Study on Relationship Between DNA Content and Other Prognostic Factors in Iranian Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL).

Shahidi Minoo1,2*, Rakhshan Mohammad3, Farhadi Mohammad4

Affiliation

- 1Tarbiat Modares University, Iran

- 2 Iran University of Medical Sciences, Iran

- 33Shahid Beheshti university of Medical Sciences,Tehran, Iran

- 4Iranian blood transfusion organization, Iran

Corresponding Author

Dr. Minoo Shahidi, Hematology Department, School of Allied Medical Science, Iran University of Medical Science, Shahid Hemmat Highway, 14155-5983, Tehran, Iran. Fax: +00982188052264; Tel: +00982182944707; E-mail: ms1989ir@yahoo.com

Citation

Shahidi M., et al. Is DNA Index Measurement A Helpful Tool to Evaluate Iranian Children With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)? (2016) Int J Hematol Therap 2(1): 1-4.

Copy rights

©2015 Shahidi M. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Abstract

Aims and Background: The measurement of DNA content or ploidy has become a useful tool for diagnosis and treatment of malignancies particularly in patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) as it has been associated with the most favorable prognosis in these patients. The purpose of this study was to assess the incidence of DNA aneuploidy in Iranian children with ALL and the relationship between aneuploidy and morphological subclass, immunological phenotype, leukocyte count, age and sex in Tehran’s hospitals.

Methods: DNA content and laboratory features were determined in 70 ALL patients from Tehran’s hospitals, all of whom were under 15 years old and have not received any treatment. The morphological phenotype of the blasts was analyzed by microscopic examination. DNA content, the phenotype of the lymphoblast and WBC count were detected in the blood using flow cytometry.

Results: Diploidy, hyperdiploidy and hypodiploidy were reported in 50, 45 and 5% among the cases, respectively. The mean DNA index in hyperdiploid patients was 1.21 and hyperdiploidy was found to be associated with lower leukocyte count (p < 0.001), lower age, L1 morphology and early pre-B immunophenotype.

Conclusions: This study showed that detected DNA index in Iranian children with ALL is associated with some favorable prognostic factor such as WBC count, age, immunological phenotype and FAB classification but that there is a need for further validation using extra molecular methods.

Introduction

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL) is the most common malignancy of childhood which is associated with a clonal proliferation of lymphoblast cells in bone marrow and a sharp peak in incidence among children aged 2–5 years[1,2].

Various genetic alterations have been discovered in ALL, but hyperdiploidy has been known to be a favorable prognostic factor in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. In contrast hypodiploidy has been introduced with a poor clinical outcome[3]. However high-hyperdiploidy and near haploid ALL are also reported to be associated with a unfavourable prognosis[4-9]. In addition it is reported that the existence of i(17q) exerts an adverse influence on treatment outcome in ALL, even in hyperdiploid cases[10].

Prognostic factors in children with ALL include age of child at diagnosis, race, gender, white blood cell counts, immunophenotyping, genetic abnormalities and response to early treatment. However there is clear evidence that DNA analysis of leukemic blast cells contributes important prognostic information in these patients[11-14].

The purpose of this study was to assess the incidence of DNA aneuploidy using DNA index in Iranian children with ALL and its relationship with immunological phenotype, FAB classification, leukocyte count Age and sex.

Methods

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) anti coagulated peripheral blood samples obtained from 70 patients with lymphoblastic leukemia and 70 normal, healthy cases from hospitals of Tehran. All of the patients and the controls were between 1-15 years of old and patients tested before taking any treatment to prevent drug interaction.

All specimens were obtained and prepared for morphological examination using standard techniques. Peripheral blood smears were stained with Wright- Giemsa and examined under light microscopy and a scoring system for types L1 and L2 was carried out based on French-American-British Criteria (FAB).

Immunophenotyping

Mononuclear cells were isolated and stained with various combinations of Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC) and Phycoerythrin (PE - Labeled Monoclonal Antibodies, Sigma).

The panel of antibodies (all from Sigma) was used in distinct myeloid series (CD13, CD33 and CD14) from lymphoid and B cells from T cells (CD19, CD3 and CD7). CD10 (CALLA) antibody was also used to show the early pre-B phenotype. The last antibody was against Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase (TdT) which is a useful marker in the diagnosis of ALL, L1 and L2 and mature B-lymphoid neoplasms or L3 phenotype.

DNA Analysis

To investigate DNA content all samples were treated with 1% Triton-100X to increase the permeability of the cell membrane. Treating the cells with ribonuclease (50 μl of a 100 μ/ml sock of RNase) was performed to remove RNA. Propidium Iodide (200 μl PI from 50 μg/ml stock solution) was used as a DNA-binding flurochrome and the samples were analyzed by flow cytometry. The DNA index was distinct as the modal DNA content of blasts compared to that of normal lymphocytes.

Results

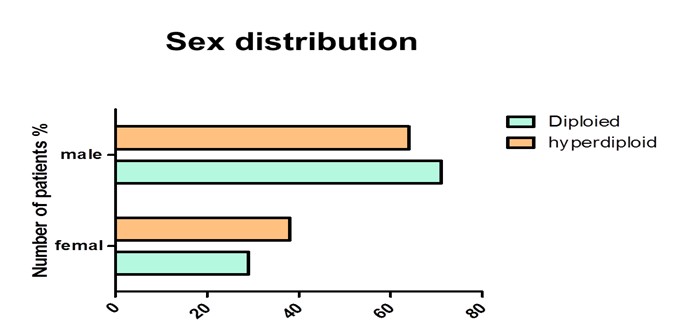

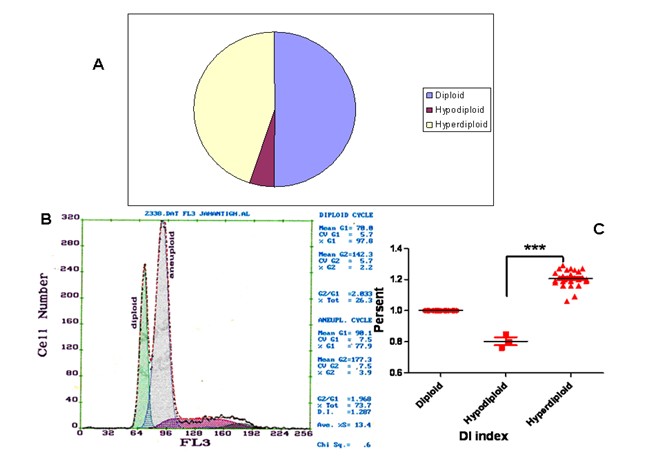

Our data showed the percentage of female and male 37% and 63% respectively in hyperdiploid group, whereas in diploid group it was 30% and 70% respectively (Figure 1) The results of DNA analysis showed the diploidy, hyperdiploidy and hypodiploidy 50%, 45%, and 5% among the patients respectively. A mean DNA Index (DI) of 1.21 was detected among the hyperdiploid patients (Figure 2). All the controls showed a single diploid pick in their DNA content histograms with a DI = 1.

Figure 1: The histogram shows the percentage of female and male in both diploid and hyperdiploid group

Figure 2: (A) Distribution of poloidy among the tested cases. (B) Representative histogram of diploid and hyperdiploid cell population. (D) Comparison of DNA index (DI) between three groups (diploid, hypodiploid and hyperdiploid) as measured by flow cytometry, where *** =p < 0.0001.

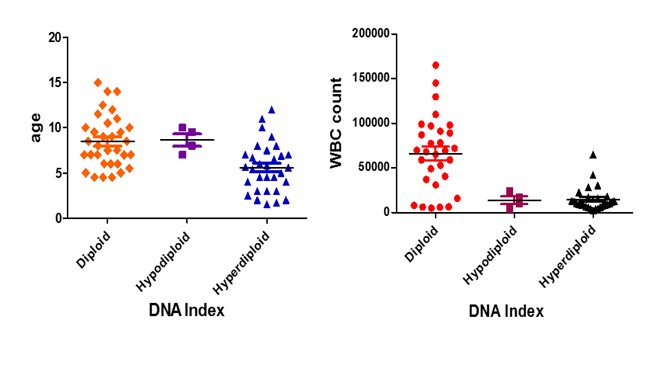

The mean age in diploid, the hyperdiploid and hypodiploid group was 8, 5.8 and 9.3 respectively as it is shown in (Figure 3 left). The mean WBC count in diploid, hyperdiploid and hypodiploid group was 8, 5.8 and 9.3 respectively as it is presented in (Figure 3 right).

Figure 3: Comparison of age distribution between the diploid and hyperdiploid groups (left) and WBC distribution between diploid and hyperdiploid (right), where * p < 0.05 and *** =p < 0.0001

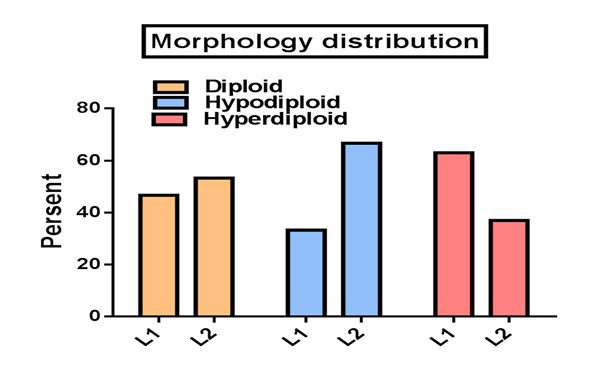

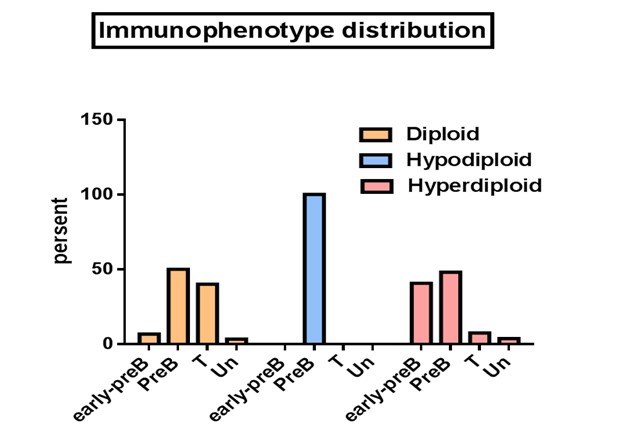

In hyperdiploid group L1 and L2 morphology were 63% and 37% whereas diploid group showed a percentage of 46.7 and 53.3 respectively (Figure 4). When the flow cytometric immunophenotyping data were correlated with the DNA contents, the cases with hyperdiploid showed a phenotype of early pre-B (40.7%), pre -B (48.1%), T (7.4%) and unclassified (3.7%), whereas diploid group showed an early pre-B (6.7%), pre -B (50%), T (40%) and unclassified (3.3%). Although just a few presents of our patients had been hypodiploid, they all demonstrated a pre-B immunophenotype (Figure 4 &5).

Figure 4: Comparison of Morphology distribution between the poloidy groups as detected by microscopy and FAB classification.

Figure 5: Comparison of immunophenotype distribution between the poloidy groups as measured by flow cytometry

Discussion

Hyperdiploidy is the most frequent cytogenetic abnormality pattern in children with B-cell precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL), occurring in 25-30% of such case[5]. DNA hyperdiploidy is known to be associated with a good prognosis in childhood ALL although the reason for this prognostic significance is not fully understood it could be related to differences in cellular drug resistance[15,16].

All of our control samples showed a single diploid pick in their DNA content histograms with a DI = 1, as it was expected. The percent of hyperdiploid cases among our patients was 45% which was higher than previous reports[17], but nearly comparable with another investigation in middle east population reporting a percentage of 41%[15] suggesting a regional or race dependent reason. The mean of DI index in our samples was equal to 1.21, which was again higher than previous study which showed a DI greater than or equal to 1.16[17]. Our results confirm the Kaspers et al findings, who reported the DNA index between 1.16 and 1.35 in hyperdiploid patients[18]. The results showed a lower WBC count among hyperdiploid cases, which was statistically significant, when compared with diploid patients (p < 0.0001) indicating a good prognosis in hyperdiploid patients, which was in agreement with a previous study[19,20].

A positive correlation was found between L1 morphology and hyperdiploidy, as patients with a hyperdiploid peak in their histogram showed L1 morphology, indicating a possible favorable prognosis in this group. However, a better outcome for L1 and a higher relapse time for L2 have been established previously[21-23].

Since cases with L3 morphology are uncommon, we could not find any cases with this morphology in our study. This type is uncommon and associated with a poorer prognosis[24]. The number of female patients among hyperdiploid population was higher than hypodiploid, indicating a more favorable outcome in this group, as it has been established previously[20].

The phenotype is very imperative to determine the treatment protocol that the patient may receive. Acute lymphoblastic leukemias fall into one of the known immunophenotypes including early pre-B, pre-B, B-cell and T-cell. It is stabilished that the prognosis for T- and B-cell ALL used to be poorer than for the pre-B ALLs. In the present study, early pre-B immunophenotype (the presence of CD10 or CALLA positive and the lack of cytoplasmic or surface immunoglobulins), which is associated with a favorable prognosis were found more in the hyperdiploid cases indicating a possible better outcome in these patients. This was similar to another study in the middle east[25]. The number of patients with T cell phenotype was significantly higher in diploied group when compared with hyperdiploid indicating a poorer prognosis in the first group. Unexpectedly we found a number of patients with T phenotype, which are thought to be linked with a poor prognosis[25], but with a hyperdiploid phenotype. However The same result has been reported previously[27]. This indicates that molecular cytogenetic studies must be associated with DNA index measurement to identify and characterize chromosomal rearrangements. Further investigations, therefore, are needed for our T-ALL patients, to be able to compare with the results of studies in other areas[28-30].

A lower incidence of hyperdiploidy was found in elder patients compared with younger, which was statistically significant when compared with diploid and hyperdiploid group (p < 0.05 and p < 0.0001 respectively). This was in agreement with the previous reports[2,15,31], indicating the highest frequency of hyperdiploidy between ages of 2 and 7, which could be associated with a good outcome. In addition, we found a group of patients with T cell phenotype, who showed a positivity for CALLA antigen, suggesting further molecular studies such as cytogenetic in this group. However, it was previously reported that within T-ALL the expression of CALLA might be prognostically important[32].

Conclusion

Taken together, this study showed that hyperdiploidy in Iranian children with ALL is associated with some favorable prognostic factor such as WBC count age, immunological phenotype and FAB classification, but there is a need for further validation via measuring additional prognostic markers.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank the Tarbiat modares University for ‘seed funding’ for this project.

References

- 1. Michel, G., et al. Incidence of childhood cancer in Switzerland: the Swiss Childhood Cancer Registry. (2008) Pediatr Blood Cancer 50(1): 46-51.

- 2. Forestier, E., Schmiegelow, K. The incidence peaks of the childhood acute leukemias reflect specific cytogenetic aberrations. (2006) J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 28(8): 486-495.

- 3. Holmfeldt, L., Wei, L., Diaz-Flores, E., et al. The genomic landscape of hypodiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia. (2013) Nat Genet 45(3): 242-252.

- 4. Sunil, S.K., et al. Adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia with near haploidy, hyperdiploidy and Ph positive lines: a rare entity with poor prognosis. (2006) Leuk Lymphoma 47(3): 561-563.

- 5. Heerema, N.A., et al. Prognostic impact of trisomies of chromosomes 10, 17, and 5 among children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and high hyperdiploidy (> 50 chromosomes). (2000) J Clin Oncol 18(9): 1876-1887.

- 6. Shikano, T., et al. [Hyperdiploidy (greater than 50 chromosomes) has the most favorable prognosis among the major karyotypic subgroups of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia]. (1990) Rinsho Ketsueki 31(3): 308-314.

- 7. Brodeur, G.M., et al. Near-haploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a unique subgroup with a poor prognosis? (1981) Blood 58(1): 14-19.

- 8. Gibbons, B., et al. Near haploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia: seven new cases and a review of the literature. (1991) Leukemia 5(9): 738-743.

- 9. Kimura, M., et al. [Adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia presenting a near haploid karyotype]. (2000) Rinsho Ketsueki 41(9): 764-767.

- 10. Pui, C.H., Raimondi, S.C., Williams, D.L. Isochromosome 17q in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: an adverse cytogenetic feature in association with hyperdiploidy? (1988) Leukemia 2(4): 222-225.

- 11. Duque, R.E., et al. Consensus review of the clinical utility of DNA flow cytometry in neoplastic hematopathology. (1993) Cytometry 14(5): 492-496.

- 12. Kaneko, Y., et al. Correlation of karyotype with clinical features in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. (1982) Cancer Res 42(7): 2918-2929.

- 13. Lowery, M.C., Bull, R.M., Sciotto, C.G. Identification of hyperdiploidy in fixed cells from pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia cases using flow cytometry and cytogenetic analysis. (1993) Cancer Genet Cytogenet 67(2): 136-140.

- 14. Wang, X.L., et al., Flow cytometric DNA-ploidy as a prognostic indicator in oral squamous cell carcinoma. (1990) Chin Med J (Engl) 103(7): 572-575.

- 15. Al-Bahar, S., Zamecnikova, A., Pandita, R. Frequency and type of chromosomal abnormalities in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients in Kuwait: a six-year retrospective study. (2010) Med Princ Pract 19(3): 176-181.

- 16. Evans, W.E., et al. Clinical pharmacology of cancer chemotherapy in children. (1989) Pediatr Clin North Am. 36(5): 1199-1230.

- 17. Whitehead, V.M., et al. Accumulation of high levels of methotrexate polyglutamates in lymphoblasts from children with hyperdiploid (greater than 50 chromosomes) B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. (1992) Blood 80(5): 1316-1323.

- 18. Kaspers, G.J., et al. Favorable prognosis of hyperdiploid common acute lymphoblastic leukemia may be explained by sensitivity to antimetabolites and other drugs: results of an in vitro study. (1995) Blood 85(3): 751-756.

- 19. Cytogenetic abnormalities in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: correlations with hematologic findings outcome. A Collaborative Study of the Group Francais de Cytogenetique Hematologique. (1996) Blood 87(8): 3135-3142.

- 20. Secker-Walker, L.M., et al. Chromosomes and other prognostic factors in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a long-term follow-up. (1989) Br J Haematol 72(3): 336-342.

- 21. Bennett, J.M., et al. The morphological classification of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: concordance among observers and clinical correlations. (1981) Br J Haematol 47(4): 553-561.

- 22. Viana, M.B., Maurer, H.S., Ferenc, C. Subclassification of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children: analysis of the reproducibility of morphological criteria and prognostic implications. (1980) Br J Haematol 44(3): 383-388.

- 23. Lilleyman, J.S., et al. French American British (FAB) morphological classification of childhood lymphoblastic leukaemia and its clinical importance. (1986) J Clin Pathol 39(9): 998-1002.

- 24. Mazoyer, G., et al. B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: clinical and biological aspects. (1988) Clin Lab Haematol 10(2): 149-157.

- 25. Hamouda. F., El-Sissy, A.H., Radwan, A.K., et al. Correlation of karyotype and immunophenotype in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia; experience at the National Cancer Institute, Cairo University, Egypt. (2007) J Egypt Natl Canc Inst 19(2): 87-95.

- 26. Dowell, B.L., et al. Immunologic and clinicopathologic features of common acute lymphoblastic leukemia antigen-positive childhood T-cell leukemia. A Pediatric Oncology Group Study. (1987) Cancer 59(12): 2020-2026.

- 27. Healey, K., et al. Hyperdiploidy with trisomy 9 and deletion of the CDKN2A locus in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. (2009) Cancer Genet Cytogenet 190(2): 121-124.

- 28. Inukai, T., Kiyokawa, N., Campana, D., et al. Clinical significance of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: results of the Tokyo Children's Cancer Study Group Study L99-15. (2012) Br J Haematol 156(3): 358-365.

- 29. Rachieru-Sourisseau, P., Baranger, L., Dastugue, N., et al. DNA Index in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a karyotypic method to validate the flow cytometric measurement. (2010) Int J Lab Hematol 32(3): 288-298.

- 30. Quijano, S.M., Torres, M.M., Vasquez, L.E., et al. [Correlation of the t(9;22), t(12;21), and DNA hyperdiploid content with immunophenotype and proliferative rate of leukemic B-cells of pediatric patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia]. (2013) Biomedica 33(3): 468-486.

- 31. Nachman, J.B. Adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a new "age". (2003) Rev Clin Exp Hematol 7(3): 261-269.

- 32. Dowell, B.L., Borowitz, M.J., Boyett, J.M., et al. Immunologic and clinicopathologic features of common acute lymphoblastic leukemia antigen-positive childhood T-cell leukemia. A Pediatric Oncology Group Study. (1987) Cancer 59(12): 2020-2026.