RISK ASSESSMENT OF SUICIDE IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Amresh Shrivastava1*, Avinash Desousa2, Robbie Campbell3

Affiliation

- 1Associate Professor of Psychiatry, and Consultant psychiatrist, Ambulatory care program Parkwood Institute, Mental health & Associate Scientist, Lawson Health Research Institute, The Western University, London Ontario, Canada

- 2Senior Research Associate, LTMG Hospital and Medical College Mumbai, & Mental health resource foundation, Mumbai, India

- 3Professor Emeritus Parkwood Institute, Mental health The Western University, London Ontario, Canada

Corresponding Author

Amresh Shrivastava, Parkwood Institute, Mental health, 550 Wellington Road, London, ON N6C 0A7, Tel: (519) 646-6100; E-mail: dr.amresh@gmail.com

Citation

Shrivastava, A., et al. Risk Assessment of Suicide in Clinical Practice. (2015) J Addict Depend 2(4): 1- 5.

Copy rights

© 2016 Shrivastava, A. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Suicide; Training; Risk assessment; Risk factors

Abstract

Suicide is a global public health problem. Its management in clinical practice is complex and challenging .Studies show about 26% suicide in mental health system. Out of these, 14% commit suicide during hospital stay; about 50 - 90% have at least one psychiatric diagnosis. 60 - 70% of patients are hospitalized due to an attempt or potential crisis, about 15 - 20% attempt suicide prior to admission. Suicide is also common in post-discharge period. Every psychiatrist on an average loses atleast on client due to suicide in an average span of 20 years of practice. In about 70% of cases, suicide behavior is there as on for hospitalization in acute settings. Continuous training and skill development are two of the most important measures in clinical practice for dealing with suicide behavior. High suicide rates are reported in prodromal stage, acute illness, post-hospitalization and soon after discharge in the community. A clinician faces challenging situations while determining the level of care and referral for a patient with a high suicide potential. There is continued struggle amongst clinicians for decision- making in regards to the need for hospitalization, level of monitoring, voluntary status, and time of discharge. It is generally agreed that suicide is difficult to predict and prevent; however, in order to develop clinical excellence and offer a standard of care, continued education and knowledge translation for bringing research into practice is the least that can be done. Inspite of this need, continued education for mental health professionals and psychiatrists in-training remains limited.

Introduction

Suicide is a public health problem that kills about a million people across the world every year. It presents as the most serious psychiatric emergency. Identification and assessment of suicidality is a skill that every physician needs to have, whether working in an emergency room, a general hospital, in community settings or in a tertiary psychiatric hospital. Decisions for disposition of a suicidal client always depend upon a qualitative and comprehensive risk assessment.

Risk assessment is a clinical art which every clinic an develops through experience and training; though each has his own style and method, it is expected to be comprehensive consisting of necessary dimensions of risk.

Risk assessment is neither preventive nor predictive. It has a very low validity specificity and sensitivity with high rates of false positive and false negative outcomes. A good risk assessment can be one of the finest clinical assets in difficult situations for decision-making. The purpose of this short article is to highlight salient features regarding risk, risk factors and risk assessment that can be useful in day-to-day clinical work.

Skills of risk assessment of suicide behavior are required by health as well non-health professionals across medical and non-medical settings because suicide prevention is everybody’s business. Risk assessment is required in a number of situations and settings: emergency rooms, physician’s offices, in general practice, at psychiatric outpatients, at help lines and crisis centers, admitting wards, etc. Risk assessment is performed for every patient that:

1. is expressing suicidal ideas.

2. has a known psychiatric history.

3. currently has an acute psychiatric condition.

4. seemed at-risk during screening for mental health problems

5. is being hospitalized for psychiatric condition.

6. is a known psychiatric patient now being admitted for general medical condition.

7. undergoing current

8. has high risk factors (as detailed further) like repeated and past history, family history of suicide etc.

Risk assessments are done in number of settings like: emergency rooms, psychiatric outpatient, primary care, general medical wards, post-operative and intensive care settings, crisis centers, day hospitals for crisis beds, telephone helplines, psychiatric outpatients, psychiatric acute services, community psychiatry settings, early intervention programs, sometimes in special settings like jails, prisons, schools, workplaces and legal justice systems.

In every setting and in every situation, the format, content and method of risk assessment varies to some extent depending upon the client’s level of comfort, engagement of the patient with the therapist and the availability of collateral data. Collateral data and objective in formation from referring sources, accompanying persons, family members, significant others, friends and colleagues from workplace is of great value in determining level of risk and for the planning of disposition and care.

Responsibility of risk assessment is not limited to clinicians and psychiatrists. It’s mandatory that health and non-health professionals (anyone who comes in contact with vulnerable population) should have atleast basic knowledge and competence for identification and intervention in crisis situations.

It is unfortunate that in formal and informal education and in contents of curriculum, chapters about suicide prevention are often missing despite the fact that studies showing intervention in suicide behavior and crisis as life-saving measures show 90% of primary care physicians and 50% of residents expressing the need for more training and education.

Risk assessment is a clinical skill, which needs to be mastered by nurses, social workers, emergency room clinical staff and other mental health as well as general health professionals; there is a significant gap in the training and education for risk behavior. The concept of risk has been continuously evolving. Suicide risk is dynamic and it varies from time to time. Sometimes, the risk is lethal enough to outweigh an individual’s scoping mechanism and tolerance. Severity of risk normally builds up gradually due to a combination of risk factors.

Clinical challenges Appropriate assessment and decision for disposition based upon interpretation of risk is a great responsibility. In every case of risk assessment, clinician shave to consider a number of issues that may affect both the patient as well as the physician.

Most common questions and actions that every clinician faces are:

1. Is the patient at risk of suicide?

2. Is the patient at risk of suicide to a degree that needs immediate attention?

3. Does the patient have the level of risk that cannot be treated on an outpatient basis?

4. Does the patient need to be hospitalized as a voluntary or in voluntary status?

5. Carry out an assessment of suicide during the stay in the hospital to monitor the progress

6. Carry out an assessment of suicide to decide fitness for discharge

7. Determine the level of risk before sending patient on leave of absence, and can the risk be managed with the given resources in the community?

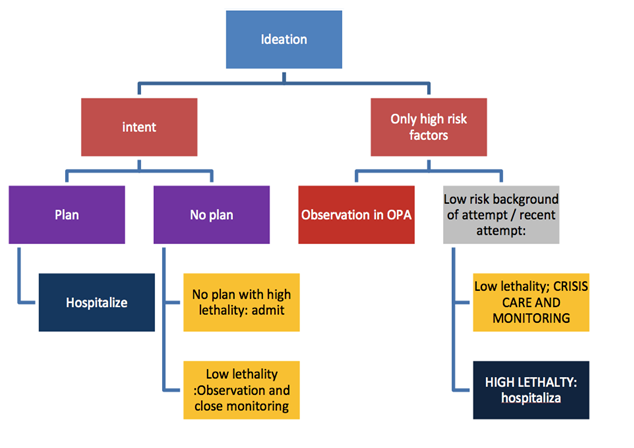

An algorithmic pathway can be helpful for decision- making [see figure1 below]

There is a very small gap between suicidal ideation and attempt. The pathological process of progression from ideation to action is not clear. The pathway is ill defined and consequently there have been a number of missed opportunities of treatment where intervention could have been done[1]. A number of studies have shown risk factors have poor predictability even when an algorithm of 2 and 3 factors is considered together.

‘Why is suicide unpredictable?’ is an interesting topic, but is out of scope of this chapter. Suicide risk is multi factorial; Cultural and ethnic factors should always be considered while assessing the risk, particularly in catchment of immigrants, who are a right risk people[2].

Dealing with incident of suicide in clinical practice

Every clinician in his practice of about 20 years, loses atleast one patient to suicide; it is a devastating experience for staff members who have been involved in the care of the patient. Suicide, whether in inpatient or outpatient care, is a devastating experience. In such situation a clinician should review a whether delivery of established standard of care was met with, and whether basic minimum treatment and prevention was carried out. Every physician worries about how the patient’s family will react. It is important that the physician establishes contact with the family, offers a family meeting with multidisciplinary team members to explain complexities and the progress of the illness and try to debrief the members of the family.

There are always differing opinions and reactions within members of the family and members of the team are required to be prepared with facts. Reviewing some of literature is always helpful. In the era of Internet, it is expected that relatives will certainly review the matter and want to be assured that necessary steps were taken.

Besides dealing with emotions of the families, legalities should also be considered to ensure that the physician is on firm ground. Opinions of and documentation by the team members are very helpful and a chronological log of decisions and the implementation of care plan should be maintained to be ready to respond to any queries. There are two legal parameters for satisfactory care of a person who has committed suicide[1]. Whether, in similar situation for similar person, whatever a contemporary colleague will do was done[2]; whether, whatever was done or not done was reflective and recorded. The physicians should know the following:

A. Established standard of care?

B. Basic minimum prevention?

C. What would our colleagues do?

D. Evidence or reflection of work done or not done

E. Whether delivery of an established standard of care was met with.

F. Whether basic minimum treatment and prevention were carried out.

Standard of care has been defined by a number of organizations e.g. National institute of mental health (NIMH), American Psychiatric Association (APA), National institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE), American Association of Suicidology (AAS), International Association of Suicide Prevention (IASP)

There is continued struggle amongst clinicians for decision- making in regards to the need for hospitalization, level of monitoring, voluntary status, and time of discharge. It is generally agreed that suicide is difficult to predict and prevent; however, in order to develop clinical excellence and offer a standard of care, continued education and knowledge translation for bringing research into practice is the least that can be done. Inspite of this need, continued education for mental health professionals and psychiatrists in training remains limited.

Risk factors

Risk factors have been conceptualized in a number of ways e.g. modifiable and non- modifiable, static and dynamic, biological and psychosocial, state and trait risk, etc[3,4]. The simplest way to discuss risk factors is to classify the masons that have been present for a long time and are inherent to individual’s personality, and as ones that are transitory. Not all factors can be changed and therefore while assessing a patient one should consider[1]: Inherent risks and their severity (specificity)[2]. Factors which have culminated recently[3]. Factors which are protective and can be treated in short and long term. Literature marks hundreds of risk factors, however, clinically significant ones are necessary to be assessed during a clinical examination.

These include recent heavy drinking, affective disorder, threat or talk of suicide, living alone, unemployment, low socio-economic status, low social support use of sedative-hypnotics, hopelessness, drug misuse, a recent loss, unipolar depression, dysthymia, suicidal behavior before admission, positive symptoms, presence of good in sight, presence of residual symptoms, history of poor response to treatment and suicide in early phase, personality disorder, age older than 45 years, history of using a potentially hard method for suicide and evidence of a repeated suicide attempt, low depression hopelessness, better cognition, low anxiety-hostility, high level of functioning, reduction in positive symptoms, symptom remission-global, low EPS-Anesthesia and low persistent symptoms.

Vulnerabilities may arise from a number of physical and psychiatric conditions; however, biological changes also contribute to emotion of depression and hopelessness because of impaired decision making and problem solving capacities. Attempts of bereavement, hospitalization, recent discharge and psychosocial stress are some other risk factors. People with a family history of suicide are specifically at high risk for suicide.

Common risk factors always interplay with a number of psychological factors, e.g. Childhood anxiety, major depression, Schizoid ,avoidant, dependent, passive-aggressive, schizotypal and borderline traits, problem-solving deficits, cognitive rigidity, hopelessness, Alexithymia, negative self evaluation, negative affectivity and poor autobiographical recall.

A family history of suicide and family history of mental disorders both are high-risk and highly specific risk factors. As in all mental disorders the question of features that are inherited is also involved here[5]. Understanding a few endopheno types of suicide behavior have been described in both biological and clinical characteristics, which to some extent explain the heterogeneity in suicide behavior; clinical intermediate endophenotypes help a great deal. These are Aggressive behavior Impulse Dyscontrol, poor coping and low frustration tolerance[6].

There are other factors that are important in patients who have repeated suicide. Common risk factors of suicide in persons with previous suicide attempt(s) and psychiatric disorders include major depression, mixed drug abuse, bipolar disorder, dysthymia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, schizophrenia and personality disorder[7].

There are number of situations where there is no psychiatric diagnosis in attempted suicide. Sociocultural factors a remainly responsible for such attempts. Amongst the population of first-episode patients 10% make atleast one attempt prior to contact with services. A high percentage of undiagnosed individuals complete suicide.

Subjects who are at risk mental states or at a prodromal phase of psychosis and depression, experience have experienced substance abuse, first episode of illness, chronic physical disorders-mainly cancer and renal diseases, recent loss hopelessness, presence of depression, history of depression, previous attempt, repeated attempt, childhood trauma[8,9], history of sex abuse or physical abuse, bereavement, potential psychosocial stress, trauma multiple drug abuse, transitional stages in psychopathology, eighth responding or progression of illness, first episode of illness, homelessness and poor psychosocial, family and personal support. These are some of the common risk factors, which must be inquired and assessed for intent, plan and lethality[10,11].

In about 70 - 80% of suicide attempts, psychiatric illnesses are the main cause. Further, in more than 50 - 60% of cases comorbidity is present commonly between personality disorder, substance-use disorder, alcoholism, schizophrenia and affective disorder. Most significant comorbidity is that of bipolar disorder or substance abuse.

The life time risk of suicide is 15% in affective disorder 10% in schizophrenia and 2 - 3% in alcohol is mand substance abuse. Amongst affective disorder, suicide is commonest in bipolar depression. Repeated suicide attempts are the commonest problem in clinical practice. The risk of death by suicide amongst the patients who make repeated attempts is about 20 - 25 times to that amongst patients who don’t. Main characteristics of such patients are presence of comorbidity, cognitive factors, problem solving deficits and hopelessness. Suicide behavior and psychiatric illnesses have a complex interrelationship. Some patients of mental disorder attempt suicide while others live with low severity of suicidal ideation for long number of years. Follow up studies show that suicidality persists even after recovery in mental disorders in the long term.

;Risk assessment and Identification of patients ‘at risk’

&emspThe identification of suicide is a complex clinical condition. Most difficult aspects like suicide behavior cannot be predicted[12]; whilst carrying out a risk assessment we have three main questions: (1) How to assess? (2) How to evaluate? and (3) what do we want to know? Will the information have gathered aid in prevention of further suicide? The clinical interview needs to be customized and optimized for every patient, depending upon there ferral system, current clinical state and availability of collateral data. After the interview, physicians should be ready with information about the degree of intent for suicide content and severity of ideation, planning of suicide-currently and in the future, content of suicidal ideation, duration of ideas and plans, psychiatric diagnosis, some information about resilience, individual’s response to changes in psychological and stressful situation and finally, findings from mental state examination.

While it is also true that patients mostly communicate with doctors, a number of patients with high degree of sociality and a definite plan never reveal it. Therefore, a physician is required to have high degree of clinical acumen to sense and identify the degree and nature of suicidality. Evidence suggests that neither suicide contract nor close monitoring is sufficient to prevent suicide. A number of suicides have happened under constant observation as well as after developing a safety contract. It is important to see patients frequently to develop a therapeutic alliance and to develop a situation in which patient starts thinking about the alternatives.

There are number of limitations in risk assessment which compromise its validity. There are too many factors and too many variations in risk assessment. There are no specific psychological or biological markers. There is high degree of false positive and false negative results.

The American Psychiatric Association recommends that a systematic assessment should be carried out which involves identifying multiple contributing factors, conducting a thorough psychiatric examination, identifying risk and protecting factors, distinguishing modifiable and non-modifiable factors, determining level of risk (low, moderate or high), determining treatment setting and plan, investigating details about past and present suicidal ideation, plans, behavior and intent and asking about plans or method of suicide.

Compressive risk assessment involves the following[13]:

A. Step 1. Detect predisposing factor; a. Axis I disorder; 1b. Specific suicide inquiry. What are the thoughts? Are they active or passive? When did they begin?

B. How frequent are they? How persistent are they? Are they obsessive? Can you control them? Do they command hallucination?

C. Step 2. Identify or detect a predisposing factor

D. Step 3. Detecting potentiating factors like family history, personality disorders, life stressors, physical illness and access to lethal means of suicide.

E. Step 4. Determine the level of intervention: a distinguishing disorder-based suicidality from personality-based suicidality.

F. Step.5 Provide documentation for Assessment, Degree of risk, Objective data, Subjective data Diagnosis, working for differential diagnosis. This includes: Treatment plan, Risk-benefit analysis, Basis for decision making; Relevant medications, Tests, Consultation, Precaution and privileges, Reassessment of suicidality.

G. Step 6 Times to assess: Assess and document upon first examination/admission, with occurrence of any suicidal behavior, whenever there is not worthy clinical change, whenever sociality is an issue for an inpatient, before increasing privileges or giving passes and before discharging a patient[14].

There are number of structured and valid scales available for quantitative risk assessment, however these scales are only useful when a clinical decision is difficult and for research purposes. If a clinician issue in his clinical wisdom about what is to be done, these scales are not normally required[14].

APA recommendations state: Identify the multiple contributing factors, conduct a thorough psychiatric examination, identify risk factors and protective factors, distinguish modifiable and non-modifiable factors, ask directly about suicide, determine level of suicide risk (low, moderate, high), Determine treatment setting and plan, investing at past and present suicidal ideation, plans, behaviors, intent; methods; hopelessness, hedonia, anxiety symptoms; reasons for living; associated substance use; homicidal ideation. What is to be assessed in risk assessment is the prediction and systematic assessment of INTENT? An examination of MOTIVES for suicidal act predictive value of each risk factor remains low.

Warning signs are also helpful for getting some idea about the condition of a patient. Though warning signs are for public health intervention and education of relatives, overall these are significant. These include expressing suicidal feelings or bringing up the topic of suicide, giving away prized possessions, settling affairs, making out a will, signs of depression, sad mood, alterations in sleeping/eating patterns, change of behavior (poor work or school performance), risk-taking behaviors, increased use of alcohol or drugs; losing interest in their personal appearance, social isolation or developing a specific plan for suicide.

Limitations in Risk Assessment

There are too many factors and, too many variations on the subject. A new definition of suicide needs to be found. Though several psychological & biological markers exist, none are free from false positive and false negative results.

To surmise risk assessment is most important skill that clinicians across the disciplines require. Suicide behavior is complex, it cannot be predicted and there for entire management depends upon outcome of risk assessment. Experience shows that it has never been sufficient and scope of learning, education and training continues.

References

- 1. Olsson Hither psychiatric risk assessment. A virtually impossible task that (in France) may lead to prosecution and punishment]. (2013) Lakartidningen 110(6): 290

- 2. Neuner, T., Schmid, R., Wolfersdorf, M., et al. Predicting inpatient suicides and suicide attempts by using clinical routine data?. (2008) Gen Hosp Psychiatry 30(4): 324- 330.

- 3. Goldston, D.B., Reboussin, B.A., Daniel, S.S. Predictors of suicide attempts: state and trait components. (2006) J Abnorm Psychol 115(4): 842-849.

- 4. Nakagawa, M., Kawanishi, C., Yamada, T., et al. Characteristics of suicide attempters with family history of suicide attempt: a retrospective chart review. (2009) BMC Psychiatry 9: 32.

- 5. Diaconu, G., Turecki, G. Family history of suicidal behavior predicts impulsive-aggressive behavior levels in psychiatric outpatients. (2009) J Affect Disord 113(1-2): 172-178.

- 6. Hawton, K., Casañas I Comabella, C., Haw, C., et al. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. (2013) J Affect Disord 147(1-3): 17-28.

- 7. Hooven, C., Nurius, P.S., Logan-Greene, P., et al. Childhood Violence Exposure: Cumulative and Specific Effects on Adult Mental Health. (2012) J Fam Violence 27(6): 511-522.

- 8. Carballo, J.J., Harkavy-Friedman, J., Burke, A.K., et al. Family history of suicidal behavior and early traumatic experiences: additive effect on suicidality and course of bipolar illness?. (2008) J Affect Disord 109(1-2): 57-63.

- 9. Bakst, S., Rabinowitz, J., Bromet, E.J. Antecedents and Patterns of Suicide Behavior in First-Admission Psychosis. (2009) Schizophr Bull 36(4): 880-889.

- 10. Sanchez-Gistau, V., Baeza, I., Arango, C., et al. Predictors of suicide attempt in early- onset, first-episode psychoses: a longitudinal 24-month follow-up study. (2013) J Clin Psychiatry 74(1): 59-66.

- 11. Carter, G.L., Safranko, I., Lewin, T.J., et al. Psychiatric hospitalization after deliberate self-poisoning. (2006) Suicide Life Threat Behav 36(2): 213-222.

- 12. Practice guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Patients With Suicidal Behaviors.

- 13. Desai, R.A., Dausey, D., Rosenheck, R.A. Suicide among discharged psychiatric inpatients in the Department of Veterans Affairs. (2008) Mil Med 173(8): 721-728.

- 14. Allen, M.H., Abar, B.W., McCormick, M., et al. Screening for suicidal ideation and attempts among emergency department medical patients: instrument and results from the Psychiatric Emergency Research Collaboration. (2013) Suicide Life Threat Behav 43(3): 313-323.