The Beneficial Reuse of Power Plant Heated Effluent and Intense Light Arrays to Control Harmful Algal Blooms

Kevin C. Owen1*, J. Craig Swanson2, Bryan Weinstein1, Deborah Crowley3, Daniel P. Owen4 and Jenna L. Owen Venero1

Affiliation

- 1Les Mers, LLC, 15469 Osprey Glen Drive, Lithia, FL 33547, USA

- 2Swanson Environmental Associates LLC, 78 Sycamore Lane, Sauderstown, RI 02874, USA

- 3RPS, 55 Village Square Drive, South Kingstown, RI, 02879, USA

- 4University of Georgia, Department of Marine Sciences, 102 Marine Science Building, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602

Corresponding Author

Kevin C. Owen, Les Mers, LLC, 15469 Osprey Glen Drive, Lithia, FL 33547, USA, Tel: (813) 924-4785; E-mail: kowen1972@yahoo.com

Citation

Owen, K.C., et al. The Beneficial Reuse of Power Plant Heated Effluent and Intense Light Arrays to Control Harmful Algal Blooms. (2017) J Marine Biol Aquacult 3(1): 1- 6.

Copy rights

© 2017 Owen, K.C. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Harmful algal Blooms; Beneficial reuse of wastewater; Light arrays; Red tides

Abstract

A number of control technologies have been proposed to respond to, and help control, harmful algal blooms (HABs) including mechanical, biological, chemical, genetic, and/or environmental treatment concepts. HAB control technologies should focus on accelerating or amplifying natural processes or conditions that act to terminate HABs without the introduction of foreign materials that could remain in the environment as residues. Two potential technologies, the beneficial reuse of heated wastewater from power plants and arrays of intense lights are discussed in this paper First; a CORMIX model simulation on the impacts of a thermal plume discharge is presented. The model results show that the discharge of a large volume of heated wastewater, as from a thermal power plant, could affect a significant, but controllable volume of water impacted by a HAB. Second, the results of a field test of a prototype of a high-intensity light array (the Owen-Weinstein Light Array) are also presented. This light array was tested during a Karenia brevis HAB event in the Intracoastal Waterway in Sarasota, Florida in November 2015. Secchi disk depth was used as a field indicator for changes in the density of the Karenia brevis bloom at the test, background, and control locations. The Secchi disk depth was found to be greater and significantly different than the Secchi disk depth at both the control and background locations. Further, there was no significant difference in the Secchi disk depths at the control and background locations.

Introduction

A number of concepts have been investigated for controlling or reducing the severity of harmful algal blooms (HABs), commonly referred to as red tides. Many of these concepts, some of which have been tested, involve the introduction of chemical or physical materials, organisms, and biological agents into areas subject to a HAB. Such concepts could result in the accumulation of the introduced materials into the environment that may persist after the HAB has subsided[1]. These concepts involving the introduction of foreign materials are also limited by the volume of water that can be applied, because of the need to procure and transport large volumes to the location of a HAB. Therefore, a HAB could redevelop or be re-introduced to an area creating the need for subsequent or on-going treatments and associated logistical complications[2].

HAB control technologies should focus on accelerating or amplifying natural processes or conditions that act to terminate HABs without the introduction of foreign materials that could remain in the environmental as residues. Concepts have been proposed to disrupt environmental conditions such as water temperature, salinity, light intensity, dissolved oxygen, and stratification that might otherwise support and propagate HABs[3-9].

This paper investigates the feasibility of two concepts proposed to help control HABS through the manipulation of two environmental factors: water temperature and light intensity[6-9]. To manipulate temperature, the beneficial reuse of heated wastewater from thermal power plants could be discharged to locally raise the water temperature to levels that are lethal to HAB organisms. In the case of Karenia brevis (K. brevis), the dinoflagellate that causes HABs in Florida, the lethal temperature has been experimentally determined to be 30°C[10].

A preliminary analysis was conducted to explore the potential viability of using the heated effluent from power plants using once-through cooling. The working concept is that a vessel containing a volume of heated water would discharge its contents into waters in which a HAB is occurring at a temperature sufficient to kill the organism. The analysis is to provide a first order estimate of the volume of water that would be subject to a temperature equal to 30°C or greater. There were two approaches used to estimate the resulting volume: a mass dilution calculation and a near field plume model calculation.

The introduction of high intensity light has been postulated as another method of manipulating environmental conditions to limit the growth, persistence, and propagation of HABs. A light array was constructed and tested in a K. brevis bloom in the Intracoastal Waterway on the west coast of Florida in 2015. The results of the thermal plume analysis and the field test of the high intensity light array are discussed in this paper.

Neither the beneficial reuse of heated wastewater from thermal power plants nor the use of intense light arrays would result in the accumulation of potentially deleterious materials in the environment. The prevalence of heated wastewater and the ease of using lights offer the potential for repetitive treatments in areas if a HAB were to redevelop or be re-introduced.

Materials and Methods

Thermal volume dilution

For the purposes of assessing the effect of a discharge of heated wastewater on ambient conditions, arbitrary values of the controlling parameters were chosen and summarized in Table 1: Input for Thermal Plume Analysis.

Table 1: Input for Thermal Plume Analysis.

| Parameter | Units | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Available Discharge Volume | Gal | 1 x 106 | Tank volume on vessel |

| Discharge Temperature | °C | 37 | From thermal discharge of power plant |

| Ambient Water Temperature | °C | 27 | Typical level in waters offshore Florida |

| Discharge Water Density | Kg/m³ | 1022.8 | From thermal discharge of power plant |

| Ambient Water Density | Kg/m³ | 1019.2 | Typical level in waters offshore Florida |

| Mortality Threshold for organism | °C | 30 | |

| Depth of discharge | m | 7 | For use in CORMIX model |

| Orientation of discharge | NA | NA | Horizontal, parallel to the ocean current direction |

A study of once-through power plant cooling systems in the United States found that, on the average, the temperature of the discharge water averaged between 9.5°C and 10°C higher than the ambient intake water during the summer months. Therefore, in these thermal evaluations, a difference of 10°C between the discharge water and ambient temperature was assumed.

A discharge with elevated temperature (above the ambient temperature) will entrain surrounding ambient waters which results in a discharge plume of both waters (discharge and entrained ambient) at temperatures between ambient and discharge temperature. So long as the ambient currents allow for passive transport of the discharge plume, new waters will continue to be entrained in to the plume.

The potential for ‘treating’ a volume of ambient waters in areas experiencing a HAB such that they reach or exceed the mortality threshold is a function of the discharge volume, the discharge temperature, and the ambient temperature. A first order calculation of the volume of ambient water that could be mixed with the discharge and induce mortality can be made based on the volume available, discharge temperature, and ambient temperature. The total volume of ambient water that could be mixed with the discharge to reach temperatures at or above the mortality can be calculated based on the following general principles of conservation of water mass and energy (thermal) in the combined plume (discharge plus entrained volumes). The total water mass of the plume can be defined as:

Vplume = Vdis + Vamb

The total thermal energy can be defined as:

Tplume x Vplume = Tdis x Vdis + Tamb x Vamb

Defining that the average temperature of the plume, Tplume, is equal to Tmort, the water temperature lethal to K. brevis (30°C), then the above two equations can be combined to define the volume of ambient water,

Vamb, to be Vamb = (Tdis – Tmort) / (Tmort – Tamb) x (Vdis)

In these equations:

Vamb is the volume of ambient water entrained into the plume

Vdis is the volume of heated water discharged at the treatment location (1 x 106 gallons [gal])

Vplume is the volume of the plume with average temperature Tplume

Tamb is the ambient water temperature at the treatment location (27°C)

Tdis is the temperature of the discharge water (37°C)

Tplume is the average temperature of the plume

Tmort is the water temperature that is lethal to K. brevis (30°C)

Through the use of these equations, the volume of the receiving water that would be heated to the average temperature that is lethal to K. brevis (i.e., 30°C) can be calculated. It should be noted that the plume is defined by the average temperature, Tmort, where some water would be greater than Tmort and some would be less than Tmort in this first order calculation.

CORMIX model application

The CORMIXmodel is a rule-based near field plume model supported by the United States Environmental Protection Agency and used extensively in the United States and elsewhere. The model predicts the dimensions and dilution of a submerged plume from its discharge point downstream to the point where its initial momentum has dissipated, which is known as the end of the near field region. The discharge is assumed located at a depth of 7 meters (m) below the surface and is oriented horizontally in the downstream direction of ambient flow. For idealized treatment, the wind driven surface heat exchange was assumed zero. A series of 19 model runs were made with different discharge port dimensions and ambient currents to determine the largest plume size as defined by plume centerline downstream distance and depth. The plume cross section area was also calculated. The excess temperature is defined as the temperature rise above ambient and calculated from its value of 10°C above the ambient at the discharge location to its value of 3°C above ambient at the mortality threshold.

Intense Light Array

A prototype of a high-intensity light array (the Owen-Weinstein Light Array) was constructed consisting of three 500-Watt halogen lights. The lights were mounted on a steel frame in a triangular shape. This light array was tested during a K. brevis HAB event in the Intracoastal Waterway at 3567 Bayou Louise Lane, Sarasota, Florida in November 5, 2015. The array was suspended by a dock with electricity supplied at the dock. The array was suspended so that the top two lights were at a depth of 0.8 m below the water surface and the third light at a depth of 1.2 m.

Secchi disk depth was used as a field indicator for changes in the density of the K. brevis bloom at the test, background, and control locations. Water temperatures were measured by a YSI meter at the test, background, and control locations. The background data was obtained by measuring Secchi disk depth and temperature at the test location for one-half hour immediately before the test was started. The control data was obtained at a location on the dock ten yards away from the test location, perpendicular to the light direction and outside the influence of the lights. The test was conducted at slack tide and lasted for 2.5 hours.

Results

Volume Dilution Results

As stated in the Methods section, the total volume of ambient water that could be mixed with the discharge to reach an average temperature at mortality can be calculated based on the following equation:

Vamb = (Tdis – Tmort) / (Tmort – Tamb) x (Vdis)

Which for this example would be:

Vamb = (37°C - 30°C) / (30°C - 27°C) x (1 x 106 gal) = 2.33 x 106 gal

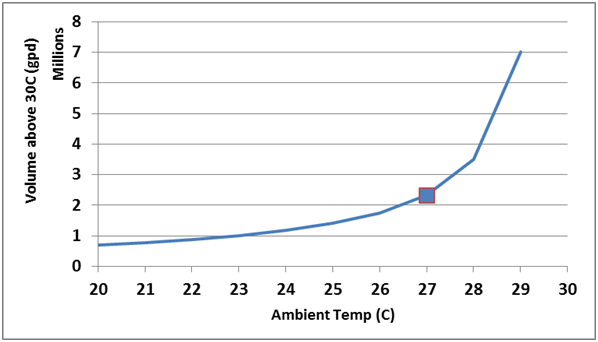

The relationship of potential ‘treated’ ambient water volume to ambient temperature based on a discharge volume of 1 X 106 gal and discharge temperature of 37°C is shown in Figure 1. The marker shows the results for the ambient temperature of 27°C.

Figure 1: Average volume of water (million gallons per day (million gpd)) heated to the lethal temperature of K. brevis (30°C or higher) versus the ambient water temperature by a discharge of 1 million gallons per day (1 x 106 gal) at a temperature of 10°C above ambient.

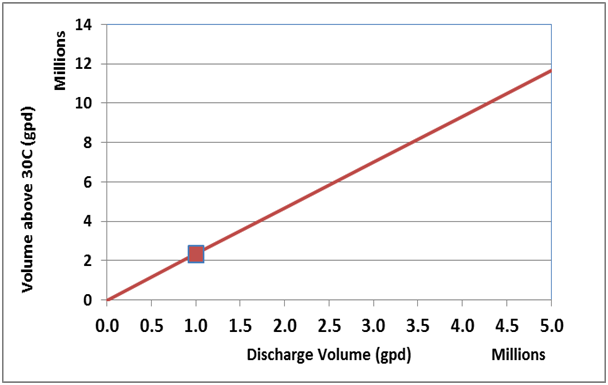

The variation of average volume above 30°C as a function of discharge volume is shown in Figure 2. The relationship is linear where the ambient volume is 2.33 times the discharge volume.

Figure 2: Average volume of water (million gpd) heated to the lethal temperature of K. brevis (30°C or higher) versus the ambient water temperature by different discharges (million gpd) at a temperature of 10°C above ambient.

CORMIX model results

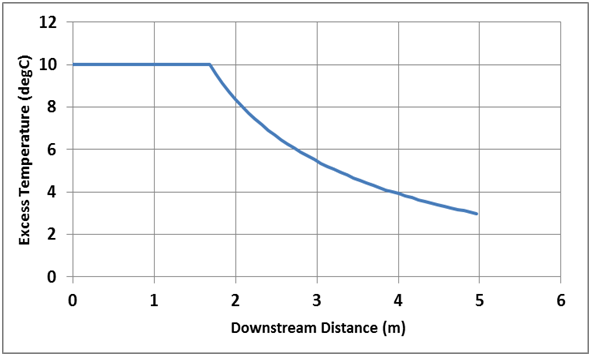

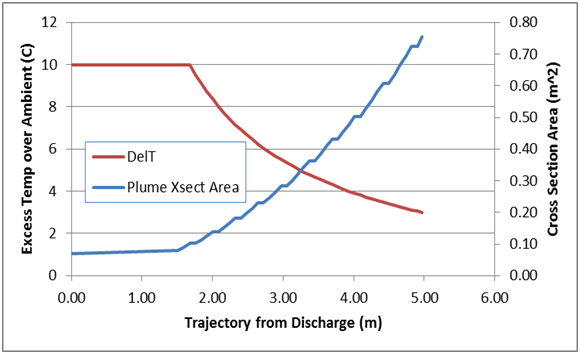

Figure 3 shows the excess temperature as a function of centerline downstream distance. The plume extends 5 m before the 3°C mortality threshold is reached; smaller plume dimensions were noted for conditions which had increased exit velocity or momentum.

Figure 3: CORMIX model results showing variation of excess temperature above ambient along plume centerline versus distance downstream from the discharge.

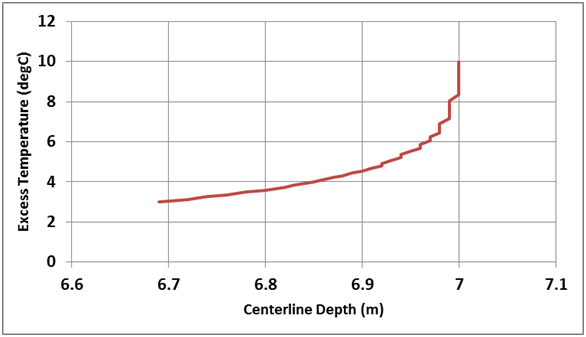

Figure 4 shows the excess temperature as a function of centerline depth below the surface starting at the initial discharge depth of 7 m. Due to the small positive buoyancy from the relatively small difference between discharge and ambient densities, the plume centerline rises only 0.3 m before the 3°C mortality threshold is reached.

Figure 4: CORMIX model results showing variation of excess temperature above ambient along plume centerline versus depth of the centerline of the plume.

Figure 5 shows the excess temperature and the plume cross sectional area as a function of the plume trajectory. The plume centerline trajectory is defined as the combination of plume distance downstream and plume buoyancy upward. Since the downstream movement (5 m) is much larger than the upward movement (0.3 m) the shape of the excess temperature curve (DelT) is indistinguishable to the one in Figure 4 which shows excess temperature vs the downstream direction dimension. The plume cross sectional area starts at the discharge at 0.07 m² and increases to 0.75 m² when the plume centerline excess temperature drops to 3°C.

Figure 5: CORMIX model results showing excess temperature above ambient along plume centerline versus trajectory of plume centerline away from discharge.

The discharge plume characteristics would remain constant assuming the discharge conditions remain constant. While the CORMIX results show a small plume above the threshold mortality, it would be a constantly formed plume that entrains new ambient waters assuming the circulation is such that it transports the plume waters away from the source unidirectional or at least in a manner where the discharge plume is not re-circulated/ re-entrained.

Intense light array results

The results of the light array test are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Light Array Test Results.

| Time (minutes) | Test Location | Control Location | Test vs. Background | Test vs. Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp. (°C) | Secchi Disk Depth (ft) | Temp. (°C) | Secchi Disk Depth (ft) | |||

| 0 | NS | 4.0 | Background at Test Location | |||

| 28 | 28.4 | 4.0 | Background at Test Location | |||

| 36 | NS | 4.0 | Background at Test Location | |||

| 45 (Start) | 28.2 | 4.5 | 28.4 | 4.5 | + 0.5 | 0 |

| 60 | 28.1 | 4.5 | 28.3 | 4.0 | + 0.5 | + 0.5 |

| 75 | 28.0 | 4.5 | 28.1 | 4.5 | + 0.5 | 0 |

| 90 | 28.1 | 5.0 | 28.3 | 4.5 | + 1.0 | + 0.5 |

| 105 | 28.2 | 4.5 | 28.3 | 4.0 | + 0.5 | + 0.5 |

| 120 | 28.2 | 4.5 | 28.4 | 4.0 | + 0.5 | + 0.5 |

| 135 | 28.2 | 5.0 | 28.3 | 4.0 | + 1.0 | + 1.0 |

The temperature and Secchi disk depth data for the test location, background and control location were subjected to a Students’ T-test. At the 95% confidence level, the Secchi disk depth at the test location was found to be greater and significantly different than the Secchi disk depth at both the control and background locations. Further, there was no significant difference in the Secchi disk depths at the control and background locations. There were no significant differences in water temperature at any of the three locations.

Discussion

A number of control technologies have been proposed to respond to, and help control, harmful algal blooms (HABs) including mechanical, biological, chemical, genetic, and/or environmental treatment concepts[2]. HAB control technologies should focus on accelerating or amplifying natural processes or conditions that act to terminate HABs. Environmental conditions that could be manipulated to control HABs include water temperature, salinity, light intensity, dissolved oxygen, and stratification. The manipulation of temperature or salinity by the beneficial reuse of heated wastewater from power plants or of hypersaline wastewater from desalination plants could be effective in responding to large scale HABs in open water. On a much smaller scale, arrays of intense lights could be used to protect water intakes or other locally exposed resources[6-9].

Control technologies that focus on the manipulation of environmental conditions to control HABs, such as the two evaluated in this paper, offer a number of benefits. First, no foreign materials, chemicals, organisms or biological agents that could create long-term, adverse environmental impacts are introduced. As demonstrated in the thermal analysis, the thermal effects from the beneficial reuse of thermal plant wastewater are quite limited and rapidly approach ambient or non-lethal levels. The intense light arrays do not appear to have significant thermal impacts and only limited impacts of elevated lights that are dependent of the water absorption and transmissivity.

These technologies offer a feasible method of responding to HABs that repetitively redevelop or are re-introduced into an area. Technologies that involve the dispersal of foreign materials, chemicals, or biological controls would need these materials to be re-supplied to an area, which could be logistically or economically difficult. Heated wastewater is a continuous product from thermal power plants and electricity to the intense light arrays can be continuously supplied from either direct current (DC) or alternating (AC) sources.

These technologies also offer the potential to scale the magnitude of the control response to accommodate the location, environment, and sensitive resources in the area of a HAB. The spatial area impacted by the discharge of heated wastewater can be controlled through the geometry, depth, and rate of the discharge, based upon a consideration of the receiving water temperature and currents and wind conditions. The impact of the light array can be controlled by the number, intensity, and spacing of the lights within the arrays. Additional modeling and testing, including more field testing in HABs, are needed to be able to scale the treatment to successfully control or limit HABs.

Conclusion

In terms of response, control, and treatment, HABs can be considered to be similar to other large-scale, complex environmental incidents such as spills or releases of oil, chemical, or other hazardous liquids. Often the scope and complexity of those incidents require the use of a large variety or control and treatment technologies over what could be a large spatial area and period of time. For example, responses to major oil spills could involve technologies including booms and other physical barriers, skimmers and other methods of manual removal and cleaning including sorbents and vacuums, flushing, the use of dispersants or emulsion agents, the use of microbiological agents and the removal of contaminated sediment, debris, and vegetation, among other techniques.

In a similar manner, the successful control or treatment of HABs may necessitate the application of multiple approaches and technologies, depending on the location, environment, and sensitive resources. The beneficial reuse of heated water from thermal plants and the use of intense light arrays are two possible technologies. Additional testing and development of these technologies are needed to design field scale parameters for controlling HABs. However, our initial research indicates that these technologies offer promising, low cost, low environmental impact, and easily implemental ways to significantly decrease the detrimental effects of HABs in both marine and freshwater environments.

Acknowledge:

The construction of the prototype light array was funded in part by Solutions to Avoid Red Tides (START). The authors would like to acknowledge the support of START and its director, Sandy Gilbert. The prototype light array was tested at the Sarasota Bay Watch property and the assistance of that organization and its director, Larry Stultz, is appreciated. The authors would also like to thank Fred Crabill and his company, Southeast Environmental Solutions, Inc. (SESI) for providing the field meters for the test of the prototype light array.

Disclaimer:

The ideas, opinions, and views presented in this paper are solely those of the authors and Les Mers, LLC, and may not necessarily be those of the other companies or organizations the authors may be associated or affiliated with.

References

- 1. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) (2014) Draft Programmatic Environmental Assessment for the Prevention, Control, and Mitigation of Harmful Algal Blooms Program pp: 1-75.

- 2. Owen, KC, Owen JL, Owen DP (2013) “A Potential Mechanism for the Regrowth of Harmful Algal Blooms following Clay Treatment.” Intern. J. of Integrative Biol 14: 10 – 16.

- 3a. Corliss JO, Esser SC (1974) Comments on the role of the cyst in the life cycle and survival of free-living protozoans. Trans Amer Micros Soc 93: 578 – 593.

- 3b. Sarjeant W (1974) Fossil and living dinoflagellates. Acad. Press, NY.

- 3c. Owen KC, Norris DR (1984) Cysts of the thecate dinoflagellate Fragilidium, Balech ex Loeblich. Litoralia 1:59 – 64.

- 3. Owen KC, Owen JL, Owen DP (2013) “Floating Desalination and Water Pumping Plants as Harmful Algal Bloom Control Technologies.” J Marine Sci Res Dev 7: 1-4.

- 4. Owen KC, Owen JL, Owen DP (2013) “Proposed Harmful Algal Bloom Control Technologies: Floating Desalination and Water Pumping Plants.” 7th Symp.on Harmful Algae in the U.S.

- 5. Owen KC, Owen JL, Owen DP (2013) “The Use of a Floating Desalination Plant to Treat Harmful Algal Blooms.” Intern. Conf. on Oceanography (124th OMICS Group Conference). Abstract in J Marine Sci. Res Dev 3: 38.

- 6. Owen, KC (2016) “The Beneficial Reuse of Hypersaline Waste Water from Desalination Plants to Treat Harmful Algal Blooms.” Fisheries and Aquaculture J 3: e125. doi:10.4172/2150-3508.1000e125

- 7. Magana HA, Villareal TA (2006)“The effect of environmental factors on the growth rate of Karenia brevis (Davis) G. Hansen and Moestrup.” Harmful Algae 5: 192-198.

- 7a. Madden N, Lewis A, Davis M (2013) “Thermal effluent from the power sector: an analysis of once-through cooling system impacts on surface termperature.” Env, Res. Letters 8: 8pp (doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/3/035006).

- 8. Jirka GH; Doneker RL, Hinton SW(1996)“User'smanualfor CORMIX. A hydrodynamic mixing zone model and decision support system for pollutant discharges into surface waters.” U.S.Environmental Protection Agency. 152pp.

- 9. NOAA (2013) “Characteristics of Response Strategies: A Guide for Spill Response Planning in Marine Environments.” 76 pp.

- 10. Corn ML, Copeland C (2010) “The Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill: Coastal Wetland and Wildlife Impacts and Response.” Congressional Research Service 7-5700, R41311: 29 pp.