Therapeutic Targeting of Tumorigenesis and Tumor Disease -For Clinical Analysis of Epigenetics and Epigenome

Affiliation

Department of Pediatrics, Section of Hematology/Oncology, Augusta, USA

Corresponding Author

Biaoru Li, Department of Pediatrics, Section of Hematology/Oncology, Georgia Cancer Center, MCG, Augusta, GA, USA 30912, E-mail: BLI@gru.edu

Citation

Li, B., et al. Therapeutic Targeting of Tumorigenesis and Tumor Disease - For Clinical Analysis of Epigenetics and Epigenome. (2017) Int J Hematol Ther 3(1): 1- 12.

Copy rights

© 2017 Li, B. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Tumorigenesis; Epigenetics

Introduction

Tumorigenesis, in general, is originated from two types of gene alterations, a tumor suppressor gene and a proto-oncogene/ oncogene. A tumor suppressor gene, or anti-oncogene, is a gene that protects a cell from tumorigenesis. When this gene mutates, it causes a loss or reduction in its protection[1]. A proto- oncogene is a normal gene coding proteins which regulate cell growth and differentiation in normal circumstance. Once the proto-oncogene has an activating mutation, it will cause aberrance of cell differentiation, finally resulting in tumorigenesis. Additionally, higher expression and chromosomal translocations of proto-oncogenes also could lead to tumorigenesis[2].

Although these DNA sequences of tumor suppressor gene and oncogene with their aberrant changes are extensively studied in tumor disease, some genetic changes are not involved in encoded DNA sequence rather than a gene switch on and off from external or environmental factors. Scientists concluded the aberrant changes as epigenetics (prefix epi- Greek means over, outside of, around). The term ‘epigenetics’ regarding aberrant changes of tumor suppressor gene and oncogene emerged in the 1990s. The concept of epigenetics was described as “stably heritable phenotype resulting from changes in a chromosome without alterations in the DNA sequence” at a Cold Spring Harbor meeting in 2008. Currently, epigenetics is focusing on DNA methylation and histone modification for clinical analysis of therapeutic targeting of tumor prevention and treatment[3].

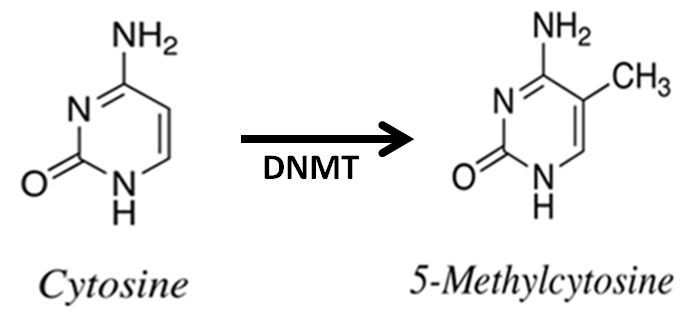

As Figure-1, in mammalian cells, DNA methylation occurs mainly at the C5 position of CpG dinucleotides and is carried out by two general classes of enzymatic activities - maintenance methylation and de novo methylation. Maintenance methylation is necessary to preserve DNA methylation after every cellular DNA replication cycle. Without the DNA methyltransferase (DNMT), the replication function itself would produce unmethylated daughter strands called as passive demethylation. There are several types of DNMTs, DNMT1 is a maintenance methyltransferase that is responsible for copying DNA methylation patterns to the methylated daughter strands during DNA replication. DNMT2 is homolog of DNMT1, containing all 10 sequence motifs common to all DNA methyltransferases; however, DNMT2 (TRDMT1) does not methylate DNA but instead methylates cytosine-38 in the anticodon loop of aspartic acid transfer RNA. DNMT3a and DNMT3b are the de novo methyltransferases that set up DNA methylation patterns early in development. DNMT3L is a protein that is homologous to the other DNMT3s but has no catalytic activity so that DNMT3L assists the de novo methyltransferases by increasing their ability to bind to DNA and stimulating their activity[4]. Recently, tumorigenesis epigenetics is mainly involved in DNMT1 with their drug targeting. Global hypomethylation has been demonstrated in the progression of tumorigenesis with hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes and hypomethylation of oncogenes. Generally, tumor suppressor genes are silencing under aberrant hypermethylation as same as mechanism of the gene mutations resulting in the silence of tumor suppressor genes. The DNA methylation causing silencing in tumor suppressor genes typically occurs at multiple CpG sites in the promoters of protein coding tumor suppressor gene[5].

Figure 1: DNA methylation. Methylation of cytosine is a covalent modification of DNA, in which hydrogen H5 of cytosine is replaced by a methyl group under DNA methyltransferase (DNMT). In mammals, 60% - 90% of all CpGs are methylated. The pattern of methylation controls protein binding to target sites on DNA, affecting changes in gene expression and in chromatin organization, often silencing genes, which physiologically orchestrates processes like differentiation, and pathologically leads to cancer.

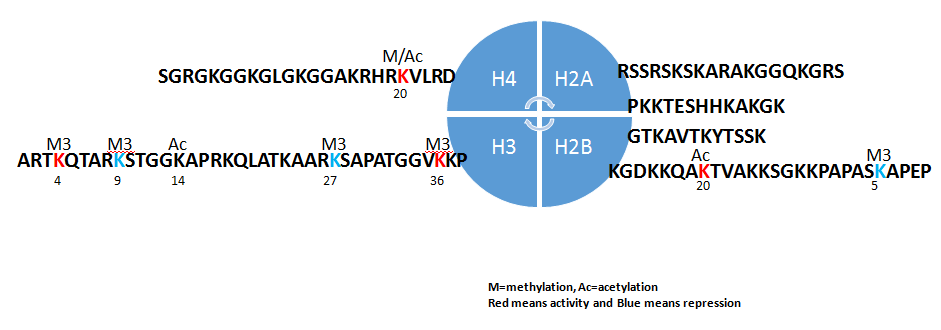

On the other hand, the second issue of epigenetics concentrates on histone modification. As Figure-2, Histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 are formed as the core histones, while histones H1 and H5 are known as the linker histones in the five major subtypes of histone family. The core histones exist as dimers, which are the histone fold domain with three alpha helices linked by two loops. The helical structure gives interaction among four distinct dimers to form one octameric nucleosome coreincluding two H2A-H2B dimers and a H3-H4 tetramer. The H2A-H2B dimers and H3-H4 tetramer are highly conserved with a ‘helix turn helix turn helix’ motif. Their long ‘tails’ are located on one end of the aminoacid structure for enzymes modifications include methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation and ubiquitination to adjust the regulatory proteins. Ordinarily, genes are active with less bound histone while inactive genes are highly bound within histones. All histones adjust regulatory proteins based on location of highly positively charged N-terminus at lysine (K) and arginine (R) residues[6].

As Table-1 and Figure-2, most positive-chargeamino acids in histone are involved in methylation to control transcription of active genes (H3K4Me3 for RNA polymerase II and H3K36Me3 for methyltransferase Set2) and that of repressed genes (H3K9me2/3 for heterochromatin protein-1, HP1 protein to recruit histone deacetylases and histone methyltransferase and H3K27me3 for polycomb complex, PCR1 and H4K20me3 for HP1)[7]. Other modification included phosphorylation of H2AX at serine 139 (γH2AX) for DNA damage and acetylation of H3 lysine 56 (H3K56Ac). Phosphorylation of H3 at serine 10 (phospho-H3S10) and phosphorylation H2B at serine 10/14(phospho-H2BS10/14) for DNA condensation. In general, tumor suppressor genes are silencing under histone methylation and oncogene are active under histone demethylation in tumorigenesis.

Figure 2: Histone post-transcriptional modification.

Histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 are formed as the core histones with some long ‘tails’ are located on one end for enzymes modifications include methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation and ubiquitination to adjust the regulatory proteins. Most well-understandable amino acids in histone in tumor diseases are H3K4Me3 and H3K36Me3 (activity, red color) and H3K9me2/3 and H3K27me3 (repressor, green color). K=lysine and R=arginine.

Table 1: Histone Post-trancriptional Modification.

| Modification | H3K4 | H3K9 | H3K14 | H3K27 | H3K36 | H2BK5 | H2BK20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tri-methylation | activation | repression | repression | activation | repression | ||

| acetylation | activation | activation | activation | activation |

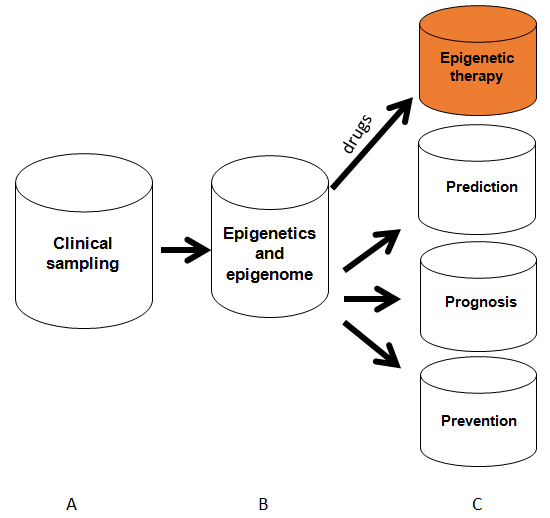

After we know DNA methylation and histone modification, according to workflow of clinical detection for epigenetics for therapeutic targeting of tumor disease, in the manual, I will systemically introduce as Figure-3 (A) clinical sampling for epigenetic analysis; (B) clinical epigenetics and epigenomics detection methods with their analyses; (C) epigenetic therapy and prevention from the epigenetics analysis; (D) in conclusion section, I will discuss challenges and future development of therapeutic targeting based on the epigenetics analysis.

Figure 3: Clinical epigenetic and epigenome analysis. Process from sampling performance, epigenome and epigenome application for epigenetic therapy and tumor prevention. Red color means epigenetic therapy which will be discussed in details in the manual.

Clinical Sampling for Epigenome Analysis

As discussed above, epigenetic aberrance with their inheritance in tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes play important roles in tumorigenesis and tumor diseases. Especially, aberrant methylation of CpG islands specific to tumor cells can be used as a marker to detect cancer cells. Methylations of specific genes or methylation patterns of groups of genes were found to be associated with indicator of epigenetic therapy and prediction of responses to chemotherapy, predictors of tumor prognosis and biomarkers of early tumorigenesis. For example, DNA demethylating agents has demonstrated to be effective for tumor diseases. Tumor tissue sampling for diagnostics and therapeutic targeting is increasingly emerging in clinics. Encouragingly, because of DNA stability from different clinical specimens, methylated DNA from non-cancerous tissues such as plasma, sera, urine and salivary fluid from tumor patients is recently attracting attention as a tumor biomarker[8]. In order to achieve good specimens for epigenetics analysis, here I will conclude two types of clinical specimens from tumor tissue specimen and non-tumor tissue specimen including their advantages and disadvantages.

Tumor cell sampling from tumor tissue

Tumor tissue sampling for epigenetic analysis includes clinical sampling in vitro; clinical sampling ex vivo and tissue level sampling with downstream clinical epigenetic analyses in silico.

1) Clinical sampling in vitro

Clinical sampling in vitro for tumor-cells isolation includes magnetic cell separation (MACS), flow-cytometric cell sorting (FACS) and Laser-Captured Micro-Dissection (LCM) with downstream epigenetic analyses[9]. MACS technique of clinical sampling in vitro is often used to sort cancer stem cells (CSC) and circulating tumor cells (CTC) by cell-surface biomarkers such as CD133/CD34 for CSCs and EpCAM for CTCs. Currently, MACS can use multi-step-labelling Abs, negatively and positively, to specifically harvest tumor cells and CTC thus it can increase its collection purity for a given tumor cells andCTC. FACS can isolate tumor cells or CSCs by a specific biomarker biomarker on the tumor cell surface as MACS but also for intracellular biomarkers which is different from MACS. At present, multi-coloured FACS can one-step collect tumor cells and CTC by combined biomarkers so that it also can enhance its purity to study epigenetic analyses from tumor cells. LCM has very good advantages relying on tumor cells morphology with their arrangement change on glass slides. LCMs have us specifically selected tumor-cells in vivo environment. Their combined Abbased staining (IHC/ICC) and DNA/RNA based staining further increase the cell specificity from their biomarkers. In these several years, following R&D of LCM techniques and biomarker identification, LCM was increasingly used in high-throughput screening biomarkers.

2) Clinical sampling ex vivo

Clinical sampling ex vivo for epigenetic analyses includes CSC or primary cancer cell culture with downstream epigenetic analyses. In 1994, we have reported 50 cases of primary tumor-cell culture for drug sensitivity assay[10]. Now we have routinely used the techniques to increase primary cell number with downstream clinical genomic analyses and drug screening so that CSC and tumor cell culture from clinical specimens with downstream epigenetic analyses will play an important role in therapeutic targeting and drug screening.

3) Tissue level sampling with downstream clinical epigenetic analyses in silico

Clinically, most of clinical specimens removed by surgery are directly frozen into liquid nitrogen at tumor tissue level. If the specimens at the tissue level are performed by epigenomics analysis, tissue level sampling with downstream clinical epigenetic analyses in silico is a very important performance for analysis of clinical epigenetic analyses because of mixed cells at the tumor tissue[11].

Liquid biopsy and body liquid sampling

Non-tumor tissue sampling for epigenetic analysis includes body liquid sampling, cfDNA, circulating tumor cell (CTC) and exosome[12]. Although exosomes contain RNA, DNA and protein, I more focus on DNA sampling and detection so that here body liquid DNA-sampling, cfDNA and CTC-DNA will be introduced in the manual.

1) Body liquid sampling

During early period from later 1990s to early 2000s, a lot of clinical laboratories have discovered that tumor cells remain in body fluids, such as urine, sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), mammary aspiration fluids, saliva and stools. When tumor cells are degraded in urine, sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), mammary aspiration fluids, saliva and stools, the DNA still remain in the liquid so that epigenetics detection have been greatly used to body liquid[13]. For examples, methylation of p16 have been analyzed in sputum; methylation of glutathione S-transferase P1 in urine; methylation of cyclin D2, RARb, Twist, GSTP1, p16, p14, RASSF1A and DAPK in mammary aspirate; methylation of p16, DAPK and MGMT in saliva; methylation of DAPK, RARb, E-cadherin, APC, RASSF1A and p14 was analyzed in urine to detect bladder cancers[14]. Following the clinical data, some commercial products have increasingly used to assay DNA alteration from patient’s body liquid samples[15].

2) Cell free DNA (cfDNA)

The cfDNA within the bloodstream is thought to originate from anapoptotic cell. Although most of this DNA is from either non-malignant cells or tumor cells, late stage cancer patients have an increased level of cfDNA in plasma. After cfDNA used to detect mutants has been extensively studied, now epigenetic aberrance are increasingly discovered[16]. CfDNA in plasma is found that size is as 50 - 180 bp as the size of histone DNA in length. The advantage of cfDNA can be analyzed from frozen and fresh plasma while disadvantages are a lower abundance cfDNA than that of CTCs from the same patient and short half-life of cfDNA in circulation and variable concentration of cfDNA, thus the yield of cfDNA remains challenges to patient application for and aberrant variants in the background of wildtype DNA[17]. In order to overcome these challenges, at least eight companies develop different products and processes to detect aberrant genes from cfDNA materials[18]. In addition, modified performance also can be used for increase cfDNA quantity. Because agitation of the sample and shipment will release cfDNA from lysed nucleated blood cells, cfDNA from plasma is much better than that from serum due to cell lysis during blood coagulation[19].

3) Circulating tumor cells (CTCs)

CTCs are cells shed into the circulation from a primary tumor location into distant organs by metastasis. Tumor cells have been increasingly detected in circulation blood from of breast, prostate, lung, and colorectal cancer patients[20]. We have been working in enriching clinical rare cells from tumor patients and genetic patients more than 20 years[21]. Clinical evidence indicates that patients with metastatic lesions are more likely to achieve CTCs up to 1-10 CTCs in each 1ml whole blood. As discussion in section above, isolating CTCs from around 10 ml blood are fundamental performance including gradient centrifuge, negative selection (CD45)/ positive selection (CD326) called as enrichment-CTC[22]. CTCs are fragile and tend to degrade when collected in standard evacuated blood collection tubes. To overcome the disadvantage, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have approved a practicable CTC tube to collect clinical sample after being drawn into the Cellsave preservative tube within 96 hours[23].

After we understand clinical sampling process for epigenetics, we need to determine which way is best to select patient specimens for downstream performance. Because tumors are highly heterogeneous, tumor tissue sampling is first desirable for personalized medicine once patients are available for their tumor samples. If physician need longitudinally monitor molecular change or clinicians need screen epigenetics alteration to detect tumor biomarkers, predict tumor prognosis and monitor response to tumor treatment, liquid biopsy is first choice because it is easily accessible and minimally invasive as shown in Table-2[24].

Table 2: Clinical Sampling for Epigenetics analysis.

| Tumor tissue level | Non-tumor level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methods | Sampling in vitro | Sampling ex vivo | Tumor tissue | Body liquid | cfDNA from Liquid biopsy | CTC-DNA |

| Clinical application | Precision medicine for treatment | 1. Monitor epigenetics during treatment; 2. Prevention; 3. Prediction | ||||

| Advantages | Specificity and sensitivity for precision medicine | An easily accessible, minimally invasive way | ||||

Clinical Epigenetic Detection and Epigenome Analysis

Clinical analysis for DNA methylation

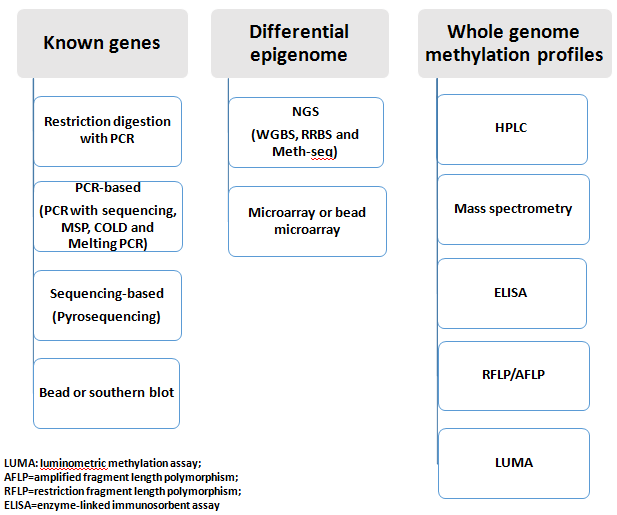

Quantifiable and feasible DNA methylation detection is a very important view for clinical application. Currently, technologies to detect DNA methylation have been tremendously applied into clinical research after the past 30 years’ development, almost all techniques can cover methylation detection as Figure-4. Some scientists classify the methylation analysis as A: global measures of DNA methylation, B: local specific genes and C: genomic regions and global measurement at a genome-wide scale based on sequencing technology and microarray[25]. In clinical application, any epigenetic assay requires three considerations, feasibility of assay-method, initial workflow from known-gene epigenetics and initial workflow from unknown-genes epigenome listed as below:

Figure 4: Epigenetic and epigenome research technique. Alltechnologies to detect DNA methylation are classified: A. local specific genes which have successfully employed in both research lab and clinical fields; B. genomic regions and global measurement at a genome-wide scale based on sequencing technology and microarray which have successfully used in both research and clinical fields; C. global measures of DNA methylation which is often applied for research lab or clinical lab with the equipment.

1) Feasibility for DNA methylation detection

Clinically, feasible results of clinical diagnosis depend on of choice of methodology including A: the amount and quality of the DNA sample such as DNA from Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) or from liquid biopsy; B: a method of sensitivity and specificity for clinical epigenetics; C: the robustness and simplicity of the assay method and the availability of specialized equipment, reagents and bioinformatics software. Beyond the three requirements as above to detect methylation, the clinical workflow also should be considered either (I) initial workflow from discovery of de novo epigenetic changes or (II) initial workflow to the specific genes for monitor the methylation change.

2) Initial workflow from known-genes epigenetics

If we have known the some epigenetic aberrance in some tumor diseases, initial workflow are very practicable process from known-genes. At present, all PCR-based, pyrosequencing, restriction digestion enzyme assay can be used to detect known gene epigenetic alteration[26]. Although we had reported restriction digestion enzyme assay[27], according to clinical requirement as feasibility and reproducibility, here I just introduce two techniques based on available products from company.

PCR-based methylation detection

Currently, there at least four PCR-based methylation detection are often used in clinical fields: PCR-based sequencing, Methylation-Specific PCR, PCR with High Resolution Melting and COLD-PCR for the Detection of Unmethylated Islands. PCR-based sequencing first performed PCR in which primers are designed around the CpG island (MethPrimer software at http://www.urogene.org/methprimer) and thus used for PCR amplification of bisulfite-converted DNA. The resulting PCR products could be sequenced. Until recently, this was the only way to demonstrate the methylation status of individual CpG sites within the CpG islands of interest[28]. Another method that uses bisulfite-converted DNA is methylation-specific PCR. To detect methylation, two pairs of primers are designed: one pair amplify methylated DNA and another amplify unmethylated DNA. Two qPCR reactions are performed for each sample and thus relative methylation is calculated relied on the difference of their Ct values[29]. The drawback is that methylation status of only one or two CpG sites is assessed at a time. The program for the design of methylation-specific primers can be found at (http://www.urogene.org/methprimer). PCR with High Resolution Melting and COLD-PCR are often applied in research experiments for the detection of unmethylated Islands.

Sequencing-based methylation detection

Pyrosequencing is known-gene detection technology. Individual gene primers are designed or purchased from PyroMark CpG Assays from Qiagen. After PCR products are obtained, short-read pyrosequencing reaction (~100 bp) is performed. Because signal intensities for incorporated dGTP for methylated CpC and dATP for unmethylated DNA, the level of methylation for each CpG site is quantified within the sequenced region. The technique is able toassay very small aberrance in methylation (< 5%). It is a good technique for heterogeneous tumor samples in which only a fraction of cells in mixed cells has a differentially methylated gene aberrance. Pyrosequencing requires some equipment to detect, such as the Qseq instrument from Bio Molecular Systems or PyroMark from Qiagen[30].

3) Initial workflow from unknown-genes to discover epigenomic aberrance:

In the early periods, we had routinely used random restriction enzyme digestion with fingerprint to discover aberrance at DNA genome level with SNPs and epigenome level with methylation in the precancerous tissue[31]. Now all we are going into genome era, we can use genomic technique to uncover hypermethylation in the new tumor suppressor genes. Current methods for identification of differentially and unknown methylated regions include Next-generation sequencing (NGS) and microarray techniques as below.

NGS-based detection

Currently, bisulfite Sequencing is thought to be the better method to detect clinical DNA methylation aberrance. Because the bisulfite treatment of DNA can transform cytosine into uracil and then convert as thymine, 5mC residues are resistant to this conversion and thus methylated DNAs remain cytosine and then into guanine. Thus, sequencing read from a pair of an untreated DNA sample and bisulfite treated same sample enables the detection of the methylated cytosine. Following the advent of NGS technology, this approach can be extended to DNA methylation analysis (called as whole genome bisulfite sequencing, WGBS) across an entire genome. To increase the sequencing coverage discovering differentially-methylated regions, enrichment methods also have been developed such as anti-methylcytosine binding proteins (MBD) or antibodies against 5 mC (MeDIP) to enrich methylation DNA. After those development, another NGS method (called as reduced representation bisulfite sequencing, RRBS) is used to sequence to increase coverage due to only with the fraction in the genome. Sequencing could be done using any available NGS platform such as Illumina and Life Technologies with isolation of ~85% of CpG islands in the human genome performed as for WGBS. The RRBS procedure normally requires about 0.1ug~1 ug of DNA after successful MspI digestion[32]. Recently, another enrichment for CpG-rich regions or specific regions from Agilent can use bait sequences to hybridize immobilized oligonucleotides and then bisulfite conversion. Such products are commercially available(e.g., SureSelect Human Methyl-Seq from Agilent and is called targeted bisulfite sequencing (Methyl-seq)[33].

Array-based detection

Methylated DNA of the genome obtained by immunoprecipitation could be used for hybridization by microarrays. At present, at least three companies support microarray chips or beads, such as the Human CpG Island Microarray Kit from Agilent and the GeneChip Human Promoter 1.0R Array and the GeneChip Human Tiling 2.0R Array Set from Affymetrix[34]. These arrays can use bisulfite-converted DNA to detect DNA methylation within gene promoter regions, enhancer regulatory elements and31 untranslated regions (31UTRs). The Infinium HumanMethylation450 Bead Chip from Illumina can detect 485,000 individual CpG from 0.5 ug input DNA in 99% known genes including miRNA promoters, 51 UTR, 31 UTR, coding regions (~17 CpG per gene) and island shores (regions ~2 kb upstream of the CpG islands).Technically, bisulfite-treated genomic DNA is mixed with assay oligos, one is complimentary to uracil from original unmethylated cytosine and another is complimentary to the cytosine of the methylated site. With hybridization, labelled assay oligos are immobilized to bar-coded beads and the signal is measured for its methylation level. Because the price is about U.S. $ 300 – 360/sample so that the chips still are often used in the study of human epigenetic aberrance.

Clinical analysis for histone modification

Defects in histone posttranslational modification (PTM) have been linked to human tumor although histone markers will be under investigation. In research fields, the protocol includes nuclear extract, histone purification and histone enrichment. The production of site-specifically modified histones, peptide-based systems to characterize PTM-binding proteins and histone modifications by specific PTM antibodies, in vivo histone modifications imaging and different methods to analyze chromatin immunoprecipitation samples. For example, if we study a histone PTM from a clinical specimen, we first process whole-cell lysates and extraction, histone-enriched fractions and purified histone proteins, histone PTM detection by antibody recognition for both tumor tissue and normal control. Recently, 200 antibodies against 57 different histone PTM are available[35]. In the other hands, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) can detect genomic location for specific PTM histone. Accompany with techniques of PCR, microarray and NGS, determination of the genomic loci for specific PTM histone is called as ChIP assay (with downstream PCR), ChIP-chip (with downstream microarray) and Chip-seq (with downstream NGS)[36]. At present, development for clinical specimen to assay PTM histone is not as easy as detecting DNA methylation. One successful example is ChIP-seq analysis from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples[37]. Although histone modification assay is slowly developed into clinical analysis and diagnosis, histone PTM detection by mass spectrometry (MS) have shown a feasible feature in identifying and quantifying histone PTMs for clinical analysis. More recently, MALDI imaging mass spectrometry has been used to detect variants histone PTMs from patient tissues so that MALDI imaging mass spectrometry in situ should be used in clinical analysis in the near future[38].

Clinical Application from Epigenetic Data

As saying epigenetic aberrations and epigenome can guide physicians several strategies for clinical application[39,40]. In order to understand these strategies, here, I conclude almost all clinical employment including (A) epigenetic therapy and (2) tumor prediction, prognosis and tumor prevention.

Epigenetic therapy

After aberrant epigenetics is discovered, drug discovery depends on their linkage between drug-bank and epigenetic aberrance discovered from the patients.

1) Epigenetic therapy based on methylation assay

DNA methylation is increased in silencing of tumor suppressor genes that control cell growth. If epigenetic aberrance is discovered, the aberrant DNA initiate the normal cell into malignancy. This progress can be removed by agents such as 5-azacitidine (AZA) and decitabine (DEC) by DNMT1 inhibition[41]. Because DNMT1 inhibitors have lower toxic to tumor cells, currently, three strategies are used to increase DNMT1 inhibition: (A) low-dose AZA or DEC treatment can induce long-lasting decreases in tumorigenesis of tumor-initiating cells without cytotoxicity in cell cycle. This slow onset of therapeutic responses to demethylating agents have been successfully reported in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia with persistent response after therapy[42]. (B) A demethylating agents (AZA and DEC) could activate genes encoding MHC class I genes and tumor antigens. For example, interferon pathway genes were reported to upregulate by AZA administration and thus AZA was correlated to increase expression of endogenous antigen presentation and interferon response. Furthermore, some physicians provide evidence that inhibition of DNA methylation could sensitize melanoma to anti-CTLA4 immune checkpoint therapy and immunosuppressive PDL1. More recently, AZA was found to increase the development of immunosuppressive Treg cells in vitro and in patients with myeloid malignancy[43]. (C) A combination of AZA with a histone deacetylase inhibitor can increase the tumor suppressor reactivation[44]. All of the results demonstrate that epigenetic therapy by anti-DNMT will be effective model to treat different tumors as Table-3.

Table 3: Clinical Epigenetics Therapy.

| Type | Epigenetic therapy | Antitumor | FDA approved |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMTI | decitabine | MDS/AML | 2006 |

| Azacitidine | MDS/AML | 2004 | |

| zebularine | MDS/AML | not yet | |

| HDI | Vorinostat | cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) | 2006 |

| Romidepsin | CTCL | 2009 | |

| Chidamide | peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) | 2015 China | |

| Panobinostat | multiple myeloma | 2015 | |

| Belinostat | T cell lymphoma | 2014 |

2) Epigenetic therapy based on PTM histone assay

Histone control the coiling and uncoiling of DNA with the assistance of HAT while the actions of HDAC remove the acetyl groups from the lysine residues leading to the formation of a condensed and transcriptionally silenced chromatin[45]. The reversible modification of the terminal tails of core histones programs the major epigenome mechanism for controlling gene expression. HDAC inhibitors (HDI) block this action and can result in hyperacetylation of histones so that HDIs are a new class of agents to inhibit the proliferation of tumor cells. HDI make an anti-tumour effect by the induction tumour suppressor such as P53 protein. Recent years, there has been an effort to develop HDIs as an option for tumor treatment. HDI can induce p21 expression, a regulator of p53 activity. HDACs are involved in retinoblastoma protein (pBb) pathway by which the pRb suppresses tumor proliferation. Estrogen is a factor demonstrated in tumorigenesis. Progression of breast tumor byits binding to the estrogen receptor alpha (Era) data indicatesthat DNA methylation is a critical component of ERα silencing in human breast cancer cells. Because HDI inhibiting HDAC have very effectivetoxic to tumor cells, currently, several HDIs are applied for hematological malignance, breast and lung cancers as Table-3[46].

Epigenetic aberrance for tumor prediction, prevention and prognosis

Prediction of Epigenetic Aberrance

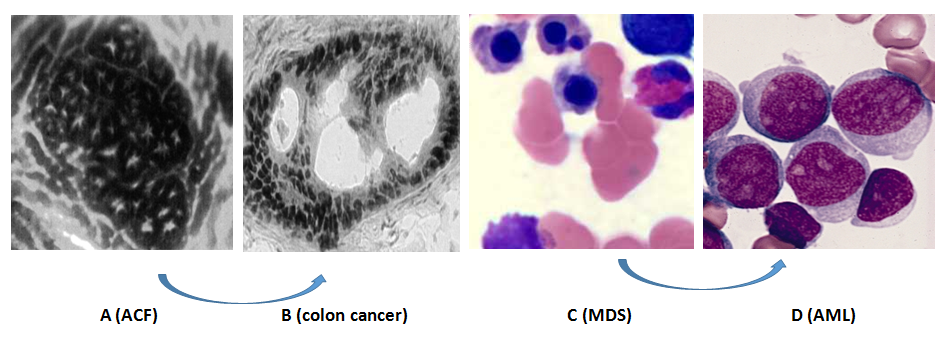

In order to observe development from precancerous cells into cancer cells, in early periods, we made great effort to study clinical model including hematological malignance from myelodysplasia syndrome (MDS) into Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) and solid tumor from aberrant crypt foci (ACF) into colon cancer (Figure-5 and Table-4). In the clinical models, Dr. Preisler’s lab early defined p15 methylation as biomarker for hematological malignance in precancerous periods with comparison among 128 MDS and 44 AML to 12 normal bone marrow[47]. Now p15 hypermethylation have been routinely used in screening and predicting the development of hematological malignance. After more than twenty year’s development, more precancerous lesions are discovered such as epithelial dysplasia/ intraepithelial neoplasia in stomach, intestinal metaplasia, Barrett’s esophagus, breast calcifications, mono gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS), vulvar intra-epithelial neoplasia (VIN), vaginal intra-epithelial neoplasia (VAIN), vulvar lichen sclerosis and lichen planus, cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN) and Bowen’s disease[48]. Although epigenetic aberrant hMLH1 and H19/Igf2 clearly demonstrated to sporadic or familial cancers, most precancerous lesions will be regressed, thus very small number of precancerous cells will develop into malignant tumors so that methylation tests of these genes should be carefully evaluated by epigenetic aberrance. As demonstrated at Table-5, p16 methylation was detected in most of precancerous disease, methylation of HPP1 and RUNX3 correlates with progression of Barrett’s esophagus, p15 methylation was detected in most of MDS disease and p14 methylation is associate with colorectal dysplasia lesions from patients with ulcerative colitis. Following new detection technique of methylation alteration, more and more methylation genes were discovered in different precancerous tissue. For example, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) was discovered in NSCLC tissues[49]. Before genomic periods, we have made great efforts to uncover some new methylation at whole genomic DNA level, Dr. Pretlow and I had used random restriction enzyme digestion with finger print techniques at genome level to discover some new methylation from ACF tissue as Figure-5(A-B)[50]. Now we all are going into genome era, we can use genomic technique to uncover the new methylation location located at tumor suppressor genes as Figure-6.

Figure 5: Tumorigenesis from precancerous cells into cancer cells.

Figure 5A is aberrant crypt foci (ACF) in colon and Fig. 5B is colon cancer tissue in which both A and B is a clinical model from precancerous cells into cancers from solid tumor and Fig. 5C are MDS cells and Fig. 5D are AML cells in which both clinical tissues are our early model to study tumorigenesis from precancerous hematological cancer into malignant hematological cancer cells.

Table 4: Biomarker for Epigenetics Analysis.

| Types of Biomarkers | Indicator | Methylation genes |

|---|---|---|

| Universal biomarkers | Universal tumor suppress genes | p53 |

| Susceptibility prediction | Normal cells susceptible for tumorgenesis | hMLH1, H19/Igf2 |

| Transformation markers | Precancerous cancer | p16, p15, p14, FZD9 |

| Diagnostic markers | Early tumor diagnosis | Septin9 |

| Prognostic markers | Advanced tumor prognosis | APC, DAPK, LINE-1, H3K9, H3K18Ac |

| Chemosensitivity markers | Tumor responses for chemotherapy | MGMT, hMLH1, BRCA1 |

Table 5: Prediction Biomarkers for Epigenetics Analysis.

| Genes of methylation | Location | Tumor prediction |

|---|---|---|

| p16 | 9p21 | lung, liver, and glandular stomach |

| hMLH1 | 3p21.3 | hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer |

| H19/Igf2 | 11p15.5 | pediatric diseases (SRS, BWS, PWS, Angelman syndrome) |

| p15 | 9p21.3 | MDS, AML |

| HPP1 | 19pter-p13.1 | progression of Barrett’s esophagus |

| RUNX3 | 1p36.11 | progression of Barrett’s esophagus |

| p14 | 9p21.3 | colorectal dysplasia lesions |

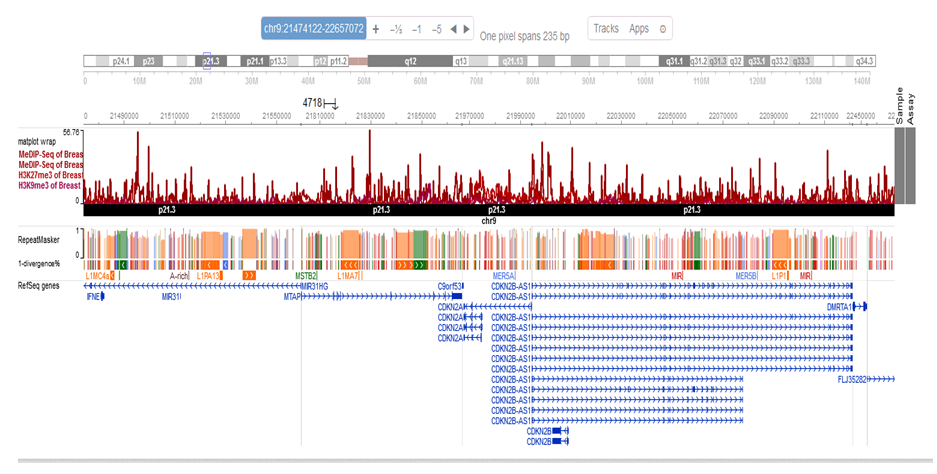

Figure 6: Epigenome Data

After we harvested PTM histone-seq from precancerous breast tissue, a p15 region was analyzed to study H3K9Me3 and H3K27Me3 PTMhistone (both are repressing to p15 suppressor gene). Results demonstrated hypermethylation p15 region in chromosome 9 from 21474122 bp to 22657072 bp.

1) Prognostic Markers from Epigenetic Aberrance

Advanced cancer is the main cause of human death because of resistance of chemotherapy/radiotherapy, recurrence, remote metastasis of tumors (3R). Identification of reliable prognostic factors including tumor resistance, recurrence and remote metastasis (3R) could have significant anticipation for clinical cancer patients. For example, patients with high-risk resistance of chemotherapy/radiotherapy need adjust new strategies while patient with low-risk without 3R should use routine administration. The prognostic biomarkers mainly include histologic phenomenon, cell proliferation, hormones expression, and molecular biomarkers including epigenetic and genetic aberrance as Table-6. In order to clearly understand the biomarkers, we have studied 25 patients’ bone marrow cells with poor prognosis AML to characterize and to assess the biomarkers related with treatment. The panel of biomarkers included high levels of telomerase activity, low levels of IL6 expression, p53 mutation and p15 hypermethylation. After drug screening, finally the effects with comprehensive treatment with the poor prognosis demonstrated reducing telomerase activity, increase IL6 and decrease p15 methylation resulting in good response for the refractory AML and increase of patient survival[51]. Now, aberrant DNA methylation of CpG islands can be measured almost every type of tumor. Most of these prognostic markers have been grouped as such as death-associated protein kinase gene (DAPK), LINE-1, p16, and APC[52]. For example, epigenetic changes from NSCLChave been linked to recurrence and methylation of TP16, CDH13, RASSFIA, and APC. Some physicians classified 138 lung cancer patients into seven groups based on histology, stage, and global expression levels of H3K4Me2, H2AK5Ac, and H3K9Ac[53]. The groups showed that high intratumoral levels of H3K4Me2 reltae with significant improvement in overall survival compared to patients with high intratumoral levels of H3K-9Ac.

Table 6: Prognosis Biomarkers for Epigenetics Analysis.

| Tumor disease | Methylation genes | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|

| Acute myeloid leukemia | ER | Improved survival |

| Bladder cancer | RAR/3 | Invasion |

| RASSF2 | Poor survival | |

| RUNX3 | Invasion, poor survival | |

| TIMP3 | Metastasis | |

| Breast cancer | hMLH1 | Metastasis and poor survival |

| Colorectal cancer | HLTF | Recurrence, poor prognosis |

| ID-4 | Poor survival | |

| p16 | Lymphatic invasion | |

| Vimentin | Liver metastasis | |

| Esophageal cancer | APC | Poor survival |

| Gastric cancer | CDH2 | Recurrence |

| COX2 | Improved survival | |

| FHIT | Node metastasis | |

| p17 | Metastasis | |

| Glioma | ASC/TMS2 | Poor survival |

| MGMT | Poor survival | |

| Melanoma | FHIT | Advanced stage |

| Neuroblastoma | RASSF3 | Poor survival |

| NSCLC | APC | Poor survival |

| ASC/TMS1 | Invasion | |

| CDH1 | Longer survival | |

| DAPK | Poor survival | |

| FHIT | Poor survival | |

| GSTP3 | Poor prognosis | |

| IGFBP3 | Poor prognosis | |

| MGMT | Poor survival | |

| RASSF1 | Recurrence | |

| Ovarian cancer | RASSF4 | Invasion |

| Prostate cancer | CD44 | Metastasis |

| ESR1 | Progression | |

| GSTP1 | Recurrence | |

| GSTP2 | Advanced stage | |

| LAMA3/B3/C2 | Poor survival | |

| LINE-1 demethylation | Metastasis | |

| PTGS2 | Poor prognosis | |

| SLC18A2 | Poor survival |

On the other hand, a second type of prognostic biomarkers is an estimation of the response of treatments[54]. For example, the methylation MGMT gene is a predictor of chemosensitivity to alkylating agents in gliomas. MGMT locates in the chromosome 10q26 region with low expression of MGMT under physiological condition, but upregulated after exposed to alkylating agents or radiation. MGMT over expression protects normal tissues from the toxic effects of alkylating carci-nogens including chemotherapy agents. Because functions of MGMT are the DNA repair, BCNU and carmustine are indicators for chemosensitivity and radiation to malignant gliomas and glioblastoma if we find MGMT hypermethylation. Additionally, the methylation predicting the response to chemotherapy has been reported between cisplatin and methylation of gene hMLH1 in ovarian tumor, between tamoxifen and BRCA1 methylation in breast tumor, between irinotecan and WRN methylation. Here I briefly summarize the information related to chemosensitivity as Table-7.

Table 7: Prognosis Biomarkers for Drug Response

| Cancer type | Gene Methylation | Associated characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | ABCB1 and GSTP1 | Increased sensitivity to doxorubicin |

| BRCA1 | Increased sensitivity to cisplatin | |

| CDK10 | Increased resistance to tamoxifen | |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | LINE1 demethylation | Increased sensitivity to decitabine |

| Endometrial cancer | CHFR | Increased sensitivity to taxanes |

| Gastric cancer | ASC/TMS1 | Increased resistance to 5-fluorouriacil |

| CHFR | Increased sensitivity to microtubule inhibitors | |

| Germ cell tumor | RASSF1A and HIC1 | Increased resistance to cisplatin |

| Glioma | MGMT | Increased sensitivity to carmustine |

| Ovarian cancer | BRCA1 and BRCA2 | Increased sensitivity to cisplatin |

| hMLH2 | Increased resistance to carboplatin/taxoid | |

| Werner syndrome | WRN | Increased resistance to irinotecan |

2) Prevention Therapy for Early Markers from Epigenetic Aberrance

Currently most of tumor prevention is involved in type of activity, kind of nutrient or dietary and weight control. The preventative measures must be taken a long time to give results that can be examined so that no guarantee eating or behaving in a certain way will absolutely assure freedom from cancer development. Here we address a tumor prevention by early screening cancer, or an effort to set efficient and noninvasive molecular tests to detect aberrant epigenetics to link tumor methylated DNA markers from non-invasive methods[55]. For example, circulating Septin9, vimentin, TMEFF2, NFGR methylation may become a biomarker for screening early primary colorectal cancers (CRC). A few potential methylation candidates such as GSTP1 for prostate cancer and ALX4 for bladder cancer are emerging for detection of cancers at early stages as Table-8. Following epigenomic screen emerging, more hypermethylation genes will be discovered in the early cancer detection.

Table 8: Prevention and Treatment Biomarkers of Early Tumor.

| Gene methylation | Early tumors | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Septin9 | CRC | 17q25.3 |

| vimentin | CRC | 10p13 |

| TMEFF2 | CRC | 2q32.3 |

| NFGR | CRC | 17q21 |

| GSTP1 | Prostate cancer | 11q13.2 |

| ALX4 | Bladder cancer | 11p11.2 |

| HIC1 | Liver cancer | 17p13.3 |

| GSTP1 | Liver cancer | 11q13.2 |

| SOCS1 | Liver cancer | 16p13.13 |

| RASSF1 | Liver cancer | 3p21.31 |

| CDKN2A | Liver cancer | 9p21.3 |

| APC | Liver cancer | 5q22.2 |

| RUNX3 | Liver cancer | 1p36.11 |

| PRDM2 | Liver cancer | 1p36.21 |

Conclusion

Epigenetic detection is a new clinical model to assay aberrant DNA methylation and histone PTM. To prevent tumorigenesis and treat tumor patients, we need patient information including epigenetic detection. Although detecting aberrant DNA methylation and histone PTM has been quickly developed during last twenty years, several questions still should be addressed as below:

1) Epigenome for quantitative network support

Genomics-based diagnostic tests have been greatly developed in direct therapeutic interventions. In order that clinical trials improving clinical practice are used by clinical genomic analysis, quantitative network supporting clinical genomic diagnosis have been tremendously developed to provide personalized treatment for patients[56]. As I discussed above, in order to improve effects for epigenetic therapy for tumor patients, we need to develop quantitative network from epigenome data for define specific therapeutic targeting.

2) Clinical epigenetic diagnoses require routine specificity and sensitivity test

As we performed specificity and sensitivity from the genomic profile[57], we also need set up specificity and sensitivity test from epigenome profile. If we add both clinical tests, clinical epigenetic therapy should be greatly improved.

3) Clinical epigenetic diagnoses require confirmation test

Recent development of cancer research has enabled scientists to use different epigenetics profiles for patient application. If we add lab confirmation assay, clinical epigenetic diagnosis and therapy should be greatly improved[58].

4) Epigenetics demand to develop other options

After epigenetic aberrance discovered, currently FDA approved compounds were used for clinical development of targeted therapy at the bedside. If we combine GWAS, RNA genomics or microRNA profiles related with drugs, Ab and small molecules[59,60], clinical genomics should be greatly improved in epigenetic diagnosis and therapy.

Acknowledge:

Under the support of Dr. H. D. Preisler, we had set up the method to analyze clinical genomic analysis including single-cell genomic profiles of tumor cell from solid tumors and leukemia. Now we are going to use new genomic platform to continue working in epigenetic aberrance. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this article is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare non-competing financial interests.

References

- 1. Baker, S.J., Markowitz, S., Fearon, E.R., et al. Suppression of human colorectal carcinoma cell growth by wild-type p53. (1990) Science 249(4971): 912-915.

Pubmed || Crossref - 2. Chial, H. Proto-oncogenes to Oncogenes to Cancer. (2008) Nature Education 1(1): 33.

- 3. Ledford, H. Disputed definitions. (2008) Nature 455(7216): 1023-1028.

Pubmed || Crossref - 4. Rountree, M.R., Bachman, K.E., Baylin, S.B. DNMT1 binds HDAC2 and a new co-repressor, DMAP1, to form a complex at replication foci. (2000) Nat Genet 25(3): 269-277.

Pubmed || Crossref - 5. Cohen, N., Kenigsberg, E., Tanay, A. Primate CpG Islands Are Maintained by Heterogeneous Evolutionary Regimes Involving Minimal Selection. (2011) Cell 145(5): 773-786.

Pubmed || Crossref - 6. Cuthbert, G.L., Daujat, S., Snowden, A.W., et al. Histone deimination antagonizes arginine methylation. (2004) Cell 118(5): 545-553.

Pubmed || Crossref - 7. Ozdemir, A., Spicuglia, S., Lasonder, E., et al. Characterization of lysine 56 of histone H3 as an acetylation site in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. (2005) J Biol Chem 280(28): 25949-25952.

Pubmed || <a hr