Let-7a as a Tumor Suppressor Modulates Invasion via Smad2 Signal in Breast Cancer

Weijuan Chen1, Hui Wang2, Chuanliang Liu3*

Affiliation

- 1Department of Pathology, The People’s Hospital of Shouguang City, Shanddong Provence, China

- 2Department of Oncology, The People’s Hospital of Shouguang City, Shanddong Provence, China

- 3Department of Health Care, The People’s Hospital of Weifang City, Shanddong Provence, China

- 4Department of Pathology, Weifang Medical University, Weifang, Shandong Province, P.R. China

Corresponding Author

Chuanliang Liu, Department of Health Care, The People’s Hospital of Weifang City, Shandong Provence, China. E-mail: chuanliang_liu@163.com

Citation

Liu, C., et al. Let-7a as a Tumor Suppressor Modulates Invasion via Smad2 Signal in Breast Cancer. (2015) Intl J Cancer Oncol 2(2): 1-4.

Copy rights

© 2015 Liu, C. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Let-7a; Tumor suppressor; Smad2; Breast Cancer

Abstract

TGF-β elicits tumor promoting effects through its ability to induce EMT which enhances invasiveness and metastasis, the perturbations of TGF-β/Smad signaling are central to carcinogenesis in most of organs. A shift in Smad2/3 phosphorylation from the carboxy terminus to linker sites is a key event determining biological function of TGF-β. Here, we showed that let-7 was associated with breast cancer development and progression by directly targeted Smad2, suggesting a tumor suppressor role of let-7 and its target Smad2 is critical regulators of TGF-β signaling in breast cancer.

Introduction

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a process implicated in cancer metastasis that involves the conversion of epithelial cells to a more mesenchymal and invasive cell phenotype. The acquisition of metastatic phenotypes by mammary tumors has been linked to the alterations in EMT[1,2]. TGF-β elicits tumor promoting effects through its ability to induce EMT which enhances invasiveness and metastasis[3]. TGF-β is implicated in the activation of tumor stromal fibroblasts, leading to the generation of CAFs and to promoting tumor stromal formation through the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway[4]. The perturbations of TGF-β/Smad signaling are central to carcinogenesis in most of organs. A shift in Smad2/3 phosphorylation from the carboxy terminus to linker sites is a key event determining biological function of TGF-β in colorectal and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Smad proteins are phosphorylated and activated by transmembrane serine-threonine receptor kinases in response to TGF-β signaling. The product of this gene forms homomeric complexes and heteromeric complexes with other activated Smad proteins, which then accumulate in the nucleus and regulate the transcription of target genes. Smad2 and Smad3 in their unphosphorylated and inactive form, reside predominantly in the cytoplasm bound to microtubule filaments and filamins[5]. TGF-β signaling induces their dissociation by phosphorylating their C-terminal domains by TbRI receptor. pSmad2 is a primary step and intracellular signaling effector for the mediation of intracellular signaling of TGF-β[6].

miRNAs, an evolutionarily conserved group of small non-coding RNAs, downregulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. The high level of conserved target motifs, seed sequences, within the 3’ UTR of the affected genes, making miRNAs powerful regulators of gene expression in numerous and complex cellular responses, including cancer cell invasion and metastasis[7,8]. Loss of let-7 in cancer results in reverse embryogenesis and dedifferentiation[9,10]. However, whether let-7 is involved in the progression of breast cancer and the underlying mechanism remains poorly understood.

In the present study, we showed that let-7 was associated with breast cancer development and progression by directly targets seed sequences in the 3’ UTRs of Smad2, suggesting a tumor suppressor role of let-7 and its target Smad2 is critical regulators of TGF-β signaling in breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

Breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), and were routinely cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco Laboratories, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Haoyang biological manufacture, Tianjin, China). The cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Plasmid construction and transfection

The sequences of let-7 mimic were as follows:

5′-UUGCAUAGUCACAAAAGUGAUC-3′ /5′-GAUCACUUUUGUGACUAUGCAA-3′. The sequence of the let-7 inhibitor was as follows: 5′-AUCACUUUUGUGACUAUGCA-3′[11]. Cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells per well in a 6-well plate and transfected using Lipofectamine according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA and protein were collected for assay 2 days post-transfection.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen), and complementary DNA was synthesized using reverse transcriptase (Sangon, Shanghai, China). Real-time quantitative PCR reactions were performed using SYBR Green (Takara, Dalian, China) For the analysis of mature let-7a, quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed using the miScript PCR System (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with let-7a primers 5′-TGAGGTAGTAGGTTGTATAGTT-3′, U6 forward 5′-CGCTTCGGCAGCACATATACTA-3′, and the universal reverse primer 5′ -GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGAC-3′. Smad2 mRNA level was quantified by qRT-PCR using Quantitect SYBR Green PCR Kit (vazyme, Nanjing, China) and normalized to β-actin with the following primers: Smad2 forward 5′-GAGGAGCAGCTCGCCAA-3′; reverse primer: 5′-CTGTCAAGGTCCGGCCAGCG-3′ for β-actin forward 5′-CCTGTACGCCAACACAGTGC-3′, and reverse 5′-ATACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCC-3′. Changes in the expression were calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

Invasion assay

Cells were serum-starved for 12 h in DMEM medium containing 0.1% FBS. Serum-starved cells were trypsinized and resuspended in DMEM containing 0.1% FBS, then 1×105 cells were added to the upper BD Matrigel invasion chambers (8 μm pore size; Corning) of 6-well plates in serum-free medium. After incubation for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, the migrated cells on the lower surface of the membrane were stained with 0.1% violet staining solution for 30min, and counted using an inverted microscope.

Smad2 3′-UTR reporter analysis

The 3′-UTR of Smad2 containing a putative let-7 binding site was amplified and cloned into pGL3 vector to generate the wild type construct. For mutant plasmid, overlap extension PCR assay was used as described previously[12]. Luciferase activities were measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Dual-Luciferase Assay System; Promega). Renilla luciferase activity was normalized to corresponding firefly luciferase activity and plotted as a percentage.

Western blot analysis

Briefly, the cells were lysed with NP40 buffer (1% NP-40, 0.15M NaCl, 50mM Tris, pH 8.0) containing protease inhibitors. Equal amounts of protein were separated on 10% polyacrylamide-SDS gel. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The blots were probed with primary antibodies, and then incubated with 1:5000 secondary antibody. The membranes were stripped and probed with monoclonal antibody for GAPDH as loading control.

Statistics analysis

The software SPSS V20.0 was used for statistical analysis. Student’s t-test and one-way ANOVA analysis were used to determine significance. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

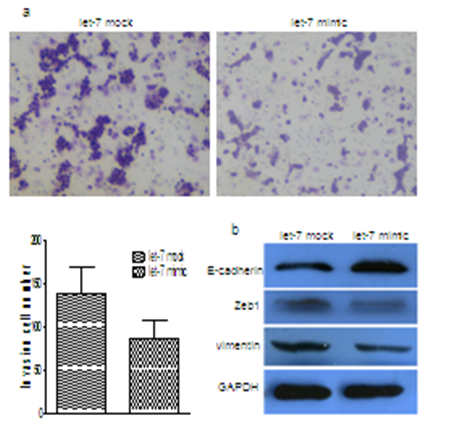

Ectopic expression of let-7a suppressed cell migration and invasion in vitro

We first examined the invasion changes in let-7a overexpressed cells. As shown in Figure 1a, We found that let-7a could significantly suppress invasion of MCF-7 cells in breast cancer cells lines. To further investigate whether the inhibitory effect of let-7a on invasion was mediated by MET, we examined the expression of MET markers. As expected, let-7 overexpression increased the expression level of E-cadherin and decreased the levels of vimentin and Zeb1 (Figure 1b).

Figure 1: Ectopic expression of let-7a suppressed breast cancer cell invasion in vitro and induced MET. (a) Effects of ectopic expression of let-7a on the invasion of MCF-7 cells. (b) MET related markers show different expression in MCF-7 cells with or without let-7a overexpression.

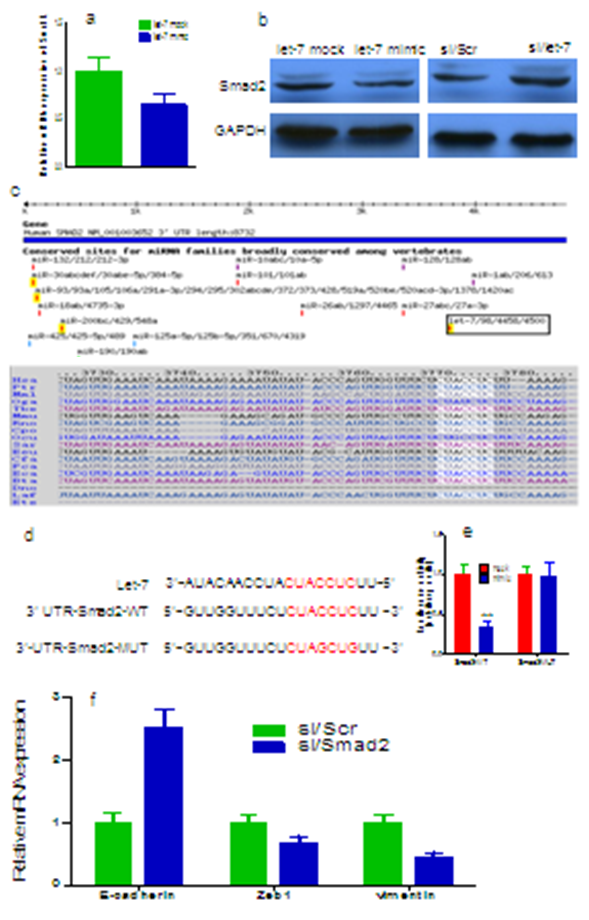

Let-7a directly targets the Smad2 3’ untranslated region (3’-UTR)

Ectopic overexpression of let-7a resulted in significantly decrease in the levels of Smad2 expression, this suppression was found both at the mRNA as observed by qRT-PCR (Figure 2a) and the protein levels as determined by Western blots (Fig. 2b). On the contrary, let-7 inhibitor restored Smad2 expression (Figure 2b). Online TargetScan program revealed that a region in the 3’-UTR of Smad2 had a perfect matching region to the seed sequence of the let-7a (Figure 2c). To confirm that the silencing of Smad2 expression is consequent to let-7a targeting of the 3’-UTR in Smad2 transcript, Smad2 3’-UTR and corresponding mutant counterparts were subcloned into pGL3 luciferase reporter vector (Figure 2d). Incubation of MCF-7 cells transfected with Smad2 promoter constructs showed suppression of luciferase activity in cells transfected with wild type 3’-UTR of Smad2 but not in cells with mutant 3’-UTR (Figure 2e).

Knockdown of Smad2 leads to the alteration of EMT markers

siRNA-targeting Smad2 was transfected into MCF-7 cells. We found that the Silencing of Smad2 in the MCF-7 cells resulted in the up-regulation of E-cadherin and down-regulation of ZEB1 and vimentin both at the mRNA and protein levels (Figure 2f). These results suggest that the Smad2 is critical for the acquisition of EMT characteristics and that the ihibition of Smad2 could reverse the EMT phenotype of breast cancer cells.

Figure 2: Smad2 is specifically targeted by let-7a (a) The alignment of the let-7a targeting sequences located in Smad2 3’-UTR. (b) let-7a overexpression reduced Smad2 protein expression in MCF-7 cells. (c) let-7a inhibitor transfection increased expression of Smad2. (d) The sequences of wild type and mutant 3’-UTR showed the segments cloned into luciferase reporter plasmid. (e) Overexpression of let-7a suppressed gradually 3′-UTR luciferase activity. (f) Knocdown of Smad2 in the MCF-7 cells resulted in the up-regulation mRNA of E-cadherin and down-regulation of ZEB1 and vimentin. **p < 0.01.

Discussion

TGF-β1 is the prototypic member of a large family of structurally related pleiotropic-secreted cytokines. The TGF-β1/ Smad signaling pathway usually participates in a wide range of cellular processes such as growth, proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. The phosphorylated receptor-regulated Smad form heterologous complexes with the common-mediator Smad4 and subsequently translocate into the nucleus to regulate the expression of target genes[13].

The mechanisms of Smad nuclear import and export have been extensively studied over the last few years, particularly in Smads 2, 3, and 4[14]. Several studies have provided evidence that Smad2 have different transcriptional functions and profiling studies have revealed distinct target genes for Smad2[15]. In a skin cancer model in mice, homozygous deletion of Smad2 in keratinocytes triggered an EMT phenotype in tumors. This was observed by downregulation of E-cadherin expression and induction of Vimentin, α-smooth muscle actin and the E-Cadherin repressor Snail[16]. We herein present data on the role of the Smad2 signaling pathway in human breast cancer and explain the potent biological effects of Smad2 on breast cancer cells. We found that silencing of Smad2 expression using siRNA resulted in the loss of TGF-β1 inhibitory effect on aromatase transcription, demonstrating that Smad2 mediates the effect of TGF-β1 on these cells.

miRNAs are discovered to play an important role in tumorigenesis and metastasis in human cancer[17]. A recent report demonstrated that miR-224 is regulated by TGF-β/Smad pathway and targets Smad4 in mouse granulosa cells[18]. The biological function of miRNA-130a on colon cancer cells is likely mediated by suppression of Smad4. Collectively, these results suggest that miRNAs are contributing to tumorigenesis by regulating TGF-β/Smad signaling, which may have potential application in cancer therapy[13].

Let-7 microRNA functions as a potential growth suppressor in human colon cancer cells[19]. Loss of let-7 function enhances lung tumor formation in vivo, strongly supporting the hypothesis that let-7 is a tumor suppressor[20]. While much work remains to be done to determine the tumor-suppressive mechanism of let-7 in in vivo lung tumors. In the current study, we found that overexpression of let-7 in breast cancer cells significantly suppressed β3 integrin in vitro, To identify the cellular target through which let-7 promotes cell proliferation we systematically screened for let-7 putative targets by integrating multiple in silico miRNA-target gene prediction algorithms, Computational prediction revealed that two evolutionarily conserved region in the Smad2 3’-UTR mRNA has a perfect complementary matching region to the seed sequence of the let-7. Luciferase activity assay indicated that let-7 could bind to the 3’-UTR sequence of Smad2 mRNA and Smad2 is a direct target of let-7.

Conclusion

These findings have important implications towards understanding that TGF-β1/Smad2 contributes to breast cancer progression. Meanwhile, our studies show that let-7, as a tumor suppressor, is a regulator of Smad2 replication in breast cancer, notably, let-7-Smad2 may represent a novel pathway for prognostic and therapeutic intervention for breast cancer.

Funding :This study was supported by grants from The Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (BS2011YY060)

References

- 1. Taylor, M.A., Davuluri, G., Parvani, J.G., et al. Upregulated WAVE3 expression is essential for TGF-beta-mediated EMT and metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer cells. (2013) Breast Cancer Res Treat 142(2): 341- 353.

- 2. Rafael, D., Doktorovova, S., Florindo, H.F., et al. EMT blockage strategies: Targeting Akt dependent mechanisms for breast cancer metastatic behaviour modulation. (2015) Curr Gene Ther 15(3): 300- 312.

- 3. Massague, J. TGF beta in Cancer. (2008) Cell 134(2): 215- 230.

- 4. Peng, Y., Li, Z. GRP78 secreted by tumor cells stimulates differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells to cancer-associated fibroblasts. (2013) Biochem Biophys Res Commun 440(4): 558- 563.

- 5. Sasaki, A., Masuda, Y., Ohta,Y., et al. Filamin associates with Smads and regulates transforming growth factor-beta signaling. (2001) J Biol Chem 276(21):17871- 17877.

- 6. Shinto, O., Yashiro, M., Toyokawa, T., et al. Phosphorylated smad2 in advanced stage gastric carcinoma. (2010) BMC Cancer 10: 652.

- 7. Harquail, J., Benzina, S., Robichaud, G.A. MicroRNAs and breast cancer malignancy: an overview of miRNA-regulated cancer processes leading to metastasis. (2012) Cancer Biomark 11(6): 269- 280.

- 8. de Krijger, I., Mekenkamp, L.J., Punt, C.J., et al. MicroRNAs in colorectal cancer metastasis. (2011) J Pathol 224(4): 438- 447.

- 9. Li, Y., VandenBoom, T.G 2nd., Kong, D., et al. Up-regulation of miR-200 and let-7 by natural agents leads to the reversal of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells. (2009) Cancer Res 69(16): 6704- 6712.

- 10. Peter, M.E. Let-7 and miR-200 microRNAs: guardians against pluripotency and cancer progression. (2009) Cell Cycle 8(6): 843- 852.

- 11. Xu, Q., Sun, Q., Zhang, J., et al. Downregulation of miR-153 contributes to epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor metastasis in human epithelial cancer. (2013) Carcinogenesis 34(3): 539- 549.

- 12. Heckman, K.L., Pease, L.R. Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. (2007) Nat Protoc 2(4): 924- 932.

- 13. Liu, L., Nie, J., Chen, L., et al. The oncogenic role of microRNA-130a/301a/454 in human colorectal cancer via targeting Smad4 expression. (2013) PloS One 8(2): e55532.

- 14. Xing, Y., Li, C., Hu, L., et al. Mechanisms of TGFbeta inhibition of LUNG endodermal morphogenesis: the role of TbetaRII, Smads, Nkx2.1 and Pten. (2008) Dev Biol 320(2): 340- 350.

- 15. Soto, P., Price-Schiavi, S.A., Carraway, K.L. SMAD2 and SMAD7 involvement in the post-translational regulation of Muc4 via the transforming growth factor-beta and interferon-gamma pathways in rat mammary epithelial cells. (2003) J Biol Chem 278(22): 20338- 20344.

- 16. Hoot, K.E., Lighthall, J., Han, G., et al. Keratinocyte-specific Smad2 ablation results in increased epithelial-mesenchymal transition during skin cancer formation and progression. (2008) J Clin Invest 118(8): 2722- 2732.

- 17. Di Leva, G., Croce, C.M. The Role of microRNAs in the Tumorigenesis of Ovarian Cancer. (2013) Frontiers in oncology 3:153.

- 18. Wang, Y., Ren, J., Gao, Y., et al. MicroRNA-224 targets SMAD family member 4 to promote cell proliferation and negatively influence patient survival. (2013) PloS One 8(7): e68744.

- 19. Sha, D., Lee, A.M., Shi, Q., et al. Association study of the let-7 miRNA-complementary site variant in the 3' untranslated region of the KRAS gene in stage III colon cancer (NCCTG N0147 Clinical Trial). (2014) Clin Cancer Res 20(12): 3319- 3327.

- 20. Esquela-Kerscher, A., Trang, P., Wiggins, J.F., et al. The let-7 microRNA reduces tumor growth in mouse models of lung cancer. (2008) Cell Cycle 7(6): 759- 764.