Water H2O2 Levels as Factor in Swimmers Melanoma

Affiliation

Citizen Scientist, 13442 SW 102 Lane, Miami, Florida, USA

Corresponding Author

Abraham A. Embi, Citizen Scientist, 13442 SW 102 Lane, Miami, Florida, USA, 33186, E-mail: embi21@att.net

Citation

Embi, A.A. Water H2O2 Levels as Factor in Swimmers Melanoma. (2018) Lett Health Biol Sci 3(1): 1- 4.

Copy rights

© 2018 Embi, A.A. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

H2O2; Oxidative Stress; Swimmers Melanoma; Pig Melanoma Formation; Biophysics cancerogenesis

Abstract

Introduction: This study proposes afoundation which could demonstrate a published H2O2 hypothesis of cancerogenesis. A mechanism explaining the high incidence of melanoma in swimmers is described.

Methods: Humanhairs immersed in drops of pure water with resistivity of 18.2 MΩ × cm (million ohms) were in indirect contact with adjacent drops of 35% H2O2. Digital microphotographs and video-recordings were obtained for further analysis.

Results: This approach allows visualization of details that could not be analyzed previously. The findings show that H2O2 penetrates hair follicles either at the sites of injury to external structures or at the intact shaft/skin junction.

Conclusions: In hairs immersed in pure water mixed with a low concentration of H2O2, sebum and contiguous dermal sheaths blocked exogenous H2O2. Conversely, in injured hair follicles and at the intact shaft/skin junction, H2O2 penetrated the tissue and was subsequently decomposed by catalase. This mechanism is proposed for the high incidence of Swimmers Melanoma.

Introduction

Analytical measurement of the effects of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) on tissues has been difficult[1]. The objectives of the present study are to introduce an experimental method to reduce H2O2 substrate concentration in solutions in contact with human hair follicles; thus mimicking surface fresh and saltwater H2O2 levels. A second objective is to demonstrate the protective role of the external skin layers from penetration of reactive oxygen species (ROS), namely H2O2.

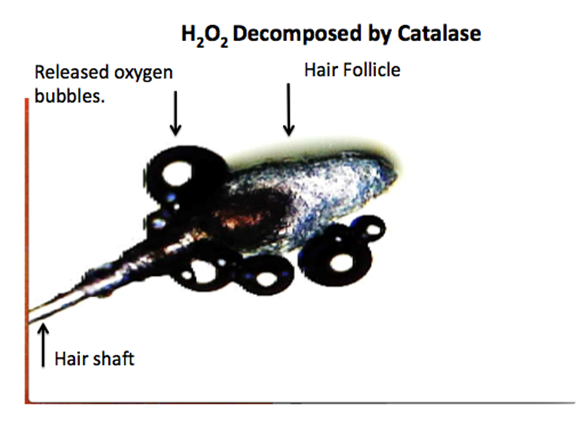

One factor impeding optical microscopy studies of the effect of H2O2 decomposition on tissue is the rapid decomposition caused by the enzyme catalase. Invariably, multiple layers of gas bubbles rapidly form, obstructing the viewing field (Figure 1). Reports of “swimmers melanomas” in adults and children, as well as reports of H2O2 formation resulting principally from the excitation of humic substances in fresh and sea water by the ultraviolet (UV) portion of sunlight, have been published[2,3]. These studies raise the question of whether H2O2 present in surface waters is a risk factor for the development of melanoma in swimmers.

Successful attempts to suppress the rate of H2O2 decomposition reaction utilizing activated carbons have been described[4]. The hair follicle has been described as a dynamic miniorgan[5] with independent cell division and differentiation and adjacent sebaceous gland, as well as dermal sheaths[6]. H2O2 vapors are air-bound and used for bio-decontamination through deposition on surfaces via micro-condensation[7]. This manuscript introduces a simple method to use the human hair follicle as sentinel following immersion in pure water to slow down the explosive repetitive decomposition of H2O2.

Figure 1: Microphotograph of 3% H2O2 spontaneous reaction with a hair follicle. Numerous oxygen bubbles obscuring the viewing field. See link for video-recording. https://youtu.be/c-wrQdPK2pk

Materials and Methods

Glass slides (25 × 75 × 1 mm, #1301) were purchased from Globe Scientific Inc. Certified food grade H2O2 (35%) and bovine liver liquid catalase (purified, thymol-free) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (StockC-40, one gram 11000 units).Very pure water with resistivity of 18.2 MΩ × cm (million 112 ohms) supplied by The University of Oklahoma, Health Sciences Center. was used. The equipment included a model OS425-LS non-contact infrared thermometer, Celestron model 44348 digital video microscope, 117 Acurite model 01538CDI remote weather station, Apple Mac Book computer, and Apple Inc. iPhoto 8.1.2 application.

Harvesting and mounting of hair samples

Sixteen hairs were plucked from the scalp of the author using tweezers. Care was taken to select hairs with large visible roots. Using a fresh double-edge razor blade, ten of the hair follicles were gently injured after placing on a dry slide. This maneuver produced four partially transected follicles with different follicular injury patterns. The individual hairs (12 intact and 4 injured) were individually placed on the center of clean glass slides then covered by two drops of very pure water with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ × cm. Two to three drops of 35% H2O2 were delivered via a micropipette to the same slide 4 to 5 mm distant from the pure water drops. Care was taken not to mix the drops. Each preparation was mounted on a digital video-microscope platform and observed for any changes of the hair follicles. Gas bubbles emanating from the hair follicles appeared slowly on the hair tissue. Once the slow bubbling started after approximately 8 ± 3 minutes (Figure 1A), microphotographs and video-recordings were obtained and the data were stored for subsequent analysis. Ancillary testing demonstrated the gradual transfer of H2O2 into the pure water drops.

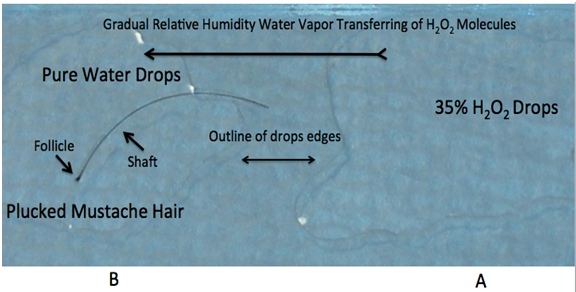

Figure 1(A): A = Drops of 35% H2O2 on right side of glass slide B = Plucked mustache hair in pure water drops Long black arrow showing theorized gradual transfer of H2O2 molecules penetrating pure water drops.

Results

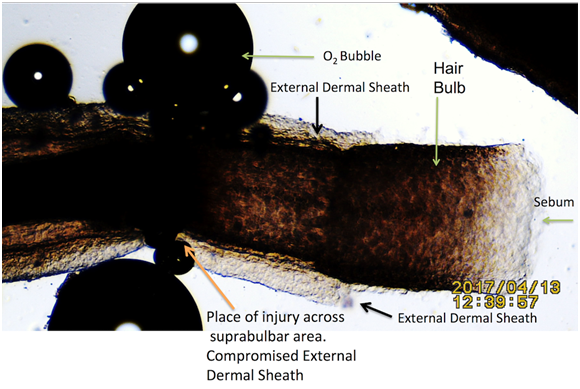

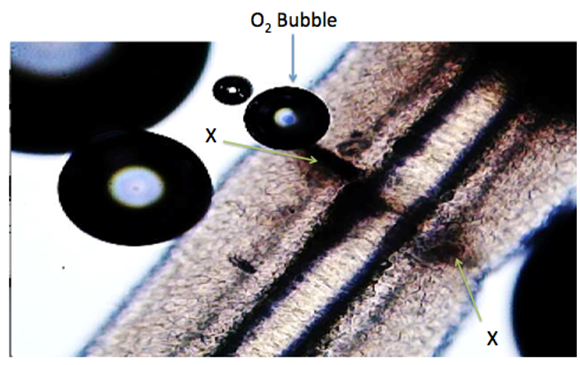

All intact follicles showed bubbling activity; it occurred near the shaft/skin boundary in 12 follicles (Figure 2 & 3) and Supplementary Video #0043) and at the bulb and suprabulbar external areas in the four injured follicles In all the injured follicles, O2 gas was observed to be flowing slowly between the cortex and medulla, exiting at the injury site (Figure 4 & 5).

Figure 2. Showing O2 bubbles emanating from the hair follicle/epidermis junction. Subsequent research (not shown) showed the bubbles originating from inside the distal shaft (not from the epidermal tissue). Please click on video link: https://youtu.be/09tYp348jKM

Figure 3: Microphotograph of video-frame from another experiment On the top surface of the SDW, a human peri-umbilicar hair was immersed in purified water. The H2O2 molecules transferred via water vapor (See Figure.1) were decomposed by the catalase present at the hair shaft/skin junction. Oxygen bubbles (arrow) are seen released by the hair follicle. Note: Notice hair shaft free of O2 bubbles.

Figure 4: Injured hair follicle at mid bulb area showing place of O2 bubbles origin. Hair immersed in pure water adjacent to drops of 35% H2O2. Black Arrows: External Dermal Sheath (EDS). Notice the absence of oxygen bubbles in areas protected by the EDS and sebum.

Figure 5: Transverse injury to another hair follicle via double edge razor blade X = Injured Tissue. Microphotograph of video-frame showing O2 bubbles forming due to H2O2 molecules penetrating the pure water. The H2O2 decomposition caused by the protein enzyme catalase present in the hair follicle. The follicle’s outer wall (sebum) integrity was disrupted by trauma, thus allowing penetration of the H2O2 molecules. Click on link for video-recording: https://youtu.be/qRlV43Zphvc

H2O2 water vapor transfer

Water vapor is known to transport molecules (including H2O2).

Concerning the cause(s) of the observed slow H2O2 decomposition by the hair follicles, it could be theorized that H2O2 molecules gradually penetrated the pure water adjacent to the 35% drops of H2O2 adjacently placed on the same glass slide as shown in Figure 1A.

Discussion

Oxidative stress due to tissue metabolism in hair follicles has been previously demonstrated[11,12]. Hair follicles produce catalase in order to decompose ROS and achieve homeostasis. The present findings were possibly due to the very slow bubbling observed during the endogenous catalase-mediated decomposition of H2O2 that penetrated the hair follicles.

The first thought was that the presence of catalase in the scalp[13] could be the cause of the intense bubbling observed at the shaft/skin junction site. High magnification views showed that the bubbling originated away from the shaft/skin boundary surface. Since the shaft/skin junction area was uninjured, the observations prompted the consideration of whether the shaft/skin junction area in the skin was a point of spontaneous entry for H2O2.

Sebum/Dermal sheaths as barriers

Observed was that exogenous H2O2 penetrated deep into hair follicles. In seeking a mechanism for this observation, it was noted that when hair follicles were injured, the protective sebum coat and dermal sheaths were compromised (Figure. 6). This would allow the exogenous H2O2 to penetrate the internal tissue layers where it would be decomposed by the ubiquitous enzyme catalase.

The present study also presents an association of sebum combined with intact dermal sheaths acting as a barrier to ROS external toxicity.

Figure 6: Plucked Beard hair mounted on glass slide- Black arrows showing A= Outer layer showing lipids globules B= Intact External Dermal layers.

Summary and Conclusions

Swimmers melanoma

Two decades ago, it was postulated that the recreational exposure to sunlight did not fully explain the current trends In melanoma Incidence[14]. The authors suggested that the “positive association between a history of swimming and melanoma risk suggests that carcinogenic agents in water, possibly chlorination by products, play a role in melanoma aetiology”. Additionally, considering the skin dryness of swimmers, the same authors stated that this is “caused by a combination of the dilution of natural sebum and by the osmotic gradient produced when the body is immersed in water, drawing hydration from the outer skin layers.” Another study documented several dermatological problems related to prolonged or repetitive water immersion, including skin denuding of the protective sebum coat[15]. The protective barrier function of the skin against ROS has been identified previously[16].

The experimental documentation presented in this manuscript supports the view that H2O2 fuels aging, inflammation, cancer metabolism, and metastasis[17] . Furthermore, the present observations provide a basis for testing the hypothesis that ROS reactions are associated with cancerogenesis[18]. We demonstrated that in hair follicles, compromised sebum/dermal sheath layers and uncompromised shaft/skin junction allow H2O2 penetration, resulting in repetitive ROS reactions and possible initiation of diseases. This could include melanoma.

Addendum

The data presented in this manuscript also supports that in fresh or seawater, the penetration of ROS into the submerged hairs occurs at the hair shaft/skin interface, as well as through the injured external structures. The risk for “swimmers melanoma” could be explained as follows: “The formation of hydrogen peroxide results principally from the UV portion of sunlight exciting humic substances in the water and thereby leads to the formation of superoxide ion, which reacts with itself to form H2O2. Because this production is limited to the depth of UV light penetration, its vertical distribution provides a sensitive tracer for mixing processes”[19].

Factor affecting the formation of H2O2 in fresh waters

DOM * UV Excitation ** O2 – *** H2O2 ****

* DOM = Dissolved Organic Matter

** UV Excitation = UV portion of sunlight (limited to depth of UV in body of water)

*** O2 - = UV portion leads to formation of superoxide ion, which reacts with itself to form H2O2. [20,21]

**** H2O2 = Vertical distribution of Hydrogen Peroxide molecules now in body of water.

Conflict of Interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

Financial Support: Self-funded.

References

1. Pitocco, D., Zaccardi, F., Di Stasio, E. et al. “Oxidative stress, nitric oxide, and diabetes. (2010) Rev Diabet Stud 7(1): 15-25.

2. Yamashiro, N., Uchida, S., Satoh, Y., et al. Determination of Hydrogen Peroxide in Water by Chemiluminescence Detection, (I). (2004) J Nuclear Sci Tech 41(9): 890-897.

3. Coble, P.G. Characterization of marine and terrestrial DOM in seawater using excitation-emission matrix spectroscopy. (1996) Marine Chem 51(4): 325-346.

4. Huang, H.H., Lu, M.C., Chen, J.N. et al. Catalytic decomposition of hydrogen peroxide and 4-chlorophenol in the presence of modified activated carbons. (2003) Chemosphere 51(9): 935-943.

5. Schneider, M.R., Schmidt-Ullrich, R., Paus, R. The Hair Follicle asa Dynamic Miniorgan. (2009) Curr Biol 19(3): R132-R142

6. Williams, R., Philpott, M.P., Kealey, T. Metabolism of freshly isolated human hair follicles capable of hair elongation: a glutaminolytic, aerobic glycolytic tissue. (1993) J Invest Dermatol 100(6): 834-840.

7. Rutala, W.A., Weber, D.J. Disinfectants used for environmental disinfection and new room decontamination technology. (2013) Am J Infect Control 41(5): S36-S41

8. Truesdale, G.A. The solubility of oxygen in pure water and sea water. (1955) J Chem Tech Biotechnol 5(2): 53-62

9. Ming, G., Zhenhao, D. Prediction of oxygen solubility in pure water and brines up to high temperatures and pressures. (2010) Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 74(19): 5631–5640.

10. James, P.A., James, E.A. Overcoming Limitations of Vaporized Hydrogen Peroxide. (2013) Pharmaceutical Technology 37(9).

Pubmed||Crossref||Others

11. Ralph, M.T. Oxidative 389 Stress in Ageing of Hair. (2009) Int J Trichology 1(1): 6-14.

12. Seiberg, M. Age-induced hair greying - the multiple effects of oxidative stress. (2013) Int J Cosmet Sci 35(6): 532-538.

13. Akar, A., Arca, E., Erbil, H., et al. Antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation in the scalp of patients with alopecia areata. (2002) J Dermatol Sci 29(2): 85-90.

14. Nelemans, P.J., Rampen, F.H., Groenendal, H., et al. Swimming and the risk of cutaneous melanoma. (1994) Melanoma Res 4(5): 281-286.

15. Rodney, S.W., Geoffrey, C.B., Amy, H.P., et al. Special skin symptoms seen in swimmers. (2000) J American Academy of Dermatol 43(2): 299-305.

16. Rinnerthaler, M., Bischof, J., Streubel, M.K., et al. Oxidative Stress in Aging Human Skin. (2015) Biomolecules 5(2): 545-589.

17. Lisanti, M.P., Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E., Lin, Z., et al. Hydrogen peroxide fuels aging, inflammation, cancer metabolism and metastasis. (2011) Cell Cycle 10(15): 2440-2449.

18. Embi, A.A. Endogenous electromagnetic forces emissions during cell respiration as additional factor in cancer origin. (2016) Cancer Cell Int 16: 60.

19. William, J.C., Shao, C., Lean, D.R., et al. Factors Affecting the Distribution of H2O2 in Surface Waters. (1994) Advances in Chemistry 237(12): 391–422.

20. Nakamura, Y., Ohtaki, S., Makino, R., et al. Superoxide anion is the initial product in the hydrogen peroxide formation catalyzed by NADPH oxidase in porcine thyroid plasma membrane. (1989) J Biol Chem 264(9): 4759-4761.

21. Nauseef, W.M. Detection of superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide production by cellular NADPH oxidases. (2014) Biochim Biophys Acta 1840(2): 757-767.