Omega-3 Fatty Acids Improve Lipid Metabolism and Inflammatory Markers in Patients with Heart Failure Undergoing Exercise Training

Fernanda da Silva Casagrande, Vitor Giatte Angarten, Anderson Zampier Ulbrich, Raul Cavalcante Maranhao, Tales de Carvalho

Affiliation

1Post-Graduation Program in Nutrition of the Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianopolis, Florianopolis-SC, Brazil

2Post-Graduation Program in Science of Human Movement of the State University of Santa Catarina, Florianopolis-SC, Brazil

3Lipid Metabolism Laboratory, Heart Institute (InCor) of the University of São Paulo Medical School, Sao Paulo-SP, Brazil

4Department of Clinical Analyses, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianopolis- SC, Brazil

Corresponding Author

Edson Luiz da Silva, Department of Clinical Analysis, Health Sciences Center, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Campus, s/n, Trinity, 88.040-370, Florianópolis, SC, Brazil. Telephone: +55-48-3721-97.12; Fax: +55-48-3721-5072; E-mail:edson.silva@ufsc.br; dasilvael@hotmail.com

Citation

da Silva, E. L. et al. Omega-3 Fatty Acids Improve Lipid Metabolism and Inflammatory Markers in Patients with Heart Failure Undergoing Exercise Training. (2015) J Food Nutr Sci 2(1): 70-75.

Copy rights

© 2015 da Silva, E. L. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Heart failure; Omega-3 PUFA; Exercises training, Lipid profile; Inflammatory markers

Abstract

We hypothesize whether omega-3 (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) supplementation may improve the lipid metabolism and inflammatory biomarkers in heart failure (HF) patients undergoing exercise training. Sixteen male patients, who were participating in a physical cardiac rehabilitation program, ingested 4.8 g of fish oil daily (2.51 g of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids) for 60 days. Blood samples were collected at baseline and after 60 days of n-3 PUFA supplementation for analysis. The paired Student t-test was applied to detect differences (p < 0.05). The n-3 PUFA significantly reduced the levels of triglyceride (28.9%), small dense LDL- cholesterol (16.2%), non-HDL-cholesterol (9.0%), and TNF-α (17.8%) after 60 days (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the transfer of cholesteryl-ester to HDL increased by 23.1% (p < 0.05). In summary, the n-3 PUFA supplementation improved the lipid metabolism and low-grade systemic inflammation in HF patients submitted to exercise training, which may lower the risk of cardiovascular events.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is considered the final pathway of several cardiovascular 101 diseases (CVD), contributing substantially to public health costs worldwide[1,2]. Guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation have recommended supervised exercise programs for CVD patients as a non-pharmacological approach which also improves the inflammatory and lipid profiles, decreases morbidity and mortality rates and reduces re-hospitalization rates[1,3,4]. In HF, exercise training has been considered as an effective non-pharmacological treatment to improve the life quality of the patients and the outcomes and reduce mortality[1,3]. Several mechanisms have been described for these effects, including regression of atherosclerosis lesion in monkeys[5], which was likely achieved by ameliorating dyslipidemia, reducing vascular inflammation, adiposity, endothelial dysfunction and blood pressure, and increasing insulin sensitivity[5,6]. Although standard training programs are safe and cost-effective, cardiac rehabilitation is not recommended by all physicians and is still underused in some countries[7,8]. In addition to exercise training, supplementation with omega-3 (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) has also been of potential interest as a therapy for CVD and HF patients[9-13]. A considerable amount of evidence supports the potential benefits of n-3 PUFA in patients with HF[14-18]. The mechanisms implicated in such benefits are complex and not well defined. However, several pathways have been identified, including improvement of the serum lipid profile[19], regulation of gene expression involved in the myocardial fatty acid uptake and metabolism[20], elevation of plasma levels of adiponectin and reduction of cytokines[21,22].

In this context, exercise programs and some non-pharmacological approaches, including n-3 PUFA supplementation, have been independently explored in order to control and minimize the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with heart disease such as HF. However, to the best of our knowledge, the beneficial effects of n-3 PUFA have not been investigated in HF patients undergoing complete medical treatment, i.e, pharmacological therapy and exercise training. Therefore, herein, we hypothesize whether n-3 PUFA supplementation could promote additional improvement of serum lipid metabolism and decrease inflammatory biomarkers in HF patients participating in a cardiac physical exercise program and who have stable plasma biochemical parameters. The primary end points were absolute or percentage change in serum levels of lipid parameters, in vitro transfer of lipids to high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and changes in serum levels of the inflammatory biomarkers ultrasensitive C-reactive protein (us-CRP), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-1, IL-6, IL-10, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α).

Methods and Subjects

Sixteen eligible volunteers (men) with a clinical diagnosis of ischemic, hypertensive or idiopathic heart failure and enrolled in the Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation Program of the State University of Santa Catarina, Florianopolis - SC, Brazil, for at least 3 months[23], participated in the study. Prior to n-3 PUFA supplementation, HF patients were evaluated over 30 days for baseline monitoring of the serum biochemical parameters. After this period, HF patients consumed four capsules of fish oil (Fish Oil Double Strength® –Nature´s Bounty, Bohemia, NY, USA) daily, totalizing 2.51 g of docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid in a ratio of 1.0:1.83, over 60 days. Compliance with n-3 PUFA supplementation was measured weekly during the study. All HF subjects performed supervised exercise three times a week at the same intensity and frequency throughout the study. Activity sessions were comprised of 10 min of warm-up articulation and stretching, 40 min of continuous aerobic exercise and finally 5 min of relaxation and stretching. The exercise intensities were previously determined by a cardiopulmonary exercise test, according to the heart rate equivalent to the anaerobic threshold. During the sessions, the heart rate was controlled by a RS800 heart rate monitor (Polar-Kempele, Finland) in order to ensure that the patient was within his training target zone. At baseline (0 day) and after 30 and 60 days of n-3 PUFA supplementation, blood samples were collected for biochemical analysis. In addition to blood collections, anthropometric data collection, clinical evaluation, a check of compliance, and dietary intake assessment through 3-day food reports were also performed. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki principles and all participants read and signed informed consent forms before any study procedures were performed. The study protocol was approved by the appropriate committee of the Federal University of Santa Catarina (number 05977212.4.0000.0121). Heart failure was diagnosed by ejection fraction < 55%[1], and the recruited patients were classified as functional class II or III[24]. Exclusion criteria were patients who were unstable, undergoing medication adjustments, smokers, suffering from untreated hypertension, kidney, thyroid or liver diseases or suffering from cancer, as well as patients using anti-inflammatory medications or dietary supplements containing n-3 fatty acids, vitamins or minerals.

Laboratory Methods

Blood samples were collected after 12h overnight fasting in tubes without additives for serum isolation by centrifugation (750 x g, 10min). Total cholesterol and triglyceride were determined by routine enzymatic methods[25,26] using Lab test reagents (Lagoa Santa-MG, Brazil). HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) was measured by homogeneous reagent[27] and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) was estimated according to the Friedewald formula for triglyceride levels < 4.52 mmol/L[28]. For samples which were found to contain levels of riglyceride > 4.52 mmol/L, LDL-C was directly measured by the homogeneous LDL-C method (Labest – Lagoa Santa - MG, Brazil)[29]. In order to minimize the variation, the direct LDL-C method was used for all serum samples of the patients who had triglyceride > 4.52 mmol/L, i.e., samples collected before and after n-3 PUFA treatment. The lipid analysis was carried out in automated equipment (Cobas-Mira Plus – Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Non HDL-C was calculated as the difference between total cholesterol and HDL-C. The concentrations of IL-1β, IL-1, IL-6, IL-10, MCP-1, VEGF, and TNF-α were determined by the Luminex® 200 method (xMAPtechnology, Austin, Texas, USA), using the commercial kit HCYTOMAG-08-60K (MilliplexMap, Millipore, Missouri, USA)[30], according to the manufacturer´s instructions, and the us-CRP was measured by immunonephelometry (DadeBehring BNII nephelometer, Siemens Healthcare Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfield, Illinois, USA)[31].

Measurement of sd-LDL

The more atherogenic particle small, dense-LDL (sd-LDL) was determined using the homogeneous LDL-C reagent (Labest – Lagoa Santa-MG, Brazil) after selective precipitation of the other serum apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins, including the large buoyant LDL particles, with heparin and magnesium according to the procedure described previously by Hirano et al.[32] and modified by Cavalcante and Silva[33]. Briefly, serum samples (0.1 mL) were vortex mixed (30 s) with 150 IU/mL heparin-sodium and 90 mmol/L magnesium chloride (0.1mL) and incubated at 37ºC for 10 min. The samples were kept in an ice bath for 15 min and the tubes were then centrifuged (9,500 x g, 15 min, 4ºC). The supernatant containing the sd-LDL and HDL particles was collected and sd-LDL-cholesterol (sd-LDL-C) was directly and selectively measured by the homogeneous method for LDL-C, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Serum samples containing triglyceride levels > 3.39 mmol/L were diluted by a factor of 1.2 with 100 mmol/L phosphate buffer pH 8.5[33] and the sd-LDL was isolated and measured as described above.

Lipid Transfer from LDL-Like Nano-Emulsion to HDL In-vitro

The in vitro assay of the simultaneous transfer of radioactively- labeled phospholipid (PL), triglyceride (TG), free cholesterol (FC), and cholesteryl-ester (CE) from an artificial nanoemulsion to the HDL plasma fraction was performed as described by LoPrete et al.[34]. Briefly, the donor lipid nanoemulsions containing 3H- cholesteryl oleate and 14C-phosphatidyl choline or 3H-triolein and 14C-cholesterol were incubated with whole plasma in an orbital shaker (GyromaxTM 70GR, Amerex, Lafayette, CA) for 1h. After chemical precipitation of the nanoemulsion and the apolipoprotein B-lipoprotein fractions using 0.2% dextran sulfate and 0.3 mol/L (v/v) magnesium chloride, the supernatant containing the HDL fraction was subjected to radioactivity counting in a scintillation solution using a Packard 1600 TR model Liquid Scintillation Analyzer (Palo Alto, CA). The percentage radioactivity of each lipid (TG, CE, FC, and PL) transferred from the nanoemulsions to HDL was then estimated.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD), while categorical data were expressed as absolute and relative frequency. Data normality was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For variables that presented Gaussian distribution (directly or after logarithmic transformation), the differences promoted by n-3 PUFA supplementation were detected by applying the paired Student's t-test. For variables that presented a non-Gaussian distribution, the Wilcoxon test was used. The Pearson's correlation was considered to verify an association between serum levels of triglyceride at baseline and after n-3 PUFA supplementation.

A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All calculations were performed using SigmaPlot 12.0 (Systat Software Inc. (SSI), San Jose, California, USA). This study is registered with Universal Trial Number (UTN) U1111-1139- 3286.

Results

Subject characteristics eighteen subjects were recruited to participate in the study but two patients did not complete the intervention period for personal reasons and were excluded from the study. Thus, 16 male volunteers with HF effectively participated in the intervention trial. All patients followed the experimental protocol and adverse effects of n-3 PUFA consumption were not reported. The clinical features and biodemographic characteristics of the participants are given in Table 1. The daily energy and nutrient intake estimated from the 3-day food record did not differ after each period (results not 252 shown).

Table 1: Physical and clinical characteristics of the heart failure patients at baselinea.

| Age (years) | 58.8 ± 1.2 |

|---|---|

| Body mass index (kg/m²) | 29.9 ± 1.1 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 98.9 ± 3.0 |

| Smoking habit, n (%) | 1(6.2%) |

| Ex-smokers, n (%) | 9 (56.2%) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 15(93.7%) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 3 (18.7%) |

| Familial history of CVD, n (%) | 14(87.5%) |

aValues are means ± SD (n = 16). CVD = Cardiovascular disease.

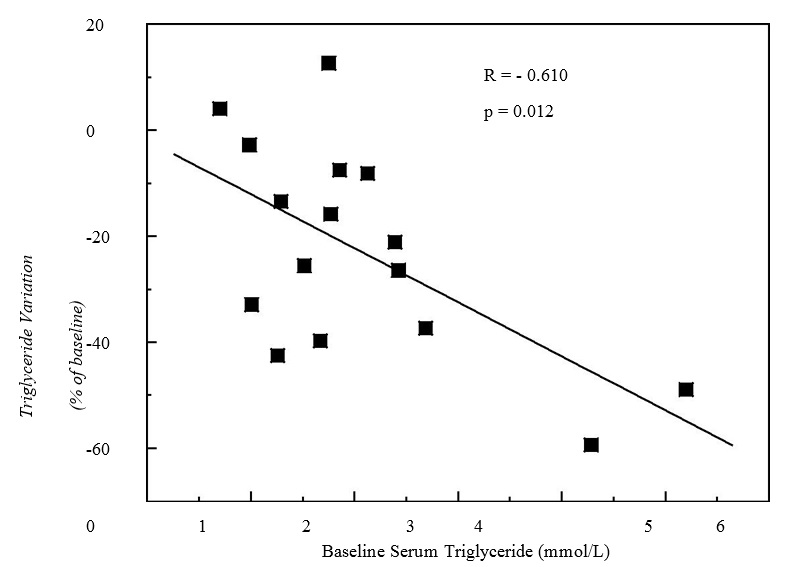

Laboratory data for serum analysis Two measurements of the serum biochemical parameters taken 30 days apart confirmed the stability of the parameters (coefficient of variations < 10%; data not shown) prior to the n-3 PUFA supplementation, as has been previously described for HF patients undergoing physical exercise training[23,35]. Compared to the baseline value (0 day), the n-3 PUFA supplementation promoted significant reductions in the triglyceride levels of 28.9% after 60 days of supplementation (Table 2). The decrease in triglyceride was dependent on the serum baseline levels of triglyceride. Figure 1 shows a slight, but significant, inverse correlation between the baseline triglyceride levels and the percentage of change due to n-3 PUFA supplementation (r = -0.60; p = 0.01; Pearson correlation). Moreover, the non-HDL-C fraction reduced by 9.0% (p < 0.05) after 60 days of supplementation. The sd-LDL-C levels decreased by 14.6% and 16.2% (p < 0.05) after 30 and 60 days of supplementation, respectively. We also observed a significant decrease of 20% in the relative amount of sd-LDL-C in relation to the total LDL-C (baseline: 74.4% vs. 30 or 60 days supplementation: 59.5%; p < 0.05) (Table 2). Considering the inflammatory parameters analyzed, only serum levels of TNF-α reduced significantly by 17.8% (p < 0.05) after 60 days of n-3 PUFA supplementation (Table 3).

Table 2: Serum lipid parameters of the heart failure patients before and after n -3 fatty acids supplementationa.

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | Study time | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 30 days | 60 days | |

| Total | 4.45 ± 0.80 | 4.52 ± 1.1(1.6%) | 4.23 ± 0.82(-4.9%) |

| HDL | 0.91 ± 0.16 | 0.94 ± 0.14(3.3%) | 0.92 ± 0.14(1.1%) |

| LDL | 2.66 ± 0.57 | 2.84 ± 0.84(6.8%) | 2.79 ± 0.65(4.9%) |

| sd-LDL | 1.98 ± 0.52 | 1.69 ± 0.78*(-14.6%) | 1.66 ± 0.67*(-16.2%) |

| Non-HDL | 3.54 ± 0.71 | 3.64 ± 1.05(2.2%) | 3.22 ± 0.76*(-9.0%) |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 2.04 ± 1.19 | 1.81 ± 1.18(-11.3%) | 1.45 ± 0.56*(-28.9%) |

aValues are means ± SD (n=16). Numbers in bracket represent variations in relation to baseline values.

*p < 0.05, compared with respective baseline values (paired Student's t-test).

Table 3: Serum inflammatory biomarkers of the heart failure patients before and after n-3 fatty acids supplementationaa.

| Study time | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 30 days | 60 days | |

| PCR-us (mg/L) | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.9(-15.3%) | 1.0 ± 1.0(-23.1%) |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 12.9 ± 7.1 | 11.7 ± 5.8(-9.8%) | 10.6 ± 6.7*(-17.8%) |

| IL-10 (pg/mL) | 4.8 ± 9.7 | 2.2 ± 0.9(-54.1%) | 4.5 ± 8.1(-6.2%) |

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | 1,76 ± 0.2 | 1.11 ± 0.2(-36.9%) | 0.74 ± 0.2(-57.9%) |

| IL-4 (pg/mL) | 1.91 ± 0.4 | 1.36 ± 0.4(-28.7%) | 1.53 ± 0.4(-19.8%) |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 3.71 ± 0.5 | 2.52 ± 0.5(-32.0%) | 2.81 ± 0.5(-24.2%) |

| VEGF (pg/mL) | 126.9 ± 62.1 | 128.2 ± 66.1(1.0%) | 128.3 ± 65.5(1.1%) |

aValues are means ± SD (n=16). Numbers in brackets represent variations in relation to baseline values. TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor alpha, us-PCR = ultrasensitivity C- reactive protein, IL = interleukin, VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor.

*p < 0.05, compared to respective baseline values (paired Student's t-test).

Figure 1: Pearson's correlation between variation in serum triglyceride concentration after 60 days of n-3 fatty acids supplementation and baseline serum triglyceride levels in heart failure subjects on physical exercise program (n = 16).

Lipid Transfer

After n-3 PUFA supplementation, 38.4% and 23.1% increases were seen in the transfer of CE from the lipidic nanoemulsion to HDL particles after 30 (p < 0.001) and 60 days (p < 0.05) of supplementation, respectively. The transfer of triglyceride, phospholipid and free cholesterol did not change, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Transfer of labeled lipids to HDL particle before and after n-3 fatty acids supplementation in heart failure patientsa

| Study time | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 30 days | 60 days | |

| 3H-CE (%) | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1** | 1.6 ± 0.1* |

| 14C-PL (%) | 22.2 ± 0.2 | 22.9 ± 0.3 | 22.1 ± 0.4 |

| 3H-TG (%) | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.2 ±0.2 |

| 14C- FC (%) | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.2 |

aValues are means ± SD (n=16). CE = Cholesteryl-ester, PL = Phospholipids, TG = Triglyceride, FC = Free cholesterol.

*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.001, compared with respective baseline values (paired Student's t- test).

Discussion

Dyslipidemia and low-grade inflammation are considered important predictors for the development of secondary events in patients with HF[1,3,4]. In the current intervention trial, we found that n-3 PUFA supplementation over 8 weeks significantly decreased the plasma levels of triglyceride, sd-LDL-C and TNF-α and increased the CE transfer to HDL in HF patients undertaking exercise training and statin therapy, whose plasma biochemical parameters were previously stable. Based on these results, we may accept the hypothesis that n-3 fatty acids supplementation improves the lipid metabolism and low-grade inflammation in HF patients undergoing complete medical treatment, i.e., pharmacological therapy and exercise training. However, it should be noted that the small number of participants, a relatively short duration of n-3 PUFA treatment and the absence of a control group due to the small number of volunteers might be considered as limitations of this study. Additionally, due to the small number of available patients these results cannot be extrapolated to the general population of HF patients and it may also be considered a limitation of this study.

The n-3 PUFA supplementation decreased the triglyceride values after 30 and 60 days. Furthermore, the baseline triglyceride levels were a partial, but significant, determinant of the response to n-3 PUFA supplementation. In HF patients with low baseline triglyceride values (average of 1 mmol/L), the n-3 PUFA supplementation had little effect in terms of the final triglyceride reduction (4.5%), while for HF subjects with elevated triglyceride values (average of 4.5 mmol/L) the same n-3 PUFA dose caused a much greater effect (average of 54.2% triglyceride reduction). These results are consistent with findings described by Balk et al[36] in other populations. It has been shown that physical exercise can improve the lipid parameters in HF patients through mechanisms which are not well defined[6]. In this study, it was not clear whether accumulated effects of exercise with n-3 PUFA supplement occurred or if specific biochemical mechanisms for the effects of n-3 PUFA were acting in HF patients undergoing exercise training and pharmacological therapy. Therefore, common n-3 PUFA mechanisms previously described elsewhere were considered to explain our findings. N-3 fatty acids may reduce serum triglyceride by modulating the nuclear receptors, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha and gamma (PPAR-α and PPAR-γ), and the sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1c, which control the expression of enzymes involved in the triglyceride metabolism, stimulating hepatic beta-oxidation and insulin sensitivity, and inhibiting the synthesis of lipids[37-39]. Other proposed mechanisms are the inhibition of the enzymes diacylglycerol acyltransferase and phosphohydrolases 1 and 2, resulting in reduced VLDL synthesis and secretion[38], and the elevation of triglyceride clearance from plasma through increased activity of lipase lipoprotein, explained in part by PPAR activation[39], transforming VLDL into larger, buoyant LDL particles, which are less atherogenic[40]. In the study reported herein we observed a significant reduction in the sd-LDL-C levels after 30 and 60 days of n-3 PUFA supplementation. This decrease was not accompanied by a reduction in LDL-C, which indicates an increase in the number of larger, buoyant LDL particles representing a shift to a less atherogenic pattern[41]. The mechanisms by which n-3 fatty acids modulate the LDL particle size are still unclear. Triglycerides are the main determinants of the LDL and HDL particle size, partly due to the exchange of triglyceride to CE mediated by the cholesteryl-ester transfer protein (CETP)[40-42]. In this regard, we speculate that reduced plasma levels of triglyceride due to n-3 PUFA supplementation provided low triglyceride transfer to LDL and HDL by CETP, thus decreasing the formation of LDL enriched with triglyceride and consequently the number of sd-LDL particles formed after triglyceride hydrolysis by hepatic lipase[42]. The decreased plasma triglyceride concentrations after n-3 PUFA supplementation may have also been responsible for the increased CE transfer to HDL. The transfer of CE to HDL via CETP is an essential metabolic step for reverse cholesterol transport in which cholesterol from peripheral tissues, including atherosclerotic lesions, is carried back to the liver and excreted in the bile[40,42]. Therefore, it can be proposed that as more CE is transferred to HDL particles more CE will be excreted by the liver. The absence of increased serum levels of HDL-C supports such an effective transfer of cholesterol from HDL to the liver. Overall, these results suggest that reverse cholesterol transport was improved by n-3 PUFA supplementation in HF patients undergoing exercise training and pharmacological therapy. Heart failure is also associated with high plasma levels of inflammatory mediators, such as eicosanoids and cytokines. These markers are involved in myocyte hypertrophy, apoptosis and ventricular remodeling, leading to HF[43]. In this study, the supplementation with n-3 PUFA significantly reduced the plasma concentrations of TNF-α by 19.5%. It has been previously shown that n-3 fatty acids are able to reduce the plasma concentrations of some cytokines, such as TFN-α in healthy and cardiac patients[44,45]. Although the mechanisms by which n-3 fatty acids affect cytokine synthesis are not well understood, it has been shown that n-3 fatty acids can inhibit the activity of the nuclear transcription factor kappa B (NF-κB), which regulates cytokine synthesis and is activated in HF patients[37,45,46]. In addition, PPAR-α and PPAR-β, which are activated by n-3 fatty acids, inhibited the NF-κB activation and mRNA expression of TNF-α[37].

It is noteworthy that, in this study, the subjects showed no significant variations in the intake of total calories and carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, saturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids (including n-3 PUFA) and fiber. This unchanged dietary profile and the fact that individuals were already adapted to physical exercise strengthen the hypothesis that the observed improvements in the lipid parameters and inflammatory markers were exclusively the result of n-3 PUFA supplementation.

Conclusion

In summary, in this clinical trial we demonstrated that n-3 PUFA supplementation in HF patients receiving exercise training and pharmacological treatment can promote beneficial effects by lowering the risk factors associated with secondary events in HF patients, such as hyperlipidemia, some inflammatory markers and lipid transfer. We suggest therefore the expansion of this study, with a higher number of participants and long-term intervention.

Acknowledgment

The fish oil capsules were kindly supplied by Nature's Bounty (Bohemia, NY, USA), and the study was supported by the Santa Catarina State Research Support Foundation (FAPESC – EFP 00004343), Santa Catarina, Brazil, and by the National Council for Research Development (CNPq), Brazil. F.S. Casagrande was the recipient of an MSc fellowship from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal e Ensino (CAPES). R.C. Maranhão received a Research Award from CNPq.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

CE: Cholesteryl-ester; CETP: Cholesteryl-ester transfer protein; CVD: Cardiovascular disease; DHA: docosahexaenoic acid; DGAT: diacylglycerol acyltransferase; EPA: eicosapentaenoic acid; FC: Free cholesterol; HDL: High-density lipoprotein; HF: Heart failure; IL: Interleukin; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein: sd-LDL: Small dense LDL; MCP-1: Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 n-3, Omega-3; PAP: Phosphohydrolases; PL: Phospholipid; PPAR: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; PUFA: Polyunsaturated fatty acids; SD: Standard deviation; SREBP-1c: Sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1c; TG: Triglyceride; TNF-α: Tumoral necrosis factor alpha: Us-CRP: Ultrasensitive C-reactive protein; VLDL: Very low density lipoprotein.

References

- 1. Bocchi, E.A., Marcondes-Braga, F.G., Bacal, F., et al. Update Brazilian Guidelines on Chronic Heart Failure - 2012. (2012) Arq Bras Cardiol 98(1Supp 1): 1- 33.

- 2. World Health Statistics 2008. WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

- 3. Piepoli, M.F., Conraads, V., Corrà, U., et al. Exercise training in heart failure: from theory to practice. A consensus document of the Heart Failure Association and the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. (2011) Eur J Heart Fail 13(4): 347- 357.

- 4. Goble, A. J., Worcester, M. U. C. Best Practice Guidelines for Cardiac Rehabilitation and Secondary Prevention. (1999) Department of Human Services: Victoria, Australia.

- 5. Kramsch, D.M., Aspen, A.J., Abramowitz, B.M., et al. Reduction of coronary atherosclerosis by moderate conditioning exercise in monkeys on an atherogenic diet. (1981) N Engl J Med 305(25): 1483- 1489.

- 6. Lavie, C.J., Thomas, R.J., Squires, R.W., et al. Exercise training and cardiac rehabilitation in primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. (2009) Mayo ClinProc 84(4): 373- 383.

- 7. Guimarães, G.V., Carvalho, V.O., Torlai, V., et al. Physical activity profile in heart failure patients from a Brazilian tertiary cardiology hospital. (2010) Cardiol J 17(2): 143- 145.

- 8. Dorosz, J. Updates in cardiac rehabilitation. (2009) Phys Med RehabilClin N Am 20(4): 719- 736.

- 9. Lee, J.H., Jarreau, T., Prasad, A., et al. Nutritional assessment in heart failure patients. (2011) Congest Heart Fail 17(4): 199- 203.

- 10. Leaf, D.A., Hatcher, L. The effect of lean fish consumption on triglyceride levels.(2009) PhysSportsmed 37(1): 37- 43.

- 11. Harris, W.S. Are n-3 fatty acids still cardioprotective? (2013) Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 16(2): 141- 149.

- 12. Lavie, C.J., Milani, R.V., Mehra, M.R., et al. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and cardiovascular diseases. (2009) J Am Coll Cardiol 54(7): 585- 594.

- 13. DiNicolantonio, J.J., Niazi, A.K., McCarty, M.F., et al. Omega-3s and cardiovascular health. (2014) Ochsner J 14(3): 399- 412.

- 14. Tavazzi, L., Tognoni, G., Franzosi, M.G., et al. Rationale and design of the GISSI heart failure trial: A large trial to assess the effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and rosuvastatin in symptomatic congestive heart failure. (2004) Eur J Heart Fail 6(5): 635- 641.

- 15. Dijkstra, S.C., Brouwer, I.A.,vanRooij,F.J., et al. Intake of very long chainn-3 fatty acids from fish and the incidence of heart failure: the Rotterdam Study. (2009) EurJ Heart Fail 11(10): 922- 928.

- 16. Mozaffarian, D., Bryson, C.L., Lemaitre, R.N., et al. Fish intake and risk of incident heart failure. (2005) J Am CollCardiol 45(12): 2015- 2021.

- 17. Yamagishi, K., Nettleton, J.A., Folsom, A.R. Plasma fatty acid composition and 479 incident heart failure in middle-aged adults: The Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study. (2008) Am Heart J 156(5): 965- 974.

- 18. Tavazzi, L., Maggioni, A.P., Marchioli, R., et al. Effect of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with chronic heart failure (the GISSI-HF trial): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. (2008) Lancet 372(9645): 1223- 1230.

- 19. Duda, M.K., O´Shea, K.M., Stanley, W.C. omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acidsupplementation for the treatment of heart failure: mechanisms and clinical potential. (2009) Cardiovasc Res 84(1): 33- 41.

- 20. Neschen, S., Morino, K., Rossbacher, J.C., et al. Fish oil regulates adiponectin secretion by a peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor-gamma-dependent mechanism in mice. (2006) Diabetes 55(4): 924- 928.

- 21. Itoh, M., Suganami, T., Satoh, N., et al. Increased adiponectin secretion by highly purified eicosapentaenoic acid in rodent models of obesity and human obese subjects. (2007) ArteriosclerThrombVascBiol 27(9): 1918- 1925.

- 22. Berg, A.H., Scherer, P.E. Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. (2005) Circ Res 96(9): 939-949.

- 23. McKelvie, R.S., Teo, K.K., McCartney, R.S., et al. Randomized controlled trial of exercise training in patients with congestive heart failure (EXERT). (1998) J Am Coll Cardiol 31(2s2): 1226- 1231.

- 24. Williams, J., Chair, C., Bristow, M.R., et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of heart failure. Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. (1995) Circulation 92: 2764- 2784.

- 25. Allain, C.C., Poon, L.S., Chan, C.S., et al. Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol. (1974) Clin Chem 20(4): 470- 475.

- 26. Bucolo, G., David, H. Quantitative determination of serum triglycerides by the useof enzymes. (1973) Clin Chem 19(5): 476- 482.

- 27. Sugiuchi, H., Uji, Y., Okabe, H., et al. Direct measurement of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in serum with polyethylene glycol-modified enzymes and sulfated α-cyclodextrin. (1995) Clin Chem 41(5): 717- 723.

- 28. Friedewald, W.T., Levy, R.I., Fredrickson, D.S. Estimation of concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of preparative ultracentrifugation. (1972) Clin Chem 18(6): 499- 502.

- 29. Sugiuchi, H., Irie, T., Uji, Y., et al. Homogeneous assay for measuring low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in serum with triblock copolymer and α-cyclodextrin sulfate. (1998) Clin Chem 44(3): 522- 531.

- 30. Codices, V., Martins, C., Novo, C., et al. Dynamics of cytokines and immunoglobulins serum profiles in primary and secondary Cryptosporidium parvum infection: Usefulness of Luminexx MAP technology. (2013) Exp Parasitol 133(1): 106- 113.

- 31. Rifai, N., Tracy, R.P., Ridker, P.M. Clinical efficacy of an automated high- sensitivity C-reactive protein assay. (1999) Clin Chem 45(12): 2136- 2141.

- 32. Hirano, T., Ito, Y., Saegusa, H., et al. A novel and simple method for quantification of small, dense LDL. (2003) J Lipid Res 44(11): 2193- 2201.

- 33. CavalcanteLda, S., da Silva, E. L. Application of a modified precipitation method for the measurement of small dense LDL-cholesterol (sd-LDL-C) in a population in southern Brazil. (2012) ClinChem Lab Med 50(9): 1649- 1656.

- 34. Lo Prete, A.C., Dina, C.H., Azevedo, C.H., et al. In vitro simultaneous transfer of lipids to HDL in coronary artery disease and in statin treatment. (2009) Lipids 44(10): 917- 924.

- 35. Belardinelli, R., Georgiou, D., Cianci, G., et al. Randomized, controlled trial of long-term moderate exercise training in chronic heart failure: Effects on functional capacity, quality of life and clinical outcome. (1999) Circulation 99(9): 1173- 1182.

- 36. Balk, E.M., Lichtenstein, A.H., Chung, M., et al. Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on serum markers of cardiovascular disease risk, a systematic review. (2006) Atherosclerosis 189(1): 19- 30.

- 37. Duda, M.K., O´Shea, K.M., Stanley, W.C. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for the treatment of heart failure: mechanisms and clinical potential. (2009) Cardiovasc Res 84(1): 33- 41.

- 38. Jacobson, T.A. Role of n-3 fatty acids in the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia and cardiovascular disease. (2008) Am J Clin Nutr 87(6): 1981S- 1990S.

- 39. Jacobson, T.A., Glickstein, S.B., Rowe, J. D., et al. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and others lipids: A review. (2012) J Clin Lipodol 6(1): 5- 18.

- 40. Bays, H.E. The role of CETP and the dyslipidemia found with the metabolic syndrome. (2004) Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2: 89- 105.

- 41. Kelley, D.S., Siegel, D., Vemuri, M., et al. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation improves fasting and postprandial lipid profiles in hypertriglyceridemic men. (2007) Am J Clin Nutr 86(2): 324- 333.

- 42. Rader, D.J., Hovingh, G.K. HDL and cardiovascular disease. (2014) Lancet 384(9943): 618- 625.

- 43. Adamopoulos, S., Parissis, J., Karatzas, D., et al. Physical training modulates proinflammatory cytokines and the soluble fats ligand system in patients with chronic heart failure. (2002) J Am Coll Cardiol 39(4): 653- 663.

- 44. Dangardt, F., Osika, W., Chen, Y., et al. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation improves vascular function and reduces inflammation in obese adolescents. (2010) Atherosclerosis 212(2): 580- 585.

- 45. Bloomer, R.J., Larson, D.E., Fisher-Wellman, K.H., et al. Effect of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid on resting and exercise- induced inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers: a randomized, placebo controlled, cross-over study. (2009) Lipids Health Dis 8: 36.

- 46. Zhao, Y.T., Shao, L., Teng, L.L., et al. Effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid therapy on plasma inflammatory markers and N- terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in elderly patients with chronic heart failure. (2009) J Int Med Res 37: 1831- 1841.