Polar Bioactive Constituents from Aerial Parts of Thymus longicaulis C. Presl

Monica Scognamiglio2, Vittoria Graziani1, Antonio Fiorentino1

Affiliation

- 1Department of Environmental Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Technologies, Second University of Naples, Italy

- 2Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, Hans-Knöll-Straße, Germany

Corresponding Author

Brigida, D’Abrosca, Department of Environmental Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Technologies, Second University of Naples, Via Vivaldi 43, Caserta, Italy; Tel: +39-0823-274605; E-mail: brigida.dabrosca@unina2.it

Citation

D’Abrosca, B., et al. Polar Bioactive Constituents from Aerial Parts of Thymus Longicaulis C. Presl. (2016) Lett Health Biol Sci 1(1): 1- 4.

Copy rights

© 2016 D’Abrosca, B. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Thymus longicaulis C; Aromatic perennial herb; Bioactive Constituents

Abstract

Thymus longicaulis C. Presl., belonging to the Lamiaceae family, is a small aromatic perennial herb typical of the Mediterranean vegetation. This species, known in traditional phytoteraphy of Italy, has been extensively investigated in terms of chemical analysis and biological activity of its essential oils. Nevertheless, few data are available in the literature, regarding the chemical characterization of polar components of T. longicaulis. In this study, the phytochemical investigation of methanol extract of T. longicaulis through different chromatographic techniques, led to the isolation of thirteen compounds. The structures of rosmarinic acid and two derivatives, as well as that of flavones, triterpenes and a lignan have been elucidated on the basis of extensive NMR spectroscopic analyses. The evaluation of DPPH radical scavenging activity of pure compounds has been performed.

Introduction

Plants are a rich source of bioactive compounds, characterized by a wide range of pharmacological activities, can be used for different applications such as health promoting ingredients, nutraceuticals, and food additives in formulations of functional foods[1]. Although fresh and dried aromatic plants, due to their richness in volatile components, have been used as flavorings since ancient times, they produce a large amount of other secondary metabolites (e.g. flavonoids, phenolic acids, saponins), responsible for several beneficial effects on human health. By virtue of their properties, during the last few decades, they have also become a subject for a search of natural antioxidants[2]. In particular, flavonoids and phenolic acids play an important role in protecting organisms against dangerous effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS). So recently, there has been a great interest towards the therapeutic potentials of aromatic plants as antioxidant in reducing free radical induced tissue damage and their use as antioxidant in food and drugs[3].

The genus Thymus, belonging to the Lamiaceae family, is one of the most critical genera of the Mediterranean flora. This genus comprises about 400 species of perennial aromatic herbaceous plants one of them is Thymus longicaulis (C. Presl). T. longicaulis is a species with long, somewhat woody, creeping branches, with a terminal inflorescence[4]. This species, known in traditional phytoteraphy of South and Central Italy, is used as a tonic as against cough and influence[5].

Recently, chemical composition and different biological properties of essential oils of T. longicaulis have been investigated: antimicrobial activity of T. longicaulis essential oil from Croatia[6], antioxidant properties of essential oil of T. longicaulis from Turkey[7].

Few reports[8] are available regarding the chemical characterization of poly- phenolic components of T. longicaulis. In the investigation of in this framework, the aim of this study is the phytochemical investigation of the polar extract of T. longicaulis as well as the evaluation of DPPH radical scavenging activity of the isolated compounds.

Materials and Methods

General experiment procedures

NMR spectra were recorded at 300.03 MHz for 1H and 75.45 MHz for 13C on a Varian Mercury 300 spectrometer Fourier transform NMR in CD3OD or CDCl3 solutions at 25°C. Chemical shifts are reported in δ (ppm) and referenced to the residual solvent signal, J (coupling constant) are given in Hz. Standard pulse sequences and phase cycling from Varian library were used for 1H,13C, DEPT, DQF-COSY, COSY, TOCSY, HSQC, H2BC, HMBC and CIGAR–HMBC experiments. 1H NMR spectra were acquired over a spectral window from 14 to 2 ppm, with 1.0 s relaxation delay, 1.70 s acquisition time (AQ), 90° pulse width = 13.8 μs. The initial matrix was zero-filled to 64 K. 13C- NMR spectra were recorded in 1H broadband decoupling mode, over a spectral window from 235 to 15 ppm, 1.5 s relaxation delay, 90° pulse width = 9.50 μs, AQ = 0.9 s. The number of scans for both 1H and 13C-NMR experiments was chosen depending on the concentration of the samples. Also for homonuclear and heteronuclear 2D-NMR experiments, data points, number of scan and of increments were adjusted according to the sample concentrations. Correlation spectroscopy (COSY) and double quantum filtered COSY (DQF-COSY) spectra were recorded with gradient enhanced sequence at spectral widths of 3000 Hz in both f2 and f1 domains; the relaxation delays were of 1.0s. The total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) experiments were performed in the phase-sensitive mode with a mixing time of 90 ms. The spectral width was 3000 Hz. Nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) experiments were performed in the phase-sensitive mode. The mixing time was 500 ms and the spectral width was 3000 Hz. For all the homonuclear experiments, the initial matrix of 512 x 512 data points was zero-filled to give a final matrix of 1 k x 1 k points. Proton- detected heteronuclear correlations were measured.

Heteronuclear single-quantum coherence (HSQC) experiments (optimized for 1J (H,C) = 140 Hz) were performed in the phase sensitive mode with field gradient; the spectral width was 12,000 Hz in f1 (13C) and 3000 Hz in f2 (1H) and 1.0 s of relaxation delay; the matrix of 1 k x 1 k data points was zero-filled to give a final matrix of 2 k x 2 k points. Heteronuclear 2 bond correlation (H2BC) spectra were obtained with T = 30.0 ms, and a relaxation delay of 1.0 s; the third-order low-pass filter was set for 130 < 1J(C,H) < 165 Hz. Heteronuclear multiple bond coherence (HMBC) experiment (optimized for nJ (H,C) = 8 Hz) was performed in the absolute value mode with field gradient; typically, 1 >H–13C gHMBC were acquired with spectral width of 18,000 Hz in f1 (13C) and 3000 Hz in f2 (1H) and 1.0 s of relaxation delay; the matrix of 1 k x 1 k data points was zero-filled to give a final matrix of 4 k x 4 k points. Constant time inverse-detection gradient accordion rescaled heteronuclear multiple bond correlation spectroscopy (CIGAR–HMBC) spectra (8 > nJ (H,C) > 5) were acquired with the same spectral width used for HMBC. Heteronuclear single-quantum coherence– total correlation spectroscopy (HSQC-TOCSY) experiments were optimize for nJ (H,C) = 8 Hz, with a mixing time of 90 ms.

Analytical TLC was performed on Merck Kieselgel 60 F254 or RP-8 F254 plates with 0.2 mm layer thickness. Spots were visualized by UV light or by spraying with H2SO4/AcOH/H2O (1:20:4). The plates were then heated for 5 min at 110°C. Preparative TLC was performed on Merck Kieselgel 60 F254 plates, with 0.5 or 1.0 mm film thickness. Column chromatography (CC) was performed on Merck Kieselgel 60 (70 – 240 μm), Merck Kieselgel 60 (40 – 63 μm), Bakerbond C8 and C18 Sephadex LH-20, Amberlite XAD-4.

Plant material

Thymus longicaulis C. Presl was collected in a garrigue on the calcareous hills of Durazzano, (41°3′N, 14°27′E; southern Italy) in the vegetative state and identified by Dr. Assunta Esposito of the Dept. of Environmental, Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Technologies of Second University of Naples (SUN). A voucher specimen (CE235) has been deposited at the Herbarium of the Department. Leaves of Thymus longicaulis were harvested and immediately frozen in liquid N2 in order to avoid unwanted enzymatic reactions and stored at −80°C up to the freeze drying process. Once freeze dried they were powdered in liquid nitrogen and stored at −20°C until the extraction process was carried out.

Extraction and isolation of compounds

Dried leaf material was powdered and extracted by ultrasound assisted extraction (Elma® Transonic Digitals) one hour with methanol. The extract was filtered on Whatman paper and concentrated under vacuum. After removal of the solvent, a dried crude extract was obtained (4.1 g) which was stored at -20°C until its purification. The methanol extract, dissolved in distilled water and shaken with EtOAc, give an aqueous and an organic fraction.

The first was chromatographed on Amberlite XAD-4 and eluted first with water, to eliminate sugars, peptides, free amino acids and other primary metabolites, and then with methanol. The alcoholic eluate furnished 1.1g of residual material which was chromatographed on Sephadex LH- 20 eluting with MeOH/H2O polarity decreasing solutions and collecting six fractions (A-F). Fraction A, re-chromatographed by SiO2-flash CC, eluting with the organic phase of a biphasic solution constituted by CHCl3/MeOH/H2O (13:7:4), furnished pure compound 1 (7.7 mg) and another fraction that, purified by TLC [SiO2, lower phase of CHCl3/MeOH/H2O (13:7:4)] gave compounds 2 (1.2 mg) and 13 (1.6 mg).

Fraction B, was chromatographed by RP-18 CC furnishing two fractions: fraction B1 contained pure 6 (20.1 mg), while B2 gave pure compound 7 (4.5 mg). Fraction C contained pure compound 4 (89 mg), fraction D, instead, re-chromatographed by RP-18 CC furnished a fraction identified as compound 9 (10.9 mg). Fraction E was purified by SiO2 TLC (0.5 mm), eluting with the lower phase of the biphasic solution CHCl3/MeOH/0,1% TFA (13:7:2), and gave two spots. The first spot was identified as pure 11 (2.8 mg), while the second spot as the metabolite 10 (1.5 mg). Finally, fraction F after re-chromatography on RP-18 CC (MeOH: H2O polarity decreasing solutions) furnished a fraction identified as compound 12 (4.5 mg).

The organic fraction of methanol extract, chromatographed on Sephadex LH-20 eluting with hexane/MeOH/CHCl3 (2:1:1) solution, furnished three fractions G1-G3. The first re-chromatographed by SiO2-flash CC, eluting with decreasing polarity of CHCl3/MeOH solutions, furnished pure compound 4 (33.3 mg).

Fraction G2, purified by SiO2-flash CC, eluting with decreasing polarity of CHCl3/ EtOAc solution, gave a fraction identified as compound 3 (6.6 mg). Finally, fraction G3 was purified by TLC, SiO2 CHCl3/MeOH (4:1) to obtain pure 8 (1.2 mg).

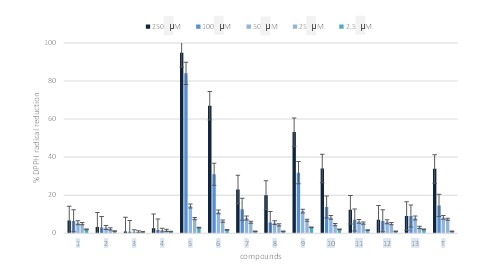

Radical scavenging capacity

In order to assess the antioxidant efficacy of the isolated pure metabolites from T. longicaulis leaves, the 2, 2-diphenyl- 1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) spectrophotometric method was performed as previously reported[9]. Increasing concentrations of pure metabolites were tested (5, 25, 50, 100 and 250 μM). All the tests and analyses were carried out in triplicate. Trolox® (6-hydroxy-2, 5, 7, 8-tetrametmethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid), a water soluble vitamin E analogue, was used as a positive control.

Results and Discussion

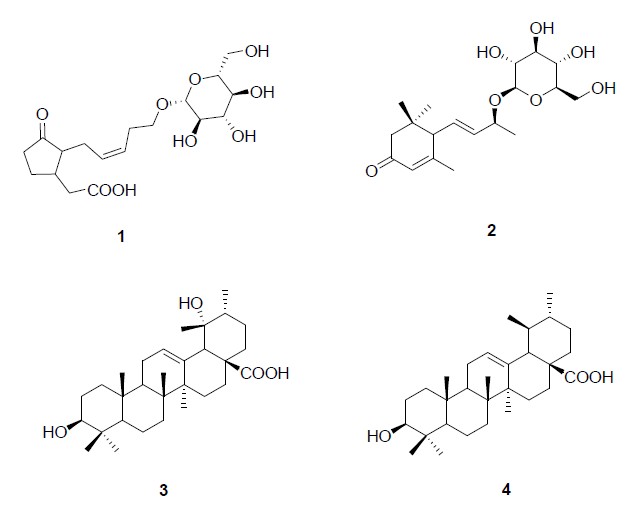

The phytochemical investigation of the methanol extracts of thyme led to isolation and characterization of thirty compounds (figures 1 and 2) belonging to different classes of secondary metabolites: isoprenoids, cinnamic acid derivatives, and flavones. In particular compounds 1 and 2 were identified as tuberonic acid 13-O-β-D-glucopyranoside and 4, 7-megastigmadien- 3-one 9-O-β- D-glucopyranoside, respectively, both isolated from seeds of Astragalus complanatus[10].

Figure 1: Chemical structures of terpenoids (1- 4) isolated from Thymus longicaulis.

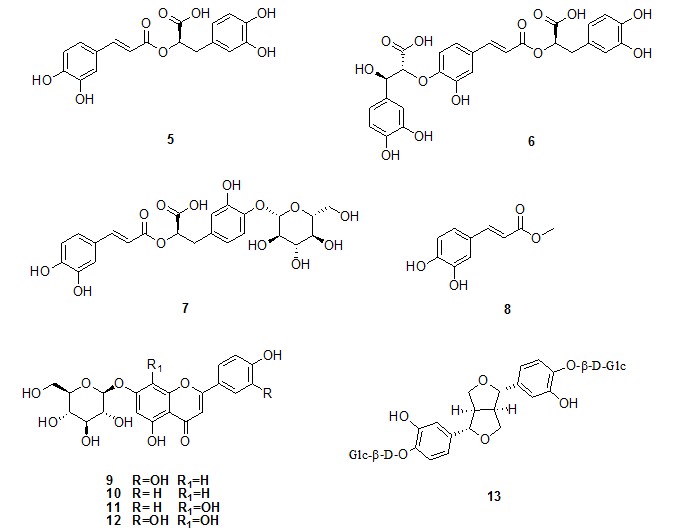

Figure 2: Chemical structures of caffeic acid derivatives (5-8), flavones (9-12), and lignan (13) isolated from Thymus longicaulis

Metabolites 3 and 4 are two ursane triterpenes. In particular, 3 was identified as 3β-hydroxy-urs-12- en-28-oic acid, known as ursolic acid, while compound 4 has been characterized as pomolic acid, by comparison of its spectral data with those reported in literature data. Both triterpenes were as reported as constituent of Annurca apple fruits[11]. Metabolites 5-7 were identified as caffeic acid derivatives (figure 2); in particular, compound 5 was recently reported as constituent of several aromatic Mediterranean plant species[8]. Compound 6 was elucidated as salvianolic acid K, previously isolated from Salvia deserta[12].

NMR data of 7, known as 4-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl rosmarinic acid, was in good accordance with[13], that reported this compound as constituent of Sanicula lamelligera while metabolite 8 was identified as methyl caffeoate.

Compounds 9-12 were identified as flavone derivatives (figure 2). Compound 9 was previously isolated from aerial parts of Teucrium polium[14], while luteolin-7-O-β-D- glucopyranoside, known as cynaroside (10), was already reported as constituent of Marrubium globosum ssp. libanoticum[15].

Flavone 11 was characterized as isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, by comparision of its spectral data with those reported in literature data[16]. Compound 12 was identified as gossipytrin first isolated from Papaver nudicaule[17].

Finally, compound 13 identified as (+)-pinoresinol 4, 4′-O-bis-β-D-glucopyranoside was reported from constituent of Clematis stans roots[18].

In order to evaluate the antioxidant efficacy of the isolated pure metabolites from T. longicaulis leaves, the 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) spectrophotometric method was performed as previously reported using five decreasing concentrations of pure metabolites. The results are reported in (figure 3). The polyophenols showed the highest radical scavenging activity. In particular rosmarinic acid (5) and salvialonic acid (6) reducing DPPH concentration of 94 % and 67 %, respectively at highest concentration, with considerable radical scavenging activity also at 100 μM.

Figure 3: DPPH radical scavenging activity of compounds isolated from Thymus longicaulis.

Rosmarinic acid is distributed in 26 plant families, and its biological activity has been extensively examined. Earlier studies ascribed to rosmarinic acid antiviral, antibacterial, anti-inflammaroty and antioxidant properties[19]. Recently, others interesting biological effects of rosmarinic acid have been reported: antifibrotic activity, protection of neurons against insults, suppression of UVB-induced alterations to human keratinocytes, inhibition of bone metastasis from breast carcinoma[20].

Salvianolic acid K is reported in the literature for its antioxidant[21] and aldose reductase inhibitory activities[22].

Among flavones, cynaroside (luteolin-7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside) prevents H2O2-induced apoptosis in H9c2[23] and SH-SY5Y[24] cell lines by reducing the endogenous production of ROS. Furtheremore, cynaroside is very effective against Gram-negative bacteria[25] and showed significant antipsoriatic activity using photodermatitis model[26].

Isocsutellarein derivatives have also been described for its important beneficial activities: antioxidant[27] antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory[28] and significant inhibitory activity against osteoclast differentiation[29].

Spices are widely investigated for their essential oils content in term of chemical composition and biological activity. Nevertheless, spices are also abundant sources of polyphenols which have interesting biological properties as recently reported also by Kindl, et al (2015)[30] that report antioxidant and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activities of the ethanolic extracts of six selected Thymus species growing in Croatia. Consumption of spices has been implicated in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases, carcinogenesis, and inflammation mainly due to the presence of polyphenols.

References

- 1. Meskin, M.S., Bidlack, W.R., Davies, A.J., et al. Phytochemicals in Nutrition and Health. (2002) CRC Press.

- 2. Hossain, M.B., Brunton, N.P., Barry-Ryan, C., et al. Antioxidant activity of spice extract and phenolics in comparison to synthetic antioxidants. (2008) Rasayan J Chem 1(4): 751-756.

- 3. Saxena, M., Saxena, J., Pradhan, A. Flavonoids and phenolic acids as antioxidant in plants and human health. (2012) Int J Pharm Sci 16(2): 130-134.

- 4. De-Martino, L., Bruno, M., Formisano, C., et al. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oils from two species of Thymus growing wild in southern Italy. (2009) Molecules 14(11): 4614-4624.

- 5. Scherrer, A.M., Motti, R., Weckerle, C.S. Traditional plant use in the areas of Monte Vesole and Ascea, Cilento National Park (Campania, Southern Italy). (2005) J Ethnopharmacol 97(1): 129-143.

- 6. Vladimir-Kne