Weight Loss and Improvement of Body Composition in a Group of Women Using Food Supplements Along With Hypocaloric Diet

Magdalena Rafecas11, Laura-Isabel Arranz1*, Mireia GarcÃa2, Jonathan Hernández2, Miguel-Ãngel Canela3

Affiliation

- 1Department of Nutrition and Food Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Barcelona, Spain

- 2Dietitian Nutritionist of DIECA group, (DIECA is the acronym in Spanish of Diet, Exercise, Food supplements)

- 3Department of Managerial Decision Sciences, IESE Business School, Barcelona, Spain

Corresponding Author

Laura Isabel Arranz, Department of Nutrition and Food Science, University of Barcelona, Faculty of Pharmacy, Barcelona 08028, Spain, Tel: 934 024 527-934 024 508; Fax: 934 035 931; E-mail: d lauraarranz@ub.edu

Citation

Arranz, L.I., et al. Weight Loss and Improvement of Body Composition in a Group of Women Using Food Supplements Along With Hypocaloric Diet (2015) Int J Food Nutr Sci 2(2): 155-159.

Copy rights

© 2015 Arranz, L.I. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Overweight; Body Mass Index; Anthropometric Measures; Food Supplements; Hunger; Hypocaloric Diet

Abstract

Obesity and overweight are increasing health problems characterised as a higher than normal body weight due to an abnormal increase in body fat. Body weight adequacy is categorized by using body mass index (BMI) nevertheless it doesn’t give information about body composition. Also fat mass (FM), waist circumference (Wci), hip circumference (Hci) and waist to hip ratio or waist to height ratio, are relevant. Ideally, these parameters should be calculated initially to evaluate changes during every dietary intervention with a weight loss goal. Many patients use food supplements when they are willing to slim. The aim of this study was to assess the improvement of weight and body composition parameters through the use of food supplements intended to help weight control along with hypocaloric diet. Seventy- eight women who wanted to lose weight were recruited in the program and splitted into intervention or control group (food supplement plus diet or diet alone) and were monitored for 8 weeks. Anthropometric measures (weight, height, body mass index, fat mass, waist and hip circumference) were taken. The mean age was of 36.27±7.59 and most of them were within overweight or obesity values for BMI, FM, Wci and Hci. After 8 weeks, both groups got positive results, especially with different ranges of improvement in body composition. As expected, improvements were better within the intervention group than within the controls. Some food supplements may be an aid to manage weight control and professional individualised assessment about their right use and diet is critical to succeed.

Introduction

Obesity and overweight are increasing health problems worldwide, also linked to an increased risk of diseases like type 2 diabetes, dyslipemia, hypertension, coronary heart disease, some type of cancers, osteoarthritis, and others[1]. In Spain, the prevalence of obesity in adults is around 17% and obesity plus overweight is around 54 %[2,3]. Both are characterized as a higher than normal body weight due to an abnormal increase in body fat storage. Body weight adequacy is normally categorized using body mass index (BMI), however other parameters as fat mass (FM), waist circumference (Wci), hip circumference (Hci) and waist to hip and waist to height ratios, are relevant and useful to evaluate carefully and individually the extent of the health problem. BMI is the result of dividing body weight (kg) by the height square (m²). The established categories for BMI are shown on table 1. Waist circumference is the distance around the abdomen and this measure is used to assess the degree of abdominal obesity and also cardiovascular risk. Hip circumference (Hci) is recorded on the widest part of the hips. It is considered that for a good health, waist should measure no more than 80 cm in women and 94 cm in men, and abdominal obesity exists when waist circumference is more than 88 cm in women and 102 cm in men[4], or when the waist to hip ratio is above 0.85 in women and 0.9 in men[5]. The waist to height ratio is a simple measurement for assessment of abdominal fat mass and cardiovascular risk, with considered healthy values those under 0.5[6,7]. Compared to just measuring waist circumference, waist to height ratio is equally fair for men and women and also for short and tall persons. Measuring waist to height ratio is gaining popularity in the scientific society as several studies have found that this is a more valid measurement than BMI. Ideally, body weight and body composition, with all these anthropometric parameters, should be calculated initially in order to evaluate changes during every weight loss dietaryintervention[8].

Table 1: International Classification of adult underweight, overweight and obesity according to BMI. Source: Adapted from WHO, 1995, WHO, 2000 and WHO 2004.

| Classification | BMI (Kg/m²) |

|---|---|

| Underweight | < 18.50 |

| Normal range | 18.50 - 24.99 |

| Overweight | 25.00 - 29.99 |

| Obeseclass I | 30.00 - 34.99 |

| Obeseclass II | 35.00 - 39.99 |

| Obeseclass III | ≥ 40.00 |

Another interesting aspect to take into account is the fact that changing behaviours and habits related to health are not easy. It is hard to quit smoking, to start in physical activity, and specially to change eating patterns. All are difficult challenges for anyone in spite of having a health benefit as a result[9]. When people are enrolled in a hypocaloric diet there is a risk of demotivation or even of abandoning due to the difference of expected and real results. It is often the reason why consumers who want to lose weight seek also for some aids, like food supplements, to improve the outcome or to get a faster effect. Under a sensible point of view, some food supplements could be of help but always used in the context of a balanced and calorie adjusted diet and a healthy lifestyle. Consumers can benefit from the use of these products and also from professional advice on how better using them. It is also possible that using a food supplement along with a hypocaloric diet could be positive leading to a greater adherence to treatments or programs. Moreover, epidemiologic studies have begun to show links between adiposity and behaviours such as television watching, alcohol intake, stress, and sleep deprivation because they are likely to contribute to overweight and obesity by encouraging excessive eating[10,11]. Regarding exercise, there are physiological, psychological and behavioural factors potentially involved in its relationship with appetite. People, who exercise, frequently compensate for the increase in energy expenditure via compensatory increases in hunger and food intake. However, this is not always likely to happen, and responses to exercise will vary. Understanding and characterizing this variability will help weight loss strategies to suit individual needs[12]. It seems that women are more prone to look for weight management strategies and also to use food supplements. In addition, abdominal obesity is strongly and positively associated with cardiovascular mortality and cancer mortality among women[13]. Hypocaloric diets are one of the main weight loss tools which, along with exercise, facilitate the achievement of a negative energetic balance (to eat fewer calories than wasted). However, there are other factors that influence whether a hypocaloric diet would be successful or not, for example hunger experience, monotony, slowness achieving the results and so on. These factors affect the adherence to diet and consequently completion of the treatment.

Some dietary products are formulated specifically to help in weight control by different physiological effects like improving satiety, increasing resting metabolic rate, or blocking fat and carbohydrates intestinal absorption. These products are marketed as food supplements (FS) and among their ingredients two of the most popular are chitosan, bitter orange extract, along with vitamins and minerals. All of them have demonstrated some effects which could be of help for people looking for weight loss along with diet and exercise. On the other hand it is postulated that the use of such products could enhance the whole adherence to treatment and even improve the outcome[14]. Chitosan is the N-deacetylated form of chitin that is extracted from the shells of crustaceans but also from some mushrooms. It is a polysaccharide containing copolymers of glucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine, structurally similar to cellulose, which undergoes minimal digestion and is excreted in the faeces. Some evidence suggests that positively charged chitosan polymers bind to negatively charged bile acids and therefore helps to lower cholesterol levels and also it is hypothesized that could be of help in weight loss by binding to negatively charged lipids hence reducing their gastro-intestinal uptake[15-21]. Bitter orange is also known by its scientific name Citrus aurantium. Applicable parts are the peel, flower, leaf, and fruit, including numerous active constituents with different effects. The fruit and peel are rich in flavonoids but also contain the adrenergic agonistssynephrine and octopamine, which might have a role in fat cell lipolysis. This is the reason why this ingredient is included in some weight loss food supplements[22-26].Vitamins and minerals are generally added in food supplements addressed for weight control due to their role supporting metabolic processes[27]. Food supplements based on these ingredients could be of help for people following hypocaloric diet in order to have better results on weight loss or maintenance, more adhesion to treatment. Moreover, people seek these products looking for an easier solution to their weight problems, not always completely conscious that they could be of help although a change in dietary habits and life-style is also needed. Health professional role is of a great value during a weight loss process, giving advice on how to use products and also on how to follow hypocaloric diet, leading to higher success rates.

Methods

In order to recruit participants, we organized an open and free weight loss program for people with excess body weight who wanted to slim some kilograms. The inclusion criteria established for the study were: healthy women between 20 and 45 years old, with overweight (based on self-perception). We excluded from the participation men, and people with chronic diseases or who were under chronic medical treatments. The call, offering free participation and explaining conditions to be on, was made by Internet, targeting people living in Catalonia as the study was going to be made in Barcelona. The call lasted active for some days until enough participants were recruited.

Selected participants were asked to answer a questionnaire about their age, their weight and height, their life history with slimming diets, weight they wanted to lose and hunger experience. We also took measures of weight, bodymass index, fat mass percentage and waist and hip circumference. Weight, BMI, and FM percentage were taken with an OMRON BF511 body composition analyzer. Waist and hip circumference were taken with a common tape and measured in centimeters (cm). The waist measure was made with person with a normal breath, starting at the top of the hip bone, bringing a tape measure all the way around, and leveling with the belly button, making sure it was not too tight and that it was straight. Similarly, hip was measured at its widest portion of the buttocks. Participant’s wererandomly assigned to two groups, control or intervention group. Those included in the control group were assessed to follow the hypocaloric diet (Diet group) and those included in the intervention group were assessed to take food supplements along with hypocaloric diet (Diet + FS).

During 8 weeks all participants within both groups followed one specific hypocaloric diet based on the Mediterranean model and with a mean caloric content of 1500 Kcal. Women within the intervention group used also two different food supplements, one of them during the first two weeks and the other one during the following 6 weeks. The first product had bitter orange in its composition along with other ingredients intended to help metabolism to waste calories. The second one was based on chitosan, Chitoglucan® and zinc. These food supplements were Lipograsil® 15 dias Choque and Lipograsil® Gestor de Grasas respectively and were provided by Zambon, S.A.U.

All participants were visited four times (first day, and at weeks 2, 4 and 8). Anthropometric measurements (weight, BMI, percentage of body fat, waist and hip circumference) were taken in each visit and also dietetic questionnaires were used to check diet compliance. Dietitians visiting them were instructed to standardize recommendation criteria and methodology. Measures from first and final visit at week 8 were compared. We compared changes for each anthropometric parameter within each group using a paired t test, and also compared results between intervention and control group using a 2-sample t test. Mean values were calculated with standard deviation (SD).

Results

Around 200 women responded to the call launched over the Internet, and finally 78 women agreed to participate, attended to our first visit and were enrolled in this weight loss program for 8 weeks. All of them were living around the city of Barcelona (Spain) the most of them were Spanish but some of them were originally from South-American.

The mean age within the whole group of participants was of 36.27 ± 7.59 years, within Diet group was of 38.18 ± 8.24 and within Diet + FS group was of 35.52 ± 7.25. In both groups most of our participants were in perimenopause period, and most of them referred body changes typical of this phase. Weight they wanted to lose was of 9.19 ± 7.03 kg with a wide range among participants from 3 to 30 kilograms. The mean value of initial BMI was 28.53 ± 4.91, corresponding to a grade II overweight range. However, 20 were in normal BMI values, 33 within overweight BMI range, and 25 showed BMI values within obesity range. The mean value for body FM percentage was of 41.71 ± 6.42 lying within the category of obesity, according to reference criteria[6]. In fact, most of participants had, at the beginning of the program, a FM percentage higher to the considered as normal or healthy, even those who had normal BMI values. Only 1 participant had an initial FM percentage equal to or below 27, which would be the desirable value for women at this age.

Among all the participants, Wci and Hci values were generally high, with a mean value of 92.31 ± 11.17 and 109.21 ± 8.74 respectively. For Wci most of our participants were at obesity values (see Table 2) and mean values were in general high. Moreover, 43.6% of the participating women had a waist to hip ratio higher 0.85, indicating that almost one third of them had abdominal obesity. And about the waist circumference to height ratio 46 participants had a value over 0.5 indicating also cardiovascular risk.

Table 2: Initial anthropometric values and other characteristics within Diet and Diet + FS groups. Mean values (X ± SD) for: age (years), wanted weight to lose, body mass index (BMI), percentage of fat mass (%FM), waist circumference (Wci), hip circumference (Hci).

| Diet (n = 22) | Diet + FS (n = 56) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 38.18 ± 8.24 | 35.52 ± 7.25 |

| Mean wanted weight to lose (kg) | 10.27 ± 7.62 | 8.77 ± 6.81 |

| BMI | 28.56 ± 4.89 | 28.51 ± 4.97 |

| %FM | 42.65 ± 4.79 | 40.94 ± 6.99 |

| Wci | 93.98 ± 12.21 | 90.25 ± 10.77 |

| Hci | 108.7 ± 8.87 | 108.48 ± 8.77 |

At the beginning of the study, anthropometric measures within Diet and Diet + FS groups were very similar, with no significant differences neither for BMI, FM percentage, Wci, Hci values, nor for body weight they wanted to lose (see Table 3).

Table 3: Description of waist circumference (Wci) at the beginning of the study. Number of participants within normal, overweight and obesity Wci values, and mean Wci value (X ± SD) within each group.

| Wci < 80cm (normal) | Wci 80- 88cm (overweight) | Wci > 88cm (obesity) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants (total n = 77) | 7 | 21 | 46 |

| Mean Wci (cm) | 75.9 ± 2.9 | 84 ± 2.4 | 99.1 ± 8.4 |

After the 8 weeks study there was, in general, an improvement on measured parameters (weight, BMI, FM, Wci and Hci), although these results were better within the intervention group (Diet + FS) than in the control (Diet), due to the synergic effect of the food supplement along with hypocaloric diet.

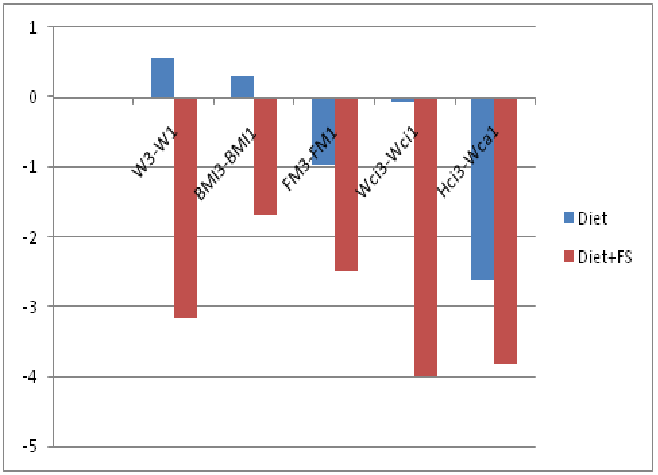

Among the Diet group (n = 22) there was no weight loss after 8 weeks, even there was a slightly increase of 0.57 kg, and consequently BMI also increased in 0.31 points. Fat mass percentage decreased a mean of 0.96 points, waist circumference decreases a mean of 0.07, and the reduction of hip circumference was consistently greater with a mean decrease of 2.61 points. Among the Diet + FS group (n = 56) the mean weight loss after 8 weeks was of 3.17 kg, BMI diminished 1.68 points and FM percentage decreased a mean of 2.49 points. Waist and hip circumferences decreased a mean of 4 cm and 3.82 cm respectively (Figure 1, Table 4).

Table 4: Total results. Difference measurments between first day and 8 week (W3-W1), body mass index (BMI3-BMI1), fat mass percentage (FM3-FM1), waist circumference (Wci3-Wci1) and hip circumference (Hci3-Hci1)

| W3-W1 | BMI3-BMI1 | FM3-FM1 | Wic3-Wic1 | Hci3-Hic1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diet | 0,57 | 0,31 | -0,96 | -0,07 | -2,61 |

| Diet + FS | -3,17 | -1,68 | -2,49 | -4 | -3,82 |

Figure 1: Total results. Difference measurments between first day and 8 week (W3-W1), body mass index (BMI3-BMI1), fat mass percentage (FM3-FM1), waist circumference (Wci3-Wci1) and hip circumference (Hci3-Hci1).

Intervention group got better outcome, therefore, as expected, these food supplements were of help when used along with hypocaloric diet. All positive outcomes, which are reduction in all parameters, within Diet + FS group, were statistically significant (p < 0.05). Products were well tolerated with only five participants who complained of constipation during the treatment. We assume the limitation of this study is sample size, as a whole, and also the difference between control group and intervention groups.

Conclusion

Weight management is a current concern within Spanish population, especially within women, probably very similar to other countries. Women in perimenopause phase are more prone to become overweight and also to look for some products as an aid. Food supplements are often used to manage body weight, sometimes alone or sometimes along with diet and exercise, which is the ideal situation. Body weight but also other anthropometric parameters must be considered when assessing people in a slimming program. Within participants included in this study anthropometric parameters were higher than expected, frequently within overweight and even obesity values. Most of the women who participated in this program were within the overweight or obesity BMI range. FM values corresponded mainly to overweight and also to obesity, even for those women who had normal BMI values. Waist circumference was in general higher than normal. Waist to hip ratio and also waist to height ratio indicated around half of these participants, or more, had abdominal obesity and cardiovascular risk.

During the 8 weeks program, both groups got positive results, especially in fat mass, and waist and hip circumferences reduction. However, as expected, improvements were better in the intervention group (Diet + FS) than in the control group (Diet), probably due to the synergy of using these food supplements along with a hypocaloric diet.

In summary, people who look for weight loss could be either in slight overweight or in obesity parameters, and also have cardiovascular risk. The varied characteristics should also be taken into account by health professionals reinforcing the need to tackle overweight and obesity in an individualized manner, with information about dietary background, lifestyle and anthropometric measures. The results of this modest study show that food supplements addressed to weight management may be useful, especially when used along with a hypocaloric diet, and even more when used with personal assessment which seems to be also a key motivational factor to achieve proper outcomes and to use adequately these products. More studies will be needed to assess the usefulness of specific food supplements promoting weight loss along with diet and exercise.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the financial support of Zambon S.A.U. which made possible the study by providing with the necessary food supplements (Lipograsil® products).

Conflict of interest

LIA is associate professor at University of Barcelona but also holds a position as medical affairs at Zambon, S.A.U.

References

- 1. Global Health Observatory (GHO) Risk factors. Overweight Geneva. (c2014)World Health Organization (WHO).

- 2. Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. (2012) ENSENational Health Survey of Spain. Madrid.

- 3. Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. (2011) ENIDE National Survey of Dietary Intake of the Spanish population. Madrid.

- 4. Lean, M.E., Han, T.S., Morrison, C.E. Waist circumference as a measure for indicating the need for weight management.(1995) BMJ (15)311: 158-161.

- 5. Waist circumference and waist–hip ratio. (2008) report of a WHO expert consultation, Geneva8-11.

- 6. Lee, C.M., Huxley, R.R., Wildman, R.P., et al. Indices of abdominal obesity are better discriminators of cardiovascular risk factors than BMI: a meta-analysis. (2008) J ClinEpidemiol61(7): 646-653.

- 7. Browning, L.M., Hsieh, S.D., Ashwell, M. A systematic review of waist-to-height ratio as a screening tool for the prediction of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: 0•5 could be a suitable global boundary value. (2010) Nutr Res Rev 23(2): 247-269

- 8. Rubio, M.A., Salas-Salvadó, J., Barbany, M.,et al. Consenso SEEDO 2007 para la evaluación del sobrepeso y la obesidad y el establecimiento de criterios de intervenciónterapéutica. (2007) Rev Esp Obes: 7- 48

- 9. Zimmerman, G.L, Olsen, C.G., Bosworth,M.F.,et al. ‘Stages of change’ approach to helping patients change behavior. (2000) Am Fam Physician 61(5): 1409- 1416.

- 10. Chapman, C.D., Benedict, C., Brooks,S.J., et al. Lifestyle determinants of the drive to eat: a meta-analysis. (2012) Am J Clin Nutr 96(3): 492-497.

- 11. Maniam, J., Morris, M.J. The link between stress and feeding behaviour. (2012) Neuropharmacology 63(1): 97- 110.

- 12. King, N.A., Horner, K., Hills, A.P., et al. Exercise, appetite and weight management: understanding the compensatory responses in eating behaviour and how they contribute to variability in exercise-induced weight loss. (2012) Br J Sports Med 46(5): 315-322.

- 13. Zhang, C., Rexrode, K.M., van Dam, R.M., et al. Abdominal obesity and the risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality: sixteen years of follow-up in US women. (2008) Circulation 117(13): 1658- 1667.

- 14. Rafecas, M., Arranz, L.I., García, M.,et al. Improvement of Weight and body composition in a group of women through a weight management program using food supplements with or without a hypocaloric Diet. (2014) JPANS 4: 238-245.

- 15. Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to chitosan and reduction in body weight (ID 679, 1499), maintenance of normal blood LDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 4663), reduction of intestinal transit time (ID 4664) and reduction of inflammation (ID 1985) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 (2011) EFSA Journal 9(6): 2214.

- 16. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. (2013) Chitosan Monograph. Therapeutic Research Center.

- 17. Alt Med Dex. (2012) Micromedex

- 18. Health Canada. (2013) Chitosan Monograph.

- 19. Jull, A.B., Ni Mhurchu, C., Bennett, D.A., et al. Chitosan for overweight or obesity (Review). (2008) Cochrane Database Syst Rev 16(3): CD003892

- 20. Cornelli, U., Belcaro, G., Cesarone, M.R., et al. Use of polyglucosamine and physical activity to reduce body weight and dyslipidemia in moderately overweight subjects. (2008) Minerva Cardioangiol 56(5): 71- 78.

- 21. Walsh, A.M., Sweeney, T., Bahar, B., et al. Multi-functional roles of chitosan as a potential protective agent against obesity. (2013) PLoS One 8(1): e53828.

- 22. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. (2014) Bitter Orange Monograph.

- 23. Natural Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). (2012) Bitter Orange Monograph. National Institute of Health.

- 24. Efsa scientific cooperation (ESCO) report. Advice on the EFSA guidance document for the safety assessment of botanicals and botanical preparations intended for use as food supplements, based on real case studies. ESCO working group on botanicals and botanical preparations. (2009) EFSA Journal l7(9): 280.

- 25. Stohs, S.J., Preuss, H.G., Shara, M. A review of the human clinical studies involving Citrus aurantium (bitter orange) extract and its primary protoalkaloid p-synephrine. (2012) Int J Med Sci 9(7): 527- 538.

- 26. Bent, S., Padula,A., Neuhaus, J. Safety and efficacy of citrus aurantium for weight loss. (2004) Am J Cardiol 94(10): 1359- 1361.

- 27. Huskisson, E., Maggini, S., Ruf, M. The role of vitamins and minerals in energy metabolism and well-being. (2007) J Int Med Res 35(3): 277- 289.