) sub counties in Rubanda district for the study and fifty (50) questionnaires were administered in each sub county according to the procedure of Yamane (1967).

Secondary data for this study was climatic data (rainfall and temperature) data recorded for the period 1976-2016 at Kabale district meteorological center because Rubanda district was demarcated from Kabale district in 2016 and has not established its own weather station while primary data for this study was collected using structured questionnaires and field observations.

The survey was conducted to assess farmer’s perception of the impacts of climate variability and change on food security and adaptation and mitigation strategies in response to the perceived changes. This was achieved by administering a structured questionnaire. It involved a set of predetermined set of questions mainly for collecting household general data on farmer’s perception on climate variability and change impacts on food security. The data included household socio-economic characteristics, climate variability and change experiences, and adaptation and mitigation strategies in response to the impacts of climate change. Direct field observations were carried out with the help of observation checklist to validate information gathered through survey.

Inferential statistical analysis: Chi-Square was used to test whether there is variation in the perception of the impacts of climate variability and change on food security among the farmers in Rubanda District and also whether there is variation among the farmers in their perception of the impacts of climate variability and change in Rubanda District.

Figure 1: Map of study area.

Results and Discussion

Establishing the trend of Climate Variability and Change from Temperature and Rainfall records between 1976 to 2016 in Rubanda District

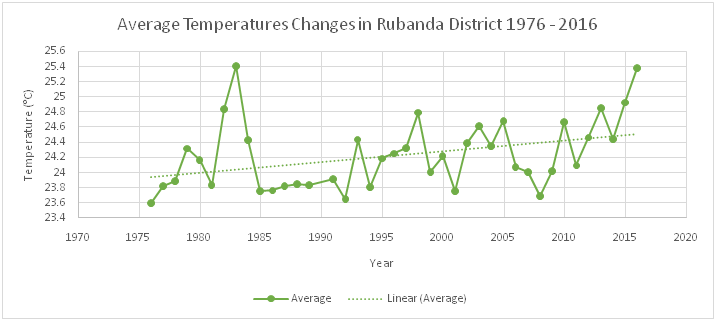

Figure 2: Average temperature Changes in Rubanda District 1976 – 2016

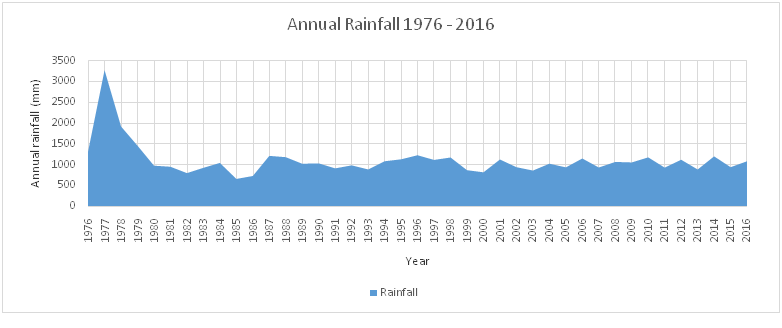

Figure 3: Annual Rain fall in Rubanda District from 1976 to 2016

Source: Source: Author’s field research 2018.

The trend analysis was based on climate data (rainfall and temperature) obtained from Kabale Meteorological weather station. The data obtained included temperature (°C) and rainfall (mm) from 1976 to 2016. These two parameters have the longest and widest data coverage in the district and are the most common climatic variables considered by many studies in Uganda. Temperature and rainfall are used for respective data collection for years and their long term values to capture climate variability and change respectively and to estimate the short and long-term effects of climate change on food security.

According to the meteorological information obtained, the forty year data (1976 - 2016) was divided into five years interval for quick analysis, interpretation and presentation on the variability of temperatures and rainfall patterns as they influence food security in Rubanda district.

The study also indicates that average temperature changes in Rubanda district has been changing overtime from 1976 to 2016. Average maximum temperature in 2016 was 25.4 degree Celsius compared to 1976 record of 23.6 degree Celsius. This shows that temperature is changing and the changes are not consistent. It can be observed that temperature started rising from 23.6 degree Celsius in 1976 and reached its peak at 24.3 degree Celsius in 1979 and then started falling at 23.8 degree Celsius in 1981. From 1985 to 1991, temperature changes were consistent with a record of 23.7 degree Celsius and 23.9 degree Celsius before it started falling at 23.6 degree Celsius in 1992. There have been rapid rising and falling of temperatures 1992 to 2016 but 2014 to 2016 has been the highest rising temperature record. The average record of temperature data from Rubanda district between 1976 and 2016 shows an increasing trend. Also, Figure 3 revealed the recorded data on rainfall from 1976 to 2016 showed a decreasing trend for the area.

In 1976 to 1986, the highest rainfall parameters recorded were 3266.3 mm during the year of 1977 compared to 484.7 mm lowest recorded in 1985. This means that between the years 1977 and 1985, there was a high variability in rainfall patterns from 3266.3 mm to 484.7 mm. This variability had a negative impact in crop production because of too much rainfall that exceeded the normal rates favorable for crop growth comparably a drastic fall in rainfall amount recorded during 1985 (484.7 mm) that was responsible for low crop production due to insufficient rainfall.

During the period of 1987 to 1996, the highest rainfall recorded was 1207.5 mm in the year 1987 compared to the lowest recorded at 881.8 mm in the year 1993. Accordingly, rainfall variability during the period of 1997 to 1996 indicates a slightly relative variability and was therefore responsible for a steady food crops production.

In the period 1997 to 2006, the highest rainfall recorded was 1144.7 mm in the year 2006, whereas the lowest was 813.1 mm realized in the year 2000. Considering the two years (2000 and 2006), higher rainfall recorded at 1144.7 mm was favorable for crop production compared to 813.1 mm which was slightly lower than the normal average rainfall required for food crop production.

The highest rainfall parameter recorded in the period from 2007 to 2016 was at 1195.5 mm in the year 2014 whereas the lowest was recorded at 880.7 mm in 2013. Rainfall variability is evidenced between the 2013 and 2014 with 2014 recording the highest rainfall totals at 1195.5mm. This means that there was a relative difference in rainfall amount received during the period 2006 to 2016 which was favorable for food crop production.

Assessment of Farmers’ perception of the Impacts of Climate Variability and Change on Food Security in Rubanda District

Table 1: Extent to which Climate Variability and Change has affected the Food Availability.

| Crosstab | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extent of Climate Variability and Change on the Food Availability | Total | |||||

| Increased | Decreased | Not Changed | ||||

| Climate Variability and Change in Rubanda district | Yes | Count | 25 | 152 | 4 | 181 |

| 13.8% | 84.0% | 2.2% | 100.0% | |||

| No | Count | 3 | 7 | 0 | 10 | |

| 30.0% | 70.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Total | Count | 28 | 159 | 4 | 191 | |

| 14.7% | 83.2% | 2.1% | 100.0% | |||

Table 1 show the extent to which Climate Variability and Change has affected the food availability. 13.8% of respondents believed that there is climate variability and change in their community and it has declining food availability, 84% also believed that there is climate variability and change in their community and believed that it has decreased the extent of declining the food availability while only 2.2% respondents thought that there is climate variability and change in their community and agreed that it has not change the extent of declining the food availability. However, about 30% of respondents believed that there is no climate variability and change in their community but claimed that climate variability and change has increased the extent of declining the food availability, while 70% of respondents believed that there is no climate variability and change in their community but agreed that climate variability and change has decreased the extent of declining the food availability.

Table 2: Chi-Square Result of Climate Variability and Change Impacts on Food Availability.

| Chi-Square Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi Square Value | Df | Sig. Level | |

| Pearson Chi-Square | 2.137 | 2 | 0.034 |

As indicated in the Chi-Square, the results show that the Climate variability and change in Rubanda District has relationship with food availability in the area (P < 0.05). This implies that climate variability and change impacts had influence on food availability in the study area during 1976 to 2016.

Climate Variability and Change has affected the food availability and access. About 26% of respondents believed that there is climate variability and change in their community and it has increased the extent of declining the food access, 71.8% also believed that there is climate variability and change in their community and believed that it has decreased the extent of declining the food access while only 2.2% of respondents thought that there is climate variability and change in their community and agreed that it has not change the extent of declining the food access. However, about 27.2% of respondents believed that there is no climate variability and change in their community but claimed that climate variability and change has increased the extent of declining the food access, 70.2% of respondents believed that there is no climate variability and change in their community but agreed that climate variability and change has decreased the extent of declining the food access while 2.6% of respondents said that there is no climate variability and change in their community but agreed that climate variability and change has decreased the extent of declining the food access. This study is in line with that of (Asiimwe & Mpuga 2007) that, most farmers’ knowledge and exposure to climate change has been influenced indirectly by the media from events occurring in distant areas.

Table 3: Perception of Impacts of Climate Variability and Change among Farmers in the four selected 4 Sub Counties

| Farmers Perception in the Sub County | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muko | Nyamweru | Bubaare | Bufundi | ||||

| Climate variability and change in Rubanda district | Yes | Count | 50 | 46 | 39 | 47 | 182 |

| 27.5% | 25.3% | 21.4% | 25.8% | 100.0% | |||

| No | Count | 0 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 12 | |

| 0.0% | 33.3% | 50.0% | 16.7% | 100.0% | |||

| Total | Count | 50 | 50 | 45 | 49 | 194 | |

| 25.8% | 25.8% | 23.2% | 25.3% | 100.0% | |||

As showed in table 3 above, the perception of impacts of climate variability and change among farmers in the four selected 4 sub counties. About 27.5% of Muko farmers believed that there is climate variability and change in their community and perceived of impacts of climate variability and change in their sub county, 25.3% of Nyamweru farmer also believed that there is climate variability and change in their community and perceived of impacts of climate variability and change in their sub county, 21.4% of Bubaare farmers thought that there is climate variability and change in their community and perceived of impacts of climate variability and change in their sub county while 25.8% of Bufundi farmers believed that there is climate variability and change in their community and perceived of impacts of climate variability and change in their sub county. However, about 25.5% of Muko farmers believed that there is no climate variability and change in their community but perceived of impacts of climate variability and change in their sub county, 25.5% of Nyamweru farmers respondents believed that there is no climate variability and change in their community but perceived of impacts of climate variability and change in their sub county, 23.2% of Bubaare farmers said that there is no climate variability and change in their community but perceived of impacts of climate variability and change in their sub county, while 25.3% of Bufundi farmers assumed that there is no climate variability and change in their community but perceived of impacts of climate variability and change in their sub county.

Table 4: Chi-square result for the Impacts of Climate Variability and Change among Farmers in the Sub Counties.

| Chi-Square Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi Square Value | Df | Sig. Level | |

| Pearson Chi-Square | 7.916 | 3 | 0.042 |

As indicated in Table 4.24, the Chi-Square result shows that there is variation in the perception of the impacts of climate variation and change among the farmers in Rubanda District (P<0.05). This implies that impacts of climate variability and change vary among the farmers in Rubanda District between 1976 and 2016.

Strategies Adopted by Farmers in Response to Climate Variability and Change in Rubanda District include: Awareness to Climate Variability and Change in the study area, Food Aid from Support Organizations, Food aid from Support Organizations and Government, Improved Crop Varieties and Animal Breeds, Improved Crops and Animal Variety Support from Organizations and Government, Water Supply Support from Organizations and Government, Rain Water Harvesting, Food Storage and Tree Planting. This study corroborates that of Howden (2007) that, in rural areas that depend on rain-fed agriculture for an important part of their local food supply, changes in the amount and timing of rainfall within the season and an increase in weather variability are likely to intensify the instability of local food systems.

Conclusion

Climate variability and change factors have the potential for climatic stress on food security in the area have been identified which include rainfall and temperature. Some aspects have been assessed with local participation to understand the extent of impacts of the climatological hazards and farmers’ perception of the impacts of climate variability and change on food security. Basic meteorological information and local knowledge on climate variability in relation to food security in Rubanda District formed the basis for the information on the farmers’ perception and the coping strategies of the communities of the impacts of climate variability and change. However, from the perspective observation of agricultural production in the 4 sub counties of the District to be realistic are seasonally faced with problems of food deficits, probably due to lack of environmental consciousness, lack of forecasts on rainfall characteristics such as onset, length of the growing season and rain days and drought length that bring about unpredicted extreme weather events like floods, landslides and drought. The study concludes that policies should be directed toward interventions to improve agriculture productivity by addressing issues concerning aspects of climate variability and change that constantly affect food security in these areas.

Recommendations

With reference to the above conclusion, the following recommendations are made.

(i) Improved access to climate forecasting and dissemination to ensure and that farmers have access to affordable credit schemes to increase their ability and flexibility to adopt adaptation measures in response to the forecasted climate conditions.

(ii) Extension services are inadequate in the study area, improving the knowledge and skills of extension service personnel and making the extension services more accessible to farmers appear to be a key element of a fruitful adaptation in the study area.

(iii) Research and Development and introduction of more new crops/varieties that more adaptive to harsh climatic conditions.

(iv) Improved soil and water conservation. Households need to enhance water harvesting techniques that promote quality and quantity that sustain crop production for long in case of drought in the future.

(v) Government should invest much in climate-dependent livelihoods. Such investments should target locations where agriculture-based livelihoods are under most pressure from climate variability and change and other environmental and social developments like the study area.

(vi) Provision of necessary technical and financial support to enhanced monitoring capabilities because of the diversity of climatic and environmental conditions especially seasonality and high annual variability of rainfall and temperature.

(vii) Finally, investment in education systems and creation of off-farm job opportunities in the area as a policy option regarding reduction of the adverse impacts of climate change in the study area.

Acknowledgments: The researcher wishes to recognize the role played by the entire staff and administration of Pan African University (Institute of Life and Earth Sciences), University of Ibadan, and African Union for the funding and Kabale University for the opportunity for further studies under staff development scheme.

References

- 1. ACCCA, Advancing Capacity to Support Climate Change. Improving decision-making capacity of small holder farmers in response to climate risk adaptation in three drought-prone districts of Tigray, northern Ethiopia Farm –Level Climate change Perception and Adaptation in Drought Prone Areas of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Project No. 093. (2010).

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 2. Adebayo, K., Dauda, T.O., Rikko, L.S., et al. Emerging and indigenous technology for climate change adaptation in the farming systems of southwest Nigeria: Issues for policy action (ATPS Technobrief No. 27). (2011) Nairobi, Kenya: African Technology Policy Studies Network.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 3. Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. (2006) Glob Environ Chang 16(3): 268–281.

- 4. Ainsworth, E.A., Ort, D.R. How do we improve crop production in a warming world? (2010) Plant Physiol 154(2): 526–530.

- 5. Antle, M.J. Adaptation of Agriculture and the Food System to Climate Change: Policy Issues. (2010) Issue Brief 10-03.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 6. Asiimwe, J.B., Mpuga, P. Implications of Rainfall Shocks for Household Income and Consumption in Uganda. (2007) AERC Paper 168. Nairobi: African Econ. Research Consortium.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 7. Awotoye, O.O., Mathew, O.J. Effects of temporal changes in climate variables on crop production in tropical sub-humid South-western, Nigeria. (2010) African J Environ Sci Technol 4(8): 500-505.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 8. Bashaasha, B., Waithaka, M., Kyotalimye, M. Climate change vulnerability, impact and adaptation strategies in agriculture in Eastern and Central Africa. (2010)

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 9. Below, T., Artner, A., Siebert, R., et al. Micro-Level Practices to Adapt to Climate Change for African Small-Scale Farmers. (2010) A Review of Selected Literature; Environment and Production Technology Division: Washington, DC, USA; p. 953.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 10. Benin, S., Thurlow, J., Diao, X., et al. Agricultural growth and investment options for poverty reduction in Uganda. (2008) Int Food Policy Res Institute, Washington, DC

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 11. Berkes, F., Jolly, D. Adapting to climate change: social-ecological resilience in a Canadian western Arctic community. (2001) Conservation Ecol 5(2): 18.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 12. Birungi, P., Hassan, R. Poverty, property rights and land management in Uganda. (2010) African J Agricult Res Economics 4(1): 48-69.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 13. Bradshaw, B., Dolan, H., Smit, B. Farm-Level Adaptation to Climatic Variability and Change: Crop Diversification in the Canadian Prairies. (2004) Climatic Change 67(1): 119–141.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 14. Cline, W. Global warming and agriculture: impact estimates by country. (2007) Centre for Global Development and Peterson, Institute for International Economics, Washington.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 15. Commission of the European Communities [CEC]. Adapting to climate change: challenges for the European agriculture and rural areas. Commission staff working document accompanying the white paper- Adapting to climate change: Towards a European framework for action. (2009)

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 16. Connolly-Boutin, L., Smit, B. Climate change, food security, and livelihoods in sub-Saharan Africa. (2016) Regional Environmental Change 16(2): 385-399.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 17. Deressa, T., Hassan, R., Ringler, C. Analysis of perception and adaptation to climate change in the Nile Basin of Ethiopia. (2008) Post graduate student at the Centre for Environmental and Policy for Africa (CEEPA). University of Pretoria.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 18. Deressa, T.T., Ringler, C., Hassan, R.M. Factors affecting the choices of coping strategies for climate extremes: the case of farmers in the Nile Basin of Ethiopia (Final START, ACCFP Report) African Climate Change Fellowship Program (ACCFP). (2010)

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 19. Intergovernmental Panel on climate change (IPCC), 2001 Third Assessment Report of IPPC, London, Cambridge University Press.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 20. IPCC Summary for policy makers. In: Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, van der Linden PJ, Hanson CE (eds) Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the inter governmental panel on climate change. (2007) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 7–22.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 21. Semenza, J.C., David, E.H., Daniel, J.W., et al. George. Public Perception of Climate Change. (2008) Am J Prev Med 35(5): 479-487.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 22. Kassahun, M.M. Climate change and crop agriculture in Nile Basin of Ethiopia: Measuring impacts and adaptation options. (2009).

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 23. Kimmerer, R.W. Weaving traditional ecological knowledge into a biological education: A call to action. (2002) Bio-Science 52(5): 432-438.

- 24. Maddison, D. The perception and adaptation to climate change in Africa. (CEEPA Discussion Paper No. 10). (2006) Centre for Environmental Economics and Policy in Africa, University of Pretoria, South Africa.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 25. Majaliwa, M., Nkonya, E., Place, F., et al. Case Studies of Sustainable Land Management Approaches to Mitigate and Reduce Vulnerability to Climate Change in Sub-Saharan Africa: The case of Uganda. (2009) International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 26. MFPED. Gender and Growth Assessment report: Uganda. A Gender Perspective On Legal and Administrative Barriers to Investment 2005. IFC Gender –Entrepreneurship –Markets. (2005) Ministry of Finance Planning and Economic Development.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 27. Molua, E.L. Turning up the heat on African agriculture: the impact of climate change on Cameroon’s agriculture. (2008) AfJARE 2(1): 45–46.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 28. National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA), 2007. MWE, Climate change Unit, Kampala, Uganda.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 29. Nzeadibe, T.C., Egbule, C.L. Chukwuone, N.A. et al. Climate change awareness and adaptation in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria (ATPS Working Paper Series No.57). (2011) Nairobi, Kenya: African Technology Policy Studies Network.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 30. U. B. O.S. Statistical Abstract. (2016) Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 31. U. B. O.S. Statistical Abstract. (2017) Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 32. UNDP, NEMA and UNEP. Enhancing the Contribution of Weather, Climate and Climate Change to Growth, Employment and Prosperity. (2009)

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 33. Seo, S.N., Mendelsohn, R. An analysis of crop choice: Adapting to climate change in South American farms. (2008) Ecol Econ 67(1): 109–116.

- 34. Republic of Uganda. The Uganda Land Policy, Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development. (2012) The Uganda Land Policy, Kampala, Uganda: The Republic of Uganda.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 35. World Bank. World Development Report 2008. (2008) World Bank, Washington DC.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 36. Yamane, Taro. Statistics: An introductory Analysis, 2nd Edition, New York. (1967)

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

- 37. Zizinga, A. Viability Analysis of Climate Change Adaptation and Coping Practices for Agriculture Productivity in Rwenzori Region, Kasese District. (2013) Makerere University: Kampala, Uganda, 2013.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others