Synthesis and characterization of Ursolic acid loaded poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles and Caffiene loaded poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles in colorectal cancer cell line

Jose Merlin, J.P1*, Venkadesh, B2, Sheeja S Rajan3

Affiliation

- 1PG & Research Department of Zoology, Muslim Arts College, Thiruvithancode, Tamilnadu, India

- 2PG & Research Department of Zoology, Government Nandanam Arts College Chennai, Tamilnadu, India

- 3Department of Biochemistry, Theivanai Ammal College for Women Villupuram, Tamilnadu, India

Corresponding Author

Jose Merlin, J.P, PG & Research Department of Zoology, Muslim Arts College Thiruvithancode - 629 174, Tamilnadu, India, Tel: +91 9442094520; E-mail: jose4bio87@gmail.com

Citation

Jose Merlin, J.P. Synthesis and Characterization of Ursolic Acid Loaded Poly (Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) Nanoparticles and Caffiene Loaded Poly (Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) Nanoparticles in Colorectal Cancer Cell Line. (2018) J Nanotechnol Material Sci 5(1):1- 7

Copy rights

© 2018 Jose Merlin, J.P This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Nanoparticles, Anticancer, Ursolic acid (UA), Caffeine (Caf), Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA)

Abstract

The aim of the present study was to develop UA-PLGA NPs and Caf -PLGA NPs to study its anticancer efficacy in colorectal cells in vitro. The method used for the study was to synthesis the nanoparticles, Particle size, size distribution and zeta potential, Drug encapsulation efficiency and in vitro drug release. Then the nanoparticles were subjected in cancer cell lines and the parameters used were Drug treatment and dose fixation study, Apoptotic morphological changes. The results indicate that the chemo sensitization of drug loaded nanoparticles demonstrated increased anticancer property in cancer cells than UA-PLGA NPs and Caf - PLGA NPs treatment alone.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the fourth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death. About 96,830 new cases of colon cancer and approximately 40,000 cases of rectal cancer will occur and 50,310 people will die of colon and rectal cancer combined[1]. The long term survival rate of colon cancer patients treated by conventional modalities such as surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy remains far from satisfactory[2]. Colon cancer cells are only the modestly responsive or even nonresponsive to the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapeutic agents[3].

The term “chemo sensitization” was originally introduced as a strategy to counter the development of resistance in tumor cells to anticancer chemotherapeutic agents. Simply put, chemo sensitization in cancer therapy involves use of a chemical that renders cancer cells more sensitive to a chemotherapeutic agent. Development of resistance in cancer cells to anticancer drugs involved mutations in target genes, up-regulation or over-expression of genes control- ling efflux pumps, production of enzymes that “detoxified” the drugs, and DNA repair[4].

Ursolic acid, a pentacyclic tri terpenoid carboxylic acid found in plants, has various biological properties, including anti-inflammatory, anticancer, anti-angiogenic, and anti-oxidative activities[5,6] Numerous reports of UA’s in vitro activities against tumor cell lines have appeared in the literature[7] and the possible mechanisms of action have been reviewed recently[8].

Caffeine (1, 3, 7-trimethylxanthine) is found in both coffee and tea, so a great number of people are exposed to various doses of caffeine. It acts as a stimulant for the central nervous, respiratory and cardiac system. Caffeine significantly reduces cancer risk caused by environmental and dietary carcinogens[9] and the protective action of caffeine against a variety of chemical carcinogens was established by several studies, carried out by Abraham[10]. Because of purine nature it has a mutagenic potential. The mutagenic effect of caffeine was detected by Fries and Kihlman[11].

Nanotechnology has led to the development of drug delivery systems to achieve the targeted transport of anticancer drugs[12]. Incorporation of anticancer drugs into the nano particles, reduces the adverse reactions and increases the therapeutic efficacy due to changes in the pharmacokinetics or tissue distribution[13]. Nanoparticles may be delivered to specific sites by size dependant passive targeting or by active targeting[14,15]. The passive Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect is thought to occur in solid tumors. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) stimulates vascular endothelial cell growth, increases the permeability of tumor-associated neo vasculature, and causes leakage of circulating macromolecules and small particles into the tumor[16]. Since tumors lack an effective lymphatic drainage system to clear these extravagated substances macromolecules and nanoparticles that enter the tumor has been accumulated[17-19].

PLGA poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) is one of the most successfully used biodegradable nanosystem for the development of nano medicines because it undergoes hydrolysis in the body to produce the biodegradable metabolite monomers, lactic acid and glycolic acid[20]. PLGA have potential because of their size, hydrophobic core with hydrophilic periphery, and biocompatibility[21]. In order to minimize systemic toxicity and to improve therapeutic efficacy, in this study we encapsulated UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs and tested its anticancer potential in colon cancer cells in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Poly Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA) 65:35 (MW 40,000 - 75,000), Poly Vinyl Alcohol (PVA) (MW 25,000), Ursolic Acid (UA), Caffeine (Caf), Thio Barbituric Acid (TBA), Phenazine Metho Sulphate (PMS), Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT), 5, 5-Dithiobis 2-Nitrobenzoic Acid (DTNB), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT), Ethidium Bromide (EtBr), Acridine Orange (AO), Fetal Calf Serum (FCS), DMEM medium, glutamine- penicillin-streptomycin solution, ficoll-histopaque 1077, trypsin-EDTA were purchased from Sigma Chemicals Co., St. Louis, USA.

Preparation and characterization nanoparticles

Preparation of drug loaded nanoparticles

UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs were prepared by nano precipitation method as previously described by Peltonen, 2003[31]. 0.1% of PVA was prepared by dissolving 100 mg of PVA in 100 ml distilled water in magnetic stirrer at 60°C. Organic solution of PLGA (100 mg) and UA/Caf (10 mg) in acetone (10 ml) was added to PVA solution (10 ml). The sample was sonicated at 25 watts for 2 min (Sonics VC-130, Sonics and Materials Inc. CT, USA) and kept the sample under magnetic stirrer at room temperature for 6 h. To remove the non-incorporated drug, the obtained nano suspension was centrifuged and washed with distilled water twice at 14,000 rpm for 30 min. The supernatant containing the free drug was discarded and the pellet was freeze dried at -50°C.

Particle size, size distribution and zeta potential

DLS (Zetasizer Nano, Malvern Instruments Ltd. United Kingdom) was used to measure the average size and size distribution of the prepared nanoparticles. Three different batches were analyzed to give an average value and standard deviation for the particle diameter and zeta potential.

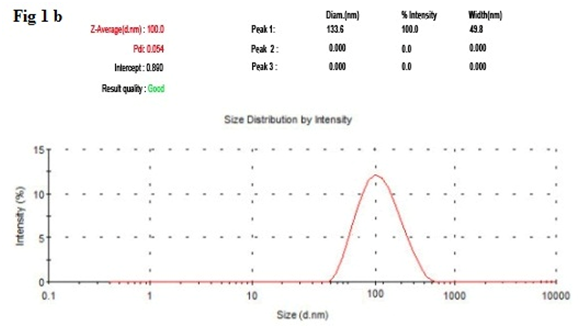

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The morphological features of RSV-GNPs were examined by scanning electron microscopy (Quanta 200F, FEI, Hillsboro or USA). The samples were sprinkled on to a double-sided tape and sputter-coated with a 5 nm thick gold layer. The inner-structure of nanoparticles was observed after fracturing by a razor blade.

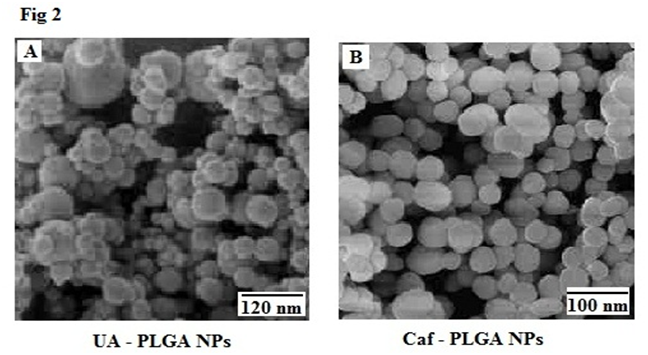

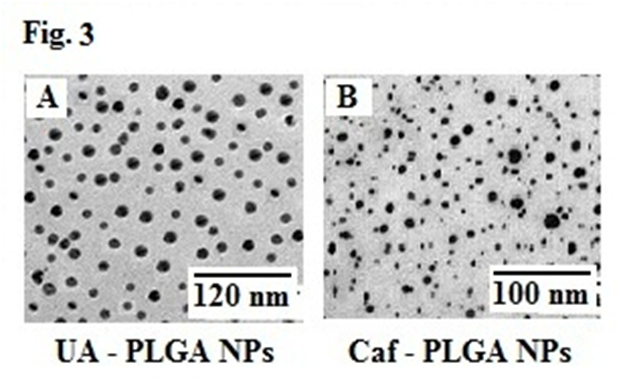

Transmission electron microscopy

A transmission electron microscope (CEM 902A; Zeiss, Germany) was used to observe the two-dimensional, relative size morphology of drug loaded nanoparticles. Nanoparticle suspensions were diluted in de-ionized water (1:100 vol/vol) and before observation nanoparticles were negatively stained with a solution of 1 % phosphotungstic acid.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Thermal properties of polymers and particles were measured by DSC. Nitrogen was used as the purge gas. Top pierced aluminum pans were used throughout the study with sample weights varied between 5 and 10 mg. The DSC system was controlled by DSC-Q-200-TA instruments USA, Built 79 software (version 23.10). Samples were characterized by DSC in the range of 25 – 360°C at a heating rate of 10°C per minute.

X-ray diffraction:

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) experiments were carried out using XRD instrument (X’ Pert PRO PAN analytical). 5 μg of the drug loaded nanoparticles powder was taken in the sample holder and XRD was recorded.

Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra of drug loaded nanoparticles were recorded using FTIR spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer Spectrum RXI). The characteristic peaks were recorded for each sample.

Drug encapsulation efficiency

Drug encapsulation efficiency was described by the method of Mathew, 2010[32]. UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 min. The supernatant containing unencapsulated drug was removed. The samples were washed with de-ionized water and the pellets obtained were re-suspended in de-ionized water and freeze dried for 48 h to get powdered sample. Three milliliters of the supernatant obtained after centrifugation was taken in a cuvette and the absorbance value was recorded at 266 nm using a UV spectrophotometer.

Encapsulation efficiency (%) = [Drug] tot − [Drug] free / [Drug] tot × 100

In vitro drug release

Drug release profiles of nanoparticles were investigated in PBS and 10 % FBS medium at pH 7.4 accordingly by the method of Dong, 2004[33]. Five microgram of lyophilized UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs were dispersed in 30 ml of 10% FBS/PBS and placed in water bath shaker set at 37°C with a shaking speed of 120 rpm. At 1h time intervals 3 ml of supernatant from the sample was taken for analysis and the same amount of fresh 10% FBS/PBS was replaced to the sample. Each time absorbance value at 266 nm was recorded using UV spectrophotometer.

[UA/Caf]rel

Drug release (%) = ----------------- x 100

[UA/Caf]tot

Analysis of drug loaded nanoparticles uptake by fluorescence microscopy:

The cellular uptake of UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs in HT29 cells was analyzed by the fluorescence microscopy[34]. In brief, cells were incubated with Hoechst 33258 dye (50 mg/mL; blue fluorescence) for 30 min, and then washed two times with PBS. The washed cells were re suspended in media and then incubated with RSV for 3 h. Cells were then examined under a fluorescence microscope (BX51; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and images were captured using a Photo metrics Cool- snap SHC-745 color camera (Samsung, Korea).

Anticancer efficacy of drug loaded nanoparticles

Cell lines and culture conditions

The present work was carried out in colon cancer cell lines (HT29). HT29 cells were obtained from National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India. The present work has been approved by Institutional Ethical Committee (IEC), Annamalai University. The cells were grown as monolayer in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator.

Drug treatment and dose fixation study

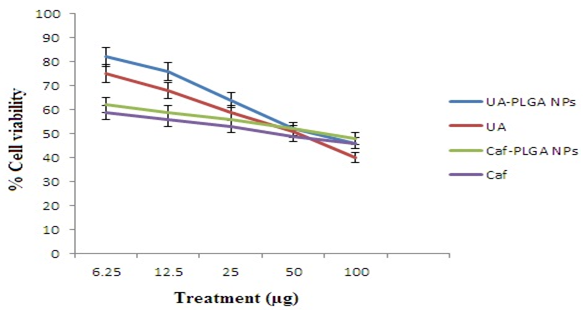

Cells were treated with different concentration of UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs (6.25, 12.5, 25, 50 and 100 μg) and incubated for 24 h at 5 % CO2 incubator. Cytotoxicity was observed by MTT assay by the method of Mosmann, 1983[35]. IC50 was calculated by (ED50 plus software V 1.0). IC50 values were calculated and the optimum dose was used for further study.

Experimental groups

The HT29 cells were divided into 4 experimental groups. Group 1: Untreated control cells, Group 2: UA-PLGA NPs treatment alone (88.10 μg), Group 3: Caf-PLGA NPs treatment alone (49.63 μg) and Group 4: UA-PLGA NPs (88.10 μg) + (after one hour) Caf-PLGA NPs (49.63 μg) treatment.

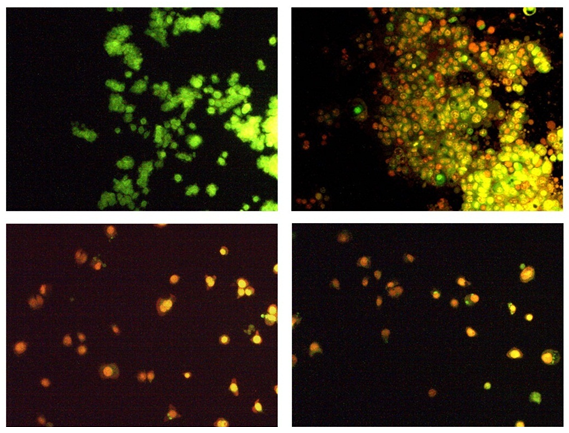

Apoptotic morphological changes

Apoptotic morphological changes during drug loaded nanoparticles treatment were analyzed by AO/EtBr staining. This dual staining method differentiates condensed chromatin of dead apoptotic cells from the intact normal cell nuclei (Lakshmi, 2008)[36].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA followed by DMRT taking p < 0.05 to test the significant difference between groups.

Results

Physicochemical characterization of drug loaded nanoparticles

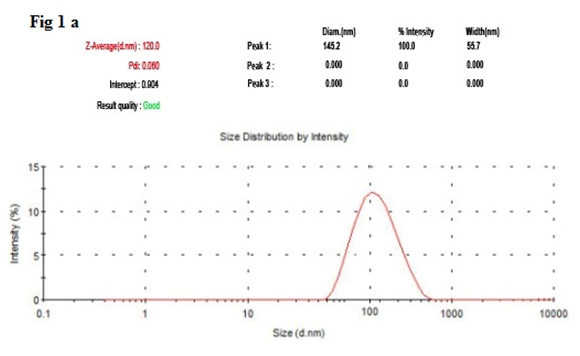

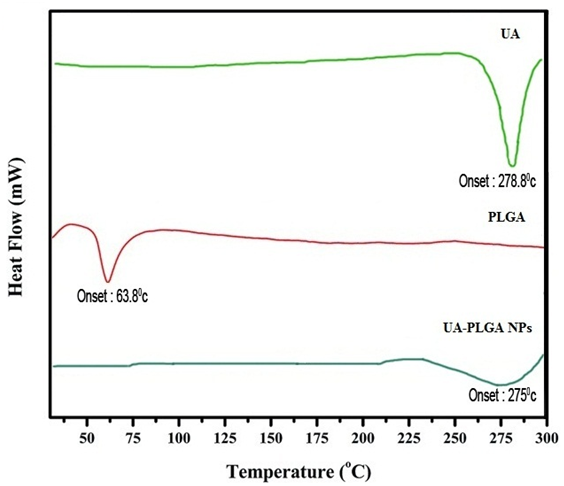

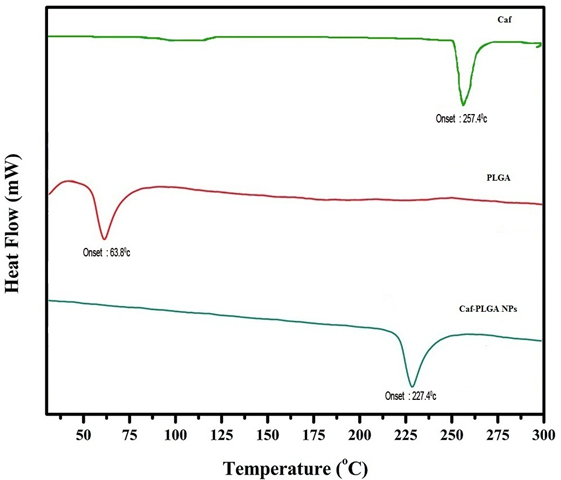

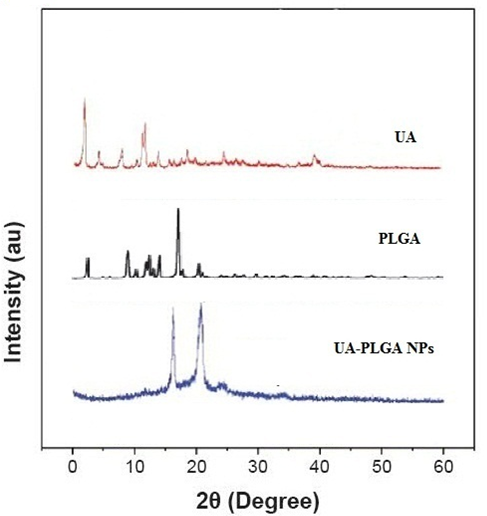

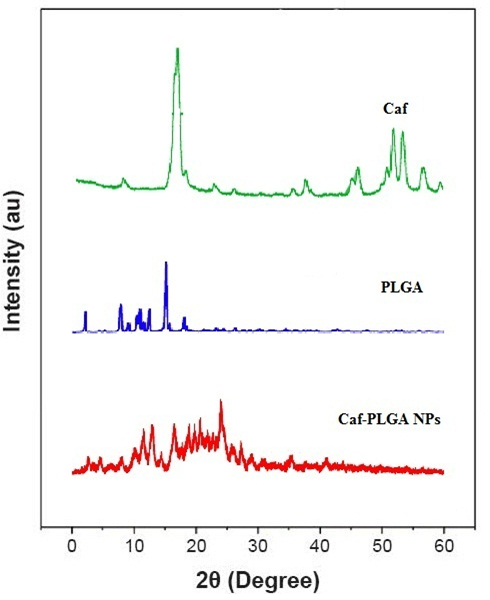

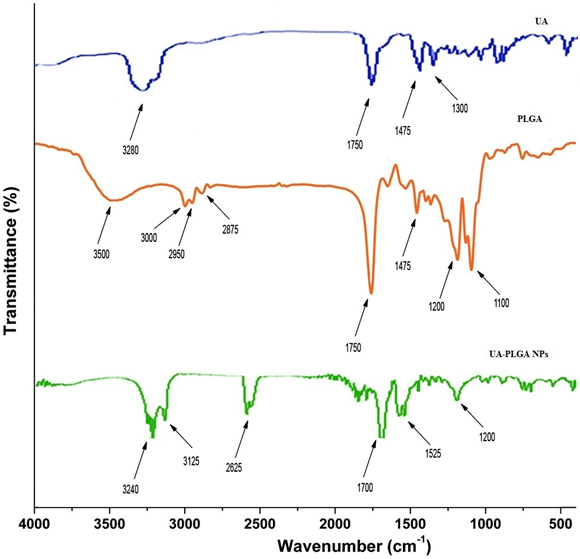

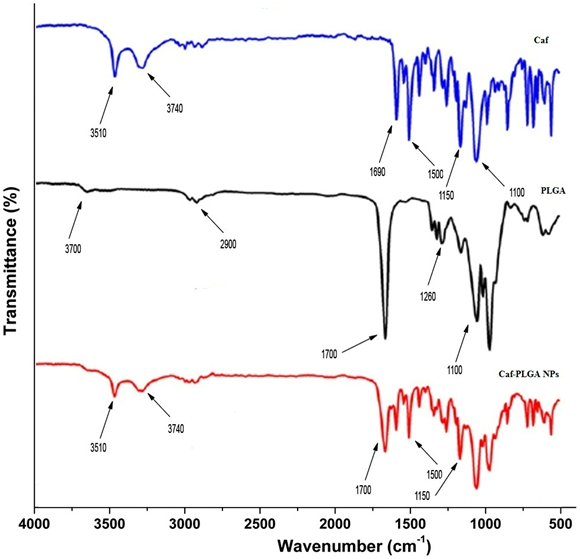

It has been noticed that the prepared UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs possess average size of 120 nm and 100 nm and polydisparsity index (PI) of 0.060 and 0.054 (Figure 1a and b). Further, the prepared UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs had zeta potential of −24.8 mV and −14.3 mV. It has been found that 69 % of UA and 78 % of Caf were encapsulated in PLGA NPs (Table-1). SEM images of the UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs are shown in Figure-2. The prepared UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs had smooth surface but with some irregular small particles. Figure-3 illustrates the TEM image of UA-PLGA nanoparticles and Caf-PLGA nanoparticles which show the nanoparticles were spherical in shape with the size of 120 nm and 100 nm. Further, there was no drug melting peak observed in the DSC curve for UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs are shown in Figure-4 a and b. The broad peak shows that the formulation of UA-PLGA nNPs and Caf-PLGA NPs partially crystalline in nature. The broad peaks observed in the diffractogram at around 20.2° for UA and 25° for Caf in the formulation. The crystallinity decreases during preparation was shown in Figure-5a and b. The FTIR band at 3125 cm-1 is due to stretching vibrations of Ar-H, (-CH) several band at 2625 cm-1 (C-H), 2 or 3 band of methyl group. The presence of aryl carboxylic group in the region 1700 cm-1 represents C=O stretching vibration. Presence of aryl nitro group in the region of 1525 cm-1 is also observed. Etherial group is found at 1200 cm-1, where C-O-C shows very strong stretching in UA-PLGA nanoparticles and the band at 3510 cm-1 represented O-H group stretching of O-H, H-bonded single bridge. The presence of aryl carboxylic group in the region 1700 cm-1 represents C=O stretching vibration. Presence of aryl nitro group in the region of 1500 - 1150 cm-1 is also observed. Etherial group is found at 1150 cm-1, where C-O-C shows very strong stretching for Caf-PLGA nanoparticles shown in Figure-6a and b.

Figure-1 a: Shows the size distribution of UA-PLGA NPs by DLS.

Figure-1 b: Shows the size distribution of Caf-PLGA NPs by DLS.

Table 1: Shows the drug encapsulation efficiency, polydispersity index, size and surface charge of the UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs.

| Fabrications variable | Encapsulation Efficiency (%) |

Mean Diameter (nm) |

Polydispersity index |

Size (nm) | Zeta Potential (mV) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer | Drug | |||||

| PLGA | UA | 69±0.21 | 145.2±80.3 | 0.060±0.11 | 120±4.8 | -24.8±0.4 |

| PLGA | Caf | 78±4.36 | 133.6±39.5 | 0.054±0.09 | 100±4.3 | -14.3±0.5 |

Figure-2: Shows the morphology of UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs by SEM.

Figure-3: Shows the morphology of UA-PLGA nanoparticles and Caf-PLGA nanoparticles by TEM.

Figure-4 a: Show the thermal gravitometric curve of UA-PLGA NPs.

Figure-4 b: Show the thermal gravitometric curve of Caf-PLGA NPs.

Figure-5a: Diffractogram for UA, PLGA and UA-PLGA NPs.

Figure-5b: Diffractogram for Caf, PLGA and Caf-PLGA NPs.

Figure-6a: FTIR spectra of UA, PLGA and UA-PLGA NPs.

Figure-6b: FTIR spectra of Caf, PLGA and Caf-PLGA NPs.

Drug encapsulation efficiency and in vitro drug release:

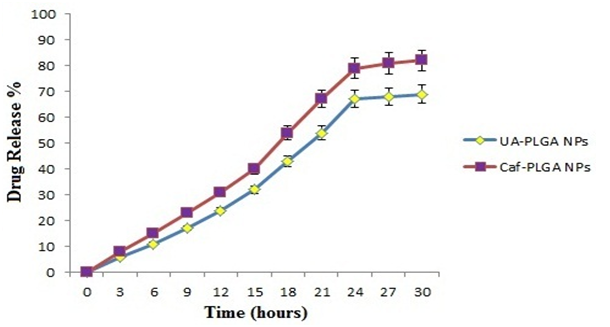

Table-1 shows the amount of drug encapsulated in PLGA nanosystem. The encapsulation efficiencies of UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs are in the range of 69 % and 78 %. Figure-7 shows the % drug release in PBS during different time interval. After 3 h incubation, 7 % of UA and 9 % of Caf was released in the PBS and the maximum of 69 % of UA and 82 % of Caf release were observed upon 30 h incubation. Upon incubation with 10% FBS, 7% and 69% UA was released in 3h and 30 h and 9 % and 82% Caf was released in 3 h and 30 h respectively.

Figure-7: Shows the percentage of UA and Caf released from PLGA nanoparticles during different time intervals in 10% FBS/PBS. Values are given as mean ± S.D. of six experiments in each group.

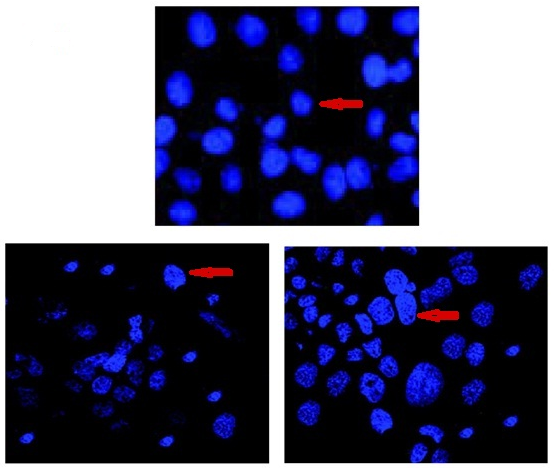

Uptake of drug loaded nanoparticles by HT29 cells:

Visual evidence of UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs uptake by the HT29 cells during 30 min incubation time was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy using Hoechst 33258 dye. UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs treated cells show brighter fluorescence due to enhanced intracellular uptake (Figure-8).

Figure-8: Cellular uptake of UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs by HT29 cells. Microscopic images (Hoechst staining) of HT29 cells incubated with UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs: Enhanced staining indicates improved cellular uptake of UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs.

Drug treatment and dose fixation study:

Figure-9 shows the % cytotoxicity of UA-PLGA NPs, UA, Caf-PLGA NPs and Caf (6.25, 12.5, 25, 50 and 100 μg) in HT29 cells. Inhibitory concentration 50 (IC50) value for UA-PLGA NPs, UA, Caf-PLGA NPs and Caf were found to be 88.10 μg, 79.28μg, 49.63 μg and 43.29 μg respectively.

Figure-9: Optimum dose fixation study by MTT assay. (IC50) value for UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs was found to be 88.10 μg and 69.63 μg, respectively. Values are given as mean ± S.D. of six experiments in each group.

Apoptotic morphological changes:

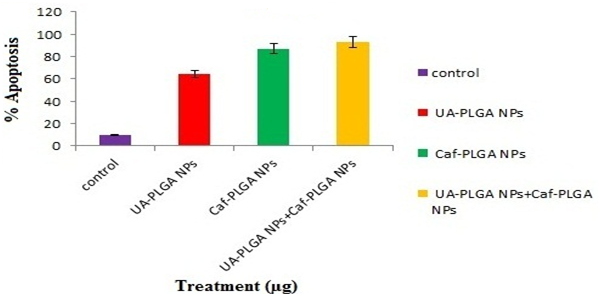

Figure-10A shows the photomicrographs of apoptotic morphological changes in UA-PLGA nanoparticles, Caf-PLGA nanoparticles and UA-PLGA nanoparticles + Caf-PLGA nanoparticles treated cells. The % apoptotic cell death was increased during UA-PLGA nanoparticles, Caf-PLGA nanoparticles and UA-PLGA nanoparticles + Caf-PLGA nanoparticles treatment. It was found that treated cells showed 64%, 87 % and 93% of apoptotic cells, respectively (Figure-10B).

Figure-10a: Orange-red color indicates the occurrence of apoptosis, while green color indicates the absence of apoptosis in HT29 cells.

Figure-10b: Percentage apoptotic cell death was increased in UA-PLGA nanoparticles, Caf-PLGA nanoparticles and UA-PLGA nanoparticles + Caf-PLGA nanoparticles treated cells. Values are given as mean ± S.D. of six experiments in each group.

Discussion

Ursolic acid has various biological properties, including anti-inflammatory, anticancer, anti-angiogenic, and antioxidative activities[5,6]. Caffeine is found in both coffee and tea, so a great number of people are exposed to various doses of caffeine. Caffeine significantly reduces cancer risk caused by environmental and dietary carcinogens[9]. Increase in the specific surface area caused by the formation of smaller nano droplets during the emulsification stage of the process, may facilitate the diffusion of the drug to the external phase along with the solvent, leading to incorporation efficiencies[22,23].

The physicochemical characteristics of colloidal systems, namely size and surface morphology, are recognized to affect their physical stability and to significantly influence their interaction with the release rate of an incorporated drug and their interaction with cells[24,25]. The method used in this work allowed the instantaneous and reproducible formation of UA-PLGA NPs exhibiting diameters below 120 nm and low polydispersity indexes, indicating a homogeneous size distribution. The mean zeta potential of UA-PLGA NPs exhibited a negative value of 24.8 ± 0.4 mV and Caf-PLGA NPs exhibiting diameters below 100 nm and low polydispersity indexes, indicating a homogeneous size distribution. The mean zeta potential of Caf-PLGA NPs exhibited a negative value of 14.3 ± 0.5 mV. The melting endothermic peak of pure UA appeared at 278.8°C and the peak of Caf appeared at 257.4°C. However no melting was detected for both nanoparticle formulations. Thus, it can be concluded that UA in the nanoparticle and Caf in the nanoparticle were in an amorphous or disordered crystalline or in the solid solution state. The method used in this work allowed the instantaneous and reproducible formation of nanoparticles exhibiting diameter below 120 nm and low polydispersity indexes, indicating a homogeneous size distribution. As mentioned above, these findings were confirmed by the TEM data which also showed that nanospheres were spherical in shape. Nanoparticles were shown to exhibit a negative surface charge which can be attributed to the type of polymer used and more specifically to the presence of polymeric carboxylic groups on the nanoparticle surface[26,27].

Further, we noticed that the PLGA degraded gradually and released the drug in a sustained manner. 7% UA was released in 3h and 69% UA was released in 30 h incubation in the PBS and 9% Caf was released in 3h and 82% Caf was released in 30 h incubation in the PBS. This result indicates that the prepared nanoparticles are useful for controlled delivery system for cancer treatment[28]. UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs/Hoechst 33258 entered the cells during the incubation period and the fluorescence was found inside the nuclei, which indicate that UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs might prove to be useful in site specific delivery of drugs whose site of pharmacological activity might be the cell nucleus, which has been evidenced by diminished fluorescence observed in Figure-5.

Furthermore, we evaluated the anticancer activity of UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs in HT29 cell line. It was found that UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs could greatly inhibit the HT29 cell growth. The reason for increased cytotoxicity observed in the UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs group might be due to increased cellular uptake and sustained drug delivery. Enhanced cytotoxicity during UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs treatment indicates that PLGA has the potency to transport more UA and Caf into the cells, thus achieving greater cytotoxicity. IC50 values for UA-PLGA NPs and Caf-PLGA NPs in our study were 88.10 μg and 49.63 μg. Previously 88.69 μM value reported before for PTX[29]. We have observed UA-PLGA nanoparticles + Caf-PLGA nanoparticles pretreatment significantly increased apoptotic morphological changes in HT29 cells than UA-PLGA nanoparticles and Caf-PLGA nanoparticles treatment alone. Apoptosis has been shown to be a significant mode of cell death after cytotoxic drug treatment[30]. Further studies warrants to explore the merits of UA-PLGA NPs + Caf-PLGA NPs for cancer chemotherapy.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

References

[1] Siegel, R., Ma, J., Zou, Z., et al. Cancer statistics. (2014) CA Cancer J Clin 64(1): 9-29.

[2] Tseng, C.L., Su, W.Y., Yen, K.C., et al. The use of biotinylated-EGF- modified gelatin nanoparticle carrier to enhance cisplatin accumulation in cancerous lungs via inhalation. (2009) Biomaterials 30(20): 3476–3485.

[3] D’Angelillo, R.M., Trodella, L., Ciresa, M., et al. Multimodality treatment of stage III non-small cell lung cancer: analysis of a phase II trial using preoperative cisplatin and gemcitabine with concurrent radiotherapy. (2009) J Thorac Onco 4(12): 1517-1523.

[4] Shabbits, J.A., Hu, Y., Mayer, L. D. Tumor chemo sensitization strategies based on apoptosis manipulations. (2003) Mol Cancer Ther 2(8): 805–813.

[5] Zheng, Q.Y., Jin, F.S., Yao, C., et al. Ursolic acid-induced AMP activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation contributes to growth inhibition and apoptosis in human bladder cancer T24 cells. (2012) Biochem Biophys Res Commun 419(4): 741-747.

[6] Limami, Y., Pinon, A., Leger, D.Y., et al. HT- 29 colorectal cancer cells undergoing apoptosis overexpress COX-2 to delay ursolic acid-induced cell death. (2011) Biochimie 93(4): 749-757.

[7] Novotny, L., Vachalkova, A., Biggs, D. Ursolic acid: an anti-tumorigenic and chemopreventive activity minireview. (2001) Neoplasma 48(4): 241–246.

[8] Neto, C.C. Cranberry and its phytochemicals: a review of in vitro anticancer studies. (2007) J Nutr 137: 186-193.

[9] Kesavan, P.C. Oxygen effect in radiation biology: Caffeine and serendipity. (2005) Current Science 89(2): 318-328.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others

[10] Abraham, S.K. Inhibitory effects of coffee on the genotoxicity of carcinogens in mice. (1991) Mutation Research 262(2): 109-114.

[11] Fries, N., Kihlman, B. Fungal mutations obtained with methyl xanthines. (1948) Nature 162: 573-574

[12] Caddeo, C., Teska, K., Sinico, C., et al. Effect of resveratrol incorporated in liposomes on proliferation and UV-B protection of cells. (2008) Int J Pharm 363(1-2): 183–191.

[13] Leroux, J.C., Doelker, E., Gurny, R. The use o obtained f drug-loaded nanoparticles in cancer chemotherapy. (1996) Micro encapsulation 535-575.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others

[14] Matsumura, Y., Maeda, H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. (1986) Cancer Res 46(12): 6387–6392.

[15] Hashida, M., Akamatsu, K., Nishikawa, M., et al. Design of polymeric pro drugs of prostaglandin E1 having galactose residue for hepatocyte targeting. (1999) J Control Release 62(1-2): 253–262.

[16] Nori, A., Kopecek, J. Intracellular targeting of polymer-bound drugs for cancer chemotherapy. (2005) Adv Drug Deliv Rev 57(4): 609–636.

[17] Peterson, C.M., Shiah, J.G., Sun, Y., et al. HPMA copolymer delivery of chemotherapy and photodynamic therapy in ovarian cancer. (2003) Adv Exp Med Biol 519: 101–123.

[18] Torchilin, V.P., Lukyanov, A.N. Peptide and protein drug delivery to and into tumors: challenges and solutions. (2003) Drug Discov Today 8(6): 259–266.

[19] Gao, X., Cui, Y., Levenson, R.M. In vivo cancer targeting and imaging with semiconductor quantum dots. (2004) Nat. Biotechnol 22: 969–976.

[20] Cho, K., Wang, X., Nie, S., et al. Therapeutic nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer. (2008) Clinical Cancer Research 14: 1310–1316.

[21] Gomez-Gaete, C., Tsapis, N., Besnard, M., et al. Encapsulation of dexamethasone into biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles. (2007) Int J Pharm 331(2): 153–159.

[22] Bodmeier, R., Maincent, P. Polymeric dispersions as drug carriers, in: H.A. Lieberman, M.M. Rieger, G.S. Banker (Eds.). (1998) Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms: Disperse Systems 3: 87–127.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others

[23] Govender, T., Stolnik, S., Garnett, M.C., et al. PLGA nanoparticles prepared by nanoprecipitation: drug loading and release studies of a water soluble drug. (1999) J Control Release 57(2):171–185.

[24] Pavillard, V., Nicolaou, A., Double, J.A., et al. Methionine dependence of tumours: a biochemical strategy for optimizing paclitaxel chemosensitivity in vitro. (2006) Biochem Pharmacol 71(6): 772-778.

[25] Halliwell, B., Gutteridge, J.M.C. Free radicals in biology and medicine. (1986) Oxford: Clarendon Press 75(1): 105-106

[26] Mauduit. J., Vert, M. Less polymers based poly (lactic acid glycolic acid) delivery control drug principle effect. (1993) STP Pharma Sci 3(3): 197-212.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others

[27] Lacasse, F.X., Filion, M.C., Phillips, N.C., et al. Influence of surface properties at biodegradable microspheres surfaces: effects on plasma protein adsorption and phagocytosis. (1998) Pharm Res 15(2): 312-317.

[28] Hildeman, D.A., Mitchell, T., Teague, T.K., et al. Reactive oxygen species regulate activation-induced T cell apoptosis. (1999) Immunity 10(6): 735-744.

[29] Zhang, M., Boyer, M., Rivory, L., et al. Radiosensitization of vinorelbine and gemcitabine in NCI-H460 non–small-cell lung cancer cells. (2004) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 58(2): 353–360.

[30] Lakshmi, S., Dhanaya, G.S., Joy, B., et al. Inhibitory effect of an extract of Curcuma Zedoariae on human cervical carcinoma cells. (2008) Med Chem Res 17(2-7): 335-344.

[31] Peltonen, L., Koistinen, P., Hirvonen, J. Preparation of nanoparticles by the nanoprecipitation of low molecular weight poly (l) lactide. (2003) STP Pharma Sci 13: 299-304.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others

[32] Mathew, M.E., Mohan, J.C., Manzoor, K., et al. Folate conjugated carboxymethyl chitosan-manganese doped zinc sulphide Nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery and imaging of cancer cells. (2010) Carbohydrate polymers 80(2): 443-449.

[33] Dong, Y., Feng, S.S. Methoxypoly (ethylene glycol)-poly (lactide) (MPEG-PLA) nanoparticles for controlled delivery of anticancer drugs. (2004) Biomaterials 25(14): 2843-2849.

[34] Karthikeyan, S., Prasad, N.R., Gnanamani, A., et al. Anticancer activity of resveratrol-loaded gelatin nanoparticles on NCI-H460 non-small cell lung cancer cells. (2013) Biomedicine and preventive nutrition 3(1): 64-73.

[35] Mosmann, T. Rapid calorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application of proliferation and cytotoxicity assay. (1983) J Immol Methods 65(1-2): 55-63.

[36] Zhou, H.B., Yan, Y., Sun, Y.N., et al. Resveratrol induces apoptosis in human esophageal carcinoma cells. (2003) World J Gastroenterol 9(3): 408–411.