Flavonoids as Ligands for Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ

Affiliation

Department of Zoology, Physiology Division, Beni-Suef University, Beni-Suef, Egypt

Corresponding Author

Ayman M. Mahmoud. Department of Zoology, Physiology Division, Beni-Suef University, Beni-Suef, Egypt. Tel: +201144168280; E-mail: ayman.mahmoud@science.bsu.edu.eg

Citation

Mahmoud, A.M. Flavonoids as Ligands for Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ. (2015) Int J Food Nutr Sci 2(2): 98-99.

Copy rights

©2015 Mahmoud, A.M. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Introduction

Editorial

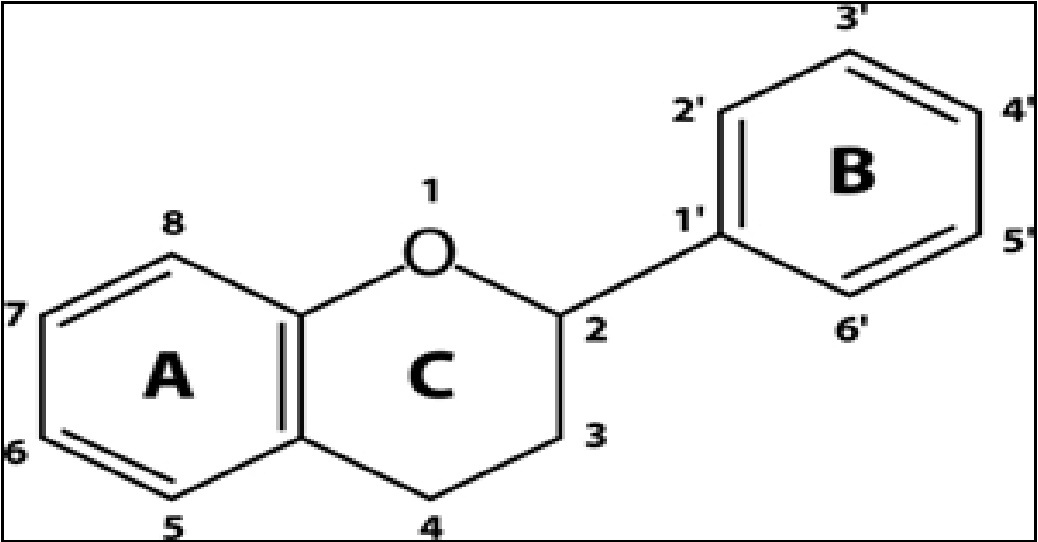

Flavonoids are non-nutritive dietary substances that are widely distributed in fruits and vegetables regularly consumed by humans[1]. They are assorted by their chemical structure into 6 subgroups as follows: flavonols, flavandiols, flavones, anthocyanins, proanthocyanidins and chalcones[2]. There are more than 6000 identified flavonoids and the number is certain to increase by further research conducted on them[3]. The chemical structure of flavonoids is based upon a 15-carbon skeleton which consists of two benzene rings (A and B) and a heterocyclic pyrane ring (C)[4], as shown in Figure 1. Flavonoids have attracted considerable interest because of their versatile health benefits including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antidiabetic, cardioprotective, hepatoprotective and anti-hyperammonemic activities[5-7].

Figure 1: Basic flavonoid structure.

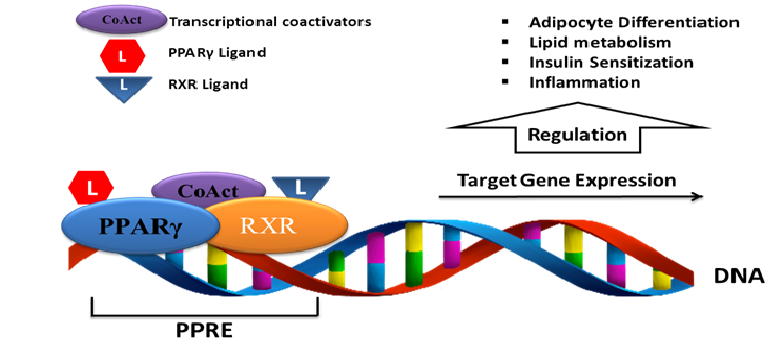

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) is a ligand-activated transcription factor that belongs to the nuclear receptors superfamily. PPARγ plays a central role in glucose and lipid homeostasis, adipocyte differentiation, inflammation[8], regenerative mechanisms and cell differentiation/proliferation[9]. Upon ligand binding, PPARγ heterodimerizes with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) in the nucleus. The PPAR-RXR complex binds to peroxisome proliferator response elements (PPREs), found in the promoters of the respective target genes, and thereby control their expression[10] (Figure2). Over the past two decades, extensive research exploring the physiological and therapeutic significance of PPARγ activation has been conducted. PPARγ is induced during the differentiation of preadipocytes and is expressed also in antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages[8]. In these cells, PPARγ regulate genes related to lipid metabolism, immunity and inflammation[11]. In addition, PPARγ activation has been reported to inhibit cancer cell growth in vitro and in animal models. Therefore, PPARγ might represent a target of paramount importance for new cancer therapies[12,13].

Figure 2: PPARγ activation pathway and transcriptional regulation of target genes.

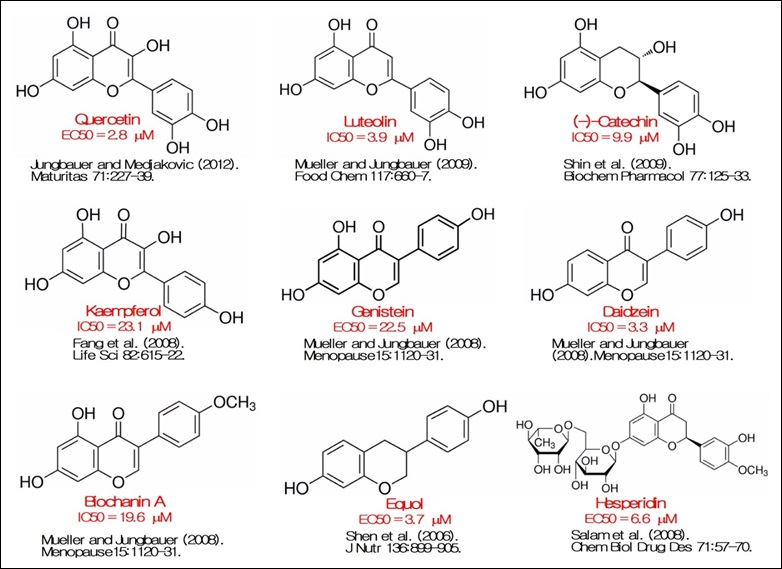

The endogenous PPARγ ligands including fatty acids and prostanoids[14] are weak agonists compared to the synthetic thiazolidinedione (TZD) agonists[15]. Hepatotoxicity, edema and cardiovascular risk related to the use of TZDs lead to their withdrawal from the market[16]. Currently, there are great research efforts to develop selective PPARγ modulators (SPPARMs) but with lower toxicity[17]. Therefore, developing natural agonists that could bind and activate PPARγ has become an absolute necessity. This might provide safe PPARγ agonists that promote health benefits without adverse effects. Flavonoids may represent a source for the discovery of novel PPARγ agonists. In this context, the study of Mueller and Jungbauer [18] reported that some main metabolites of flavonoid constituents from Trifolium pratense (red clover) bind to PPARγ with an affinity up to 100- fold higher than their precursors. A selection of flavonoids well characterized as PPARγ ligands is presented in Figure3. Flavonoids with EC50 or IC50 higher than 50 μM are not included.

Figure 3: Flavonoids activating PPARγ.

Overall, a range of PPARγ activating flavonoids were recently characterized that bear a good potential to be further investigated for therapeutic effectiveness as well as to be explored as potential dietary supplements to counteract different diseases. Many flavonoid compounds are so far not thoroughly investigated as PPARγ activators. The identification of their ability to activate PPARγ might provide further interesting agonists in the future.

References

- 1. Mahmoud, A.M. Influence of rutin on biochemical alterations in hyperammonemia in rats. (2012) Exp Toxicol Pathol 64(7-8):783-789.

- 2. Falcone Ferreyra, M.L., Rius, S.P., Casati, P. Flavonoids: biosynthesis, biological functions, and biotechnological applications. (2012) Front Plant Sci 3:222.

- 3. Ferrer, J.L., Austin, M.B., StewartJr, C., et al. Structure and function of enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of phenylpropanoids. (2008) Plant Physiol Biochem 46(3):356-370.

- 4. MiddletonJr, E. Effect of plant flavonoids on immune and inflammatory cell function. (1998) Adv Exp Med Biol 439:175-182.

- 5. Mahmoud, A.M. Hesperidin protects against cyclophosphamide-induced hepatotoxicity by upregulation of PPARγ and abrogation of oxidative stress and inflammation. (2014) Can J Physiol Pharmacol 92(9):717-724.

- 6. Mahmoud, A.M., Soliman, A.S. Rutin attenuates hyperlipidemia and cardiac oxidative stress in diabetic rats. (2013) Egypt J Med Sci 34:287-302.

- 7. Mahmoud, A.M., Ahmed, O.M., Ashour, M.B., et al. In vivo and in vitro antidiabetic effects of citrus flavonoids; a study on the mechanism of action. (2015a) Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries.

- 8. Tontonoz, P., Spiegelman, B.M. Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of PPARgamma. (2008) Annu Rev Biochem 77:289-312.

- 9. Peyrou, M., Ramadori, P., Bourgoin, L., et al. PPARs in liver diseases and cancer: epigenetic regulation by microRNAs. (2012) PPAR Res.

- 10. Yu, S., Reddy, J.K. Transcription coactivators for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. (2007) BiochimBiophysActa 1771(8):936-951.

- 11. Glass, C.K., Saijo, K. Nuclear receptor transrepression pathways that regulate inflammation in macrophages and T cells. (2010) Nat Rev Immunol 10(5):365-376.

- 12. Han, S., Roman, J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma: a novel target for cancer therapeutics? (2007) Anticancer Drugs 18(3):237-244.

- 13. Mahmoud, A.M., Abdella, E.M., El-Derby, A.M., et al. Protective effects of Turbinariaornata and Padinapavonia against azoxymethane-induced carcinogenesis through modulation of PPAR gamma, NF-κB and oxidative stress. (2015b) Phytother Res 29(5): 737-748.

- 14. Dussault, I., Forman, B.M. Prostaglandins and fatty acids regulate transcriptional signaling via the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor nuclear receptors. (2000) Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 62(1):1-13.

- 15. Cho, N., Momose, Y. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists as insulin sensitizers: from the discovery to recent progress. (2008) Curr Top Med Chem 8(17):1483-1507.

- 16. Peraza, M.A., Burdick, A.D., Marin, H.E., et al. The toxicology of ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR). (2006) Toxicol Sci 90(2):269-295.

- 17. Pirat, C., Farce, A., Lebègue, N., et al. Targeting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): development of modulators. (2012) J Med Chem 55(9):4027-4061.

- 18. Mueller, M., Jungbauer, A. Red clover extract: a putative source for simultaneous treatment of menopausal disorders and the metabolic syndrome. (2008) Menopause 15(6):1120-1131.