Survey of the Fluoride Concentration in Drinking Water Sources and Determination of DMFT Index in 9-12 Years Old Students in Garmsar City, Semnan, Iran

Fateme Goodarzi, Nahid Vahidi

Affiliation

Department of Environmental Health, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Corresponding Author

Safiye Ghobakhloo, Department of Environmental Health, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran, Tel: 98 919 1323815/ Fax: 98 23 33448999; E-mail: sa_ghobakhloo@yahoo.com

Citation

Ghobakhloo, S., et al. Survey of the Fluoride Concentration in Drinking Water Sources and Determination of DMFT Index in 9-12 Years Old Students in Garmsar City, Semnan, Iran. (2018) J Environ Health Sci 4(1): 13- 19.

Copy rights

© 2018 Ghobakhloo, S . This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Caries prevalence; DMFT index; Water fluoride level; Semnan province; Garmsar; Iran

Abstract

Background: Among all health issues, oral health is the first issue. This important matter, is now more pronounced in childhood, and is of significance concern to the Ministry of Health, Department of Education is also involved. DMFT index (decayed, missing, filled teeth) is the most important quantitative criterion for measuring tooth health. Objectives: The purpose of this study was to determine DMFT index in 9 - 12 year old students in Garmsar City and factors affecting their caries status and also to determine fluoride concentrations in drinking water in the studied area.

Methods: In this descriptive and cross-sectional study, 500 students (260 girls and 240 boys) were randomly selected from public schools to assess the DMFT index. Clinical examination for diagnosis of caries was performed based on WHO criteria. Examination of subjects was conducted in the classroom and under the light of the flashlight using the catheter and mirror of the dentistry. The data were collected by a dentist after an interview and clinical examination. A questionnaire concerning socio-demographic characteristics, oral health and dietary habits was filled out. Drinking water fluoride concentration was measured in 144 samples collected from 12 water supplies using the SPADNS method. Data was analyzed using SPSS 18 software and presented as mean ± SD.

Results: The mean DMFT was 2.63 ± 2.39 (boys 3.25 and girls 2.22). The mean number of decayed, filled, missing teeth was 3.19 ± 2.34, 1.66 ± 0.83 and1.7 ± 0.95, respectively. Of the subjects surveyed, 20% were healthy. The difference between the DMFT index and its component D was significant with gender, but was not significant in components M and F. The mean fluoride concentration of the drinking water was 0.67 ± 0.14 mg/L, which is less than the normal range (1 mg/L). There is significant relationship between dental caries and father job (P value < 0.008) and mother education (P value < 0.001), economic condition of families (P value < 0.000), snacks and sweets consumption (P value < 0.005) mouthwash frequency and brushing (P value < 0.05) with number of decay teeth.

Conclusions: The prevalence of dental caries in 9 - 12 year old students in Garmsar is higher than the World Health Organization (WHO) index. So, it is necessary to improve the existing dental services and to carry out preventive programs for students in the future. The primary public health measure for reducing oral infectious disease, from a dental perspective, is the use of topical fluorides (as toothpastes) and water fluoridation at appropriate levels of intake. The primary public health measure, from a nutrition perspective, is dietary balance and moderation in the adherence to dietary guidelines, food guides, and dietary reference intakes.

Introduction

Despite great improvements in the oro-dental health of populations in several countries, global problems still persist and this imposes a heavy cost on the community (Peterson et al. 2005). According to the United States Surgeon General’s report, dental caries is stated to be the most common chronic childhood disease of children aged 5 to 17 years (Bagramian, et al. 2009). And according to reports of the Ministry of Health, Treatment and Medical Education, the prevalence of dental caries among elementary students is 68% because they represented those children receiving the benefits of systematic fluoride during tooth formation (Bazrafshan, et al. 2012). Recent studies have reported alarming high caries prevalence in Iran primary school children (Dobaradaran, et al. 2008; Rahmani, et al. 2010). Factors that have reduced dental caries, including the use of; systemic and topical fluorides, fluoride drops, tablets, gels, mouth rinses, and toothpastes, sealants, oral health education and dental care, improvements in diet (Clovis, J., et al. 1988; Heller, K.E., et al. 1997; Petersen, P.E. 2003). Furthermore, processed beverages and foods, which are distributed widely in fluoridated and non-fluoridated communities, now can contain substantial amounts of fluoride due to the use of fluoridated water in their production. When fluoride was first added to public water supplies for the purpose of controlling dental decay, fluoride-containing drinking water was the only significant source of fluoride exposure (Heller, K.E., et al. 1997). Fluoride in drinking water is usually the main source of fluoride intake, but consumption less or more than the permissible level of fluoride can cause a wide range of adverse health effects (Rahmani, et al. 2010). In higher concentration fluoride stimulates osteoblast activity leading to an increase in concellous bone mass. Excessive fluoride results in pathological changes in teeth and bones and small amounts (Mahvi, A., et al. 2006). Small amounts, in order of 1 mg/l in ingested water, are generally conceded to have a beneficial effect on the rate of occurrence of dental caries, particularly among children (Smith, G.E. 1985; Mahvi, A., et al. 2006). The presence of fluoride in drinking water has been related to dental caries and fluorosis since the early studies carried out by eager, as highlighted by dean, until now (Mahvi, A., et al. 2006). The ‘optimal’ fluoride level in drinking water is in the 0.7 - 1.2 mg/l for temperatures between 50 and 90.0F (World Health Organization, 1994; Peres, S.H., et al. 2003). The optimal concentration of fluoride in drinking water was based on the investigations by Dean who established that water fluoride concentrations near 1 ppm produce the best balance of substantial caries reduction with low prevalence of dental fluorosis (Dean, H.T., et al. 1941). The dental caries was registered with the use of the decayed, missing, filled teeth (DMFT) indexes (Allolio, B., et al. 1999; Cypriano, S., et al. 2005). Many studies have shown that low concentrations of fluoride in consumed drinking water can help to increase the DMFT index among students (Mahvi, A., et al. 2006; Rahmani, et al. 2010; Bazrafshan, et al. 2012). Dental caries is a multifactorial disease associated with a complex causal chain, which involves the physical chemical and microbiological composition of the dental biofilm, behavioral factors related to patterns of food intake and oral hygiene, and the socioeconomic background in which children and teenagers live (Mello, T., et al. 2008). The purpose of the present study was to determine the fluoride level in water supplies of Garmsar city in Semnan province and to compare it with standard values and measure the prevalence and severity of DMFT index in students 7 - 12 years old of the city of Garmsar, Semnan, (Iran) and to assess socioeconomic and behavioral covariates of dental caries experience. The findings from this study may be useful for preparing control strategy to improve the oral health conditions of primary school students in this area.

Materials and Methods

Study area

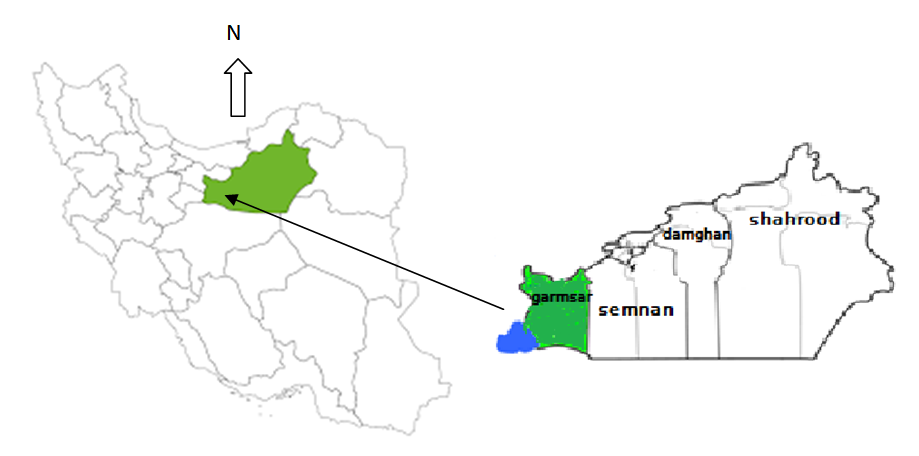

Garmsar is a city in Semnan Province, Iran. It lies at 34؛28‘N - 34؛30‘N latitude and 51؛52‘E - 52؛55‘E longitude, and altitude of 1170 m. The totalgeographical area of thedistrict is 10686 Km2, and it has a population of 48672 making it the 4th biggest city in Semnan. The climateis hot and dry in summer and mild in winter with an average yearly temperature 17.4°C and the average annual rainfall is 100 mm (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Location of the study area.

Research design

A cross-sectional descriptive study was performed from December 2016 to July 2017 among primary schools of Garmsar, Semnan Province, Iran. The list of all public schools that included the third to sixth grades (9 - 12 year-old) was obtained from the Department of Statistics and Planning at the General Directorate of Education in Garmsar District. A total of 50 public schools formed the sampling frame. Respecting the number of students of different classes, the share of each class in each school was determined using systematic random sampling. Thus, of these 50 schools, 10 Single schools and 10 mixed schools were randomly selected and incorporated in this cross-sectional study. Overall, 500 school children were included in this study. The aim was to assess the permanent teeth status respecting DMFT index and fluorosis rate and fluoride content in drinking water sources in Garmsar city.

Examination and Experiments

Our experts from the parents/ guardians of all participants involved in study that were less than 18 years of age, received verbal consent. The DMFT index was determined by the dentist examination. The children were examined for oral hygiene status, missing and dental caries while seated on a chair beside the classroom’s windows utilizing day light and room artificial light. Decayed and filled teeth were diagnosed by visual examination using a probe and dental mirror utilizing the criteria recommended by the World Health Organization (1994). The fluoride concentration in water was measured in 144 samples collected from 12 water supplies during one year, using the SPADNS method (Association, A.P.H., et al. 1915), with a DR/5000s Spectrophotometer (HACH Company, USA). The intensity prevalence and DMFT were determined in the samples and its real rate (confidence Interval) with 95% probability was estimated in the population and the role of sex on DMFT prevalence was assessed. On the other hand the fluoride influence on DMFT was calculated and was judged using paired t test and t-Tests statistically. Linear regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between the F concentrations in the drinking water with caries in permanent teeth (Dt).

Questionnaire

After the physical examinations a special questionnaire was completed for students. In this cross-sectional descriptive study, 250 samples of girl and boy 9 - 12 year-old schools were randomly collected. The questionnaire included socio-demographic data related to age, children’s personal hygienic practices (e.g. brushing intervals, mouthwash), nutritional factors contributing to tooth decay (e.g. consumption of seafood, tea and nuts) and socio-economical status.

Data Entry and Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed by SPSS software version 18 under Windows 7, by using statistical tests including paired t Test and t-Tests to determine the degree of association between DMFT index with fluoride rates and factors involving with dental caries. Linear regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between the F concentrations in the drinking water with caries in permanent teeth (Dt). P-values of < 0.05 were considered indicative of a statistically significant difference. Data analysis of the questionnaire was performed using the software SPSS, Chi-Square and One Way Anova tests were used. The level of statistical significance for all tests was set at P < 0.05.

Results

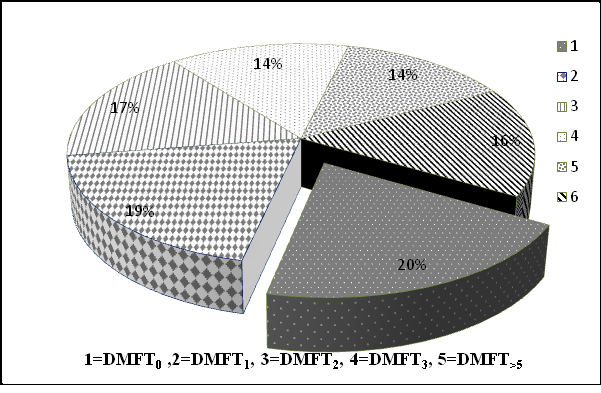

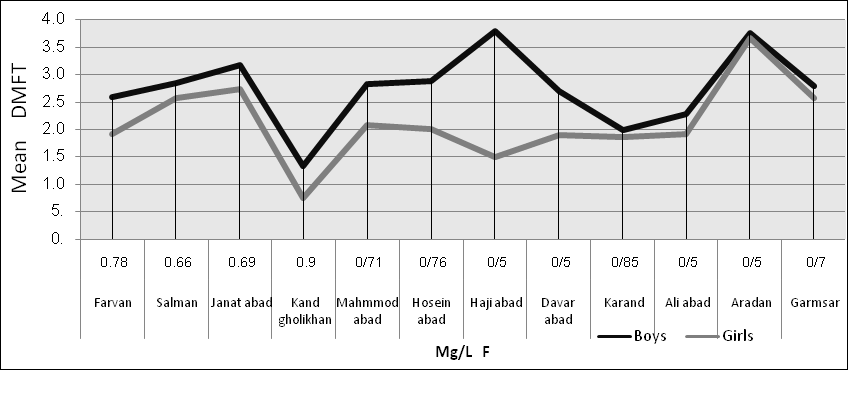

The total number of participants in this study was 500. Of these, 240 (48%) were males and 260(52%) were females. The students’ DMFT status has been presented in Table 1 according to DMF intensity and tooth number and sex. The mean DMFT values were 2.22 ± 2.21 and 3.25 ± 2.55 in the boys and girls respectively and the total was 2.63 ± 2.42. The results show that the DMFT index was higher in the boys than in the girls and this difference was statistically significant (P < 0.01). Also, the mean DT values in boys and girls was significantly different but the mean MT and FT values in boys and girls had not significant difference. The frequency distribution of DMFT and decayed (DT), missing (MT) or filled teeth (FT) among the sample population is shown in Figure 2 and Table 2. Also, according to the results of this study, 20% of the sample population was caries-free. However, approximately 13 – 14% of these school children had either MT or FT. The frequency of school children with DMFT equal one or two was between 19% and 17%, while that with DMFT more than five teeth was 16%. The water fluoride concentration was determined from 12 water supplies including 2 urban area and 10 rural. The mean fluoride concentration was 0.67 ± 0.14 ppm (table 3), ranging from 0.5 to 0.96 pprn. The mean fluoride concentration was less than the standard limiting (0.7 - 1.2 ppm) and approximately in six of the water supplies was in the range of standard limit (Table 3). Also Table 3 demonstrate that the proportion of caries-free subjects increased with increasing fluoride concentration in water (P < 0.01). Figure.3 demonstrates that mean DMFT scores decreased with increasing water fluoride levels from ~ 0.7 pprn F to .9 pprn F, and then increased at < 0.6 ppm F. The results of the questionnaire showed that 5% of the students brushed their teeth twice or more a day, 25% once a day, 47% Three days a week and 23% didn’t use a tooth-brush at all. Also in terms of drinking tea, 67% of the students were drinking tea at least once a day, 21% twice or more a day and 12% didn’t drink tea. 40% of students consumed sea foods, including fish, at least once a month.

Table 1: DMFT a Index Among 9 - 12 Year Old Students According to Gender.

| Index Gender | No. | DTa | MTa | FTa | DMF Index * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | 260 | 2.96±2.11 (82.98%) |

1.88±1.05 (1.8%) |

1.7±0.82 (4.94%) |

2.22±2.21 |

| Boys | 240 | 3.36±2.49 (55.83%) |

1.6±0.91 (8%) |

1.58±0.87 (10.08) |

3.25±2.55 |

| Total | 500 | 3.19±2.34 (68.84%) |

1.7±0.95 (4.8%) |

1.66±0.83 (7.48%) |

2.63±2.39 |

| Diffrence rate between the sexes | P<0/03 | **N.S | **N.S | P<0/01 | |

aAbbreviations: D, Decayed; M, Missing; FT, Filled Teeth

*Mean ± SD

**Ns= statistically non-significant diffrence

Table 2: DMFT Index among 9 - 12 Year Old Students According to Age.

| Age, y | No. | D a | M a | F a | D+M+F | *DMFT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 125 | 288 | 16 | 23 | 327 | 2.51±2.00 |

| 10 | 125 | 377 | 7 | 6 | 390 | 2.97±2.43 |

| 11 | 125 | 397 | 7 | 16 | 420 | 3.33±2.87 |

| 12 | 125 | 272 | 11 | 20 | 303 | 2.54±2.28 |

| Total | 500 | 1334 | 41 | 65 | 1440 | 2.83±2.39 |

aAbbreviations: D, Decayed; M, Missing; FT, Filled Teeth

*Mean ± SD

Table 3: Distribution and Mean of Dt Scores by Water Fluoride Status in Regions studied.

| Regions | Mean F (mg/l) | Dental caries measures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls Dt | Boys Dt | Dt | |||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | ||

| Farvan | 0/78 | 2.09 | 0.368 | 3.62 | 0.625 | 2.73 | 0.373 |

| Salman | 0/66 | 2.9 | 0.674 | 3.14 | 0.85 | 3 | 0.514 |

| Janatabad | 0/69 | 2.8 | 0.489 | 3.666 | 1.45 | 3 | 0.480 |

| Kand gholikhan | 0/9 | 1.6 | 0.221 | 3 | 1 | 1.9 | 0.270 |

| Mahmmodabad | 0/71 | 2.5 | 0.428 | 3.33 | 1.20 | 2.81 | 0.510 |

| Hoseinabad | 0/76 | 2.83 | 0.489 | 2 | 0.408 | 2.64 | 0.439 |

| Hajiabad | 0/5 | 4.11 | 1.08 | 3.66 | 0.333 | 3.7 | 0.866 |

| Davar bad | 0/5 | 3.25 | 0.428 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 2.93 | 0.359 |

| Karand | 0/85 | 2.143 | 0.34 | 2.08 | 0.333 | 2 | 0.258 |

| Aliabad | 0/5 | 2 | 0.258 | 2.5 | 0.957 | 2.14 | 0.311 |

| Aradan | 0/5 | 4.3 | 0.380 | 4.96 | 0.524 | 4.81 | 0.384 |

| Garmsar | 0/7 | 3.9 | 0.220 | 3.637 | 0.313 | 3.8 | 0.180 |

| *Total | 0.67 ± 0.14 | *3.17 | 0.436 | ||||

| *Mean ± SD, **paired t test(p < 0.01) | |||||||

Figure 2: Distribution of school children girls and boys at 9 - 12 years old according to the DMFT index in Garmsar city.

In the present study, there was a higher rate of dental caries in students whose educational levels of mother’s were elementary and illiterate whereas there was no significant association between educational levels of father’s and infestation (P > 0.05). The students whose mothers were occupied had higher dental caries (P > 0.05). A dynamic relation exists between sugars and oral health. There was significant relationship between the intervals of snacks and sweets consumption and economic condition of families with number of decay teeth. (P = 0.000, 0.005, 0.000 respectively).

Based on the results of Table 4, the relationship between the dental caries and the frequency of brushing was also the opposite. In addition to brushing, the effect of using fluoride mouthwash, junk food, fish and tea can be one of the reasons that have a major role in increasing the DMFT index.

Table 4: The prevalence of dental caries based on demographic characteristics, oral hygiene habits and dietary habits.

| Variables | No. of Non - caries n (%) |

% | No. of with caries/ total n (%) |

Prevalence (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner of school | Governmental | |||||

| Father’s job | General employee | 47 | 73.4 | 17/64 | 26.6 | P<0.008 |

| Company employee | 80 | 60.2 | 53/133 | 39.8 | ||

| Farmer | 8 | 61.5 | 5/13 | 38.5 | ||

| self-employed | 11 | 34.4 | 21/32 | 65.6 | ||

| Unemployed | 5 | 62.5 | 3/8 | 37.5 | ||

| Mother’s job | Housekeeper | 108 | 69.7 | 47/155 | 30.3 | P<0.288 |

| Employed | 60 | 63.2 | 35/95 | 36.8 | ||

| Father’s education | Primary-Guidance | 48 | 57.83 | 35/83 | 42.16 | P<0.118 |

| High school or diploma | 39 | 40.62 | 57/96 | 59.37 | ||

| University education | 32 | 53.33 | 28/60 | 46.66 | ||

| Illiterate | 7 | 63.63 | 4/11 | 36.36 | ||

| Mother’s education | Primary -Guidance | 45 | 37.2 | 76/121 | 62.8 | P<0.001 |

| High school or diploma | 30 | 60 | 20/50 | 40 | ||

| University | 41 | 62.1 | 25/66 | 37.9 | ||

| Illiterate | 6 | 46.2 | 7/13 | 53.8 | ||

| Brushing intervals | once per day | 18 | 26.86 | 49/67 | 73.13 | P<0.000 |

| twice per day | 35 | 37.2 | 59/94 | 62.8 | ||

| three times per day | 45 | 70.31 | 19/64 | 29.68 | ||

| None | 6 | 24 | 19/25 | 76 | ||

| Mouthwash intervals | once a week | 44 | 38.9 | 69/113 | 61.1 | P<0.05 |

| twice a week | 18 | 40 | 27/45 | 60 | ||

| three times per day | 16 | 66.66 | 8/24 | 33.33 | ||

| None | 25 | 36.76 | 43/68 | 63.23 | ||

| consumption of Snack | Low | 35 | 60.3 | 23/58 | 39.7 | P<0.000 |

| Average | 16 | 27.1 | 43/59 | 72.9 | ||

| Much | 34 | 27.6 | 89/123 | 72.4 | ||

| None | 7 | 70 | 3/10 | 30 | ||

| consumption of sugar and sweets |

Low | 70 | 61.9 | 43/113 | 38.1 | P<0.005 |

| Average | 38 | 44.2 | 48/86 | 55.8 | ||

| Much | 16 | 38.1 | 26/42 | 61.9 | ||

| None | 2 | 22.2 | 7/9 | 77.8 | ||

| consumption of Seafood | Once a month | 98 | 58.7 | 69/167 | 41.3 | P<0.097 |

| Twice a month | 17 | 60.7 | 11/28 | 39.3 | ||

| Three times a month | 11 | 57.89 | 8/19 | 42.1 | ||

| None | 14 | 38.9 | 22/36 | 61.1 | ||

| Family income($/month) | Less than $ 400 | 22 | 61.1 | 14/36 | 38.9 | P<0.000 |

| Between$ 400 to $ 650 | 86 | 54.1 | 73/159 | 45.9 | ||

| More than $ 650 | 48 | 87.3 | 7/55 | 12.7 | ||

Discussion

The present study has provided useful base line data dental caries prevalence and relation to various water fluoride concentration levels among primary school students in Garmsar areas of province Semnan. The survey of this study showed that mean DMFT values in boys (3.25) was higher than in girls (2.22). In consistent, Bazrafshan et al. had reported the mean DMFT value was 2.41 ± 2.12, which was higher in the boys (2. 68 ± 2.15) in comparison with the girls (2. 13 ± 1.91) in Zahedan City, Iran (Bazrafshan, et al. 2012) and in contrast Mahvi et al. (2006) had reported the DMFT prevalence to be 1.48 ± 0.13 in 12 year old students in the town of Behshahr and also that the DMFT value was higher in girls than in boys. On the other hand, Aldosarie et al in their study of selected urban and rural populations in Qaseem region reported a mean DMFT score was 4.53 ± 3.57, which was higher in the boys (5.05 ± 3.97) in comparison with the girls (4. 03 ± 3.08) and also in Riyadh regions reported a mean DMFT score was 5.06 ± 3.65, which was higher in the boys (5.72 ± 3.85) in comparison with the girls (4.47 ± 3.35) (Aldosari, A., et al. 2004). In Mexico, Irigoyen et al. examined a total of 2275 school children 12 yr of age from the four health regions for the prevalence and severity of dental caries. The proportion of caries-free children was only 10%, and the DMFS index was 6.94. 78% of the index derived from decayed surfaces, and 19% from filled surfaces (Irigoyen, M., et al. 1994). In western Nepal, the caries prevalence and mean DMFT score of 12 - 13-year-olds was 41 % and 1.1 (urban 35% and 0.9; rural 54% and 1.5) (Yee, R., et al. 2002). El-Qaderi et al. reported about one-quarter (24%) of schoolchildren were caries-free while 16 – 8% of them had missing or filled teeth with a DMFT of 3.13 ± 2.45 (El-Qaderi, S., et al. 2006). As mentioned earlier the mean DMFT score in the study areas was 2.63 ± 2.42 that boys had significant lower missing (MT) or filled teeth (FT) but significantly tooth decay scores higher than girls (P < 0.001). According to the results of the present study, the mean DMFT scores in 9 - 12 years old students are higher than the global standards suggested by WHO references and this is perhaps due to the lack of fluoride in people’s consumption of resources. In all of the above mentioned studies, a direct relation between water fluoride concentration and DMFT and fluorosis prevalence has been observed. It can be assumed that low concentrations and high of fluoride in drinking water can increase the rate of DMFT incidence and fluorosis in children. In the regions of Dayer and Larestan, Ramezani, et al. (2004) found that the concentration of fluoride in drinking water is higher than permitted limit and fluorosis prevalence is high. Exposure to fluoride higher than permitted limit was associated with higher fluorosis prevalence and Dental fluorosis is the most common effect of high water fluoride concentration. Bazrafshan has reported, the mean fluoride concentration in 144 samples from different sources in Zahedan city was 0.57 ± 0. 07 mg/L, that is less than the guidelines set by WHO (1.5 mg/L) and according to the results of this study, the DMFT scores in 8 - 12 year old students are higher than the global standards suggested by WHO[3]. In the present study, the mean fluoride concentration in some areas, considering the high temperature of the environment seems to be far less than the guidelines set by WHO (figure 3). As seen in Figure 3, the concentration of F in the study area source water was found to low widely from 0.5 to 0.9 mg/L. Dobaradaran, S., et al. (2009), has reported, the concentration of F in the village water was from 0.99 to 2.50 mg/L and in other studies in Iran the F level in the groundwater ranged from 0.12 to 0.39 mg/L in one area and 0.12 to 2.17 mg/L in another. In Table 3, the Dt in the 2 urban regions and 10 rural is seen to range between 1.83 and 4.81. Linear regression analysis indicates there is significant correlation between the F content of the water with Dt in these 12 regions. For example in Aradan, with 0.50 mgF/l in its drinking water is a mean Dt = 4.81 and K and, with 0.9 mgF/l is a mean Dt =1.83. Thus, over the fairly narrow F concentration range in this study, it appears there is a direct linear correlation between the F content of drinking water and dental caries in both the boys and girls sex especially in the boys. Ekanayake, et al. (2002), examined a total of 518 14-year-old children who were lifelong residents in Sri Lanka for dental caries and developmental defects of enamel. In conclusion, the relationship that was observed in this study between fluoride levels in drinking water, diffuse opacities and caries suggests that the appropriate level of fluoride in drinking water for arid areas of Sri Lanka is around 0.3 mg/l. Nasehinia et al. (2004) reported the mean concentration of fluoride in water supplies of Damaghan city was measured in low rain seasons 0.37 mg/l and high rain seasons 0.6 mg/l the DMF index for 12 years old student was equal 2.00 that comparing these data with the WHO classify action for DMF index, showed them to be considered in the second surface (low) classification. The content of fluoride in the village groundwater in Arsanjan, Iran was found to vary from 1.2 to 0.10 mg/l. In Saudi Arabia, Aldosari et al. (2004), found that there was statistically significant (p < 0.05) difference in mean dmft scores at various fluoride levels with lowest dmft scores at the optimum water fluoride level (0.61 – 0.80 ppm) and highest at two extremes i.e. 0.0 to 0.3 ppm and > 2.5 ppm among the primary schoolchildren, while in intermediate schoolchildren no significant difference in overall mean DMFT scores of children at various water fluoride levels could be found. Furthermore, Bazrafshan et al. (2012) had reported that the highest dental caries was in the age group of 8 to 9 years old. Our study in Garmsar city has shown that the prevalence of DMFT caries is highest among school children aged 1011 years of age. The results of the present study indicate that according to factors such as oral hygiene habits, dietary habits of the population, Climatic conditions, socioeconomic, cultural, fluoride exposures also need to be considered. Furthermore, it’s imperative that each country and even any city calculates its own optimal level of fluoride in drinking water in accordance to the dose–response relationship of fluoride in drinking water with the levels of caries and fluorosis. In this study, there was significant relationship between dental caries with mothers’ education level, fathers’ occupation, and economic status. Therefore the dental caries were significantly higher in students whose fathers were farmer (P < 0.008). This study also revealed that students in families with low economic status were definitely in a higher position in terms of having dental caries relative to higher income families. In agreement with the present results, Faezi et al. (2012) had reported, a significant association there was between dental caries and parents’ education level. Our study also showed significant association between the accesses to brushing intervals per day, mouth wash intervals and dental caries rate. In the study of Guadagni (2005) and Taani (2003) There was a significant relationship between the frequency of brushing and DMFT. In the study of Nematollahi and Sorkhi (2001) in Mashhad, the children whose parents (especially mother) had attained a higher education level had lower dmft scores. As seen in the results, the frequency of the use of food groups such as sugar and sugar and sweets is one of the effective factors in the number of decayed teeth. These results are consistent with the results of many studies (Beighton, D., et al. 1996; Nematollahi, H., et al. 2001). In our study, snack foods are low-value foods for the body that do not have enough nutrients, so they should be taken with caution. The results of this study showed that 1.2% of people with dental caries did not eat snacks and 56% of them consumed the high amount of snacks. But the relationship between consumption of seafood and number of decay teeth was not significant. The primary public health measure for reducing oral infectious disease, from a dental perspective, is the use of topical fluorides (as toothpastes) and water fluoridation at appropriate levels of intake. The primary public health measure, from a nutrition perspective, is dietary balance and moderation in the adherence to dietary guidelines, food guides, and dietary reference intakes (Touger-Decker, et al. 2003).

Figure 3: Distribution DMFT Index among 9 - 12 years old students of primary schools according to water fluoride concentration levels in urban and rural areas.

Conclusion

The results of the study indicate that, the concentration of fluoride ion in all water sources varies from place to place. These results may arise due to the nature of rock and soil formation. Furthermore, the results of the present study indicate that according to factors such as oral hygiene habits, dietary habits of the population, Climatic conditions, socioeconomic, cultural, fluoride exposures also need to be considered. Finally, it’s imperative that each country and even any city calculates its own optimal level of fluoride in drinking water in accordance to the dose–response relationship of fluoride in drinking water with the levels of caries and fluorosis.

Declarations

Acknowledgements: We want to express our special appreciation of Semnan University of Medical Sciences for cooperation and providing facilities to this work. Grate full thanks of all the staff and students of primary schools of Garmsar, Dr. Bahram Ghods, Engineer Yasaman Ghafari, Engineer kazemi and Engineer Molai for their cooperation in this study. Special thanks to my husband, Engineer Saeed Purshahrab, for her help, encouragement and patience.

Funding: This study has been supported by Semnan University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, semnan, Iran

Availability of data and materials: All the necessary data have been given in the paper. If other investigators need our data for their works, they can contact with first author through the email.

Authors’ contributions: All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Our experts from the parents/ guardians of all participants involved in study that were less than 18 years of age received verbal consent.

Consent for publication: Not applicable

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

1. Allolio, B., Lehmann, R. Drinking water fluoridation and bone.(1999) Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 107(1): 12-20.

2. Al Dosari, A.M., Wyne, A.H., Akpata, E.S., et al. Caries prevalence and its relation to water fluoride levels among schoolchildren in Central Province of Saudi Arabia. (2004) Int Dent J 54(6): 424-428.

3. Association, A.P.H., et al. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. Vol. 2. 1915: American Public Health Association.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

4. Bagramian, R.A., Garcia-Godoy, F., Volpe, A.R. The global increase in dental caries. A pending public health crisis. (2009) Am J Dent 22(1): 3-8.

5. Bazrafshan, E., Kamani, H., Mostafapour, F.K., et al., Determination of the decayed, missing, filled teeth index in Iranian students: a case study of Zahedan city. (2012) J Health Scope 1: 84-88.

6. Beighton, D., Adamson, A., Rugg-Gunn, A. Associations between dietary intake, dental caries experience and salivary bacterial levels in 12-year-old English schoolchildren. (1996) Arch Oral Biol 41(3): 271-280.

7. Clovis, J., Hargreaves, J.A. Fluoride intake from beverage consumption. (1988) Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 16(1): 11-15.

8. Cypriano, S., de Sousa Mda, L., Wada, R.S. Evaluation of simplified DMFT indices in epidemiological surveys of dental caries. (2005) Rev Saude Publica 39(2): 285-292.

9. Dean, H.T., Jay, P., Arnold, F.A., et al. Domestic water and dental caries: ii. a study of 2,832 white children, aged 12-14 years, of 8 suburban chicago communities, including lactobacillus acidophilus studies of 1,761 children. (1941) Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 56(15): 761-792.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

10. Dobaradaran, S., Mahvi, A.H., Dehdashti, S., et al. Correlation of fluoride with some inorganic constituents in groundwater of Dashtestan, Iran. (2009) Fluoride 42(1): 50-53.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

11. Dobaradaran, S., Mahvi, A.H., Dehdashti, S., et al. Drinking water fluoride and child dental caries in Dashtestan, Iran. (2008) Fluoride 41(3): 220-226.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

12. Ekanayake, L., van der Hoek, W. Dental caries and developmental defects of enamel in relation to fluoride levels in drinking water in an arid area of Sri Lanka. (2002) Caries Res 36(6): 398-404.

13. El-Qaderi, S.S., Quteish Ta’ani, D. Dental plaque, caries prevalence and gingival conditions of 14–15-year-old schoolchildren in Jerash District, Jordan. (2006) Int J Dent Hyg 4(3): 150-153.

14. Faezi, M., Farhadi, S., NikKerdar, H. Correlation between dmft, diet and social factors in primary school children of Tehran-Iran in 2009-2010. (2012) J Mashhad Dental School 36(2): 141-148.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

15. Guadagni, M.G., Cocchi, S., Tagariello, T., et al. Caries and adolescents. (2005) Minerva stomatologica 54(10): 541-550.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

16. Heller, K.E., Eklund, S.A., Burt, B.A. Dental caries and dental fluorosis at varying water fluoride concentrations. (1997) J Public Health Dent 57(3): 136-143.

17. Irigoyen, M., Szpunar, S. Dental caries status of 12-year-old students in the State of Mexico. (1994) Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 22(5 Pt 1): 311-314.

18. Mahvi, A., Zazoli, M.A., Younecian, M., et al. Survey of fluoride concentration in drinking water sources and prevalence of DMFT in the 12 years old students in Behshar City. (2006) J Med Sci 6(4): 658-661.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

19. Mello, T., Antunes, J., Waldman, E., et al. Prevalence and severity of dental caries in schoolchildren of Porto, Portugal. (2008) Community Dent Health 25(2): 119-125.

20. Nasehinia, H., Naseri, S. A survey of fluoride dosage in drinking water and DMF index in Damghan city. (2004) Water and Wastewater 15(49): 70-72.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

21. Nematollahi, H., KhordiMood, M. A study of relationship between dental caries experience of 6-36 month old children and dental caries experience & socioeconomic status of their mothers in Mashhad. (2001) J Mash Dent Sch 25(1): 2.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

22. Peres, S.H., Peres, A.S., Ramires, I., et al. Does the interruption of water fluoridation supply increase dental caries prevalence? (2003) Braz J Oral Sci 2(4): 169-173. (libdigi.unicamp.br/document/?down=3783)

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

23. Petersen, P.E. The World Oral Health Report 2003: Continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century–the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. (2003) Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 31(Suppl 1): 3-23.

24. Petersen, P.E., Bourgeois, D., Ogawa, H., et al. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. (2005) Bull World Health Organ 83(9): 661-669.

25. Rahmani, A., Rahmani, K., Dobaradaran, S., et al., Child dental caries in relation to fluoride and some inorganic constituents in drinking water in Arsanjan, Iran. (2010) Fluoride 43(3): 179-186.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

26. Ramezani, G.H., Valaei, N., Eikani, H. Prevalence of DMFT and fluorosis in the students of Dayer city (Iran). (2004) J Indian Soc Pedo Prev Dent 22(2): 49-53.

27. Smith, G.E. Fluoride and bone: an unusual hypothesis. (1985) Xenobiotica 15(3): 177-186.

28. Taani, D.S., al-Wahadni, A.M., al-Omari, M. The effect of frequency of toothbrushing on oral health of 14-16 year olds. (2003) J Ir Dent Assoc 49(1): 15-20.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

29. Touger-Decker, R., Van Loveren, C. Sugars and dental caries. (2003) Am J Clin Nutr 78(4): 881S-892S.

30. World Health Organization. Fluorides and oral health: Report of a WHO Expert Committee on Oral Health Status and Fluoride Use. (1994) World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 846: 1-37.

PubMed||CrossRef||Others

31. Yee, R., McDonald, N. Caries experience of 5–6-year-old and 12–13-year-old schoolchildren in central and western Nepal. (2002) Int Dental J 52(6): 453-460.