Protective effect of Lyciumbarbarum extract as Antioxidant Agent on Roridin A Induced Hepatotoxicity in Male Rat

Nagwa M. Elsawi1*, Madeha N. Alseeni2, Hala I. Madkour3, Doha S Mohamed4, Asma. S.Abdo1

Affiliation

- 1Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Sohag University, Sohag, Egypt

- 2Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, King Abdel-Aziz University, Jaddah, Saudi Arabia

- 3Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Sohag University, Sohag, Egypt

- 4Department of Histology, Faculty of Medicine, Sohag University, Sohag, Egypt

Corresponding Author

Nagwa M. Elsawi, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Sohag University, Sohag, Egypt. E-mail: elsawinagwa@yahoo.com

Citation

Elsawi, N. M. et al. Protective Effect of Lycium Barbarum Extract as Antioxidant Agent on Roridin A: Induced Hepatotoxicity in Male Rat. (2015) J Food Nutr Sci 2(2): 81-85.

Copy rights

©2015 Elsawi, N. M.. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Abstract

The fruit goji berry of Lyciumbarbarym, a traditional Chinese herbal medicine, has been widely used in healthy diets due to its potential role in the prevention of chronic diseases. We studied the effects ofroridin A toxin in male rat liver and their amelioration by goji extract. Thirtymale adult albino rats were divided into three groups (10 rats each). Group 1 (Control group) was given only the solvent(DMSO) of roridin A. Group 2 was administered a single dose (0.6 mg/kg) of rordin A mycotoxin (dissolved in 1% DMSO) for one week. Group 3 was treated prophylactically with goji extract (5 mg/kg) using gastric tube daily for 6 days and left for one week. Roridin A showed a highly significant increase in serum levels of cholesterol, triglycerides and significant increase inglucose, total antioxidants and tumor necrosis factor (TNF). There was significant decrease in serum ferritin level. On the other hand, administration of goji along with rordin A showed a reduction in the above mentioned factors and elevation inferritin level. Histopathological changes in the rat liver coincided with the above biochemical changes. In conclusion; the treatment of rats with goji extract ameliorated the adverse effects of rordin A. Thus, gojimay be used asan antioxidant for certain toxins.

Introduction

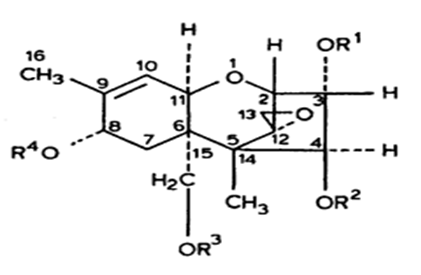

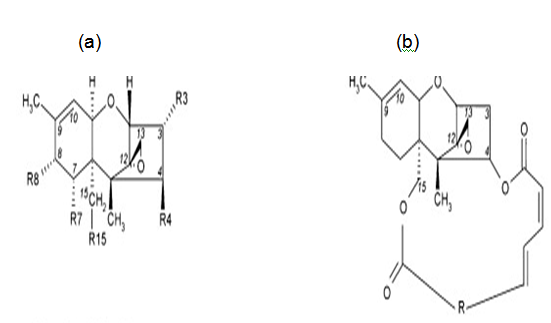

Mycotoxins, by-products of fungal metabolism have been implicated as causative agents of adversehealth effects in humans and animals that have consumed fungus-infected agricultural products[1,2]. The trichothecenes are very large family of chemically related toxins produced by various species of Fusarium, Myrotecium, Trichoderma Cephalosporium, Verticimonosporium and Stachybotrys[3]. Trichothecenes occur worldwide in a wide variety of food and other commodities. They are often found in cereal grains, especially in the temperate regions of America, Asia and Europe[4,5]. This family of mycotoxins causes multi-organ effects including emesis, diarrhea, weight loss, nervous disorders, cardiovascular alterations, immunosuppression, hemostatic derangements, skin toxicity, decreased reproductive capacityand bone marrow damage[3,6]. All trichothecenes have in common a 9, 10 double bond and a 12, 13 epoxide group[7], which are responsible for their toxicological activity[8] but, extensive variation exists relative to ring oxygenation patterns[7] (Figure 1.1). Previously, trichothecenesmycotoxins were conveniently divided into two structure types: (1) Simple, e.g., T-2 toxin, diacetoxyscirpenol (DAS), verrucarol, DON, etc.; and (2) Macrocyclic, e.g., verrucarin A, B, J androridin A, D, E, etc. (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1: Structure of Trichothecenemycotoxin

Figure 1.2: Structure of (a) simple and (b) macrocyclictrichothecenes

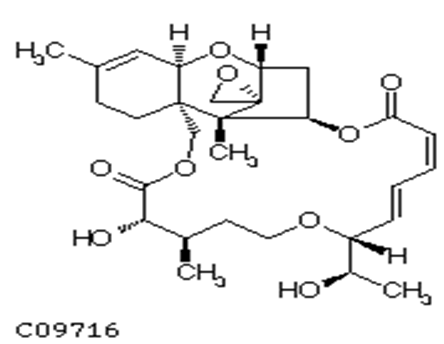

One of the most important macrocyclic-trichothecenes is roridin A(Figure 1.3), mycotoxin of this study, which is produced by Myrotheciumverrucaria, Myrotheciumroridum, Myrotheciumleucotrichium and Dendrodochiumtoxicum[9-11].

Figure 1.3: Structure of Roridin A

Goji berry (Figure 2) species are deciduous woody perennial plants which are grown in the northwestern part of China, primarily in the Ningxia HuiAutonomous Region. Goji berry is prized for its versatility of colorand nut-like taste in common meals, snacks, beverages, and medicinal applications[12]. It has been widelyused as a functional ingredient in nutraceuticals since excessive studies havedemonstrated that goji berry plays a crucial role in the improvement of vision, prevention of aging andage-related diseases, inhibition of cancer development and boosting immune system[13,14].

Figure 2: Goji berry fruit

The present study was planned to assess the biochemical profile supported by histological evidence of single dose of roridin Aonliver of male rat in order to evaluate the possible role of goji extract in reversing roridin A toxicity.

Materials and Methods

Animals: Male adult albino rats weighing 150-200 grams at the age of 3.0- 4.0 months were used. Animals were obtained from the animal house, Faculty of Medicine, Assiut University and were housed in animal place with room temperature being maintained at 25 ± 2°C. Animals were fed on a commercial pellet diet and kept under normal light/dark cycle. Animals were given food and water ad libitum.

Chemicals and Solutions Preparation: Gojidried fruits were collected from china market. Roridin A,from a Myrothecium species was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Solvent 1% DMSO (0.6 mg/kg) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Kits were procured from Biovision, USA. The animals were randomly divided into 3 groups each group comprised 10 rats. The animals were treated as follows:

Group 1: Solvent 1% DMSO saline solution (0.6 mg/kg) for one week.

Group 2: Rordin Asingle dose (0.6 mg/kg) dissolved in 1% DMSO for one week[15].

Group 3: Goji extract (5.0 mg/kg)[16] using gastric tube for 6 days daily then the animals treated with roridin A and left for one week.

After 2 weeks of injectionall the rats were anesthetized using ether. Blood samples were collected from the heart and serum was separated by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes and stored at -20°C until analysis. Serum samples were analyzed for glucose[17]; total cholesterol and triglyceride[18,19]. Total antioxidants (TAS) was measured according to Miller, et al.[20], and ferritin was measured according to Young[21]. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) was determined according to the method of Beutler and Ceramic[22].

Histological Examination

Rats were killed and the abdomen was opened. The liver was excised and washed in sterile saline solution. The tissues were fixed in neutral buffered formalin, processed to paraffin wax sectioned at 5 μm. The slides were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Stained sections were examined and photographed using digital camera, attached to Olympus CX21 light microscope and connected to computer.

Statistics

Statistics was performed using the statistical graph pad prism 5. One way analysis of variables (ANOVA) was used. Significant differences between the groups was determined using a post-hoc Newman-keuls test. All the results are expressed as mean ± SE and the level of significance between groups were considered significant (*) at p < 0.05 and highly significant (**) at p < 0.001.

Results and Discussion

Histological Results

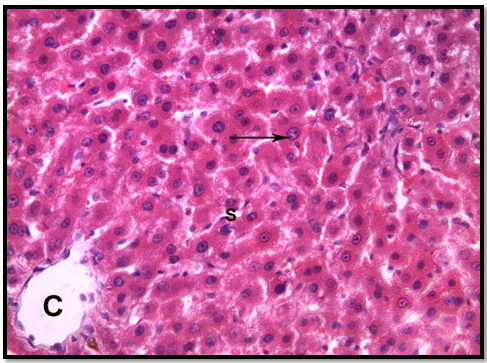

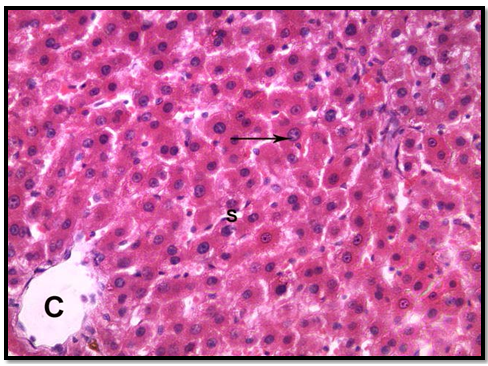

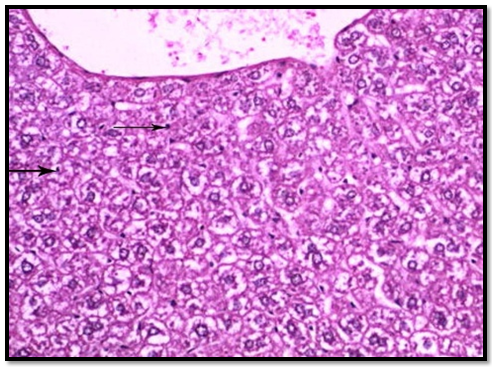

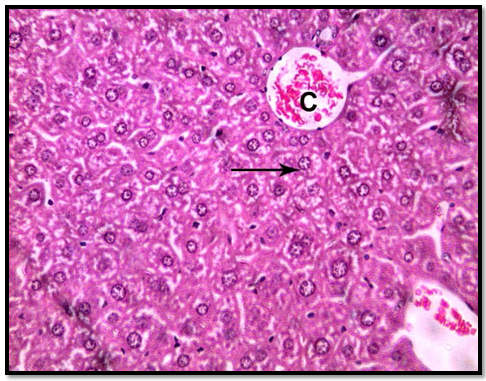

In group 1 (control group), normal hepatic lobular pattern with cords of hepatocytes appeared radiating from the central vein. These cords were separate by blood sinusoids. The hepatocytes were polygonalacidophilic cells with vesicular nucleus (Figure 3). In group 2 treated with roridin A, the central vein appeared markedly dilated and congested. Most of the cells were highly vacuolated with pyknotic deeply stained nuclei (Figures 4 and 5). These changes indicatedproliferation of organelles such as smooth endoplasmic reticulum, peroxisomes and mitochondria involved in detoxification processes[23]. In group 3 treated prophylactically with goji extract the central vein appeared lessdilated and congestedas compared to the group 2. Most of the cells were less vacuolated with vesicular nuclei more or less similar to the control group (Figure 6). Goji extract was found to offer some protection against roridin A hepatotoxicity. The protection appeared in the form of improvement of histological changes where hepatocyte looked more or less similar to control.

Figure 3: A section of control liver showing the central vein (c ),cords of hepatocyte separated from each other by blood sinusoids(S),hepatocytes are polygonal acidophilic with vesicular nucleus (arrow)(H& E x 400)

Figure 4: A section of liver showing congested dilated central vein (c ) ,most of hepatocytes are highly vacuolated with pyknotic deeply stained nuclei (arrow) ( group 2) (H& E x 200)

Figure 5: A magnified image of the previous section showing, most of hepatocytes are highly vacuolated with pyknotic deeply stained nuclei (arrow) (H& E x 400)

Figure 6: A section of liver showing, most hepatocytes are less vacuolated compared to the previous group most of the nuclei are vesicular (arrow) (H& E x 400)

Biochemical Parameters

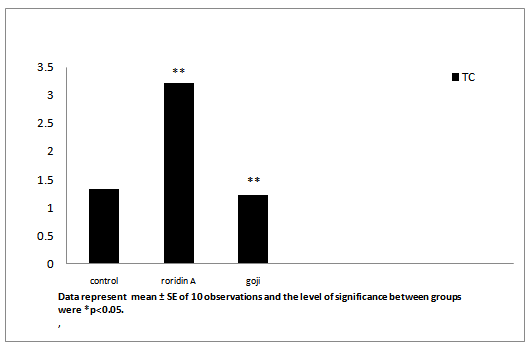

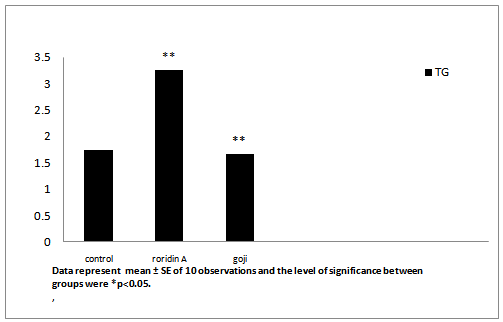

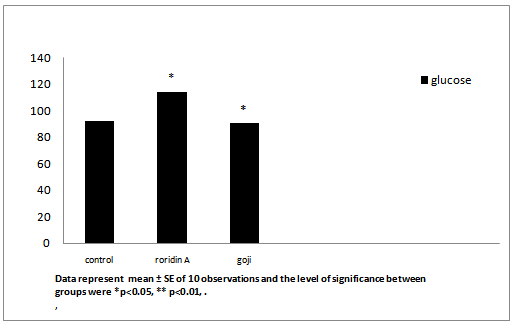

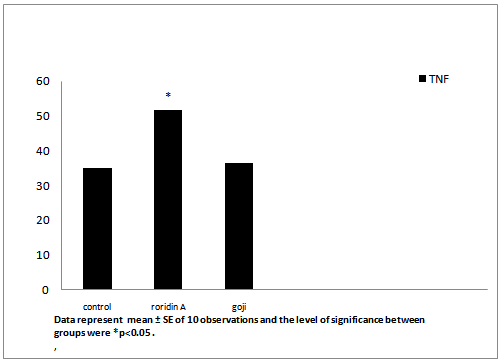

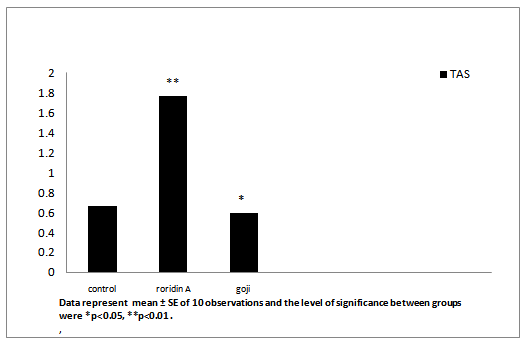

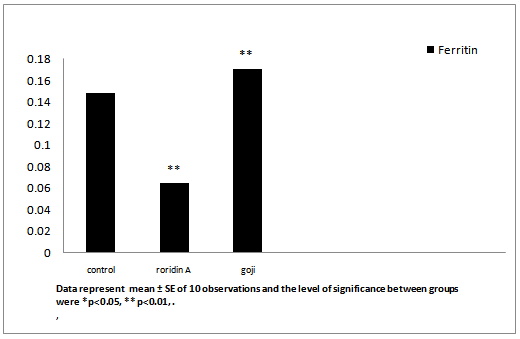

After administration of roridin A mycotoxin there was a highly significant increase in cholesterol, triglyceride and total antioxidants (Table 1, Figures 7, 8 and 11). The results showed significant increase in glucose and TNF levels (Figures 9 and 10). There was ahighly significant decrease in ferritin observed over a period of one week (Figure 12). These results may be attributed to the varying toxic effect ofrordin A. The above data are in agreement with the results obtained by Ueno[24] who reported thatall trichothecenes have in common a 9, 10 double bond and a 12, 13 epoxide group[7] which areresponsible for their toxicological activity[8]. It also prevents polypeptide chain initiation or elongation by interaction with eukaryotic 60 S mammalian ribosomal subunitand interaction with the enzyme peptidyl-transferase. That leads to varying degrees of inhibition of peptide bond formation[7].

Table 1.Effect of roridin A (0.6 mg/kg) alone and with goji extract (5.0 mg/kg) on some biochemical parameters in male rats.

| Biochemical parameters | Control (Group 1) | Roirdin (Group 2) | Goji extract (Group 3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 1.32 ± 0.001 | 3.21 ± 0.005** | 1.20 ± 0.01** |

| TG (mg/dl) | 1.758 ± 0.003 | 3.255 ± 0.011** | 1.65 ± 0.004** |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 92.63 ± 0.21 | 114.3 ± 0.080* | 90.62 ± 0.22* |

| Total antioxidant (mmol/L) | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.27 ± 0.02** | 0.37 ± 0.02* |

| TNF pg/ml | 35.04 ± 0.012 | 51.74 ± 0.4* | 36.4 ± 0.2 |

| Feritin (μg/ml | 0.18 ± 0.004 | 0.06 ± 0.001** | 0.17 ± 0.001** |

Data represent mean ± SE of 10 observations. Level of significance between groups at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

Figure 7: Effect of roridin A (0.6 mg/kg) alone and with goji extract (5.0 mg/kg) on cholesterol in rats

Data represent mean ± SE of 10 observations and the level of significance between groups were *p < 0.05.

Figure 8: Effect of roridin A (0.6 mg/kg) alone and with goji extract (5.0 mg/kg) on TG in rats

Data represent mean ± SE of 10 observations and the level of significance between groups were *p < 0.05.

Figure 9: Effect of roridin A (0.6 mg/kg) alone and with goji extract (5.0 mg/kg) on glucose in rats

Data represent mean ± SE of 10 observations and the level of significance between groups were *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Figure 10: Effect of roridin A (0.6 mg/kg) alone and with goji extract (5.0 mg/kg) on TNF in rats

Data represent mean ± SE of 10 observations and the level of significance between groups were *p < 0.05 .

Figure 11: Effect of roridin A (0.6 mg/kg) alone and with goji extract (5.0 mg/kg) on TAS in rats

Data represent mean ± SE of 10 observations and the level of significance between groups were *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 .

Figure 12: Effect of roridin A (0.6 mg/kg) alone and with goji extract (5.0 mg/kg) on ferritin in rats

Data represent mean ± SE of 10 observations and the level of significance between groups were *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

On the other hand, male rats treated prophylactically with goji extract showed highly significant decrease incholesterol, triglycerideand significant decrease in glucose (Table 1 and Figures 7-9). These results are in agreement with the previous research[25]. The hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of Lycium barbarumwere investigated through designed sequential trials and by measuring blood glucose and serum lipid parameters in alloxan-induced diabetic or hyperlipidemic rabbits[25]. Also, Preethi et al.,[26] evaluated hypolipidemic effects of Lyciumbarbarum and reported results similar to the findings of the present study. Lyciumbarbarum contains pharmacologically active constituents that offer a variety of indications that affect different organs of the body[27]. Both poly-saccharides and vitamin antioxidants from Lyciumbarbarum fruits were possible active principles of hypolipidemic effect[28]. Hepatic genes expression profiles demonstrated that Lyciumbarbarum polysaccharide can activate the phosphorylation of adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase, suppress nuclear expression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c, and decrease protein and mRNA expression of lipogenic genes in vivo or in vitro[28].

In the present study, the total antioxidant increased in roridin a groupcompared to the control. In goji extract treated group total antioxidant was elevated as compared to control (Table 1 and Figure 11). High level of TAS in roridin a treated group may reflect a body defense against oxidative toxicants[29]. Normally, one would expect a decrease in the antioxidant levels after the administration of a drug that can be potentially hepatotoxic. On the contrary in the present study, it was interesting to find a significant increase in TAS in roridin a treated rats, when liver damage was minimal. It is suggested that increase in antioxidant level may be a defense mechanism in the liver to prevent roridin A toxicity. In fact this view is supported by Abraham and Sugumar[30], who demonstrated a significant increase in glutathione and antioxidant enzymes. Lyciumbarbarum was effective in reducing necro-inflammation and oxidative stress induced by a chemical toxin[31]. Lyciumbarbarum increasedsuperoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidaseand glutathione reductaseactivities, thereby inhibiting oxidative stress-induced damage. Lyciumbarbarum ameliorates oxidative stress-induced cellular apoptosis[32].

In roridin A treated group, there was a significant increase in TNF thatameliorated after the administration of goji in male rats (Table 1 and Figure 10). Lyciumbarbarum inhibited polymorphonuclear neutrophil accumulation and ameliorated changes in the TNF level in intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injuries in rats[33].

Ferritin dependent oxidative damage, may be involved in the pathogenesis of disease where increased total antioxidants (enzymatic or non-enzymatic) formation occurs. Roridin A toxicity increases antioxidant production potential to mobilize ferritin iron this suggestion is in agreement with[34]. It may be as a result of increase urinary excretion, decreases ferritin levels and reduces liver iron in the majority of chronically transfused iron loaded of patients[35] (Table 1 and Figure 12). The mean value of ferritin was significantly increasedingoji extracttreated group as compared to the control group. This indicates that goji reduces many undesirable changes in the liver tissue due to its ability for absorbtion or elimination of the mycotoxin or inhibiting its transformation, resulting in the increase of its toxicity. This finding indicates that dried fruits of goji extract could play an important role in the protection against the adverse effects ofroridin A as a mycotoxin.

Conclusion

In conclusion, goji extract is effective in reducing oxidative stress induced by a chemical toxin. Thus, goji has a great potential use as a food supplement in protection of the liver from injuries due to exposure to toxic chemicals or other related insults. However, further mechanistic and clinical studies are warranted to establish the dose-response relationships and bio-safety aspects of Lyciumbarbarum.

References

- 1. Ciegler, A. Mycotoxins: occurrence, chemistry, biological activity. (1975) Lloydia 38(1):21- 35.

- 2. Ciegler, A., Bennett, J. W.Mycotoxins and Mycotoxicoses. (1980) Bioscience 30(8): 512- 515.

- 3. Ueno, Y. Trichothecene Mycotoxins Mycology, chemistry, and toxicology. (1989) Adv Nutr Res 3: 301- 353.

- 4. D’Mello, J.P.F., Macdonald, A.M.C. Mycotoxins. (1997) Anim Feed Sci Technol 69(1-3): 155-166.

- 5. Creppy, E.E. Update of survey, regulation and toxic effects of mycotoxins in Europe. (2002) Toxicol Lett 127(1-3): 19- 28.

- 6. Wannemacher,R.W.Jr., Bunner, D.L., Neufeld, H.A. Toxicity of trichothecenes and other related mycotoxins in laboratory animals. (1991) Mycotoxins and Animal Foods 499- 552.

- 7. Yang, G.H., Jarvis, B.B., Chung, Y.J.,et al.Apoptosis induction by the sataratoxins and other trichothecenemycotoxins: relationship to ERK, p38 MAPK and SAPK/JNK activation. (2000) Toxicol Appl Pharmachol 164(2): 149- 160.

- 8. Sudakin, D.L. Trichothecenes in the environment: relevance to human health. (2003) Toxicol Lett 143(2): 97- 107.

- 9. Thompson, W.L.,Wannemacher, R.W.Jr. Structure-function relationships of 12,13-epoxytrichothece mycotoxins in cell culture: comparison to whole animal lethality. (1986) Toxicon 24(10): 985- 994.

- 10. Stecher, G., Jarukamjorn, K., Zaborski, P., et al. Evaluation of extraction methods for the simultaneous analysis of simple and macrocyclictrichothecenes. (2007) Talanta 73(2): 251- 257.

- 11. Hughes,B.J., Taylor, M.J., Sharma R.P. Effect of verrucarin A and roridin A, macrocyclictrichothecenemycotoxins, on the murine immune system. (1988) Immunopharmacology 16(2): 79- 87.

- 12. Pestka, J.J., Forsell, J.H. Inhibition of human lymphocyte transformation by the macrocyclictrichothecenesroridin A and verrucarin A. (1988) Toxicol Lett 41(3): 215- 222.

- 13. Gan, L., Zhang, S.H., Yang, X.L., et al. Immunomodulation and antitumor activity by a polysaccharide-protein complex from Lyciumbarbarum. (2004) IntImmunopharmacol 4(4): 563- 569.

- 14. Ha, K.T., Yoon, S.J., Choi, D.Y., et al. Protective effect of Lycium Chinese fruit on carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity. (2005) J Ethnopharmacol 96(3): 529- 535.

- 15. Hughes, B. J., Hsieh, G. C., Jarvis, B. B.,et al. Effect of macrocyclictrichothecenesmycotoxins on the murine immune system. (1989) Arch Environ ContamToxicol 18(3): 388- 395.

- 16. Al-Seeni M.N. Goji Extract as Antibacterial Agent and Antioxidant on Roridin E Induced Hepatotoxicity in Male Rat. (2011) J Int Environmental Application & Science 6(1): 136-140.

- 17. 17. Caraway, W.T., Watts, N.B. Carbohydrates Fundamentals of Clinical Chemistry 3rdedn. (1987) Philadephia WB saunders 422- 447.

- 18. McGowan, M.W.,Artiss, J.D., Strandbergh, D.R., et al. A peroxidise-coupled method for colometric determination of serum triglyceride. (1983) Clin Chem 29(3): 538- 452.

- 19. Miller, N.J., Rice-Evans, C., Davies, M.J., et al. (1993) A Noval Method for Measuring Antioxidant Capacity and Its Application to Monitoring the Antioxidant Status in Premature Neonates. Clin Sci (Lond) 84(4): 407- 412.

- 20. Young, D.S., Pestaner, L.C., Gibberman, V. Effects of Drugs on Clinical Laboratory Test. (1995) Clin Chem 21(5): 1D- 432D

- 21. Beutler, B.,Cerami, A. Cachectin: More than a Tumor Necrosis Factor. (1987) N Engl J Med 316(7): 379- 385.

- 22. Mitchell, R.N.,Cortan, R.S. Cell injury, death and adaptation. (1997) Basic pathology.

- 23. Ueno, Y. General toxicology In: Trichothecenes: chemical, biological and toxicological aspects. (1984a) Elsevier 135- 146.

- 24. Luo, Q., Cai, Y., Yan, J., et al. Hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects and antioxidant activity of fruit extracts from Lyciumbarbarum. (2004) Life Sci 76(2): 137- 149.

- 25. Pai, G.P.,Habeeba, P. U.,Ullal, S.,et al. Evaluation of Hypolipidemic Effects of LyciumBarbarum (Goji berry) in a Murine Model. (2013) J Natural Remedies 13(1).

- 26. Leung, H., Hung, A., Hui, A.C.F.,et al. Warfarin Overdose Due to the Possible Effect of LyciumbarbarumL. (2008) Food and Chemical Toxicology 46(5): 1860- 1862.

- 27. Li, W., Li, Y., Wang, Q.,et al. Crude Extracts from Lyciumbarbarum Suppress SREBP-1c Expression and Prevent Diet-Induced Fatty Liver through AMPK Activation. (2014)

- 28. 28. Harfenist, E.J., Murray, R.K. Plasma proteinsimmunoglobulins and clotting factors. (1991) In Harper’s biochemistry 22nd edn 611.

- 29. Abraham, P.,Sugumar, E. Increased glutathione levels and activity of PON1 (phenyl acetate esterase) in liver of rats after a single dose of cyclophosphamide: A defense mechanism? (2008) ExpToxicol Pathol 59(5): 301- 306.

- 30. Xiao, J., Liong, E. C., Ching, Y. P., et al. Lyciumbarbarum polysaccharides protect mice liver from carbon tetrachloride-induced oxidative stress and necroinflammation. (2012) J Ethnopharmacol 139(2): 462- 470.

- 31. Cheng, J., Zhou, Z.W., Sheng, H.P., et al. An evidence-based update on the pharmacological activities and possible molecular targets of Lyciumbarbarum polysaccharides. (2014) Drug Des Devel Ther 9: 33- 78.

- 32. Yang, X., Bai, H., Cai, W., et al. Lyciumbarbarum polysaccharides reduce intestinalischemia/reperfusion injuries in rats. (2013) Chem Biol Interact 204(3): 166- 172.

- 33. Reif, D.W. Ferritin as a source of iron for oxidative damage. (1992) Free Radical Biol Med 12(5): 417- 427.

- 34. Kontoghiorghes, G.J., Pattichi, K., Hadjigavriel, M., et al. Transfusional iron overload and chelation therapy with deferoxamine and deferiprone (L1). (2000) TransfusSci 23(3): 211- 223.

- 35. Buck, W.B. Trichothecenemycotoxins.Handbook of natural toxins, Toxicology of plant and fungal compounds 6: 523- 555.