Management of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Patients Relatives and Intensive Care Personnel in a Teaching Hospital

Ahmed Al-Hindawi2, Klara Nenadlova2, Johnny Green3, Trudi Edginton4, Marcela Paola Vizcaychipi5

Affiliation

- 1Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care, AOU Sassari, Sassari, Italy

- 2Magill Department of Anesthesia, Intensive Care Medicine and Pain Management, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London, UK

- 3Paediatric and Adult Emergency Department, St Marys Hospital, Paddington, London, UK

- 4University of Westminster, London, UK

- 5MD, PhD, FRCA, EDICM, FFICM, Consultant in Anesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine, Honorary Senior Clinical Lecture, Divisional Research for Planned Care Surgery and Clinical Support, Magill Department of Anesthesia, Intensive Care Medicine and Pain Management, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London, UK

Corresponding Author

Angela Maria Muretti, Viale Italia 50/B, 07100, Sassari, SS, Italy, Tel: +393409658327; E-mail: angemuretti@gmail.com

Citation

Muretti, A.M., et al. Management of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Patients’ Relatives and Intensive Care Personnel in a Teaching Hospital. (2017) J Anesth Surg 4(1): 55- 64.

Copy rights

© 2017 Muretti, A.M. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Post-traumatic stress disorder; Intensive Care Unit; Psychological support service

Abstract

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a condition triggered by the experience of traumatic events and it can lead to long-term difficulties for patients and relatives in regards with their quality of life. There is growing body of evidence regarding the prevalence of PTSD amongst intensive care personnel. We set out to investigate whether there is a need for psychological support for both critically ill patients’ relatives and the intensive care unit (ICU) personnel.

Method: A prospective two-stage survey was conducted in the ICU of a teaching hospital in the United Kingdom. Two predefined questionnaires composed of closed and open questions focusing on emotional needs and individual views of psychological support were distributed to Group 1 formed by families members (Group 1A) and ICU personnel (Group 1B) in the surveySupporting Families Emotional Needs, and to Group 2 composed by ICU personnel in the survey Supporting Staff Emotional Needs.

Results: There were 77 questionnaires completed. In Group 1 there were 41 questionnaires completed on the “Supporting Families Emotional Needs” survey (16 by Group 1A and 25 by Group 1B members) and in Group 2 there were 36 questionnaires completed on the “Supporting Staff Emotional Needs” survey. Both surveys highlighted the need for a psychological support service. The design of this type of service was also investigated and was formed by opinions of the participants.

Conclusion: There is a need for additional emotion support within the ICU. Yet further work is needed to identify strategies in order to provide this support.

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder is an anxiety disorder that often follows exposure to an extreme stressor that causes injury, threatens life or physical integrity[1]. According to DSM-5 symptom criteria for PTSD, a person that is affected by this disorder

• has been exposed to death, threatened death, actual or threatened serious injury, or actual or threatened sexual violence;

• persistently exhibits intrusive symptoms (i.e. images, thoughts, perceptions, illusions, nightmares, flashbacks);

• shows persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma;

• undergoes alterations in cognitions and mood;

• reports trauma-related alterations in arousal and reactivity.

To be diagnosed, these symptoms need to persist for more than one month, the person needs to show significant symptom-related distress or functional impairment and the disturbance is not due to medication, substance or illness. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK) in “The management of PTSD in Adults and Children in Primary and Secondary Care” (2005) pointed out that although most people who have experienced a traumatic event will not develop PTSD, it is still a prevalant disorder2. The prevalence of PTSD has been studied by different research groups in several countries[2], Kessler and colleagues in a large and representative sample in the US, estimated a lifetime prevalence of PTSD of 7.8% (women 10.4%, men 5.0%) using DSM-III-R criteria[3]; Creamer and colleagues and Narrow and colleagues made estimates for 12-months prevalence range of 1.3% in Australia and 3.6% in the US, respectively[4,5].

Stein and colleagues and Andrews and colleaguesestimated that a 1-month prevalence ranged from between 1.5 - 1.8% using DSM-IV criteria and 3.4% using the less strict ICD-10 criteria[6,7]; van Zelst and colleagues analysed the prevalence of the disorder in later life and discovered that it remains common, but with the suggestion of a greater proportion of sub-syndromal PTSD in the older age group[8]. The incidence was studied by Kessler and colleagues who found that the risk of developing PTSD after a traumatic event is 8.1% for men and 20.4% for women, and Breslau and colleagues found an overall risk of PTSD to be 23.6%, and a risk of 13% for men and 30.2% for women[2,3,9,10].

The reason why PTSD is a significant problem is that it can have a very strong impact on the lives of those who develop it. The consequences of PTSD are well illustrated in the introduction of “Screening for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Primary Care: A Systematic Review” where the investigators found elevated rates of suicide, hospital admission, poverty and unemployment among those who suffer from PTSD show that they have often diminished functioning and a poorer quality of life[11-13]. Moreover, the systematic review pointed out that Andersen and colleagues found that a significant medical morbidity is also common among those with PTSD and that several age-related chronic medical conditions develop earlier[13]. The review also considered what Calhoun and colleagues and Zen and colleagues noticed among people with PTSD: they have higher prevalence rates of problematic health behaviours and utilise medical care at higher rates than those without PTSD[14,15].

Both traumatic events and genetics can be considered risk factors for PTSD. Traumatic events that can lead to PTSD include: war, natural disaster, car or plane crashes, terrorist attacks, sudden death of a loved one, rape, kidnapping, assault, sexual or physical abuse and childhood neglet. There is evidence that susceptibility to PTSD is hereditary: approximately 30% of the variance of PTSD is caused by genetic factors[16].

PTSD can develop in many different situations, and even in hospital settings. According to a recent study which analysed the relationship between critical illness and psychiatric consequences, a positive and statistically significant correlation between PTSD and hospitalisation in Intensive Care Unit was found[17]. In particular, hospitalisation in ICU increases the likehood of developing PTSD by 3.48 times, compared to treatment in another part of the hospital[17]. Parker and colleagues, conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence, risk factors and prevention/treatment strategies for PTSD symptoms in critical illness survivors, found that nearly one-quarter of ICU survivors suffer from PTSD[18].

However, patients are not the only ones who can develop PTSD in ICU, it can also affect their family members and the nursing personnel[19]. Previous studies have illustrated a close relationship between PTSD among relatives of patients admitted to Intensive Care Unit and its personnel. Azoulay and colleagues found that family members of ICU patients are at high risk of PTSD with an incidence of 33.1% and it is detectable among those who share in end-of-life decisions (81.8%)[20]. Mealer and colleagues revealed that ICU nurses have an increased prevalence of PTSD symptoms (24%) compared with other general nurses (14%)[21]. The results of these studies suggest that PTSD is a significant problem among relatives of ICU patients and ICU nursing personnel, which can lead on to have implications in their lives outside of the ICU environment.

The objectives of the study reported in this article were: (a) investigate if the family members of patients admitted to Intensive Care Unit and the ICU nursing personnel of a teaching hospital in London would benefit from psychological support; and (b) if so how it could be implemented ensuring their emotional needs are met. We have reported the outcomes of two different surveys: one investigates the families’ emotional needs from their own point of view and from the the point of view of the ICU personnel; with theother questionnaire enquiring into the emotional needs of the ICU nursing personnel.

Methods

Setting

Questionnaires were distributed in the Intensive Care Unit of a teaching hospital in central London, UK.

Time

Data collection was conducted from 11th August 2014 to 2nd December 2015. The questionnaires titled Supporting Families Emotional Needs were given to the families members and to the nursing personnel from 11th August to 1st October 2014. The questionnaire titled Supporting Staff Emotional Needs was given to the health professionals from 4th November to 2nd December 2015.

Ethic approval The study was conducted in accordance with the UK Good Clinical Practice (GCP) code of research practice, Clinical Audit Patient Panel (CAPP) Reference Number 670. All the clinical audit activity took account of the Data Protection Act (1998), Caldicott Principles (1997) and NHS Confidentially Code of Practice (2003).

Type of survey

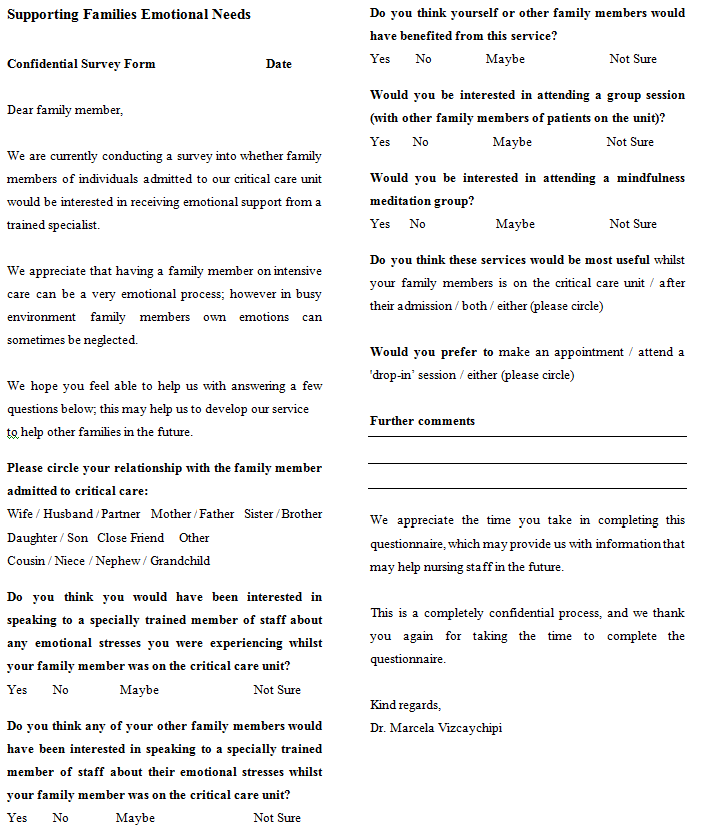

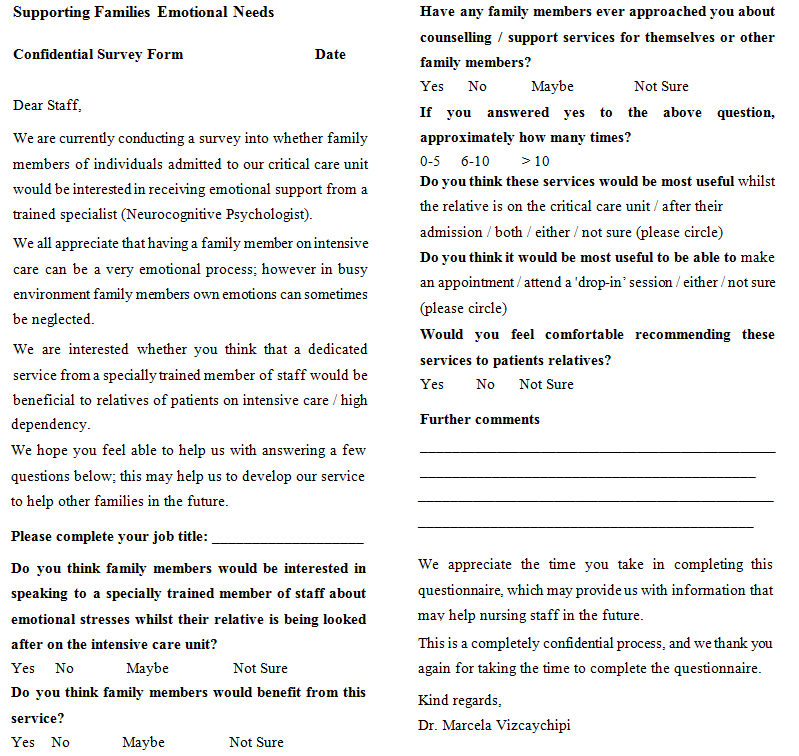

The project included two different surveys: the first intended for family members’ psychological support called “Supporting Families Emotional Needs” (Group 1) consisting of a questionnaire completed by ICU patients’ relatives (Group 1A); and another questionnaire completed by ICU personnel members with regards to patients’ relatives (Group 1B). The second survey called “Supporting Staff Emotional Needs” made for and completed by ICU personnel members (Group 2). All the three questionnaires (“Appendix”) were composed of closed and open-ended questions and they included also questions that enquired into the possible design of the support service. The questionnaires were structured into three parts: the first part asked about the relationship with the patient (for family) or the job title (for staff), in the second part there were several questions about the design of the service and the third part was used for further comments.

Results

Participants

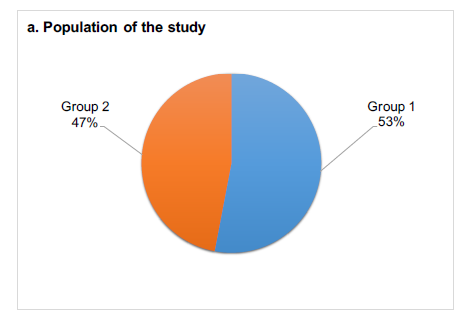

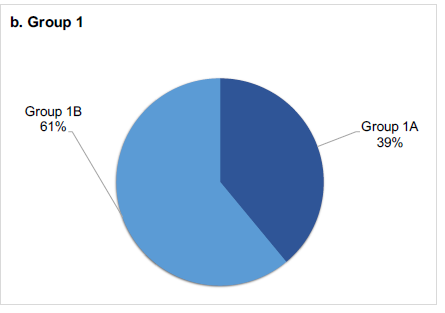

There were 77 questionnaires completed. In Group 1 there were 41 questionnaires completed on the “Supporting Families Emotional Needs” survey and in the Group 2 there were 36 questionnaires completed in the “Supporting Staff Emotional Needs” survey. Figure 1 illustrates the study population and the division of the considered groups.

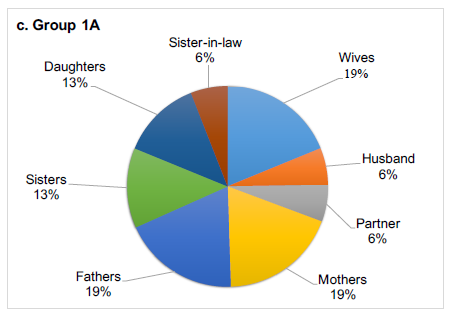

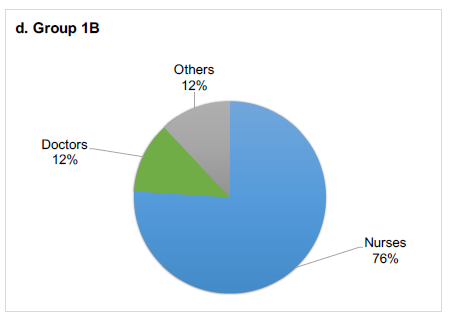

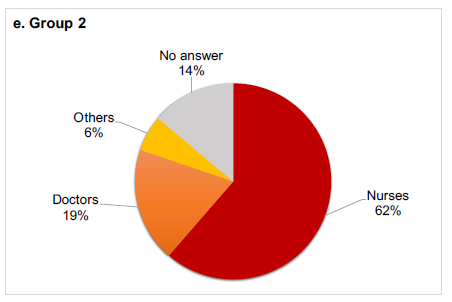

Figure 1: This figure illustrates the distribution of the study population. The pie charts represent: a) 77 participants divided into two groups, 41 (53%) in Group 1 and 36 (47%) in Group 2; b) 41 Group 1 members divided into two categories, 16 (39%) family members in Group 1A and 25 (61%) ICU personnel in Group 1B; c) Distrbution of the 16 Group 1A members based on the relationship with the patients:: 3 wives (19%), 1 husband (6%), 1 partner (6%), 3 mothers (19%), 3 fathers (19%), 2 sisters (12%), 2 daughters (12%) and 1 sister-in-law (6%); d) Distribution of Group 1B members based on the job title: 19 nurses (76%), 3 doctors (12%) and 3 other professionals represented by 1 lead divisional pharmacist and 2 physiotherapists (12%). e) Distribution of Group 2 members based on the job title: 22 nurses (62%), 7 doctors (19%), 2 other professionals represented by 1 lead divisional pharmacist and 1 physiotherapist (6%) and 5 participants have not declared their job title (14%).

Supporting Families Emotional Needs (Group 1)

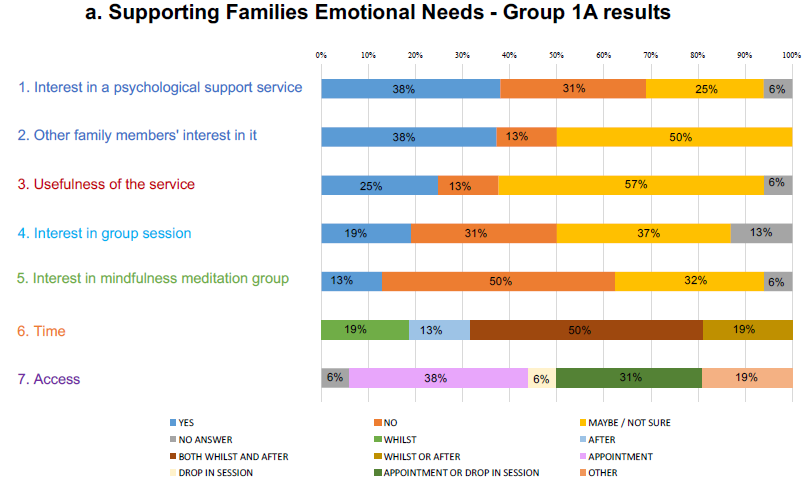

Group 1A members questionnaire results: A majority of relatives answered that they would be interested in speaking themselves (38% yes - 6 participants) or other family members (38% yes - 6 participants, 50% maybe/not sure - 8 participants) to a specially trained member of staff about any emotional stresses they were experiencing whilst the patient was on the intensive care unit, and 56% (9 participants) felt that they may benefit from this service. The possibility to attend a group session or a mindfulness meditation group were not accepted with enthusiasm: specifically, the answers to these two questions were respectively undecided (37% maybe/not sure - 6 participants) or opposed (31% no - 5 participants) to the first one and clearly contrary (50% no - 8 participants) to the second one. When family members were asked when they thought that the service could be most useful for them, the majority (50% - 8 participants) answered whilst the patient is on the ICU and after their discharge from the unit. Between making an appointment or attending a ‘drop-in’ session, the 38% of them (6 participants) chose to make an appointment.

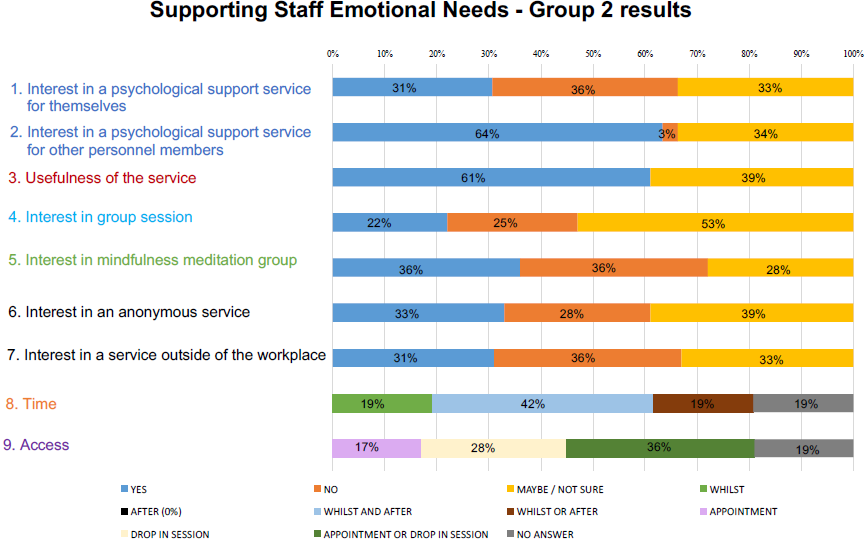

Group 1B members questionnaire results: A majority of ICU personnel (88% - 22 participants), were of the opinion that relatives would be interested in speaking to a specially trained member of the staff about any emotional stresses whilst was an inpatient on the intensive care unit and 92% (23 participants) felt that a benefit would be achieved from the support service. When they were asked about their experience on being approached about counselling or support services by family members, the majority (52% - 13 participants) said were not in favour and of those who were in favour, a large proportion stated that it happened often (58% - 7 participants) between 0 and 5 times. 88% of the personnel members (22 participants) has indicated that the support service would be most useful for relatives both during the inpatient admission and after the patient had been discharged. When asked if they thought it would be most useful to be able to make an appointment or attend a ‘drop-in’ session, the majority (44% - 11 participants) were ambivilant. Most of ICU personnel members (92% - 23 participants) said that they would feel comfortable recommending the support services to patients relatives. The answers of both Group 1A and Group 1B members are represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: This figure illustrates the questions asked to and the answers given by respondents to the first survey (Group 1). The same questions have been reported with the same colours in order to make more visible the differences between the points of view of the two groups. a) 7 questions asked to Group 1A and corresponding answers. b) 7 question asked to Group 1B and corresponding answers.

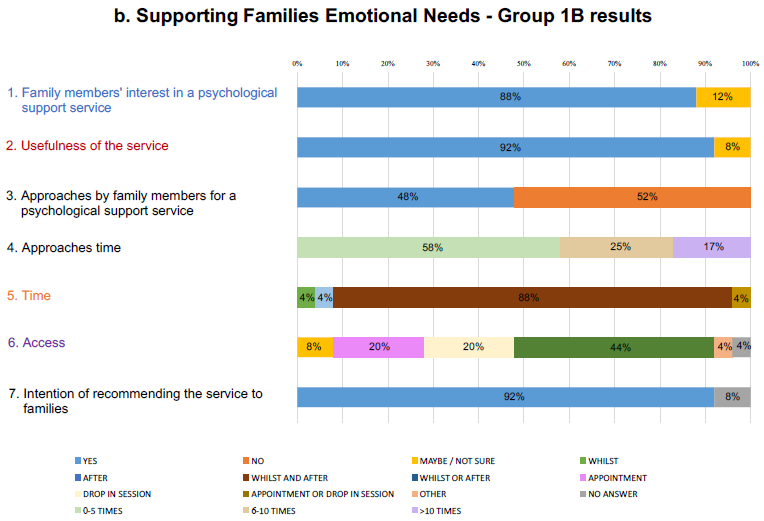

Supporting Staff Emotional Needs: Group 2 members questionnaire results 36% (13 participants) of nursing personnel answered that they would not be interested in speaking to a specially trained member of staff about any emotional stresses they were experiencing in the intensive care environment. There was, however, a marked difference in their opinion regarding other team members potential for utilising the service (64% - 23 participants). In addition they felt that other members of staff would benefit from this service (61% yes - 22 participants). While 53% (19 participants) were unsure about attending a group session, the opinions on attending a mindfulness meditation group were different: some of participants (36% - 13 participants) said that they would find it interesting, whereas 36% (13 participants) said that they would not. The questionnaire highlighted a desire for an anonymous service (33% - 12 participants), but not for a service outside of the ICU (36% - 13 participants). When asked when they thought that the service could be most useful for them, 42% (15 participants) answered both whilst in the ICU environment and after leaving. 36% (13 participants) had no preference between making an appointment or attending a ‘drop-in’ session. Figure 3 shows the results set forth above.

Figure 3: This figure illustrates the questions asked to and the answers given by respondents to the second survey (Group 2). The 9 questions are reported using the same colours coded system used in Figure 1 in order to make easily visible the difference between the personnel’s answers in the two surveys.

Comparison between the point of view of Group A, B and C members

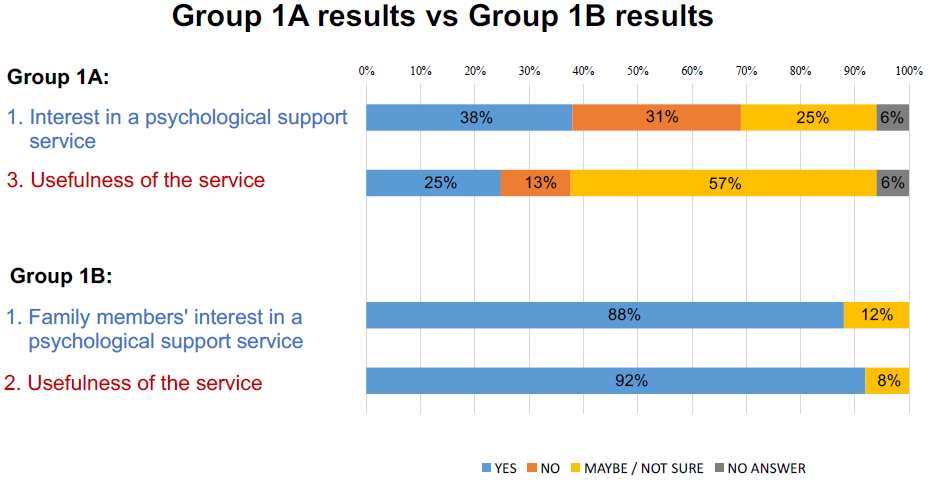

Group 1A versus Group 1B: 38% of family members (6 participants) expressed interested in speaking to a specially trained member of staff about any emotional stresses experiencing whilst their loved ones are on the ICU, likewise 88% of ICU staff (22 participants) thought that the relatives would positively benefit. Although participants in both groups agree that family members would benefit from speaking to a specially trained member of staff, it occurs in two different percentages. However, only 25% of ICU patients’ family members (4 participants) compared to 92% (23 participants) of ICU staff members, stated that they would recommend these services to patients’ relatives. In Figure 4 is shown the comparison between the results obtained in the two groups analysed.

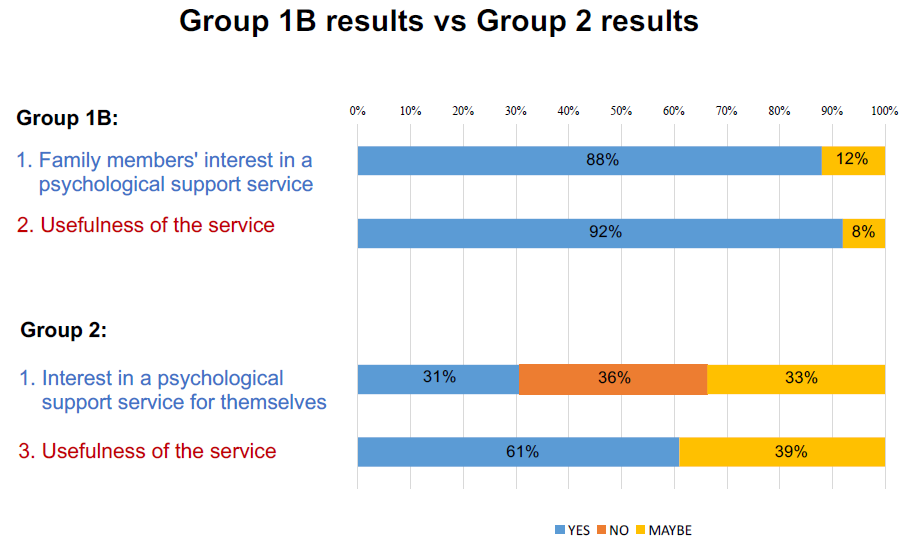

Group 1B versus Group 2: While 88% (22 participants) thought that the relatives of ICU patients would be interested in a psychological support service, 36% (13 participants) felt that they themselves would not be interested in speaking to a specially trained member. The majority of the ICU personnel consider psychological service useful, but with differing degree depending on the subject group: 92% of the personnel (23 participants) felt that the patients’ relatives would benefit from this service,61% of them (22 participants) thinks that it would be useful for themselves. Figure 5 shows the differences between the results of questionnaires given to ICU personnel members in the first and in the second survey.

Figure 4: Comparison between the point of view of Group 1A and Group 1B members. In the upper part of the figure are shown the Group 1A members’ answers to the questions 1 and 3 of the survey “Supporting Families Emotional Needs” for family members. The percentages of their positive response (38% to question 1 and 25% to question 3) are lower than the Group 1B members’ ones and the presence of negative responses (31% to questions 1 and 13% to question 3) and of undecided responses (25% to question 1 and 56% to question 3) indicate that, although the majority thinks that such a service would be useful and they would use it, many of them are not convinced of this. In the lower part of the figure are shown the Group 1B members’ answers to the questions 1 and 2 of the survey “Supporting Families Emotional Needs” for ICU staff members. The percentages of their positive responses (88% to question 1 and 92% to question 2) indicate that they believe in the utility of a support service for families.

Figure 5: Comparison between the point of view of Group 1B and Group 2 members. In the upper part of the figure are shown the Group 1B members’ answers to the questions 1 and 2 of the survey “Supporting Families Emotional Needs” for ICU personnel. The percentages of their positive responses (88% to question 1 and 92% to question 2) indicate that they believe in the utility of a support service for families. In the lower part of the figure are shown the Group 2 members’ answers to the questions 1 and 3 of the survey “Supporting Staff Emotional Needs”. 31% of them answered to question 1 that they would use the support service and 36% gave negative response. Most of Group 2 members (61%) are convinced that a support service would be useful for themselves and other personnel members (question 3).

Discussion

The general opinion regarding psychological support service from participants was a positive one. What emerges from the comparison between the answers of the two different considered groups in the survey “Supporting Families Emotional Needs”, is that their position on psychological support is different. Fewer than expected participants expressed interested in speaking to a specially trained member of staff about any emotional stresses experiencing whilst their relatives are on the ICU. This is in contrast to the majority of ICU personnel who thought that the relatives would indeed benefit positively. Although this view was reflected by the majority of participants in both groups, it occurs to different degrees, as discussed above.

However, even though staff responded positively to the introduction services for patients relatives, they were not so forthcoming regarding needing to use the service themselves. The majority felt it would be positive for relatives, and aid in the processing of the events that take place in the intensive care unit. However, the number of personnel who expressed interest for themselves was lower; yet many would consider referring a colleague to the service. From this stark difference in sentiment, we can infer that there is a definite need for psychology support services for both medical staff and relatives. Yet interestingly, the strategies for utilising the services need to enable the people who need them the most to feel free and able to access the service.

The difference between the two opposite positions of the ICU staff represented in the two surveys reflects the individual interpretation of need for services depending on their point of view: the professional one with the attitude to give help (Group 1B) and the human one with the ability to accept help (Group 2). For both ICU patients’ family members and ICU personnel it appeared to be difficult to admit that they may needed help for themselves and as Stephen Brett explained in the foreword to NICE clinical guideline 83 - Rehabilitation after critical illness (page 6), “it was recognised that information around social services and benefits is often difficult to obtain and understand by those who need it”[22]. The difficulty in admitting PTSD was well highlighted in a passage of the Robert N. McLay’s book “At war with PTSD: Battling Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder with Virtual Reality” in which the author wrote “There are many reasons someone would or would not believe in PTSD. Truth is a hard thing to get to. I have always liked the philosopher William James’s take on the subject. He said that things are true to the extent they are useful. PTSD is a useful concept. It should not define who a person is or give anyone the excuse to fail, but it can give a pattern for recovery. If trauma had nothing to do with symptoms, then confronting trauma would not help a person to overcome her problems. But it does.”[23]. Although, as the surveys results show, both ICU patients’ relatives (Group 1A) and ICU personnel (Group 2) found it difficult to admit to needing help. It is important therefore to ascertain the best ways of providing support for them. All questionnaires in this study included some specific questions aimed to aid the design of a suitable service.

In the survey “Supporting Families Emotional Needs” the majority of each group agrees that the support services would be useful both whilst as an inpatient and after discharge (50% of relatives - 8 participants, 88% of staff - 22 participants). Between attending a ‘drop-in’ session or making an appointment, most of family members (38% - 6 participants) prefer to make an appointment; conversely most of staff members suggest either to make an appointment and to attend a ‘drop-in’ session (44% - 11 participants). Further in the survey “Supporting Staff Emotional Needs” the ICU personnel members (42% - 15 participants) thought that the support service would be useful both whilst working on the ICU and after leaving the ICU environment. The most appropriate service in the personnel members’ opinion was to either make an appointment or attend a ‘drop-in’ session (36% - 13 participants). Moreover, 33% (12 participants) of ICU personnel were interested in an anonymous service, but not out of the workplace (36% no - 13 participants).

As results show, the most suitable service for all of participants should be readily available in the Intensive Care Unit, with the option of either making an appointment or attending a ‘drop-in’ session. This second option, as some of them have specified in the comments, would allow them to utilise the service on a more immediate and ad hoc basis, allowing them to address emotional stress in the acute phase, without the commitment of making an appointment. The surveys proposed two forms of psychological support therapies: attending a group in session and attending a mindfulness meditation group. Neither were enthusiastically embraced by either participant groups, but the group sessions were received positive by the personnel group. With regards to ‘drop-in’ and scheduled opportunities, both personnel and relatives expressed this would be the most suitable path to accessing services.

It is clear that there is no single way to combat PTSD that would fit every person. The support service proposed within this article may increase the chance of addressing PTSD in its sufferers, giving them the possibility to find the most suitable form of support which would be tailored to their needs. It is important to acknowledge the PTSD sufferer’s input regarding the type of support service given, as well as that of patients’ family members and ICU nursing personnel.

Analysis of participants’ comments Studying the comments of the two questionnaires is vital to better understand the best way of supporting the participant groups. Overall, the comments were positive and they revealed that many participants consider the psychological support for people with PTSD a good idea. Among family members, several of the participants wrote further comments, and from the these we can firstly notice that they appreciate the work of the nursing staff members. However, many commented that having the opportunity to discuss issues with an experienced specialist and also having a time for a discussion where questions can be asked and answered would be valuable.

Nearly half of the staff members sustained the need for emotional support for family members with comments. One of them wrote that a ‘drop-in’ session may feel less formal and take any feelings of pressure about the meeting off the family members. Another wrote that they would feel comfortable recommending this service to patients’ relatives, but it might be better if the service introduced themselves informally at the bedside.

Personnel comments showed a positive appreciation towards the idea of having psychological service available on the unit, with some noting that it would be particularly useful after a patient’s death or demanding shift. Some stated that they did not feel the need for a psychological support service themselves, but it would be useful for other members of their team who encounter stress or stress related illness. The most concerning comment said that ‘it would have been nice if someone for once would have thought about the nursing staff’ this demonstrates a clear need to provide urgent support service in the Intensive Care Unit.

Conclusion

Research states that both relatives of ICU patients and the personnel caring for them are at high risk of develop PTSD symptoms. It is important to address this gap in the holistic care of the patient, their families but also staff members, this could be done with the introduction of a support service available in the Intensive Care Unit. Nowadays there are many therapies and psychological treatments for adults with PTSD, as Cusack et al. Analysed[24]. The collaboration between patients and researchers is an important step towards finding best strategies to be taken against this disorder. Although PTSD presents with a wide array of symptoms and presentations, it is key to address them for every person who has contact with the intensive care environment. It is challenging; however, by providing a safe and qualified environment to address such issue, we hope to alleviate the challenges that PTSD can present in an intensive care situation. It is also important to note that further research is need to not only evaluate the effeteness of any proposed changes, but also address the wider aspects cased by PTSD.

The study has provided insight into the types of services which are considered helpful by these different groups, however more research is needed to varify the usefulness of such a support service.

Acknowledge:

We would like to thank all the ICU staff members at the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital and the ICU patients’ relatives that took part in the surveys making possible the realisation of this study. We would like to acknowledge all the Dr Vizcaychipi’s team members that have helped us to achieve these results. In particular, we thank Dr Edward Watson for the great help to give the questionnaires to the staff members in the Intensive Care Unit and Dr Sundhiya Mandalia for the support in the statistical processing of data.

Conflict of interest:

authors declare that there are not conflicts of interest.

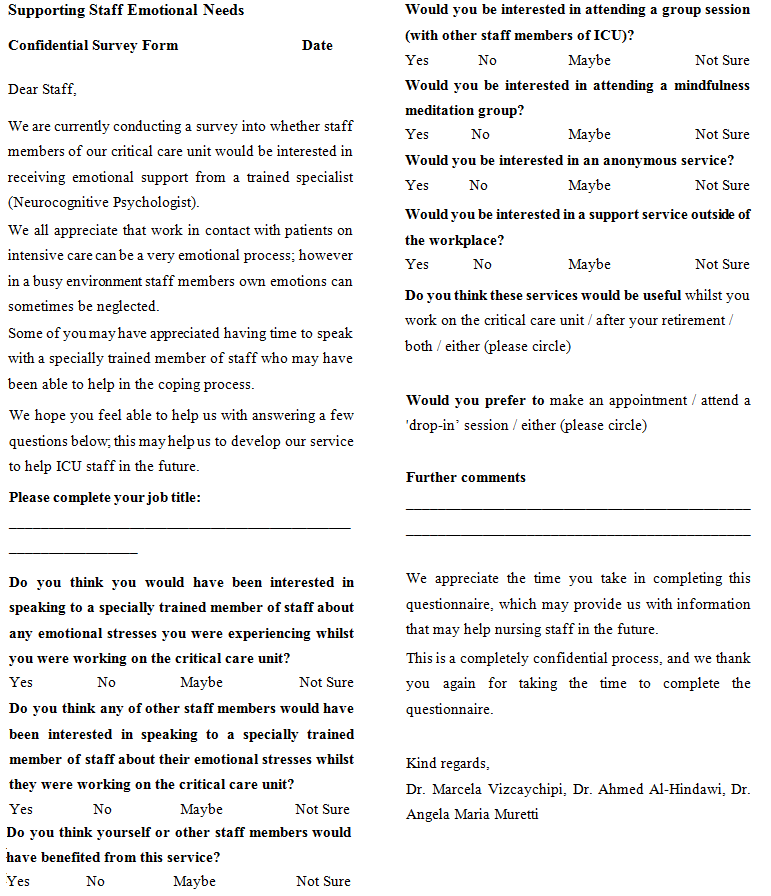

Appendix: Below are reported the questionnaires that were distribuited to the study participants: Group 1A questionnaire is shown in figure 6, Group 1B in figure 7 and Group 2 in figure 8.

Figure 6: “Supporting Families Emotional Needs” survey: questionnaire delivered to family members (Group 1A).

Figure 7: “Supporting Families Emotional Needs” survey: questionnaire distribuited to ICU personnel (Group 1B).

Figure 8: “Supporting Staff Emotional Needs” survey: questionnaire given to ICU personnel (Group 2).

References

- 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). (1994) Washington, DC.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 2. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health UK. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. The Management of PTSD in Adults and Children in Primary and Secondary Care (2005).

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 3. Kessler, R.C., Sonnega, A., Bromet, E., et al. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. (1995) Arch Gen Psychiatry 52(12): 1048–1060.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 4. Creamer, M., Burgess, P., McFarlane, A.C. Post-traumatic stress disorder: findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. (2001) Psychological Medicine 31(07): 1237–1247.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 5. Narrow, W.E., Rae, D.S., Robins, L.N., et al. Revised Prevalence Estimates of Mental Disorders in the United States: Using a Clinical Significance Criterion to Reconcile 2 Surveys' Estimates. (2002) Arch Gen Psychiatry 59(2): 115–123.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 6. Stein, M.B., Walker, J.R., Hazen, A.L., et al. Full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from a community survey. (2006) Am J Psychiatry 154(8): 1114–1119

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 7. Andrews, G., Slade, T., Peters, L. Classification in psychiatry: ICD-10 versus DSM-IV. (1999) Br J Psychiatry 174: 3-5

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 8. van Zelst, W.H., de Beurs, E., Beekman, A.T.F., et al. Prevalence and risk factors of posttraumatic stress disorder in older adults. (2003) Psychother Psychosom 72(6): 333–342.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 9. Breslau, N., Davis, G.C., Andreski, P., et al. Traumatic Events and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in an Urban Population of Young Adults. (1991) Arch Gen Psychiatry 48(3): 216–222.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 10. Breslau, N., Davis, G.C., Andreski, P., et al. Sex Differences in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. (1997) Arch Gen Psychiatry 54(11): 1044–1048.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 11. Spoont, M., Arbisi, P., Fu, S., et al. Screening for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Primary Care: A Systematic Review. (2013) Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs (US).

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 12. Andersen, J., Wade, M., Possemato, K., et al. Association Between Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Primary Care Provider-Diagnosed Disease Among Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans. (2010) Psychosom Med 72(5): 498–504.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 13. Yaffe, K., Vittinghoff, E., Lindquist, K., et al. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Risk of Dementia Among US Veterans. (2010) Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(6): 608–613.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 14. Calhoun, P.S., McDonald, S.D., Guerra, V.S., et al. Clinical utility of the Primary Care - PTSD Screen among U.S. veterans who served since September 11, 2001. (2010) Psychiatry Research 178(2): 330–335.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 15. Zen, A.L., Whooley, M.A., Zhao, S., et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder is associated with poor health behaviors: Findings from the Heart and Soul Study. (2012) Health Psychol 31(2): 194–201.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 16. True, W.R., Rice, J., Eisen, S.A., et al. A Twin Study of Genetic and Environmental Contributions to Liability for Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms. (1993) Arch Gen Psychiatry 50(4): 257–264.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 17. Asimakopoulou, E., Madianos, M. Depression and post-traumatic stress disorder among patients in intensive care units. (2014) Psychiatriki 25(4): 257–269.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 18. Parker, A.M., Sricharoenchai, T., Raparla, S., et al. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Critical Illness Survivors: A Metaanalysis. (2015) Crit Care Med 43(5): 1121–1129.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 19. Wade, D.M., Howell, D.C., Weinman, J.A., et al. Investigating risk factors for psychological morbidity three months after intensive care: a prospective cohort study. (2012) Crit Care 16(5): R192.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 20. Azoulay, E., Pochard, F., Kentish-Barnes, N., et al. Risk of Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms in Family Members of Intensive Care Unit Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2005) 171(9): 987–994.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 21. Mealer, M.L., Shelton, A., Berg, B., et al. Increased Prevalence of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in Critical Care Nurses. (2012) Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175(7): 693–697.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 22. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. NICE clinical guideline 83. (2013) Rehabilitation after critical illness 1–91.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 23. McLay, R.N. At War with PTSD. Battling Post Traumatic Stress Disorder with Virtual Reality. (2012) 216.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 24. Karen Cusack et al. Psychological Treatments for Adults with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. (2015) Clinical Psychology Review 43: 128–141.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others